'Failure Factories': In Pinellas County, kids can be suspended for almost anything. And black students are.

Michael LaForgia wrote this story for the Tampa Bay Times as part of a 2015 National Health Journalism Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

How the Pinellas County School Board neglected five schools until they became the worst in Florida

Black leaders say district broke promises made to settle lawsuit

Confederate flag punctuates Pinellas School Board discussion on failing schools

In one Florida county, a skyrocketing failure rate for black children

'Failure Factories': Duncan blasts Pinellas school system for 'education malpractice'

By Lisa Gartner, Michael LaForgia, and Nathaniel Lash

Most large Florida school districts are moving away from suspending children for nonviolent misbehavior — part of a nationwide consensus that harsh discipline falls unfairly on black kids and leaves struggling students too far behind.

The Pinellas County School District is an outlier.

Its leaders say teachers and principals know best, and they should be free to suspend students as they see fit.

The result: Black children in Pinellas are suspended at rates seen in virtually no other large school district in Florida.

They are regularly kicked out of class for vaguely defined infractions like “defiance,” “excessive tardiness” and “electronic device.”

The Tampa Bay Times analyzed a database of more than 600,000 punishments given to children in the district from 2010 to 2015. Then reporters interviewed leaders of the 20 largest school systems in Florida and examined state records to compare them to Pinellas. Among the findings:

- Pinellas County suspends black children at higher rates than the six other large school systems in Florida. Black students in Pinellas were 17 percent more likely to be suspended than blacks in Hillsborough, 41 percent more likely than blacks in Palm Beach and 85 percent more likely than blacks in Miami-Dade. They were six times more likely to be suspended than black children in Broward.

- More than half of the suspensions given to black students are not for the violent offenses detailed by the Times earlier in this series. They’re not even for borderline cases. They’re for hard-to-define infractions such as “not cooperating,” “unauthorized location” and minor “class disruption.”

- In five years, black students lost a combined 45,942 school days to suspensions for these and other minor offenses. White students, who outnumber black students 3 to 1, lost 28,665 days by comparison.

- Pinellas schools give out-of-school suspensions to black children disproportionately. They suspended blacks at four times the rate of other children based on their respective shares of the population. That’s one of the widest disparities in the state. Sixty-three of Florida’s other 66 school districts hand out suspensions more evenly among races.

- The School Board and district leaders have repeatedly rebuffed calls to adopt a discipline matrix, a tool that other districts use to make discipline more colorblind and to keep more kids in the classroom. Just two of the 20 largest school districts in Florida don’t use a discipline matrix. One is Brevard, whose discipline practices are under investigation by the federal government. The other is Pinellas.

- Pinellas leaders have stuck with policies that make it harder for suspended students to catch up. Pinellas doesn’t staff in-school suspension sessions with certified teachers, as other districts do. It cut all funding for suspension centers where kids could do school work rather than stay home while being punished. And it prohibits suspended high school students from earning full credit for make-up work, a practice most other large districts have abandoned because it needlessly sets kids back.

Keeping order in the classroom isn’t easy. The task is made even harder when teachers and administrators are dealing with children who have emotional problems, who are being raised in extreme poverty or who come from broken homes.

“You have to understand that many of these children come in angry,” said Myrna Starling, who retired in 2010 after nearly 30 years teaching at Maximo Elementary. “Some days I would just have to turn the lights off and say, ‘I guess you don’t want to learn.’ Sometimes we would go 10 minutes with the lights off and heads down.”

But there is a growing consensus among national education experts that suspending children for minor offenses is not the answer. Instead, schools should clearly define each infraction and its appropriate punishments. Experts say that leaves less room for teachers and principals to be influenced, even unconsciously, by racial biases.

In an interview with the Times, Pinellas school superintendent Mike Grego acknowledged that unconscious bias plays a role in how often black children are suspended in Pinellas.

But he balked at a one-size-fits-all system, saying teachers and principals must have discretion to do what they think is best. “They know the kid. They know the intent, they know the surrounding issues around that incident,” Grego said. “I believe the way we’re going about it in an intelligent, research-based way is how we’re going to build a different culture. And I see that culture being established school by school.”

Grego noted that, after years of inaction, the district has launched a program to reduce suspensions countywide.

He pointed to a drop in referrals and said suspensions for black children are down 13 percent in the first 60 days of the school year.

He also said that, as of four months ago, the district is compiling the latest research on bias and using it to train principals, so they can avoid bias when punishing children.

But the authors of much of that research told the Times the district should do more to curtail suspensions.

“If they were really serious about addressing this issue, they would follow the examples like L.A., like Oakland, like (Broward), and stop suspending kids for minor offenses,” said Daniel Losen of the Civil Rights Project at UCLA, whose work was cited five times in a recent Pinellas research report. “There’s no justification for doing this. If they were really serious they would change the written policy as well.”

Countering bias

Education experts across the nation agree that the most fair discipline systems are the ones that are most objective.

Research has shown that teachers and administrators, even if unintentionally, tend to punish black children more often and more harshly if the process is left to their discretion.

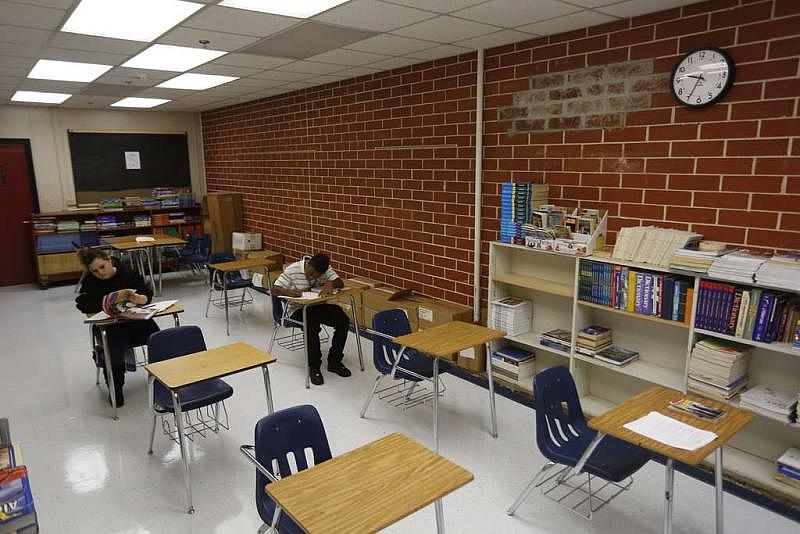

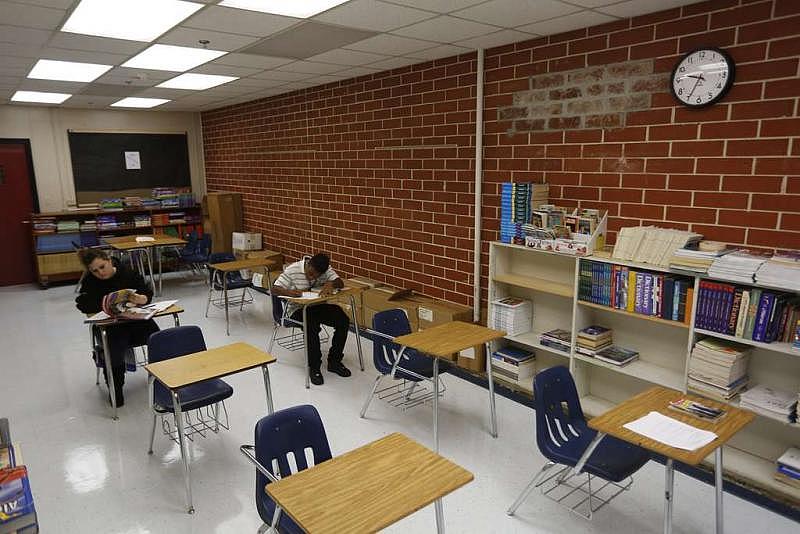

Students serve suspension at West Side High School in Duval County, where school leaders take a different approach to discipline.

The reason is implicit bias — unconscious discrimination against black children by teachers and principals of different cultures, said Russell Skiba, director of the Equity Project at Indiana University and a leading expert in school discipline disparities.

Teachers might interpret a black student’s way of speaking as combative or argumentative, Skiba said. Fear can also play a part, leading teachers who associate black children with danger and threats to overreact to minor misbehavior.

For these reasons, Skiba said, other school districts in Florida and across the nation have adopted discipline systems that put less weight on the judgment of individual teachers and principals and create checks and balances to head off inequitable punishments.

“The less well-defined a discipline system is, the more opportunity there is for differential interpretation and possibly bias to be creeping into that,” Skiba said.

Florida offers several examples of carefully defined discipline plans that calibrate punishments to minor offenses. Some do away with harsh punishments altogether.

“If you just throw them out, we think it sends a message. But it sends a message that you really don’t care,” Duval County school superintendent Nikolai Vitti said. “When students are given out-of-school suspension they start to run with the wrong crowd, become truant, commit crime.”

Students can’t be written up for “defiance” in Duval.

Pinellas punished children more than 100,000 times for that offense in the past five years.

The harshest punishment a student in Palm Beach County can get when they disrupt class for the first time is Saturday school.

Pinellas has pulled kids out of regular classes and given them in-school suspensions for that infraction more than 35,000 times since 2010.

Hillsborough County students are not disciplined simply for being in an “unauthorized location.” Pinellas suspended children more than 1,700 times for that offense.

Broward County teachers and principals use a computer system that won’t let them select a punishment that is too harsh for certain minor infractions.

Miami-Dade no longer gives children out-of-school suspensions, opting instead to send students to “Success Centers” staffed by teachers and counselors.

The latitude Pinellas teachers and principals get is supposed to empower them to do what’s best for children. But in a school system where eight in 10 teachers are white, black kids are punished far more often than other children.

There were 19,300 black students in the district last year, but blacks were disciplined more than 52,000 times.

White students, who outnumber blacks 3 to 1, were punished 42,000 times by comparison.

The Times’ analysis of district data found that the disparities go further than how often black students get sent to the office compared to whites. When children of various races are written up for the same offense, black children are more likely to get harsher punishments, the Times found.

Take students who got in trouble for “excessive tardies,” which the district defines as “the act of arriving late to class or to school on a repeated basis.”

White students were punished for that offense about 5,800 more times than blacks in the past five years. Yet blacks got 79 more out-of-school suspensions for tardiness than whites.

They were three times as likely as whites to be assigned to a work detail — a punishment that requires students to pick up trash or do other odd jobs that might otherwise fall to janitors.

Extreme case

Gibbs High School is ground zero for the disparity in punishments of blacks and whites.

The district opened Gibbs as an all-black junior and senior high during the segregated 1920s. Today, nearly two-thirds of the school’s 1,300 students are black. The majority are enrolled in traditional classes, while most of the school’s white and Asian students attend a separate arts magnet housed on campus.

The school has struggled with student behavior, including some high-profile episodes of violence. Last year, a video recording of a vicious classroom fight between two girls at the school went viral on the Internet. A year before that, a teen was arrested at the school for allegedly carrying a loaded gun. Those types of incidents have led parents and district leaders to call for a harder line on discipline at Gibbs.

Black students at Gibbs High School are far more likely to be suspended than other students.

But the vast majority of discipline referrals go to students who commit minor offenses. And measured by how often black students are suspended compared to other children, Gibbs is the most unfair school in Pinellas County.

Black students at Gibbs are more than seven times as likely as other students to be suspended out of school.

For common, minor infractions, black students often faced harsher punishment than white students written up for the same thing. ATimes analysis of discipline records showed they were twice as likely as whites to be suspended last year for causing a minor class disruption — an infraction that is not defined or described in the school’s discipline guidelines.

Every school in Pinellas writes its own discipline plan. The one created by Gibbs allows students to be removed from the classroom for 32 of 34 listed misbehaviors.

Under the Gibbs guidelines, a student who talks back to a teacher can get the same punishment as a student who injures a classmate in a violent fight.

Naomi Gaines was struggling to make up lost time at Gibbs after transferring in midway through high school in 2013. She said she quickly came to know the school as a place where black students could land in serious trouble for the smallest things.

Gaines said she saw students written up for laughing too loudly, for wearing tights and for being seen in the hallway holding a cellphone.

She recalled getting a referral last year for having a pair of headphones — not plugged into anything — on her desk

The offense listed on her discipline slip was possession of an electronic device, she said, and the punishment was three days on an “alternate bell schedule” — a form of suspension that requires students to miss their normal classes and instead come to school at 2:30 p.m. and spend five hours sitting in a classroom.

The altered schedule posed problems for Gaines. She didn’t have access to a car. She lived nearly an hour’s walk from Gibbs. Her parents, who both work, couldn’t leave their jobs at 2 p.m. to drive her to the school.

Unable to report for the punishment, Gaines said she pleaded with administrators to work out some other arrangement. She said they told her she couldn’t return to regular class until she served all of her suspension days in full.

Gibbs principal Reuben Hepburn told the Times that the school typically works with students who have transportation issues and can arrange for bus passes. But Gaines said she asked for one and was refused.

Two weeks passed before she could arrange to be at school and serve her punishment. She wasn’t allowed to go to class the entire time.

During the alternate bell schedule hours, she said, the teacher who ran the suspension didn’t teach the students or require them to keep up with class work. Instead, Gaines said, the teacher told them “to find something to do.”

By the time she was finished, Gaines said, she was frantic at the thought of not graduating because of so much missed class.

In the end, she managed to graduate in June. She now plans to study nursing at St. Petersburg College.

But she knows it could have gone the other way if she hadn’t stayed up night after night to make up the missed assignments.

“I was crying all the time. I broke down. I did not know what to do,” she said. “I was failing, and I was failing so bad to the point where I was really about to give up.”

No secret

It was obvious even to white students at Gibbs that blacks were punished more often and more harshly, said Claire Ison, who is white and who graduated from the school in June 2015.

Ison said she often walked past administrators while cutting out of classes early her senior year, and they never said a word to her. Black students were routinely stopped, Ison said.

“As a white student I honestly did feel like I got away with more than a black student would,” she said.

Teachers, too, were aware of the disparities.

Polled by the district in 2014, a third of the staff at the school said students of different ethnic backgrounds were not treated equally.

Gibbs High Principal Reuben Hepburn takes a tough approach to discipline.

District leaders told the Times they are making progress in reducing suspensions thanks to the new training program. At Gibbs, there were 41 percent fewer suspensions for black students in the first two months of this school year compared to last year, they said.

Interviewed separately, the principal at Gibbs, Hepburn, acknowledged that black students at his school are punished disproportionately. Hepburn, who is black, said it’s because black students break the rules more. He said he believes in a tough approach to bringing students in line.

“My philosophy — and I know it’s not always a favorable philosophy — is we’re going to hit you hard on the front end, and then coach you on what the right thing is,” he said. “We believe in a hands-on approach, and I mean by that, we’ll go upside your head. But we’re the first to high-five you when you’re doing right.”

During the interview, Hepburn played a Fox News clip that he described as “powerful.”

It lambasted the idea that students who commit violent acts should get counseling rather than face immediate expulsion.

“If you have bullies and thugs allowed to remain in the classroom,” the commentator said, “the good teachers, they’re not going to put up with it.”

Resisting change

Across Florida, other school districts are using a tool to make punishments more fair.

Known as a discipline matrix, the system defines punishable behavior and calibrates punishments to fit the crimes. It explicitly spells out which behaviors merit which consequences rather than leave the decision up to teachers.

A matrix takes the guesswork out of student discipline and helps ensure all students are treated equitably, experts say. It also bars suspensions and other harsh punishments for minor infractions.

Eighteen of the 20 largest school districts in Florida use some form of discipline matrix.

Miami-Dade’s system prevents principals from giving students more than in-school suspension for minor class disruptions. Pinellas suspended students out of school more than 12,000 times for that offense in the past five years.

Orange County’s matrix blocks suspensions for profanity. Pinellas has suspended children more than 9,500 times for swearing since 2010.

Hillsborough’s matrix prohibits administrators from suspending children the first three times they’re caught with a cellphone or other electronic device. Pinellas suspended children more than 1,000 times for that offense.

Black parents and community leaders in Pinellas have pressured the school district for years to adopt a discipline matrix. But the School Board has so far refused.

Board members haven’t been convinced by success stories in other school districts, including Broward County. Leaders there revamped a matrix in 2013 and saw out-of-school suspensions given to black children fall by more than half.

“Broward is a different makeup than we are. They are a different culture than us,” said Rene Flowers, the board’s sole black member, while rebuffing the NAACP’s calls for the program in fall 2014. “When you try to fit what someone else is doing, it doesn’t work because it’s not your community.”

In May, Grego told School Board members that it’s important for schools to be “the final decision maker” in discipline cases. “That’s where I think some of the weaknesses are with these so-called matrices because it ties the hands of the administrators,” he said.

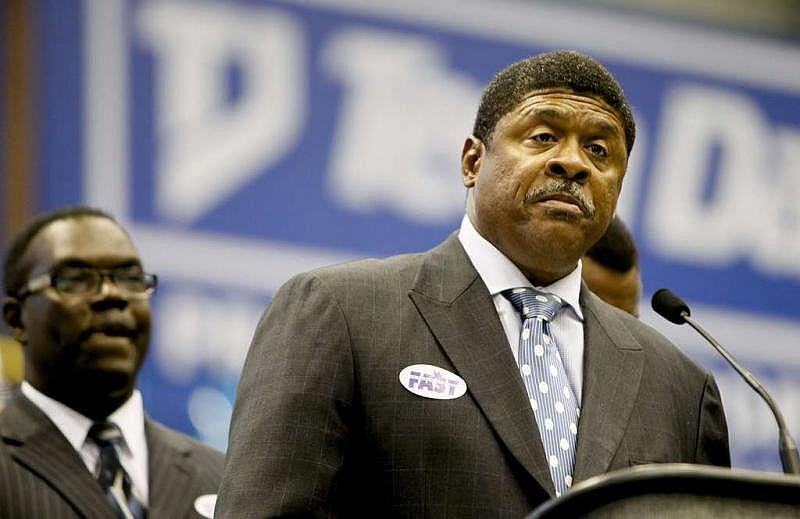

The Rev. Manuel Sykes of Bethel Community Baptist Church calls on the School Board to make discipline more fair.

At a community gathering weeks earlier, a multifaith religious group invited all seven School Board members to address calls for a discipline matrix. Only one — then-chairwoman Linda Lerner — showed up.

Standing near the empty seats of her colleagues, Lerner told the crowd the district didn’t need the discipline tool.

“I do not support that if it’s a particular offense it has to be a particular intervention,” she said. “I certainly will have an open mind in the future.”

Black leaders responded with frustration, but not surprise. They said they’ve been calling on the board for years to take basic steps to make discipline more fair.

“More stonewalling. More arrogance,” said the Rev. Manuel Sykes, pastor of Bethel Community Baptist Church in St. Petersburg, after the meeting. “It’s pretty clear that they’re not going to listen to the concerns of parents and other community people when it comes to what’s best for our children.”

Constantly on edge

When children are suspended in Pinellas, they have fewer chances to make up the work they miss than they would in other Florida districts.

Eight of the state’s 20 largest school districts require in-school suspension sessions be led by a certified teacher to help kids complete schoolwork while suspended.

Six districts, including Hillsborough, have centers where suspended students make up work with teachers and counselors instead of sitting at home.

Thirteen always give students full credit for work done on suspension.

In Pinellas — where black children are failing at some of the highest rates in Florida — district leaders have cut funding for programs designed to keep students from missing lessons.

They opened alternative behavior centers that drastically cut down on the number of black children suspended from middle schools in the mid 1980s, only to discontinue them within a few years.

They created on-campus suspension centers in the late 1990s that were praised by Harvard researchers as “a program with clear benefits” and a national model for keeping order in schools while ensuring black children still got a good education. But the School Board would not fund even one of them in full — they cost about $100,000 apiece — and discontinued the program when outside money ran out in 2008.

Board members and district leaders pledged in 2010 to train teachers how to use “positive behavior supports,” a classroom management system that puts a premium on getting troubled kids help for their problems while keeping them in school. But the board allowed five years to pass before ensuring that teachers were trained. The training only began again in earnest in the past two years.

Superintendent Grego told the Times that the district could do more to ensure students don’t fall behind during punishments. “We need to continue to look and stretch ourselves on that. Alternatives to out-of-school suspension are important. They’re expensive,” he said. “But I’m looking and we as a staff are looking at ways we can mitigate that cost and still have that instructional time.”

In a district where even minor misbehavior can lead to harsh punishments and lost class time, many black children are constantly on edge.

Avontrell Hazzard said he had to think twice before laughing after what happened at Mount Vernon Elementary.

The 13-year-old said he was eating lunch with his friends in spring 2014 when a teacher singled him out for being too loud. He spent the rest of the day in the office, filling out worksheets he had already completed in class.

Fifteen-year-old Jaquan Henderson, who has asthma, recalls not being able to catch his breath after his first-grade teachers at Lakewood Elementary pinned him to the floor over a temper tantrum. He was 7.

Jaden Lee said he paid a high price for a simple misunderstanding.

One day in October, the seventh-grader chose a brownie from the lunch counter at Joseph L. Carwise Middle School and asked the lunch lady to charge it to his school account. He thought he had the money to cover it. He said the lunch lady told him he did.

Two hours later, Jaden — one of about 70 black kids at the 1,100-student school — was called to the front office. There was no money in his account after all, an assistant principal told him. She accused him of stealing the 50-cent baked good and gave him an in-school suspension, a punishment that took him out of class for a full day.

The 12-year-old reported for the punishment the next day, spending the 6 1/2-hour suspension in a spare room with another student.

After settling in, he pulled out a worksheet from his civics class but discovered he couldn’t complete it. His teacher hadn’t given him the book he needed for the assignment, his mother told the Times.

As his school day ticked away, he stared down blankly at the worksheet, not knowing what it covered.

It was a review of the 14th Amendment. The part of the Constitution used to strike a blow for black children in Brown vs. Board of Education.

[This story was originally published by the Tampa Bay Times.]

Photographs by Dirk Shadd/Tampa Bay Times.