Exposed: Latino farmworkers risk their health working under threat of pesticide exposure

The story was originally published in Univision with support from our 2022 National Fellowship.

José Soria refused to keep working on a sweet potato field in North Carolina. In the span of hours, a rash on the left side of his abdomen had turned into painful blisters that covered his skin in pus. His boss gave him an ointment and attributed the sores to some ivy. She warned that if he decided to go to the doctor he would have to cover the cost of the visit himself. The Mexican worker decided to seek out care anyway. He feared more for his health than for the possibility of suffering retaliation from his employer, even though they were sponsoring his temporary work visa.

On August 2, 2020, at the height of the pandemic, he was referred to UNC Health in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. According to a report by the doctors who evaluated him, Soria had second-degree burns caused by the chemical paraquat, one of the most used herbicides in the United States. It’s classified as “highly toxic” by the EPA, the federal environmental protection agency in charge of regulating the use of pesticides.

Paraquat was banned in more than 30 countries, including large agricultural producers such as China (since 2017) and the European Union (since 2007); it was also banned in Switzerland (since 1989), where one of its largest manufacturers is based.

Soria recalled that a week earlier, a tractor had suddenly sprayed a pesticide—no one told him which—on the sweet potato crop where he and seven other farmers were working. Just then, the wind carried a chemical smell and he felt his face burning.

The farmworker also remembered that a few days after that incident, on July 30, he spent the day pulling weeds where the pesticide had been sprayed. His boss asked him to put the weeds in a ditch. He carried the pile of weeds on the left side of his abdomen—the same place now covered in sores.

Federica Narancio/Univision

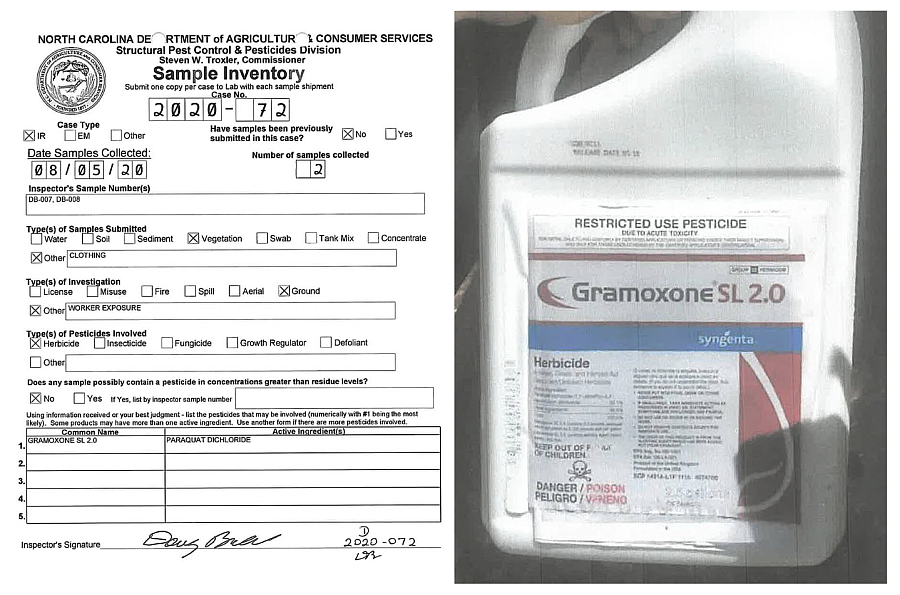

An investigation conducted by the North Carolina Department of Agriculture concluded that the applicator had sprayed the herbicide Gramoxone SL 2.0; its active ingredient is paraquat. The report includes a photo of the label with the name of the pesticide and the Swiss firm that markets it in the United States.

An inspector was able to verify that it was paraquat through a review of the chemicals applied by Soria's boss, as well as the results of laboratory tests on the farmworker's clothing and a sample of the weeds.

Images taken from the North Carolina Department of Agriculture’s investigation report. “Poison,” it reads in red.

The state agency declared that the herbicide was used “in a faulty, careless, or negligent manner” that did not comply with the label’s specifications. “Gramoxone was not approved for use on sweet potatoes,” wrote Patrick Jones, director of the Structural Pest Control and Pesticides Division of the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

The company was fined $800.

Soria underwent surgery to reconstruct the burned skin and was given a chemotherapy drug. He was out of work for two months and needed psychological support.

“I was desperate, because what could I do without money? I wasn't sleeping well because I was thinking about a million things. Every night it struck at 2 or 3… I had anxiety, I was depressed.”

The first image shows a worker’s burn and was taken from the investigation report of the North Carolina Department of Agriculture; the second and third are part of José Soria's medical history, requested from UNC Health with the patient's authorization

Over two years we spoke to more than 30 workers to understand how pesticide exposure has impacted their daily lives. Like Soria, all of these workers have been sprayed in the course of their daily work with unknown chemicals from tractors, airplanes or by those fumigating on foot. They’ve also come into contact with pesticide residue by touching fruits that had recently been sprayed. These workers are rarely informed of the dangers they face.

We also interviewed and consulted at least 15 experts, academics and activists from Michigan, North Carolina, Florida, Texas, and Illinois.

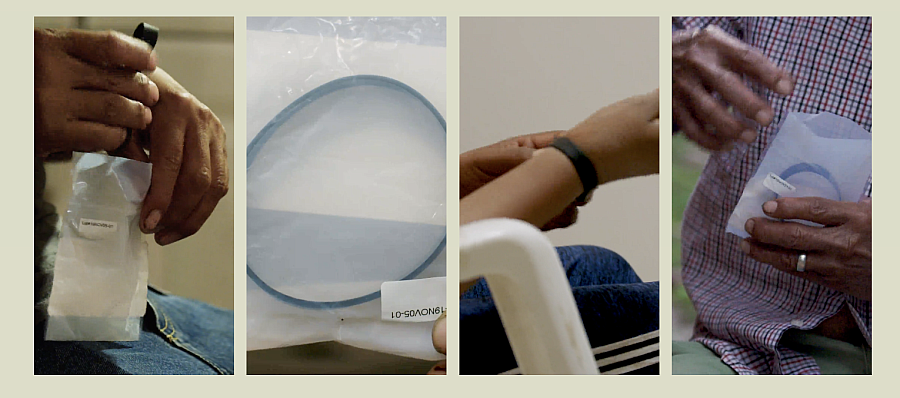

With their help, we came up with a tool to investigate pesticide exposure: special silicone wristbands that are able to detect dozens of pesticides. We used them on farmworkers in three states.

This farmworker holds a temporary H-2A visa to work in tobacco fields in North Carolina.

Federica Narancio/Univision

This report shows some of the consequences of immediate and prolonged exposure to these chemicals: from skin rashes to serious illnesses, and even birth defects.

These cases are just a small sample of a problem that few consumers know much about. They show how the system that should protect farmworkers frequently fails them.

Pesticides are substances or combinations of substances used on crops to control pests and weeds. Although regulations exist in the United States to reduce consumer risk, some fruits and vegetables we eat may contain residues that are potentially risky to human health, as shown in an analysis by Consumer Reports, a nonprofit organization dedicated to evaluating the goods and services that reach consumers.

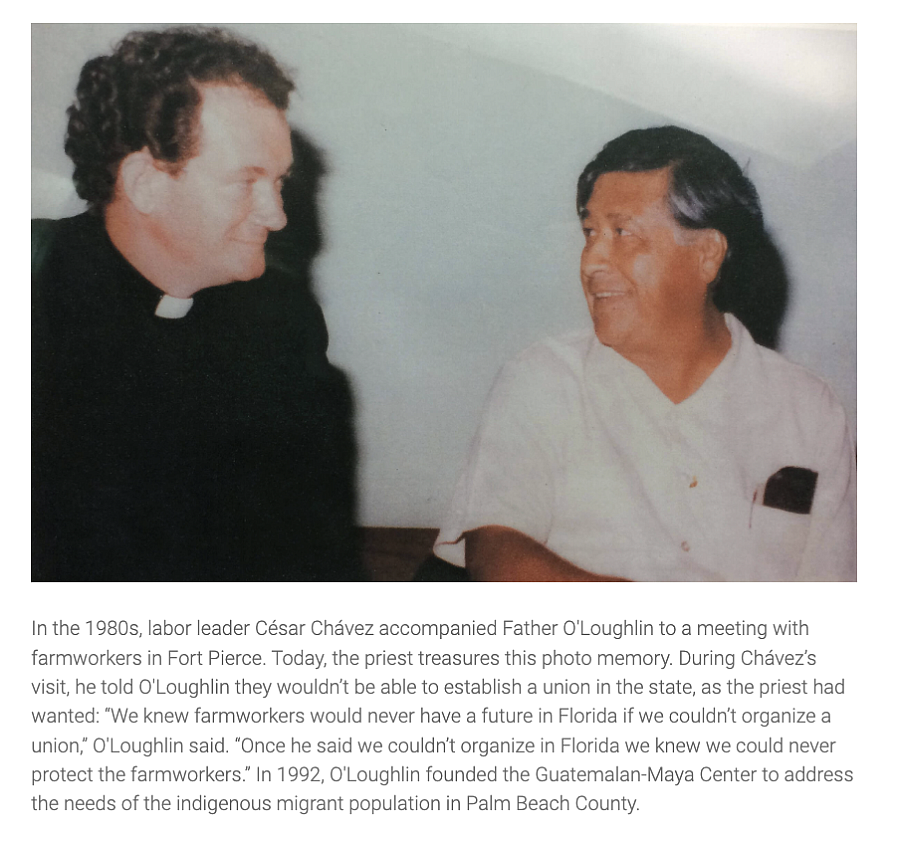

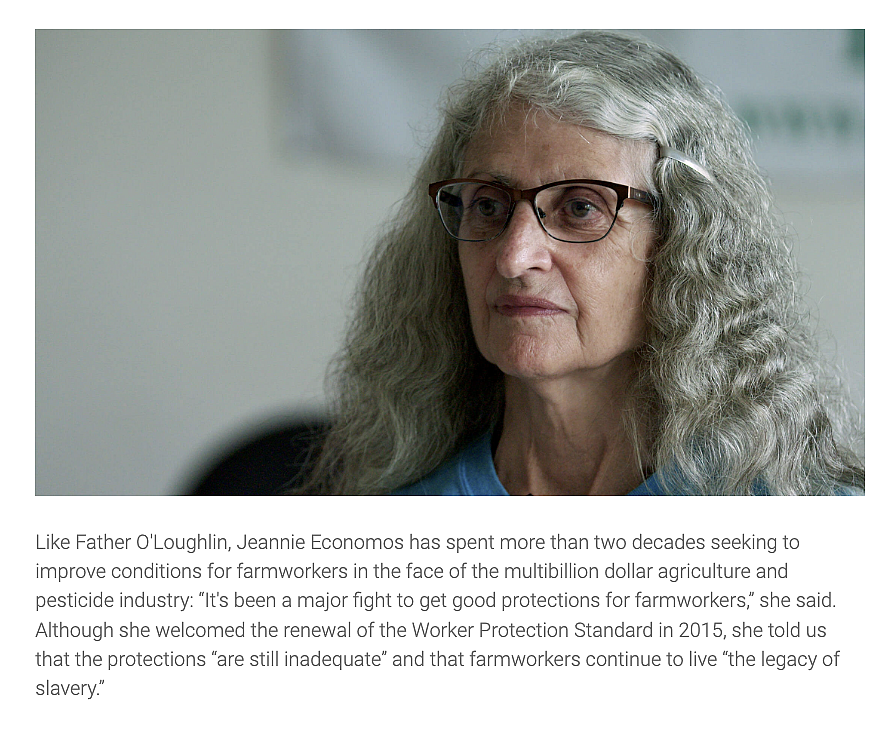

“Farmworkers are exposed to pesticides all the time, and yet they don't get the protections they need,” said Jeannie Economos, an activist who has spent 17 years coordinating a project at the Farmworker Association of Florida to teach workers how to protect themselves from pesticides.

She and other activists we spoke to have heard for years from migrants who’ve been sprayed—either directly or because wind carries pesticides from nearby farms—while picking or clearing weeds in fields and nurseries. They also may come into contact with pesticides after stepping onto a field too shortly after it was sprayed.

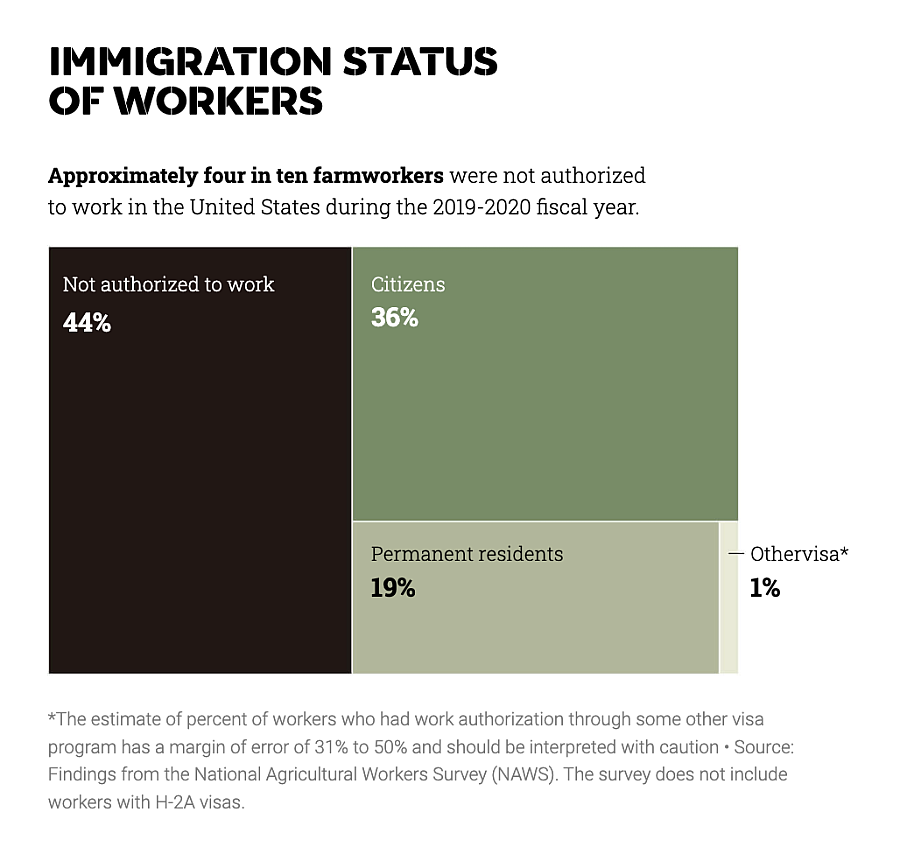

Not all cases end up as investigations. Workers—mostly undocumented and with temporary visas dependent on their employer—prefer to remain silent for fear of reprisal or discrimination. They distrust a system that rarely punishes bosses who break the rules. And when a long time has passed since an incident occurred, it’s almost impossible to collect evidence.

They often choose not to go to the doctor because they don't have transportation or insurance, or because they don't want to lose work hours and pay. That also means they don’t obtain a health professional's report to be used as evidence.

Soria is one of the few workers we met who refused to stay silent. With the help of a local union, he sought workers' compensation and won: the company’s insurance had to pay him part of his salary for the weeks he was out of work, in addition to his medical expenses and compensation of around $1,000.

Justin Flores, the union organizer who helped Soria present his case, told us it was the “worst pesticide exposure case” he’s seen in 15 years of organizing farmworkers. He felt the Department of Agriculture “really wasn't aggressively pursuing what were very serious injuries,” adding that agencies responsible for investigating incidents of pesticide exposure often operate like “a good ol’ boy system where they … do the bare minimum” on behalf of those impacted.

Flores wonders whether more severe punishments would guarantee that no other migrants are affected by the faulty application of pesticides: “The system shows that the value of farmworkers’ health is not respected by anybody—not by the workers' compensation system, not by the Department of Agriculture.”

In Florida, farmworkers report feeling belittled: “Farmworkers have told us that employers care more about their crops than they do about the farmworkers themselves,” Economos said. “They care more about their bottom line than about the lives of the farmworkers.”

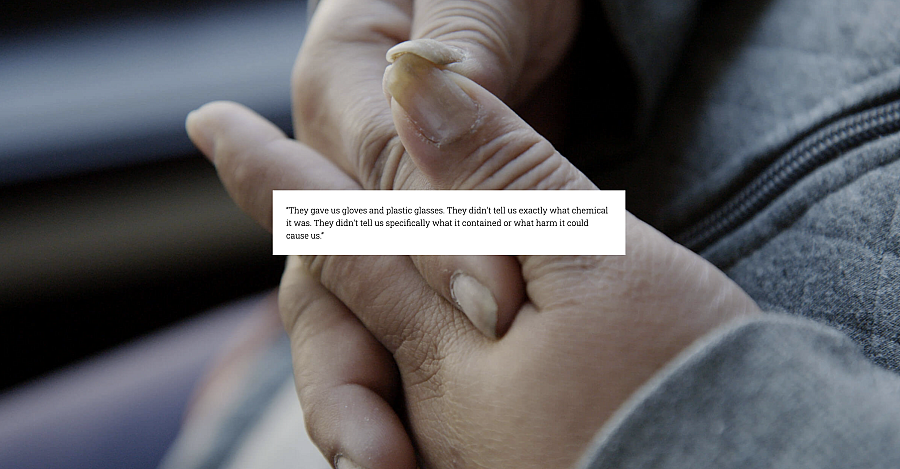

Like "María," a 40-year-old Guatemalan who requested we not use her real name for fear of retaliation. She told us that nearly every day, she breathes the chemicals sprayed on the plants at the nursery where she’s been working for almost 14 years in Florida. No one has told her exactly what’s being applied or how to protect herself, even though she can smell and feel the chemicals. She suffers from frequent headaches, rashes and coughs.

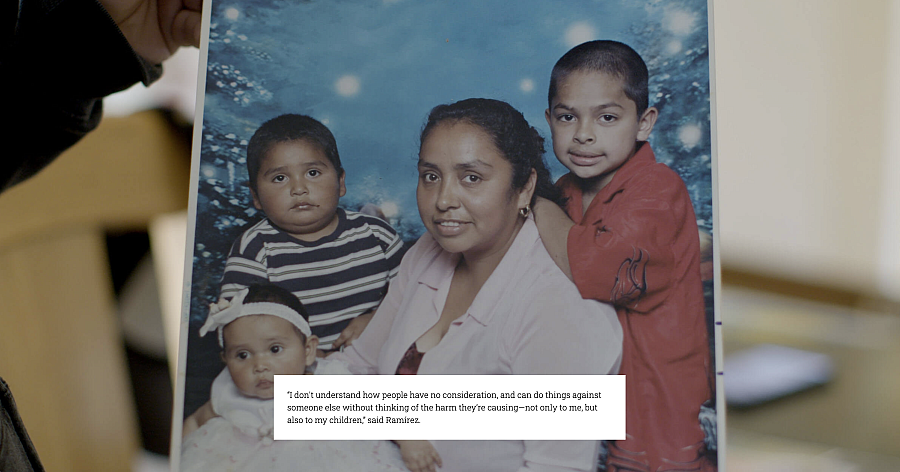

In Michigan, Hortencia Ramírez, a Mexican woman who has been working in fields in the U.S. for nearly 30 years, was accidentally sprayed with an insecticide and a fungicide by a plane in August 2014 while working in a blueberry field.

The following videos were recorded by fellow farmworkers on August 7, the day they were sprayed:

According to case documents, some of her co-workers immediately experienced difficulty breathing, headaches, nausea, watery eyes and throat irritation. She fainted and suffered from headaches and vertigo for months after.

We wanted to understand the types of chemicals present in agricultural areas where workers spend their days—or may even live. On the recommendation of researchers who study pesticide exposure, we used a tool normally employed in scientific studies: silicone wristbands capable of detecting up to 75 pesticides. These wristbands have never before been used on farmworkers as a reporting tool.

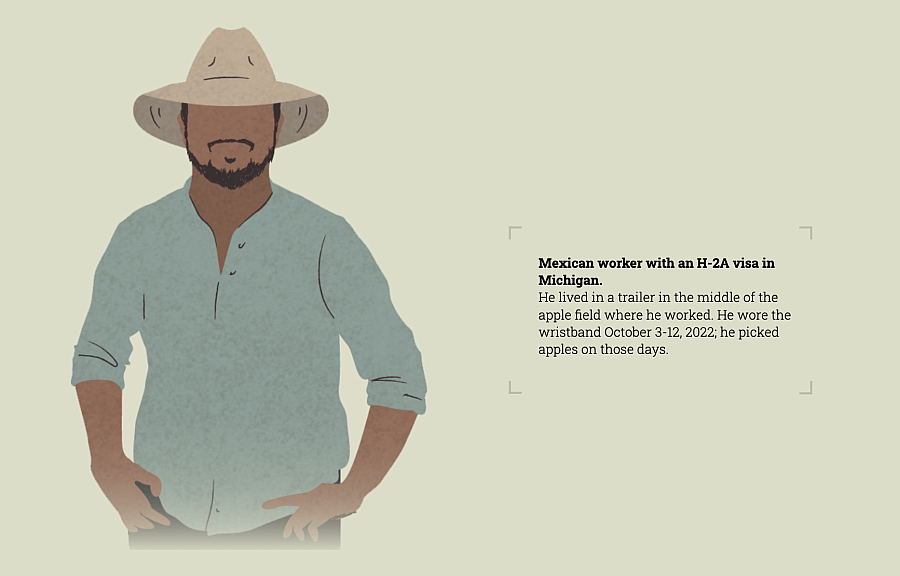

We placed 10 of these wristbands on farmworkers in Florida, Michigan and North Carolina. Four of the workers had H-2A temporary work visas—dependent on an employer—and the rest were undocumented.

They wore the wristbands for at least five days as they picked apples, pumpkins, blueberries and other crops, or worked in tobacco fields or near ornamental plants.

Five of the farmworkers lived in trailers on agricultural land, in some cases in the same fields where they worked.

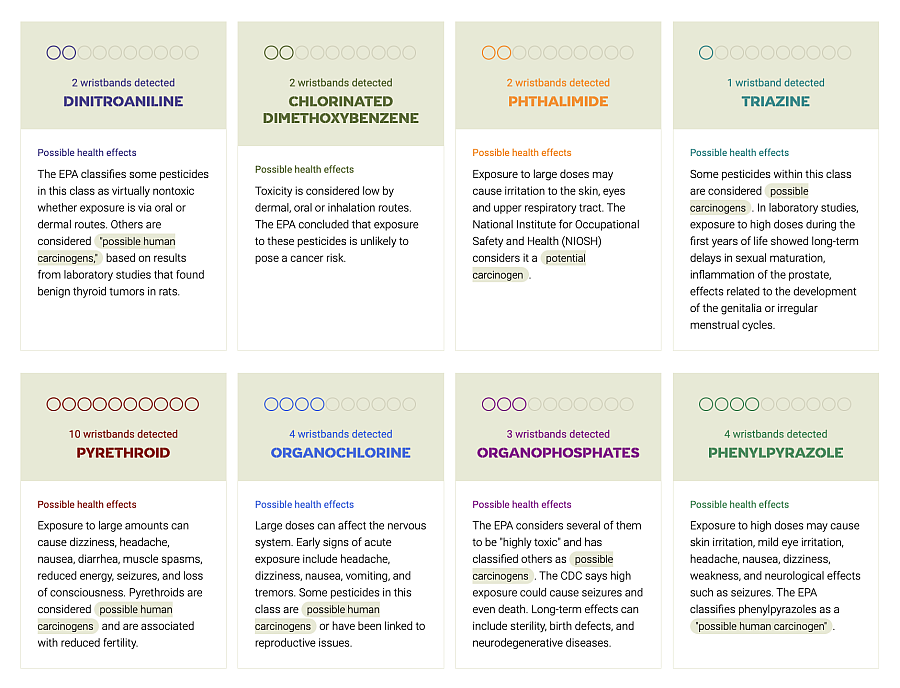

All of the workers’ wristbands showed the presence of pesticides, at levels similar to those reported in scientific studies on farmworker populations.

Three of them showed exposure to organophosphates, a class of pesticides linked to an increased risk of cancer, reproductive problems and neurological diseases.

Two wristbands detected chlorpyrifos in August and October 2022. At that time, it was banned for use on food crops.

Extensive scientific research linked it to neurological harm in children.

Four workers were exposed to pesticides classified as organochlorines. They persist in the environment and accumulate in body fat.

The wristbands detected two organochlorines banned decades earlier: 4,4'DDE and trans-nonachlor.

All workers were exposed to pyrethroids. These insecticides are increasingly used in agriculture. They are associated with adverse effects on the cardiovascular and nervous systems and can cause endocrine disruption. They are classified by the EPA as possible carcinogens.

This worker reported the highest exposure in our sample. His wristband detected seven of the most toxic pesticides, including two organochlorines and one organophosphate.

The table below shows that the wristbands detected 18 pesticides. We organize them according to their generic class: organochlorines, pyrethroids, phthalimide, organophosphates, phenylpyrazoles, triazines and dinitroaniline.

With help from Linda Forst, a physician and professor of occupational and environmental health at the University of Illinois Chicago, we describe the acute and chronic effects that these chemicals can cause, based on tests done on animals.

Our results are just a snapshot of the pesticides these 10 farmworkers were exposed to in their environments, potentially through their skin and residually in small quantities. The wristbands aren’t able to detect exact quantities.

“What you found is that everyone in your sample of ten farmworkers is exposed to multiple pesticides. This is consistent with other research that we and others have conducted that shows that all agricultural workers are exposed to a wide range of pesticides consistently across the agricultural seasons,” said Thomas Arcury, a medical anthropologist who has conducted extensive research on rural populations in North Carolina and who helped analyze the results.

The type of pesticide exposure that’s most common among farmers involves low daily doses that may be consistent over a long time. That’s what the wristbands detected as well.

“The long-term health effects of such prolonged, low-dose exposure can be devastating, including increased risk of cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, and reproductive health problems,” explained Arcury, a professor emeritus at the Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

Linda Forst, known for her research on farmworkers and public health, told us that most of the pesticides detected are accepted by the EPA for use in agriculture, according to their labels.

But two of the wristbands detected pesticides banned in the United States in the 70s and 80s after they were linked to reproductive problems and cancer in humans: 4,4'DDE and trans-nonachlor.

That doesn’t mean they’re being used now, she said. They appear in the analysis because the chemicals “persist” for years in the environment.

Those same wristbands also detected chlorpyrifos, an organophosphate that can affect the nervous system. The EPA banned its application on food crops as of February 2022, pointing to its potential to cause permanent brain damage in children, as had been exposed in scientific studies. But a federal appeals court threw out the agency's complete ban in November 2023.

It’s difficult to determine where the two agricultural workers were exposed to chlorpyrifos, said medical anthropologist Sara Quandt: “It could have been applied to the crop they were working in, but it could also have been detected in their homes, in their vehicles, anywhere else while they were wearing the wristbands,” says the professor emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Medicine.

In a study published by Quandt and Arcury in 2021, in which they used silicone wristbands on 73 Latino children, they found the insecticide both in minors who lived in the countryside and in others who did not reside in agricultural environments.

Chlorpyrifos was banned for use in U.S. homes more than two decades ago. But it can remain for years in an environment where there’s no sun or rain—two elements that cause it to break down.

A farmworker picked chiles in Florida during the 2022 season, accompanied by her son (not pictured). She said she brought him with her to prepare him for the grueling nature of work in the fields, in case he decides to follow in her footsteps.

Esther Poveda/Univision

The health impacts of pesticide exposure depend largely on the amount that reaches workers. If instructions are followed correctly, there may be no negative effects. But as exposure increases, farmworkers can experience symptoms from hives or skin rashes, headaches, nausea and vomiting, to loss of consciousness and respiratory failure. In especially high or prolonged doses, the consequences can be even worse.

Quandt points out that in many cases it’s difficult to link symptoms specifically to pesticides, because farmworkers “work hard, have muscle aches … are in the sun, they get headaches. That’s why physicians look for salivation, teary eyes, [frequent] urination, defecation.” But she said that when those symptoms are present along with changes to the pupils: “you can be pretty sure that it’s pesticide poisoning.”

Jeannie Economos said farmworkers often report that doctors in rural areas are not trained to recognize or investigate the origins of a pesticide rash. Instead, they prescribe creams and tell workers they can return to work the next day. That means workers have no record of being exposed to chemicals or enduring a work-related incident. Other activists reported the same.

Of the more than 30 farmworkers we spoke to in Illinois, Florida, North Carolina and Michigan, nearly every one said they’d had at least a skin rash.

To delve into data on agricultural pesticide exposure, we requested figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Occupational Risk Reporting System, known as SENSOR. This office is the EPA's main source of information, but only 13 states in the country are part of the program and they don’t all report incidents on a regular basis. The most recent numbers are from 1998 to 2011.

When broken down by occupation, there were 5,627 immediate pesticide poisonings in those years, with more than 2,800 in agriculture, forestry and fishing, the category that includes farmworkers. California, Texas and Washington had the highest number of reported cases. New data is expected to be released this year.

In response to Univision Noticias, the EPA acknowledged that an “area for improvement” is in the “quantity and quality of data collected on farmworker exposure and incidents related to pesticides.”

We tried for months to obtain recent data from states participating in SENSOR. Only Michigan, where there were some 77,000 farmworkers in 2022, sent detailed information about pesticide exposure incidents in agriculture, including the chemicals involved and, in some cases, the diagnoses. This data is collected through the Michigan State University surveillance program.

Between 2017 and 2022, there were 71 recorded cases of pesticide exposure linked to agricultural work in the state. These are incidents in which those affected suffered from at least two symptoms that are characteristic of exposure to the chemicals. Some of the most common included irritated or swollen eyes, nausea, skin pain or burning, and cough or shortness of breath. In almost 70% of cases it was unclear whether the worker was wearing any personal protective equipment; protective equipment had been used in one of every four incidents.

In Florida, we learned of a very emblematic case related to pesticide exposure in pregnant farmworkers: that of Carlos Candelario.

He was born on December 17, 2004, with a rare syndrome called tetra-Amelia, which is characterized by the absence of all four limbs.

Candelario spent years trying to understand why he was born with the disorder. After learning his own and similar stories, he found the answer: pesticides. His mother, Francisca Herrera, had been exposed to cocktails of chemicals while working in Ag-Mart tomato fields. Unbeknownst to her, she was in the first trimester of her pregnancy, just as Carlos' brain, spinal cord, heart, and limbs were forming.

Andrés Rivera/Univision

The family sued the company over the baby's birth defects. Pediatrician John Reigart was consulted as an expert in the case. “Clearly they were all heavily exposed to pesticides and received no medical care in the field,” he explained to us via Zoom.

Francisca Herrera told Reigart that Ag-Mart workers were sprayed with chemicals nearly everyday, and that those who felt ill weren’t sent to the doctor, but rather were asked to sit for a bit, drink water and return to work.

Images used by Candelario’s legal team to represent conditions in fields. In sworn statements given by different witnesses in the case and reviewed by Univision, the farmworkers agreed that the company did not inform them about the health effects that exposure to the pesticides could cause. They weren’t notified how long they would need to stay off the fields that had been fumigated.

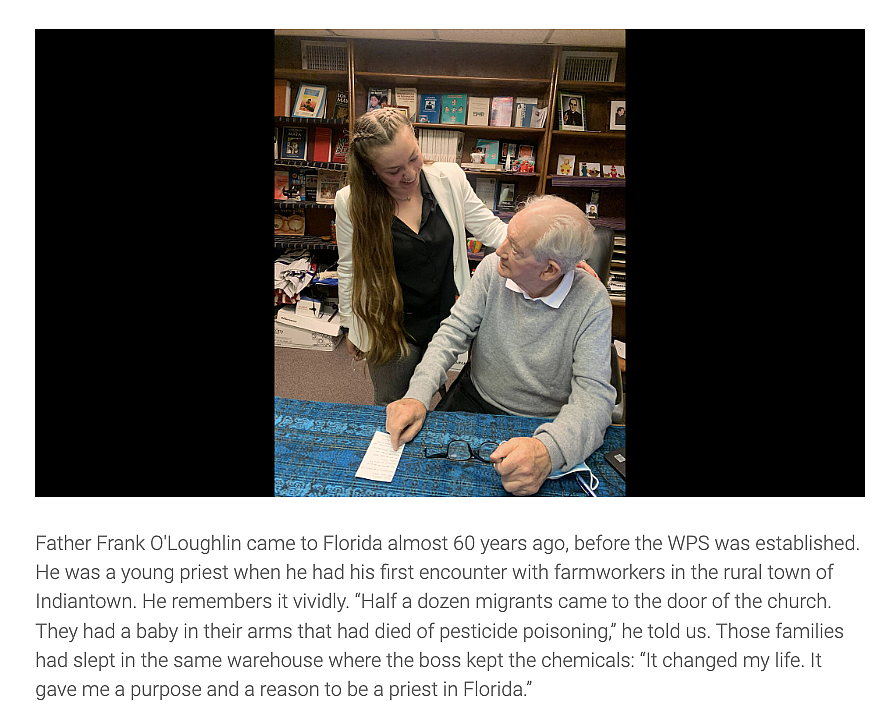

By then, the EPA's Agricultural Worker Protection Standard (WPS) had been implemented to protect farmworkers from exposure to pesticides. But, Jeannie Economos explained, protections at the time were “minimal”: workers were to be trained in pesticide use, but just every five years; employers weren’t required to notify workers if a field had been sprayed, nor did it require them to keep detailed records of the pesticides that were applied.

Esther Poveda/Univision

In addition to Carlos Candelario, two other babies were born with birth defects a few weeks later, according to reports by The Palm Beach Post, which was the first to report on the case. The mothers of the three babies lived just feet away from their workplace, in an area owned by their employer. They had all picked tomatoes from the same Ag-Mart fields in North Carolina and Florida. None of the women had been told that the areas where they were working had been sprayed with pesticides.

The Palm Beach Post opened its March 13, 2005 edition with the story about Francisca Herrera’s exposure to pesticides in fields managed by Ag-Mart. “People have mentioned to me that maybe this has to do with chemicals. But I really don’t know anything about that. I would like to know,” Herrera said at the time.

Andrés Rivera/Univision

The second child, Jesús Navarrete, was born February 4, 2005, with an underdeveloped jaw. Several media outlets reported that he survived. The third child was born February 6, 2005, but died three days later from “massive birth defects,” according to The Palm Beach Post. They included a cleft lip and palate, absence of visible sexual organs, and a single kidney.

“These are fairly rare defects. When you see two that are exactly the same, you have to believe they have the same cause,” Reigart said.

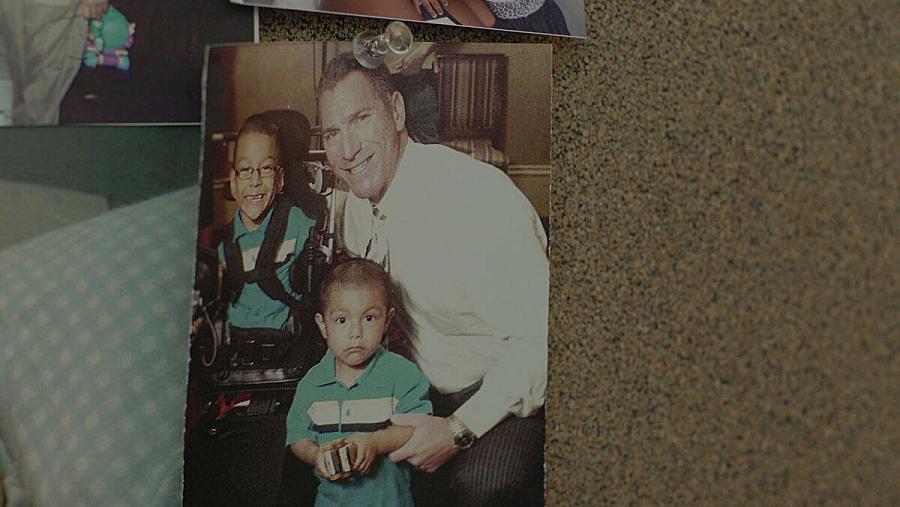

“I want people to understand that pesticides can have disastrous consequences,” Carlos Candelario told Univision Noticias. In the photo, Carlos when he was just a baby.

Federica Narancio/Univision

The pediatrician also told us that the company's lawyers could only provide him with a general list of chemical agents that had been applied to the fields where Francisca worked.

In his analysis Reigart found that some of the pesticides mentioned had been linked to birth defects—similar to those experienced by Carlos and the other children—in studies with animals.

Pediatrician Reigart spoke of his meeting with company lawyers: “They looked at me and said, 'Well, just because it happens in animals doesn't mean it happens in people.' Of course, that's not true because all of the regulation of pesticides for safety is based on using experimental animals. And if the animals have effects, we don't license them for people.”

In 2005, health and agricultural authorities in North Carolina and Florida led an investigation into the mothers’ exposure to pesticides during a critical period for fetal development. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) assisted local agencies in the process.

They used company records that included information on pesticides applied and workers’ locations on certain dates. But the data—provided by Ag-Mart and collected by the authorities—was insufficient to determine a causal link between Francisca’s exposure to pesticides and Carlos’ birth defects. An article about the case published in 2007 in the medical journal Environmental Health Perspectives cited the investigation’s limitations, including potentially inaccurate pesticide exposure records, no known previous studies and the small number of cases.

Nonetheless, authorities determined that the case demonstrated the need to reduce farmworker exposure to pesticides, as well as the importance of following instructions listed on labels.

A 2008 agreement between the family and the tomato producing company Ag-Mart led to a trust that will cover Carlitos’ expenses for life.

The Candelario family lawyer, Andy Yaffa, with Carlos and one of his brothers. The image hangs in his office. Yaffa recalls how brave it was for Candelario's mother to seek help even when she was still living in company housing: “When I met them, it became clear very, very quickly that I had to do something to protect them.”

Federica Narancio/Univision

The case made headlines in the local and national press.

It gave activists evidence to demonstrate the importance of establishing greater protections for farmworkers. In 2015, 11 years after Carlos was born, a new set of regulations made annual training a requirement. Employers were also required to provide notification if a field was sprayed and how long workers should stay away, as well as to keep detailed records of pesticides applied.

In a sworn statement, toxicologist Kenneth Rudo said: “I've been doing this for over 18 years; this is probably the strongest case—from an exposure duration, lack of protection standpoint—that we’ve seen that resulted in an adverse developmental effect to a child whose mother was working in a field.”

Francisca Herrera, Carlos' mother. She has been dedicated to caring for Carlos since he was born. Before the family won the lawsuit, she says they “struggled” to support themselves month after month. They even lived for two months in a homeless shelter because they couldn't pay the rent. She says that no one wanted to hire her husband for fear of a lawsuit.

Federica Narancio/ Univision

The EPA explained in an email that recent changes reflect updates in the risk of certain chemicals seen in Carlitos’ case, such as the fungicide Mancozeb, which has been linked to possible defects in fetal development. Its registration is currently under review; new proposed use instructions will be released this year.

Univision Noticias requested a comment from executives at Procacci Brothers, the parent company of Ag-Mart, but did not receive a response.

In addition to Soria’s case and that of the children born with birth defects, in Michigan we met a woman who survived cancer possibly brought on by prolonged exposure to pesticides.

According to medical anthropologist Sara Quandt, it can be difficult to detect long term impacts among the highly mobile farmworker population.

“There’s no system of tracking their exposures over time,” she said. “So if they develop Parkinson's disease when they're 70 years old or 60 years old, there's no way of attributing that to the pesticide exposure that they received early in their farm working career.”

Over the years, Jeannie Economos has met a number of farmworkers who dedicated their lives to agricultural work only to fall ill with cancer, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis; she’s seen the children of farmworkers face learning problems or autism. All of these conditions have been linked to different pesticides.

“That's a real issue and a real concern for us, because there's no way to track that,” Economos says.

Federica Narancio and Andrés Rivera/Univision

The woman from Michigan who got sick with cancer requested we call her Marta to protect her identity. She was part of a class action lawsuit against Monsanto, the multinational agricultural giant, for failing to specify the potential health effects of its Roundup pesticide. She received financial compensation.

In August 2019, a mammogram showed “something abnormal.” A subsequent biopsy and MRI would explain her permanent state of exhaustion and the strange sweating she was experiencing at night.

“They told me I was full of cancer, that it was stage three (an advanced stage). That moment was very sad because I didn't know what to do,” she told us in an interview in Michigan, where she resides. She wanted doctors to help her understand the origin of the diagnosis.

“When I asked why I got cancer, they asked me where I had worked, if I had contact with chemicals. I told them yes. They said the chemicals could explain it.”

Federica Narancio/Univision

In a sworn statement in December 2021, Marta said her doctor explained that her cancer could be caused by the use of pesticides such as Roundup, whose active ingredient is glyphosate.

Despite its potential health impacts, Roundup is one of the most commonly used herbicides in the United States. There are a range of opinions within the scientific community, including many who allege that exposure to the substance may be associated with a greater risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, the same cancer that Marta had. This type of cancer directly affects the immune system.

However, the company that manufactures the pesticide maintains that the EPA concluded “glyphosate does not cause cancer and approved the Roundup™ label without a warning.”

Marta left Michoacán, Mexico, in 1990. She arrived in Florida when she was just 17 years old and then moved to Michigan: “I came to get ahead, because back home people are very poor, there is very little work and I heard about work in the fields. I decided to come to work and make a better life for my family.”

She spent 26 years picking oranges, grapefruits, tomatoes, apples, blueberries and cucumbers; for about three of those years she was applying pesticides directly to blueberry plants and in nurseries. The last time she remembers spraying pesticides was in 2002.

Federica Narancio/Univision

Marta couldn't read the labels, either.

In 1999, she says she was sprayed by a small plane while picking blueberries: “We never imagined it was dangerous, we weren’t informed. I was exposed to pesticides for many years, a long time.”

She also remembers being in contact with pesticides spread from tractors or by applicators on other farms. And for a few months she lived in a trailer next to her work, where pesticides were also applied, she said in her affidavit.

Marta hadn’t been able to get a mammogram in 2018 because she couldn’t afford it. But in 2019, Teresa Hendricks, director of Migrant Legal Aid in Michigan, obtained funding to bring mobile health units to farmworkers. Marta was able to get the exam for free.

This same organization connected the Mexican woman with the law firm that was pursuing a class action lawsuit against Monsanto.

Marta’s fight against cancer was “very hard.” A foundation helped her pay for her treatment, but not rent, food or support for her three children. So she was forced to continue working, leaving treatments at the hospital to go straight to an onion packing plant. Her nails turned black, her teeth became loose, and she lost her hair.

In February 2020, doctors told her she was cancer-free, but that she should continue to get check ups every three months to make sure the cancer hadn’t returned.

Although Marta was compensated—she can’t reveal the amount due to a confidentiality agreement—she says it wouldn’t have paid for even one cycle of chemotherapy: “With all the money I got, which wasn’t much, I can tell you that nothing can buy life. Money can’t pay for everything one suffers.”

In her sworn statement, Marta said she had also been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis and that there was no history of the disease in her family. Different studies have reported an increased risk of the illness among farmworkers in general and among those exposed to certain pesticides.

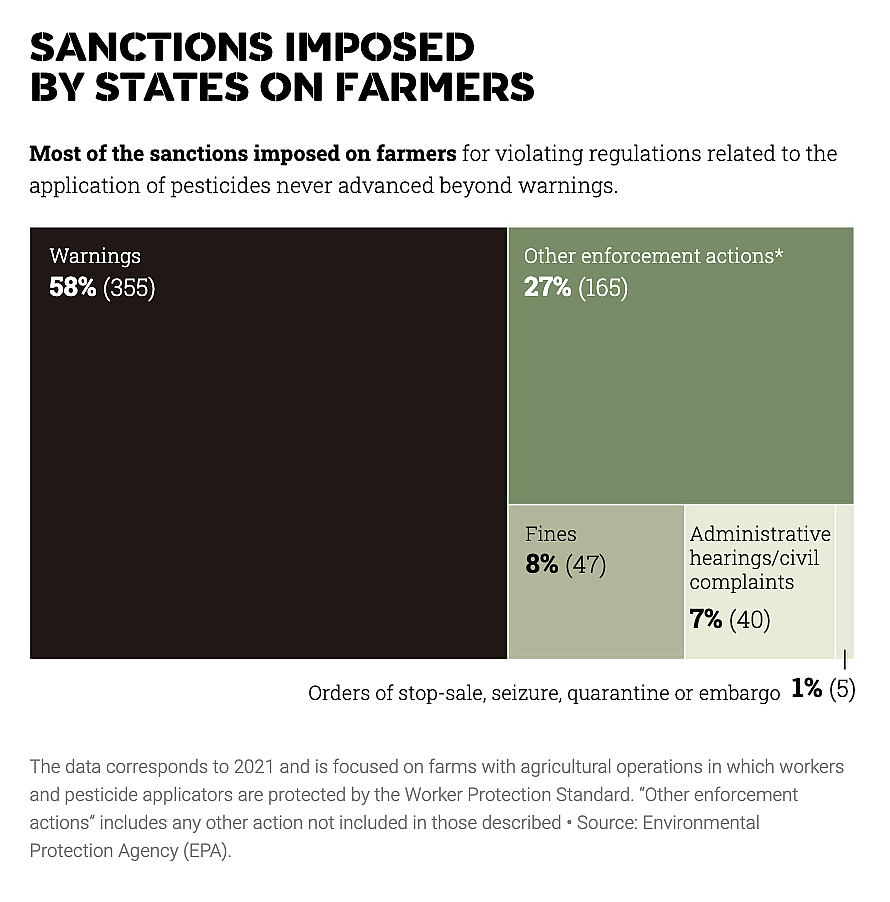

The EPA is responsible for approving pesticides for use and implementing worker protections under the Worker Protection Standard. However, it usually delegates enforcement to state agricultural departments.

Jeannie Economos thinks this transfer of responsibilities is “problematic.” Not all states have adequate resources to inspect agricultural fields, nor the same political will to enforce protections, she explains.

Archival photo from the Library of Congress. The United States began applying pesticides in the 1940s. The photo shows Mexican agricultural workers in California who came through the Bracero program, an agreement in effect between 1942 and 1964 that brought more than 4 million Mexicans to the United States due to a shortage of local agricultural labor during World War II. Migrants who participated in this program were victims of abuse and exposure to pesticides.

Economos and others told us they’d learned of inspectors who regularly call producers to warn them of an upcoming review, which gives them “time to clean up and remove any possible violations.” In addition, authorities rarely fine agricultural companies; they usually only receive a warning. When they do receive financial penalties, the amounts are rarely more than a few hundred dollars, such as in José Soria’s case.

A number of people interviewed told us they’d seen similar systems in other states; even in California, where a Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR), in existence since 1991, oversees commissioners who investigate incidents of chemical exposure.

In an email, the EPA told us that 2015 revisions to the Worker Protection Standard, during the Barack Obama administration, sought to make “great strides in ensuring safe work environments for farmworkers and other pesticide handlers.”

But when Donald Trump took office in 2017, some of the new provisions could not be fully implemented, Martha Guzmán, EPA regional administrator for the nation's Pacific Southwest Region (which includes Arizona, California, Nevada, Hawaii, the Pacific Islands and 148 tribal nations), told us over Zoom.

Guzmán acknowledged that the EPA knows of employers “who are not always concerned about worker health, unfortunately,” and insisted that the agency “needs to do more.”

California—a state Guzmán manages—has been the country’s leader in reducing pesticide exposure in agricultural workers and among rural populations.

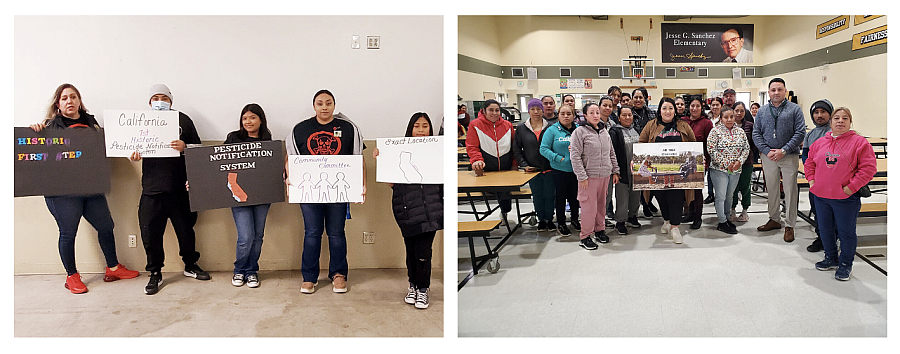

It permanently banned the insecticide chlorpyrifos. This year, the state plans to inaugurate the country's first system for notifying communities of pesticide applications. By January 2026, it will be the first to have an advisory committee to give communities the chance to intervene in state decisions about the use of pesticides.

First: Activists attended a public hearing in Ventura, in December 2023, to discuss the creation of a system—to launch in 2025—to alert the community when pesticides are applied in the area. Second: A Spanish-language workshop was held in Salinas in April 2024 to inform parents about pesticide exposure. Salinas was the site of the country’s largest study to date on children exposed to pesticides, called “CHAMACOS.”

Photos courtesy of Californians for Pesticide Reform

California is also the only state with a Department of Pesticide Regulation (DPR), which is an advantage for farmworkers—but not a perfect solution.

Journalist Claudia Meléndez Salinas, who covers environmental justice for the outlet Voices of Monterey Bay, said the organization imposes limits on the application of pesticides, but often fails to investigate cases of exposure. It’s activists who push for the investigations, she said.

Some experts we spoke with believe that farmworkers will have a voice only when they can unionize. According to Joan Flocks, an emeritus researcher at the University of Florida focused on environmental and social justice issues in the rural population: “It's not easy for them to complain in a certain situation. They're excluded from some protections that other industries get when it comes to worker safety and health.”

María is scared of the harm that pesticides may cause her. Some of her coworkers have gotten sick, she assumes from the chemicals: “The spray affects you,” she says. But she feels she doesn’t have a choice. When they spray you: “you just deal with it.”

She recalls colleagues who were allergic to chemicals and broke out in hives; their bosses gave them ointments and they kept on working. The workers complained, but nothing changed, so they chose to keep quiet and continue in the fields.

Hortencia reported the same. Being sprayed by a plane caused her a trauma that keeps her awake at night, but she continues working in the fields.

Federica Narancio/Univision

Over two years, we spoke with a number of other farmworkers in the same situation as María and Hortencia. They continue to work in the fields because that’s how they support their families.

José Soria still makes his money—much of which he sends to family in Mexico—in the fields. He left the company that ran the fields where he suffered the paraquat burns. He told us that five of his colleagues underwent medical treatment, and two refused healthcare because they feared being fired: “Many of us farmworkers hired in the United States don’t raise our voices, perhaps out of fear of losing a job or opportunity. Even though our lives are at risk, we don’t approach someone to help us.”

Of the workers we interviewed, only José Soria said he was no longer scared to demand his rights.

The only worker we spoke to who chose to leave the fields was Marta. Once her cancer went into remission in 2020, she was too afraid to touch fruits: “I’m not going back to the field. It was honest work, but I’m even afraid of the water that falls from the trees.”

Jeannie Economos took extended leave from her job for about five years. She cried constantly, especially when she couldn’t provide the help that people needed. “Do you know what it's like to have a title that says Pesticide Safety and Environmental Health Project Coordinator and look in the face of a farmworker who's telling me about their pesticide exposure case and say: ‘I can't do anything to help you. Our laws aren’t strong enough to help you’? That is heartbreaking.”