Healing Through Ethnic Studies: Empowering Asian and Pacific Islander Incarcerated Communities

The story was co-published with AsAmNews as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

A symposium of the Restoring Our Original True Selves (ROOTS) symposium in 2015 at San Quentin state prison (renamed San Quentin Rehabilitation Center in March 2023) in California.

Photo courtesy of APSC

The Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC) based in Oakland, California, has been providing in-prison Asia-Pacific-focused ethnic studies and community-based social services to a growing population of incarcerated Asians and Pacific Islanders and their families.

Eddy Zheng, a formerly incarcerated Chinese American around whom the APSC formed as a movement 22 years ago, has consistently told the press that education and, specifically, ethnic studies, saved his life during and after imprisonment.

He believes that learning gave him the empowerment, self-esteem, confidence, and purpose to heal from trauma, account for the individual choices that led to his incarceration and cope with the experience of being incarcerated itself.

Research has repeatedly revealed that education overall, while not a replacement for the mental health care and educational opportunities lacking in prisons, leads to better health outcomes, lower rates of recidivism, and economic savings and gains for society.

A 2009 study by the Urban Institute Justice Policy Center revealed that students had heightened feelings of intelligence, pride, confidence in their ability to do something worthwhile, desire to be a good example in their communities, and the ability to form future goals and plans.

Ethnic studies provide a culturally competent version of these benefit, countering the dehumanization and violence of prison environments and helping incarcerated people understand and heal from the historical, systemic, and personal traumas surrounding their incarceration.

In many cases, these positive effects create agents of change and leaders with the lived experience and motivation to break the chains of mass-incarceration disproportionately affecting their communities.

Support for incarcerated Asian people in America

The APSC was formed in 2002 by UC Berkeley undergraduate Anmol Chadda, civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama, student and community activists at UC Davis and others to free “The San Quentin 3” — Eddy Zheng, Viet Mike Ngo, and Rico Remedio.

Zheng, Ngo, and Remedio, all incarcerated at San Quentin state prison, ended up in solitary confinement after circulating a petition to bring Asian and Asian American studies into the institution. They had been inspired by volunteer in-prison educators from the University of California, Berkeley protesting proposed cuts to ethnic studies on their own campus.

At the time, Zheng, incarcerated as a minor and serving a life sentence with the possibility of parole, had already been behind bars for 16 years — half his life.

The fight for ethnic studies took place during a downturn in federal support for educational programs in prisons.

In the early nineties, nearly 14% of people in state prisons across the U.S. had been enrolled in college courses while incarcerated. In 1992, an amendment to the Higher Education Act rendered people serving life sentences without parole and those sentenced to death ineligible to receive Pell Grants, a federal student aid program.

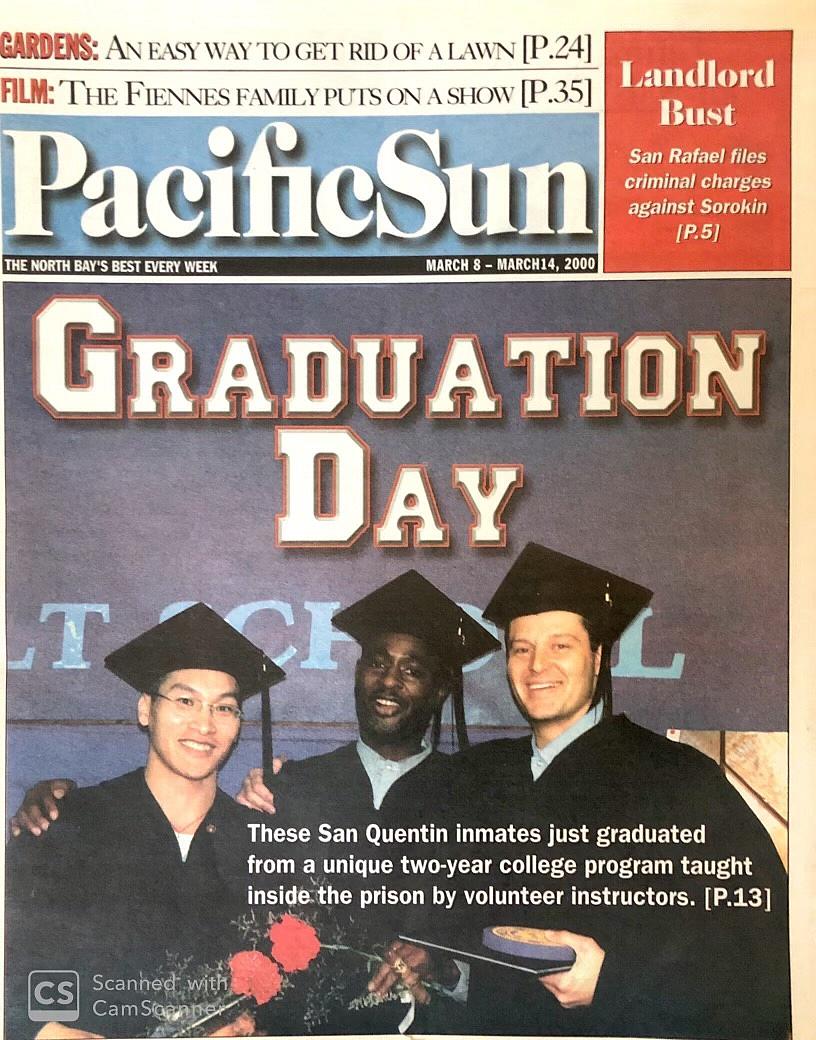

A newspaper commemorating when Eddy Zheng, left, received his associate’s degree inside San Quentin state prison in the year 2000 at age 30, after 14 years of incarceration.

Photo courtesy of Eddy Zheng

Then, a provision of the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, the largest crime bill in the history of the U.S. to date, expanded the ban to all incarcerated people. By 2004, the cuts had halved participation in in-prison college courses.

With the help of APSC’s campaigns, Zheng was released from isolation after 11 months. APSC lived on as a volunteer-run advocacy organization serving incarcerated and formerly incarcerated Asians and Pacific Islanders.

Zheng was granted parole under Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger (R) and handed from prison custody directly to the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in March 2005.

An immigrant, Zheng had lost lawful permanent residency when convicted of his crimes. After detaining him for two years ICE released Zheng in February 2007 after 21 years of incarceration. He was 37, lacked citizenship status, and still faced the possibility of deportation at any time.

Breaking the prison to deportation pipeline

Zheng came to Oakland from Guangzhou, China with his family in 1982 when he was 12. His life changed drastically. When he could not comprehend English in high school, he skipped classes and played kickball with other Chinese immigrant kids in the park as American teens jeered, “Vietcong” and “Ching-Chong Chinaman.”

Zheng started doing small errands for gangsters offering pocket money. The tasks escalated into thefts and robberies, and a job working the night shift at a brothel in San Francisco with a shotgun in his hands.

On January 6, 1986, Eddy, then 16, and two other teenagers invaded the home of a business-owning family in San Francisco’s Chinatown, terrorizing the parents and children. After ransacking the house, the teens drove the mother to her shop and stole the money from the establishment. Police pulled Zheng over on the return trip for having his headlights off.

Zheng was tried as an adult and convicted of 16 counts plus kidnapping. His family could not afford legal representation. Zheng pleaded guilty to his wrongdoings on his parents' advise.

Upon receiving a sentence of seven years to life in prison, Zheng was held in juvenile detention centers until he turned 18 in 1987 and entered San Quentin State Prison as the youngest person there.

He said that education can disrupt trajectories like his.

“You have to address the mental health aspect. And then you have to provide them with the education that they didn’t receive when they were supposed to receive in their formative years.”

The late civil rights activist Yuri Kochiyama (left) and formerly incarcerated Eddy Zheng

Photo courtesy of APSC

He added that now, only specific prisons have rehabilitative services such as self-help programs, peer-facilitated groups, workforce skills development, and other means of engagement.

Zheng said, “You have to create wraparound services – support the people and not continue to punish and dehumanize harmful people. If they’ve already caused harm, they’re traumatized people, they’re hurt people. You continue to dehumanize them and add on more layers of trauma to them? That’s not going to work.”

Healing inside of prison

Nghiep Lam, who goes by Ke (“key”), overlapped for a couple of years with Zheng in San Quentin but didn’t meet him until 2010.

Lam made a beeline toward Zheng and his APSC colleagues when they came to the prison as part of an annual health fair. At the event, Eddy discussed developing an ethnic study program focused on Asian American and Pacific Islander culture, history, and healing.

Ethnically Chinese, Lam was born in 1976 in Hai Phong, Vietnam a year after the fall of Saigon and the withdrawal of U.S. armed forces from Southeast Asia.

Fearing the ruling Viet Cong, the family fled in 1977 as one of many “boat people,” stranded for weeks in the South Sea before being rescued by fishermen in exchange for all their valuables. They were towed to Hong Kong and placed in a detention facility for two years before being granted visas to come to the US in 1980.

When he was 7, Lam and his family finally settled in San Francisco in 1983. His parents separated shortly after moving into the Tenderloin district. When Lam and his mother moved to housing projects on Potrero Hill, he encountered daily bullying. Some of the kids threw rotten eggs at him, chased him with dogs, and physically assaulted him.

Lam had no memories of his family’s journey to America. He always figured he had been born in the U.S. even if he did not understand the language being spoken at school.

Early on in his education, a teacher labeled him a disruption for not understanding English and banished him to the hallway until the ESL instructor arrived. Lam could not find much guidance at home – his single mother was working two jobs to feed her two sons.

In 1991, his mother moved him and his siblings across the Bay Bridge to Richmond. It was Lam’s first time associating with other Asian people, and gangs – he turned to one for protection and belonging.

In 1993, when he was 17, he and his friends approached some rivals. Lam stabbed one of them in the back before running off. He turned himself in the next day and learned that the person he stabbed – another teenager – had died.

Lam was tried as an adult and convicted of aggravated felony, and then cycled through juvenile institutions before arriving at the DeWitt Nelson Youth Correctional Facility (shut down on Jul. 31, 2008). Within hours, he got into a race riot between Asians and Mexicans.

“I just heard a commotion. I ran over there to check it out. And so one of the guys I knew, one of the Vietnamese guys, was fighting. So I just ran and jumped in,” he said.

Guards stripped Lam down to his underwear and threw him into a harshly lit isolation cell, turning the air conditioner up on high until Lam felt like he was in an icebox. He attempted to wrap a skinny, uncovered mattress around himself to survive.

“There weren’t too many programs, you know, to help somebody change their life, or given the opportunity to do that introspection work,” he said, of the maximum security institutions where he went next.

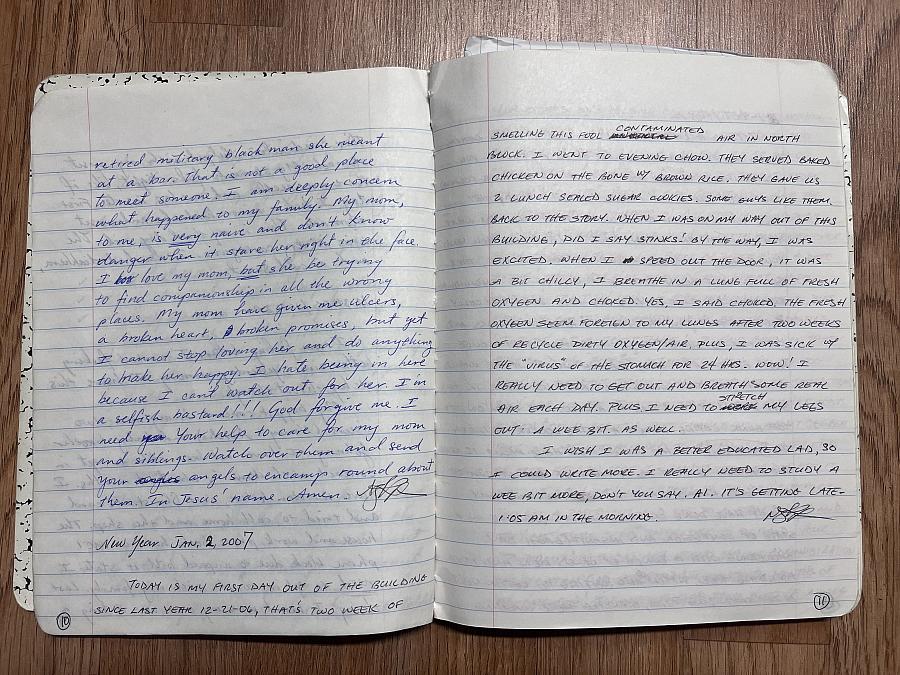

Pages from Nghiep “Ke” Lam’s journal from when he was incarcerated.

Photo Courtesy of Nghiep “Ke” Lam

Around 1995, he started journaling about what he could not discuss with anyone else. He self-censored to some extent so that no one who found his diaries could use his thoughts or feelings against him.

In higher security prisons, Lam took the advice of older “lifer” Filipinos, who suggested that he take advantage of any self-help or education programs available. These were usually ministry-led workshops and Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. He quit smoking and drinking and earned his G.E.D.

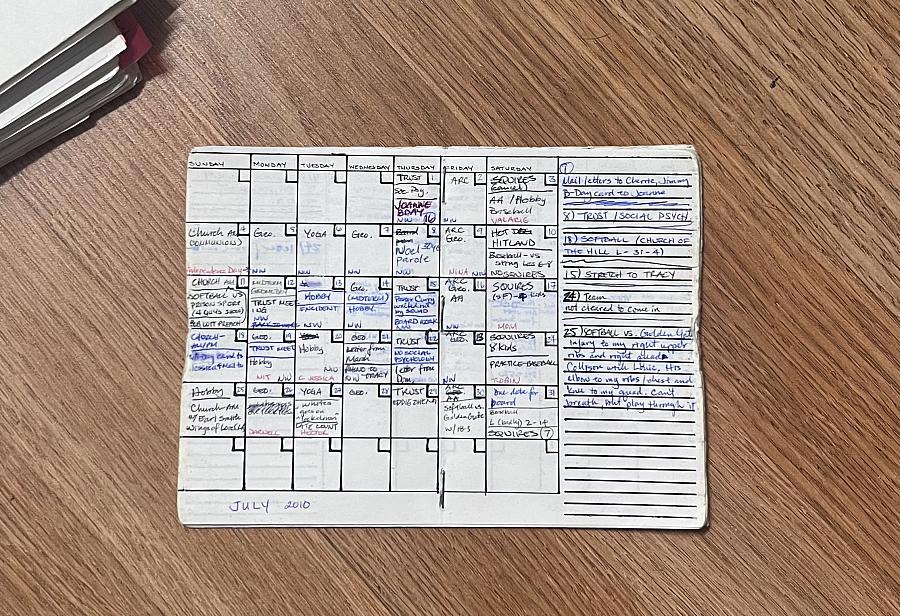

A snapshot of Nghiep “Ke” Lam’s activities when he was in San Quentin State Prison.

Photo Courtesy of Nghiep “Ke” Lam

“It was ridiculous,” Lam said, describing the change once he moved in 2003 to San Quentin State Prison, which had a wealth of rehabilitation opportunities, educational programs, and recreational activities. His calendar was full from five-thirty in the morning until lights out at nine o’clock at night with sports and lectures.

Around 2005, he was passing by the holding area of the prison when someone called him by name. It was his cousin, who informed Lam that his younger brother had died in a car crash in 1999.

When Lam’s brother had visited the prison a few years before his death, Lam had ended up pushing him and telling him to step up as the man of the house.

That was the last time they saw one another.

After losing someone so close to him, Lam realized the impact he had left on the family of the boy he had harmed years ago. He redoubled his attempts to atone for the life he had taken and the brother he had lost.

By the time his path crossed with Zheng’s, Lam said, “It was a no-brainer – like, let’s do this. Yeah, I’d be down to know more about my culture and history, as well as the other folks, other APIs.”

Everyone in prison grouped themselves by race, and Lam estimated that there were 85 people of Asian or Pacific Islander background at San Quentin in his time.

Planting ROOTS

What became the Restoring Our Original True Selves (ROOTS) in-prison ethnic studies program began as a proposal for a “multicultural group” sponsored by the predominantly Black organization San Quentin T.R.U.S.T.

The acronym ROOTS was coined by Stephen Yair Liebb, who left prison after serving for 19 years and now works at the Integrity Unit of the San Francisco Public Defender’s Office for the release of reformed people from incarceration.

Zheng and Ben Wang, then the co-directors of APSC, established the curriculum along with co-facilitator Kasi Chakravartula (still an APSC council member), and vital sources on the inside, like Lam.

ROOTS began with the specific intention of healing trauma and strengthening the mental and emotional well-being of incarcerated Asians and Pacific Islander people.

A 2022 press release of the Prison Policy Initiative (PPI) announced that 48% of all incarcerated people have been diagnosed at least once with a mental health condition but that 3 out of 4 people in prison who require mental health care do not get it.

Mental health services in overpopulated, understaffed prisons consist of medicating and pacifying the incarcerated, or performing psychiatric evaluations for their trials or release.

Zheng said that ROOTS worked by breaking down historical events so that people can connect the dots to the origins of their trauma and the harm they have committed.

The course also created a space to discuss feelings about life before and during imprisonment. Zheng said that this was critical for those in the community who had learned to power past their feelings without talking about them.

“If you look at the historical repression of not expressing your feelings in our cultures, that in itself is a mental illness,” he said.

In 2014, ROOTS started piloting classes in San Quentin, which Lam attended. Experts from all fields and perspectives visited with insights on the culture and history of the Chinese, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Hmong, Lao, Filipino, Korean Japanese, Fijian, Polynesian (Hawaiian, Samoan, Tongan), and more subgroups that had been lumped together “Other” on prison intake forms.

Cultural performers such as Japanese taiko drummers, dancers of Māori haka, and Asian and Pacific Islander B-boy breakdancers and poets performed and conversed with the audience afterward.

One day, a husband and wife duo introduced the concept of intergenerational trauma. Lam was floored. Not in all the U.S. history and Asian history courses had anyone ever mentioned the mental health and emotional ramifications of events like the war that drove his family to America.

He flashed back to childhood memories of his parents yelling, slamming doors, and laying on high expectations. He remembered his grandparents, who screamed and cussed at one another every night for 60 years of marriage.

“And the next day, they was cool!” Lam exclaimed. “I realized, no, that’s not effective communication or healthy communication. So the ROOTS program actually broke down not only that, but our connection to imperialism, Communism and the loss of our culture. And loss of our culture is when we forget to speak our language, and we adopt other people’s cultures in place of our own.”

In December 2015, Lam was paroled, and, like Zheng, turned directly over to ICE for having lost his lawful permanent residency status upon conviction. U.S.-Vietnam repatriation laws blocking the removal of immigrants who arrived in the U.S. from Vietnam before 1995 led to his release.

Nghiep “Ke” Lam, reentry navigator of the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC), outside his office in Oakland, Calif. In his spare time, Lam fixes bicycles to give to people impacted by incarceration. He is one of the APSC4 “stranded deportees.”

Photo by Jia H. Jung

But unlike Zheng, who ultimately received a pardon in 2015 from Governor Jerry Brown (D) for his past convictions and obtained U.S. citizenship in 2017, Lam remains one of “The APSC 4” – core staff members who are “stranded deportees.” Deportable by the U.S. and rejected from their origin countries, they lack status in any country and must apply for work permits every year to stay in the States with their families.

Having lost his permanent resident status because of his crimes, Lam cannot apply for asylum or citizenship unless the governor pardons his past convictions, even though he has done his time and is a working, taxpaying member of American society.

Nevertheless, once Zheng and Lam were both out in the world, they kept strengthening “inside-outside” networks to sustain and grow APSC’s programs.

Healing outside of prison

Nate Tan, an ethnic studies instructor and the current co-director of the APSC, also first met Zheng in 2010 when Zheng spoke at one of his ethnic studies classes.

Tan, who had grown up knowing family members who had been in and out of prison and deported, said, “It was the first time that I experienced an organization that worked with a population of people that was reflective of my experience in the United States.” He jumped to volunteer.

Tan was born and raised in Alameda County to a Cambodian mother and father who fled the Khmer Rouge genocide and came to the U.S. in 1981 and 1984, respectively.

“I didn’t have a model on how to get to college, you know, refugee parents are like, figure it out, we got here, it’s up to you, now. And I didn’t figure it out until I met this girl,” Tan explained.

She told Tan that she didn’t date anyone who didn’t go to college, eventually prompting him to enter a program intercepting students statistically destined not to attain higher education. An ethnic studies course was on the menu.

The class was Tan’s first exposure to themes of inequality, injustice, and systemic violence in the form of racism, patriarchy, and economic exploitation.

“It really moved me, like really transformed how I saw my place in this world, my family’s positioning in this world, what odds were stacked against me and my community,” Tan recalled.

He went on to become the first in his family to attend and graduate from college. He earned a Master’s degree in ethnic studies from San Francisco State University, where the field was pioneered in 1969.

“I was like, if I was moved enough to change the trajectory of my life, maybe I can be that instructor for other students,” he said.

The first time that he ever set foot in a prison was as a volunteer ROOTS instructor at San Quentin. He had never seen so many Cambodian people in one place except during Cambodian New Year.

Tan began “sharing the light” that, while responsible for the harm of past choices, people could also begin holding accountable the systems that had defined their communities’ living environments.

Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC) co-director Nate Tan, left, and reentry coordinator Chanthon “Bun” Bun, second from left, at the 2022 VISION Act Rally in Sacramento. The law, which would have prevented prison-to-ICE transfers, failed by three votes in the Senate.

Photo by Joyce Xi Photography, courtesy of APSC

Ethnic studies create better mental health pathways

Decades after becoming the first Asia-Pacific-focused ethnic studies course in any prison, ROOTS is still the only sustained program of its kind in the nation, administered by APSC workers and volunteers, ROOTS graduates, college and university faculty, and other guests.

ROOTS takes place in San Quentin every second and fourth Monday of each month if there isn’t a lockdown due to riots, sickness, or fog that obscures visibility from the watchtowers.

This year is the seventh cycle of the approximately year-long course that many have taken for healing, self-development, and community. APSC is now also piloting Lit Club, an ethnic studies-based correspondence course for people at Solano state prison, Santa Rita county jail, ICE detention centers, and women’s facilities.

The course, open to people of all backgrounds, starts with the sharing of personal stories. Participants reflect together about the role trauma played in their circumstances and choices, and talk about what they need to address that trauma.

Themes of discussion include Asian and Pacific Islander history and culture, war, genocide, refugee experiences, migration, displacement, poverty, intergenerational trauma, race, gender identity, and the penal system.

ROOTS and the ROOTS 2 Reentry (R2R) program for formerly incarcerated people have healed and transformed hundreds of people. An educational video on PBS gives a glimpse into the continuing impact of ethnic studies in prison.

“Proving” these effects is the quest ahead.

APSC’s latest statistics reported a 5% recidivism rate of R2R participants, compared to the state rate of 41% and a national rate of 48%, according to the latest recidivism report by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR).

Tan said that APSC refers re-entry program participants to mental health resources and practitioners at multilingual partner organizations such as Center for Empowering Refugees and Immigrants and Asian Health Services, which has a Community Healing Unit. Referral and diagnosis data from these cases remain confidential.

McArthur “Mac” Hoang, APSC’s re-entry manager, said, “To the majority that says we have to prove that ethnic studies creates better mental health pathways – prove that it doesn’t. That’s an easy rebuttal for the question of how ethnic studies helps mental health. What would majority America feel if they lost their history? If they lost their Washington?”

Hoang said being “othered” by both Americans and by Asians around the world presents fundamental mental health challenges while in a state of invisibility. The antidote to this, he said, is the restoration of cultural identity, belonging, and hope that ethnic studies provides.

“‘Know thyself’ – it’s been written for years, for centuries,” he said. “But many of us, because we’re a small population, don’t learn about ourselves or our people through traditional educational systems,” he said.

Hoang and Zheng began working together after crossing paths at a conference. Hoang remembered seeing Zheng floating around San Quentin in the late 1990s, looking like a ghost.

He said, “In my scholarly athletics on how much harm being an “other” causes, I have discourses with other American scholars. And the discourse usually ends when I say, ‘I can pontificate about your culture: how much do you know about mine?’”

He warned that ignoring the need for ethnic studies over dehumanizing punishment is dangerous.

“More harm creates more harm,” he said. “America is just a fleeting moment in time and space, and all societies, including the Romans, are judged by how well they treat the most vulnerable.”

“It’s like, yes, to be able to ‘prove it,’ we need to have the data, and the resources to get that data,” Zheng added. As president and founder of New Breath Foundation (NBF), he has been building these resources on a larger scale.

Since incorporation in 2017, NBF has distributed $6.1 million in resources to 57 grassroots organizations focused on NBF’s core values, the first of which is hope and healing.

Hoang is a member of the board.

“You don’t recover from mental health disparities; you find a way to exist. It’s not a binary. We’re not just fixed,” Hoang said. “People need support; a lifetime of support.”

Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC) reentry manager McArthur “Mac” Hoang on graduation day at the University of California, Berkeley.

Photo courtesy of McArthur “Mac” Hoang

Not just about educating

Tan said that APSC receives many letters from educators, community organizers, and incarcerated people asking about getting ROOTS in their institutions. The office has received inquiries from incarcerated Cambodians in Massachusetts, whose city of Lowell is home to the second largest population of Cambodians in America after Long Beach, California.

ROOTS is not easy to duplicate. First, its host institution is uniquely disposed toward rehabilitative and restorative programs. San Quentin might have the highest death row population in the nation but has counterintuitively become known as one of the most progressive prisons in the country. It is also the only prison in California with an onsite degree-granting higher education program that has been around since 1996.

Last May, Governor Gavin Newsom announced that San Quentin will thenceforth be converted into a rehabilitation facility as part of a new “California Model” of providing education, job skills training, and therapy, using Norway’s systems as the leading example.

Ethnic studies programs attempting to penetrate other institutions may contend with environments that lack basic mental health care and educational programming, let alone resources for culturally competent services.

Federal legislation passed in 2020 restored Pell grant funding to all incarcerated individuals by the fall of 2023. The policy change is still grinding into implementation and the first degree program to offer Pell Grants to incarcerated students will launch in California this fall. If or how these changes impact Asians and Pacific Islanders depends on who continues watching and counting the benefits.

Meanwhile, APSC continues to be powered by formerly incarcerated people who were in ROOTS while in prison or started off as volunteers for the organization.

“One of the things I love about the ROOTS program is that it’s not just about educating the folks inside, but it’s a pipeline to leadership,” Lam said.

A founding member of ROOTS, he is now an APSC reentry navigator with approximately 20 reentry clients. He helps them with the paperwork and logistical tasks necessary to function in life after prison. He checks in on everyone individually.

“We talk about self-care a lot – what are they doing to take care of themselves? Because I know a lot of guys, when they come home, and women, when they come home, they want to take care of everyone else,” he said.

Tan said that ethnic studies is also the cure for self-blinding model minority myths and the good/bad binary when regarding the incarcerated.

“I think when we understand the root causes of violence and injustice, we also understand compassion. We understand what it means to be compassionate towards ourselves, and compassionate towards other people in similar circumstances,” he said.

Zheng calls connecting to one’s identity, learning about and humanizing others, and finding solidarity in the struggle toward collective liberation from systems of dehumanization and mass-incarceration the reclamation of CHI: Culture, History, and Identity.

The acronym has the double meaning of chi, the Chinese word and concept for breath and energy – something Zheng says he had to recover to get to where he is today.

Lam’s personal project as soon as he got out of prison was to start showing affection to his family, starting with his father. This lunar new year, he collaborated with 18 Million Rising’s Brenda Chi to issue a graphic art presentation of his journey in breaking the chain of intergenerational trauma between him and his father, one hug at a time.

“Me working with APSC is my way of making amends for the harm that I caused the community might be doing. Me living right, not drinking, smoking, doing all that, is me honoring my victim’s family and my brother and my family,” he said.

He is taking care of himself, too. He invests in therapy sessions every two weeks, even if the co-pays are high.

Much of the healing catalyzed by ethnic studies is incalculable and lifelong.

Reentry navigator Nghiep “Ke” Lam, left, and reentry manager McArthur “Mac” Hoang, right , the Oakland offices of the Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC).

Photo by Jia H. Jung

This AsAmNews project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong Ethnic Media Collaborative reporting venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.