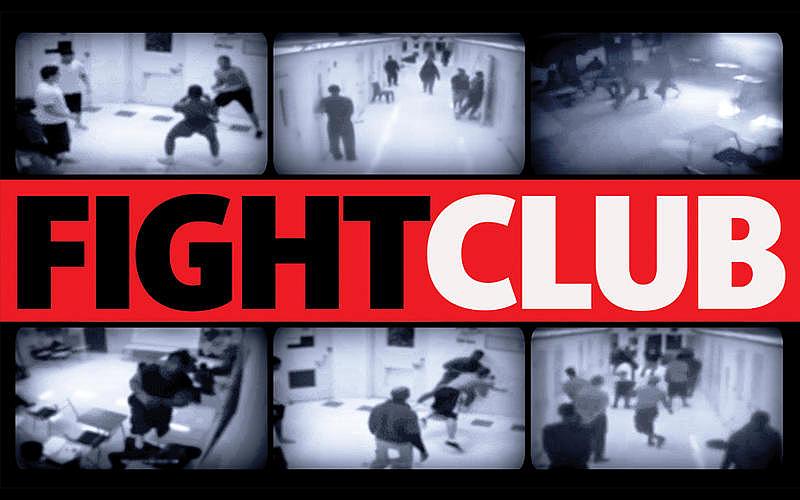

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

MIAMI HERALD

By Wilson Sayre and Carol Marbin Miller

Emory Jones just needs to look at his left arm for a reminder of what happened at Avon Park Youth Academy. There is a faint scar in the shape of a snake above his elbow from when an officer beat him.

When Emory was 14, he started burglarizing homes. He said he wanted nicer things than what his family could afford and was first busted by police in 2011. A Broward County judge sent him to a Department of Juvenile Justice program on the grounds of an Air Force bombing range in rural Polk County.

Emory Jones looks at scars left by beatings from a DJJ officer.

One night in the summer of 2013, Emory and a group of teenagers were playing video games, cursing and talking trash.

Uriah Harris, one of the officers at the program, heard them using profane language and he offered them a choice: whacks from a broom or demerits — that could add time to their sentence.

“He called it broomie, ‘Go get broomie,’ ” recalled Emory of one of the numerous times he was beaten.

The math was simple: Two hits with a broom versus extra time.

Harris had been hired to work with kids despite a rap sheet that included resisting arrest, domestic violence, aggravated battery and child neglect.

The inspector general for the Department of Juvenile Justice substantiated three different claims that Harris was beating kids as a form of discipline. It amounted to excessive force.

Harris denied the allegations, calling the kids he supervised “master manipulators,” but he was fired.

Cases like that of Emory Jones are not unusual in Florida’s Department of Juvenile Justice (DJJ).

Palm Beach Youth Academy, one of the facilities in the DJJ system.

Spurred by the death of 17-year-old Elord Revolte after a fight in a Miami-Dade County juvenile lockup, the Miami Herald undertook an exhaustive investigation into the state’s juvenile justice system. Over the course of two-years, journalists found a troubled system beset by lax hiring standards, low pay, sexual misconduct and beatings bought for the price of a pastry.

Staffers sometimes employ harsh takedowns, ignore abuse and offer snacks as bribes for beatdowns—known as “honey-bunning.” One youth called his compound a “fight club,” where youth officers arranged bouts.

Listen to the audio version of the investigation in three parts (audio below).

The Department of Juvenile Justice is tasked with rehabilitating young Floridians who get in trouble with the law, sometimes for serious crimes. To that end, the department runs detention centers and oversees so-called "commitment facilities.” Every one of these facilities in the state operated by a private provider and overseen by the state.

“Unfortunately it seems to be a few bad apples in almost every single program that we've had contact with,” said Gordon Weeks, who is in charge of the juvenile division of the Broward County Public Defender's Office.

“It is not appropriate for a child to be told by the court that the court is going to send them to a program with the intent of rehabilitating them ... but, when they arrive at the program, they realize that all those promises fall short, that the program is just a prison,” Weeks continued.

The starting salary for a Department of Juvenile Justice employee is $25,000 a year. Florida’s largest private operator starts new workers out at less than $20,000. Recently, Gov. Rick Scott proposed a 10 percent increase for DJJ workers, though that will still have to go through the legislative budget process.

“Extremely concerned. That's my first initial recollection of having interaction with some of the staff,” said Josie Ashton, who worked in DJJ facilities for more than three years. She was brought in to train incoming employees on how to interact with children.

“I laugh because it was really disturbing at times, their hiring practices. Basically if you can breathe and talk and walk, ‘Yeah, we want you here.' If you’re willing to take $8.50, $9 an hour, 'Sure you can work with us,” said Ashton of the DJJ, describing contractors’ attitudes towards hiring.

'Close To Home' is the program used by the juvenile justice program in New York. Here is one of the group homes in that system. The idea is to reduce the number of kids in a program and relocate the program from rural New York state back to the neighborhoods these kids come from. They also employ a therapeutic approach to rehabilitation as opposed to a punitive approach, which Florida employs.

Many employees Ashton worked with were former prison guards, about 350 of whom state-wide were hired to work in the DJJ system after being fired or allowed to resign while under investigation for wrongdoing by the Department of Corrections.

And when workers do something wrong — like punch a kid in the face — it's rare that they face consequences.

A lot of times their bad behavior is covered up by fellow officers and supervisors.

Over the past 10 years, the DJJ has investigated more than 1,400 cases of allegedly failing to report wrongdoing — or lying about what happened. That’s an average of about three a week.

Things like aging and faulty surveillance cameras make it much harder to prosecute wrongdoing. The department has known about this problem for 15 years, according to findings by the Miami Herald.

“We have got thousands of dedicated people in this agency. I would put our staff up against a lot of other agencies,” responded Christina Daly, secretary of the Department of Juvenile Justice, to questions about the uncovered abuses.

“This happening to one child is too often, in my mind. We have policies in place of what your relationship should be like with these children. Not everyone follows these policies and procedures. But the best we can do is have them in place," said Daly.

In others states, juvenile justice programs have paired policy changes with a totally different kind of environments.

And that has proved to be far more effective than the Florida system.

[This story was originally published by WLRN.]

[Photos by Emily Michot/Miami Herald.]

Listen to the audio version of the investigation in three parts.