Going granular: Why deep dives into health data can help kids in poor zip codes like 32304

This story was produced as a project for the 2019 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

13 million missed meals in Leon: 'Meal Deficit Metric' aims to track hunger across Florida

Coronavirus: Lack of access to tests hampers care in Tallahassee's poorer neighborhoods

At 32304's Riley Elementary, staff 'serve a greater need than just educating the mind'

'No access': Poor, isolated and forgotten, kids of 32304 see their health care compromised

Distanced from assistance: Rampant health problems in Gadsden mirror coronavirus risk factors

‘Our kids aren’t growing up’: Epidemic of gun violence scars, kills Tallahassee’s Black children

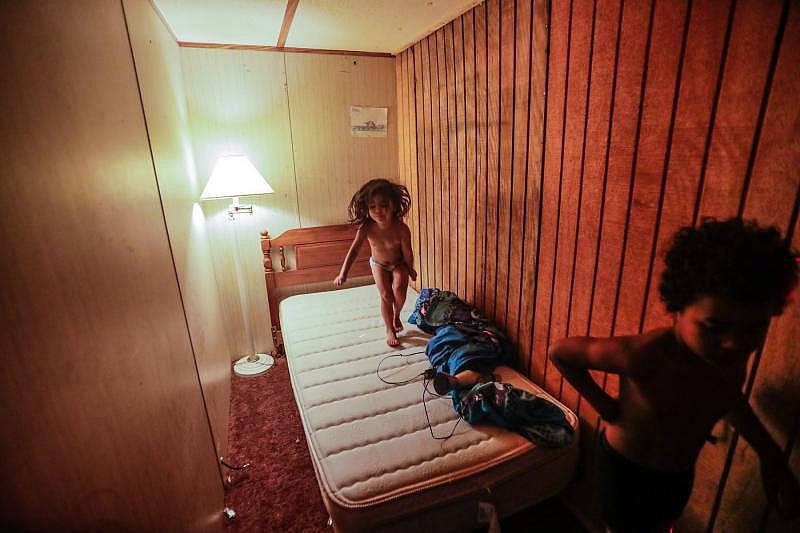

When the Florida Chamber of Commerce released its zip code calculations, the news of 32304's poverty astonished leaders throughout the capital city.

It prompted county commissioners to create a multi-part summit throughout 2019, gathering local health, school and law enforcement officials to brainstorm ways to improve quality of life throughout the community.

It also drew skepticism. Many questioned whether the Census numbers were “skewed” by college students since Florida State University is in 32304.

But a U.S. Census spokesman said student dormitories and other housing aimed at students aren’t counted among households. Instead, they’re tallied under a Census-designated group quarters category, along with prisons and nursing homes.

According to a Center for Health Equity community needs survey, stakeholders said zip code 32304 was most affected when it came to lack of access to preventative health services and health insurance.

But underlying data is far from precise or transparent, obscuring the scope of health issues kids face in specific neighborhoods.

Children’s health issues can be analyzed by county using the state health department’s Health Charts website, yet there’s almost no data available about children’s health by zip code. A state health department spokesman replied to a public records request pointing to county-wide data as “the most specific available.”

And even for the little zip-code data that is available, such as infant deaths, the state cites federal privacy laws and redacts any numbers less than five per zip code.

The state does, however, provide data on maternal health by zip code. Between 2014 and 2018, the latest available, 32304 had the highest reported number of babies born to moms without a high school education in Leon County: 268 births out of 1,756, or 15%.

Data from local hospitals obtained by the Democrat shows hundreds of children from high-poverty zip codes such as 32304 and the south side’s 32305 go to the emergency room for asthma and oral health-related issues, like toothaches. Experts know both types of ER visits are a key indicator of disparities in health-care access.

Within just the last two years, about three times as many children in 32304, 32301, 32305 and 32310 went to the emergency room for asthmatic symptoms when compared to kids from affluent 32312.

About 140 from zip codes 32304 and 32305 went to the ER for toothaches and other oral health problems. Only 13 children went from 32312.

Service workers and health-care professionals on the ground know where the problems are — and what they are. But they lack the resources to increase awareness and implement solutions. A proposed taxpayer-funded children's services council aims to support and improve existing resources for children's health. Voters will decide the fate of the initiative in a referendum on the November ballot.

One of those resources is the Molar Express, a low-income dental clinic run by the county health department, is nestled near Florida A&M, in Railroad Square.

Dr. John Bidwell, the office’s senior dentist, used to run a private practice in affluent Killearn in northeast Tallahassee before transferring to the clinic to treat children under Medicaid. The differences between the two areas is huge.

“The parents are used to having their kids going to the dentist twice a year,” Bidwell said. “They have a sense of value of teeth. (Here) the parents are not aware … they just, for lack of a better term, plain don’t know.”

Parents are unwitting and tend to think if there’s no pain, there’s no problem, he explained. As a result, many of the children he sees have far-gone dental problems.

“When they start having toothaches, usually the problem is a fairly significant problem. Some teeth are beyond hope. We can’t fix them even if we wanted to do,” he said.

A few miles away from the Molar Express, Mabry Street Head Start case manager Melody Henderson tries to increase dental health awareness by helping parents find a dentist and scheduling appointments for their 3- and 4-year-olds.

She remembers a pair of siblings from 32304 with rows of rotted teeth who were later placed in foster care.

The American Dental Hygienists’ Association has been advocating for dental therapy programs to expand access to dental care inside at-risk communities.

Last year, Connecticut joined a growing number of states to implement dental therapy programs when its legislature passed a bill authorizing them.

Alaskan dental therapists paved the way for the program almost two decades ago. There, experts report improved dental health of indigenous children, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts.

During this past Florida legislative session, a proposed dental therapy bill failed to pass.

'You can't turn back the clock'

With zip code data from the state failing to produce hard numbers on children’s health, advocating for resources to correct inequities like poor dental health in a specific part of town is tricky.

Other communities, however, have found ways to dig deeper and mine data to better target resources to solve health inequities.

In California’s Alameda County, health department officials began analyzing life expectancy by zip code. After the team found people in poorer zip codes died earlier, they formed a task force and plan to address health disparities within the affected geographic lines.

In Leon County, adults in poorer zip codes also die earlier than those in more affluent zip codes, state health data shows. In one Census tract on the city’s south side, off South Adams Street where the average per capita income is $15,500, the average life expectancy is just 65 years old — the lowest in the city.

Just 10 miles away, those adults die two decades earlier than those in a section of affluent Killearn, where the $138,000 median income is the city’s highest and the life expectancy of 88 is the longest.

In one Census tract in 32304, adults on average die at 73.

Some statisticians argue that getting granular with data using zip codes and other even smaller units like Census tracts and block groups can help communities identify and target specific issues, like food insecurity.

A Census snapshot of your community: Compare population, education, household income, poverty levels, real estate info and more

Mari Gallagher, a Chicago-based researcher, developed a “Meal Deficit Metric” for the nonprofit Feeding Florida that calculates missed meals at the block-group level.

“Granularity is important for allocating resources because there is a lot of variation across counties,” Gallagher said. “We need to know exactly where the meals are missed – and these pinpointed units of measurement direct anti-hunger leaders to those families in need. And this takes the guesswork and the stereotypes out of the war against hunger.”

Back story: 13 million missed meals in Leon: 'Meal Deficit Metric' aims to track hunger across Florida

Most Census tracts in zip codes 32304 and 32310 are part of the Promise Zone — city-designated areas that suffer from high poverty and crime rates. The town’s low-income health clinics, such as Bond and Neighborhood, are trying to take health services into those communities to eliminate access barriers.

But more mobile health units are needed.

Because families move so often trying to find cheaper rent or move in with relatives, follow-up appointments are elusive with old addresses on file. The outcome is clinics like Bond see high no-show rates among children living in poverty.

“A child can only do so much. They’re at the mercy of their parent or their guardian,” said Bond's Dr. Temple Robinson. “If you have high no-show rates, then you have missed opportunities for well-child visits, immunizations — and you can’t turn back the clock.”

This story was supported by the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2019 National Fellowship and the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Reach Nada Hassanein at nhassanein@tallahassee.com or on Twitter @nhassanein_.

[This article was originally published by The Tallahassee Democrat.]