The health care system is leaving the Southern Black Belt behind

Reporting for this story was supported by the Center for Health Journalism’s Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism and the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-being.

Other stories in the series include:

Patterns of death in the South still show the outlines of slavery

Sitting outside of a Starbucks on the corner of a strip mall in Tuscaloosa late last year, Dr. Remona Peterson described her hometown of Thomaston, Alabama, population 400. “Everybody loves our grocery store. That’s, like, our pride,” she said with a laugh. She was in Tuscaloosa, Alabama’s fifth-largest city, finishing her medical residency when Dave’s Market opened in an old Thomaston high school gym last year. Peterson said it became the only place to buy groceries for miles in any direction, and it was one of the few changes to the town she can remember from the last three decades.

Peterson wants to be a part of positive change in the region, which is why she’s back after a circuitous journey through medical school. She was valedictorian of her 29-person high school class and graduated summa cum laude from Tuskegee University, where she earned a full scholarship and the university’s distinguished scholars award. She went on to medical school and got the residency in Tuscaloosa. It was her first choice; she felt that the University of Alabama would best prepare her for her long-term goal: to add her name to the short list of African-American doctors working in the Alabama Black Belt who were also born and raised there.

The Black Belt refers to a stretch of land in the U.S. South whose fertile soil drew white colonists and plantation owners centuries ago. After hundreds of thousands of people were forced there as slaves, the region became the center of rural, black America. Today, the name describes predominantly rural counties where a large share of the population is African-American. The area is one of the most persistently poor in the country, and residents have some of the most limited economic prospects. Life expectancies are among the shortest in the U.S., and poor health outcomes are common. This article is part of a series examining these disparities.

The disparities partly stem from a lack of access to care — but access is a complicated notion. Early in the Republican efforts to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act, the GOP homed in on the idea, saying the party wanted to guarantee “access to health care” for everyone. But the ongoing national policy conversation has hinged on insurance coverage, the main issue tackled by both the Affordable Care Act and the current GOP efforts. Yes, measuring who’s insured illuminates one way by which people have access to the health care system, but it’s only part of the picture. The term “access to health care” has a standardized federal definition that’s much broader: “the timely use of personal health services to achieve the best health outcomes.” And there’s a list of metrics to measure it. Researchers consider structural barriers, such as distance to a hospital or how many health professionals work in an area, to be important. As are metrics that gauge whether a patient can find a health care provider that she trusts and can communicate with well enough to get the services she needs.

Southern states have health outcomes that are among the worst in the U.S. overall, and they have some of the largest in-state health disparities, according to County Health Rankings, an annual report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin. Transportation options are limited, and health care worker shortages are routine. In Alabama, Black Belt counties have fewer primary care physicians, dentists and mental health providers per resident than other counties. They also tend to have the highest rates of uninsured people. Poverty rates, which are associated with limited access to care, are also high.

Becoming a doctor in the Black Belt

John Zippert and his wife, Carol. John works with the farmers cooperative that connected Peterson with Greene County Hospital.

Peterson knows these challenges well, but she objects to people viewing the region as hopeless. “The Black Belt is just so much in need. I don’t want to be looked at … as though people are dumb. And people do look at us like that,” Peterson told me. “Some people just need opportunity. Like me, I needed that opportunity. Someone just gotta give us a chance.”

Peterson likes to acknowledge the help she got during her quest to become a doctor. Her impressive résumé masks the deeply rooted challenges she encountered growing up. Her parents were teachers, which gave her family financial stability, but the largely segregated public schools she attended had little in the way of supplies or technology. She had some great teachers, including a chemistry teacher who Peterson credits with her love of science, but she was shocked by what her classmates already knew when she reached college. “I’m looking around the room like, ‘how do people know this?’ I was lost,” she said. She went on to win an award from the university in her freshman year, for best chemistry and math student. Though she was always a straight-A student, testing wasn’t her forte, and she had trouble with the MCAT, the exam required for entry to most medical schools.

She enrolled in a master’s program in rural and community health, trying to buy time to lift her test scores. She finished the master’s, but didn’t raise her test scores, so she ended up at medical school on a Caribbean island, working simultaneously on an MBA that allowed her to receive some U.S. student loans to pay tuition. After two years she was back in the U.S., her family tapped out of money, trying to figure out how to pay for the rest of her degree.

Then, Peterson was connected to a hospital near her hometown via a farming cooperative she’d worked with while getting her master’s. She explained her situation to the hospital administrator, and, thrilled by the idea of a doctor from the area coming back to work in the community, he struck an unusual deal: Greene County Health System, about midway between her hometown and Tuscaloosa, would pay for the rest of Peterson’s education if she agreed to work there after she graduated. She readily accepted. She found a program she could finish from within the U.S., and in 2014, she graduated from medical school.

Insurance and access

Greene County Hospital is in a low-slung brick building a couple of blocks from the center of Eutaw, Alabama. The town has hollowed out over the years, though its past riches are still on display in the Kirkwood plantation house, and empty stores line the main square. The hospital was hit hard by the county’s shrinking population, which is about 8,400 — less than a third of what it was in 1860, when more than three-quarters of the population were slaves. Jobs and potential patients have evaporated. But the dwindling population isn’t all that makes it hard for the hospital to stay afloat, CEO Elmore Patterson III said.

Greene County is high on poverty and low on resources; centuries’ worth of inequalities have led to major health disparities. And the hospital suffers from problems plaguing rural health systems across the country — too many uninsured people, patients who are sick and have few resources, and aging infrastructure.

The mix of people who use the hospital’s services also poses a financial challenge. People with money and private insurance mostly travel to larger cities to seek care, which means most people using Greene County Health System are uninsured or on public insurance like Medicaid or Medicare. About 7 percent of patients have commercial insurance, Patterson said, and about 8 percent have no insurance at all. This affects the hospital’s bottom line.

Doctors, policy experts and even some state officials say an important but controversial first step would improve access to health care: expanding Medicaid.

Nearly half of the people who use the Greene County Health System now are on Medicaid, the public health insurance program for low-income people. Having so many patients on Medicaid is a stress on the system because the program offers lower reimbursement rates for care than other health insurance providers, Patterson said. But from the hospital’s perspective, it’s far better than a patient having no insurance at all.

Alabama allows broad access to Medicaid for children; anyone under age 18 in a family earning below 312 percent of the federal poverty level, or about $76,000 for a family of four, qualifies.1 But Alabama is one of the most conservative states when it comes to access for adults. Healthy, childless adults aren’t eligible for Medicaid, no matter their income, and parents must make below 13 percent of the federal poverty line to qualify. “You don’t have any healthy people on Medicaid in the state of Alabama,” Patterson said. That means a lot of care and little money to pay for it, he said.

Even though Medicaid doesn’t pay a lot, the uninsured patients are even more of a strain on the system. Adult men working for low hourly wages without benefits have no realistic way to buy health insurance, and they often end up in the emergency department when something goes wrong, Patterson said. That was meant to change with the Affordable Care Act. The law was written to expand Medicaid in every state, in theory reducing the number of uninsured people using hospital services, and so it cut some of the federal government’s reimbursements for care provided to the uninsured. But after the Supreme Court ruled that states could choose whether to expand Medicaid, Alabama, like most of the Black Belt states,2said no thanks. The result has been less support from the federal government for uninsured patients, many of whom would qualify for Medicaid under the expansion.

“The Black Belt is a road map,” said Patrick Sullivan, a professor at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University who previously worked on HIV surveillance at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “That’s what’s so tragic and so compelling. It’s an endgame depiction of what happens when you have social and structural inequalities. It’s the vestiges of slavery and inequality, and in the long run those things do play out as health inequalities.” Sullivan and colleagues have studied why HIV rates are so much higher among African-Americans and Latinos than other racial groups3 and found that health insurance is the most important mediating factor. People in both racial/ethnic groups are more likely to be poor and have less education, which are related barriers, but insurance coverage is where the local and federal government could improve access to treatment, Sullivan said.

Since most Southern states chose not to expand Medicaid, there’s no clear way to dismantle that barrier. And a GOP push not only to roll back the expansion but also to shift costs onto states for the longstanding parts of the program could leave even more people uninsured or with access to fewer services.

Structural barriers and access

Greene County Hospital has been struggling for years. Its operating profit margin is -19.5 percent, according to an evaluation by the Chartis Center for Rural Health, making it one of the worst-performing rural hospitals,4 financially speaking, in Alabama. Care is often more expensive to provide in rural settings, where hospitals are too small to negotiate the best prices for supplies and equipment. The bills the GOP has proposed to replace the ACA would make the problem worse: Cuts to Medicaid would disproportionately hit rural hospitals, which largely depend on funding from the program.

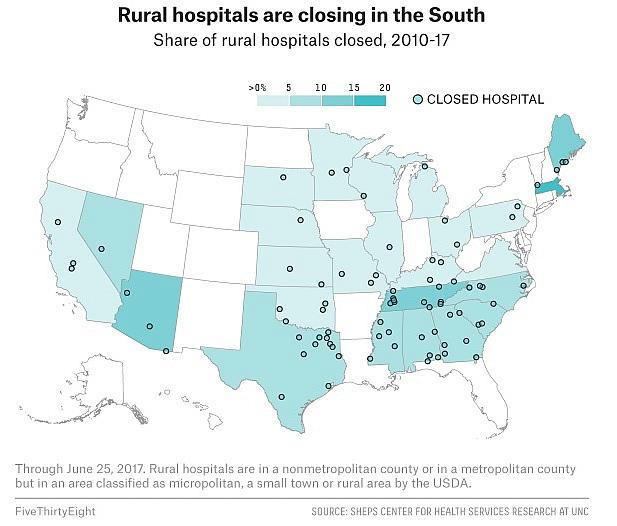

Other rural hospitals are collapsing under the weight of these problems, too. Nearly 80 have permanently closed in the U.S. since 2010, according to data compiled by the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina. Alabama alone has lost five of 54 rural hospitals since 2010; several more, like Greene County’s, operate in the red.

Having to travel long distances for essential care can be a barrier to access. People who live far from emergency rooms are more likely to die from emergencies such as heart disease or accidents. People in rural areas also frequently live farther from pharmacies and are less likely to receive preventive services. For example, there is no prenatal care available in Greene County, Patterson said, which is a problem in much of the Black Belt and in other rural counties across the U.S. The Greene County Health System can provide a few basics, such as prenatal vitamins, but pregnant women must travel for an ultrasound. That’s also the case when it’s time for women to have their babies. It’s nearly an hour-and-a-half drive to Tuscaloosa from Peterson’s hometown, Thomaston, but the nearby labor and delivery unit in Demopolis closed in 2014. During Peterson’s residency, she met women who had given birth in the car while making the drive to a hospital.

States are looking for solutions, alternatives to full-service rural hospitals, to create new kinds of geographical access to care. Some places are considering the use of freestanding emergency departments. There’s also a movement toward allowing nurse practitioners to take charge of more services than they are currently allowed to provide. But these ideas require additional research and regulatory changes. In the meantime, rural hospital systems are often the only option for communities when an emergency strikes. Patients need facilities, and those facilities need to be reimbursed for care if they are going to survive.

Dr. John Waits in the clinic he started with his partners.

Some places have found creative ways to buck the closure trend. In Centreville, just north of the state-defined Black Belt, the Cahaba Medical Care facility serves a largely low-income population, and a quarter of patients are black. It’s attached to a county hospital, and together they opened a labor and delivery unit in 2015. It was the rebirth of a facility that had closed about 15 years before. The man who led that effort, Dr. John Waits, also runs the only rural family medicine residency in Alabama and is part of a small but tenacious group of Alabamians trying to expand training options for doctors who want to work in rural communities.

Waits, who is white, grew up in a conservative, Christian Alabama family with a father who was a surgeon. His conservative beliefs extended to the health care system, and he spent a summer as an intern at the Family Research Council, fighting Hillary Clinton’s 1993 effort to overhaul health insurance. He then studied medicine, assuming he’d work as a missionary abroad. But after his residency, he found himself at a hospital in Centreville, a rural town southeast of Tuscaloosa. He remembers being blown away by the disconnect between conservative policy proposals and the conditions in the community. “I distinctly remember two weeks post-residency, sitting down on the sofa and thinking, ‘I haven’t met a single patient for whom a health savings account will solve anything,’” he said, referencing a cornerstone of conservative health policy that allows people to put money aside tax-free to pay for medical services. He says it quickly became apparent to him that the state needed to get insurance to the poorest Alabamians and that sometimes the coverage would need to be free.

Waits and several partners set about opening a new clinic, one that would provide a full range of health services to an underserved community and would charge on a sliding scale based on patient income.5 Today, the staff of Cahaba provides mental health, primary, and pediatric care. Its staff also see patients at the county hospital’s nursing facility, labor and delivery, and inpatient units.

The clinic won Waits accolades around the state, including from the governor’s mansion. It also helped land him a spot on a task force that former Gov. Robert Bentley convened to find ways to improve access to health care in the state, with a focus on rural communities. “We’ve got unanimous resolution that it’s Medicaid,” Waits told me late last fall, before Bentley resigned because of a sex scandal. In a carefully worded report, the group suggested that the state “must move forward at the earliest opportunity to close Alabama’s health coverage gap.”

“Nothing happens without Medicaid,” Waits said. “It is the No. 1, the No. 2, it is the top 10 solutions.”

Years of work have also taught Waits that a functional system has to at least be able to provide preventive care for women and children. “It’s a whole nother thing trying to get the men in for their colonoscopies. But if the kids are getting in for their vaccines, kids are in school, teenagers aren’t pregnant, that’s kind of the backbone of the health care system.” But preventive care is also about things that happen outside a doctor’s office. Recent research has found that the risk of heart disease, even for those with family histories, decreases by half if people don’t smoke, get exercise at least once a week, eat healthy food and aren’t obese (even if they are overweight). But some of those are hard things to accomplish in the Black Belt. As was the case when Peterson was growing up in Thomaston, people must often travel long distances to reach a grocery store, which makes it hard to get fresh produce. As in many rural areas, there are few sidewalks in the Black Belt, and the hot weather during parts of the year is not conducive to exercise outside anyway. Waits counts lack of exercise as among the biggest barriers to health for people in the region.

Trust and access

And there are more intimate problems as well, such as communication between doctors and patients. “It definitely takes time, being a white doctor, for a black resident to trust you. To some extent that’s true everywhere, but it’s lengthier and deeper here,” Waits said. “Some of it relates to relatively recent medical ethics.”

Waits was referring to the notorious Tuskegee syphilis experiments, in which researchers deprived a group of black men with syphilis of treatment for some 40 years, until 1972, in order to study the progression of the disease. But that’s not the only cause of a documented lack of trust of medical professionals among African-Americans. Trust is a hard-to-measure but important aspect of how researchers gauge the ability of a provider to address a patient’s needs once she reaches a facility.

African-Americans are more likely to report being treated with disrespect by a doctor and are less likely to be health literate than whites, which can make it difficult to understand prescription drug labels or complete medical forms. And research shows that African-Americans do receive different treatment than whites. The 2015 National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality found that black Americans received worse care than whites on 41 percent of health care measures.

A doctor such as Remona Peterson, who is African-American and comes from the community, is likely to be a key part of the solution here. She said her whole reason for going to medical school was to take her intimate understanding of the area where her family has lived for more than a century and use it to improve her community’s health. The issues of trust and access hit home: Peterson remembers an aunt who was hypertensive and uninsured. She didn’t think any of the local doctors would see her, so she received little in the way of treatment. She had a stroke and died at age 54.

In some ways, Peterson’s winding path from straight-A student to rural doctor could help her adjust to working in such a challenging environment. Peterson hopes that she’ll be able to communicate more effectively with her patients and that they’ll trust that she cares. She also hopes she’ll be better at understanding their needs beyond physical and mental health. That could include making sure they have transportation to appointments or remembering to prescribe generic drugs people can afford. All of this could go a long way toward improving access to care. “If you grow up in this, you know what it’s like,” she said.

Peterson alternated between concern and excitement about what’s ahead. “I worry if I’m going to be good enough for them, for my people. I want to do my best; I want to be good enough.” She also described her ideal rural practice: a bus that can go and get patients, an office with a nutritionist, an exercise program, community health educators. She has high hopes for the future.

“There’s so much we could do in the Black Belt; I don’t even know where to start. I know what I can do as a doctor,” Peterson said, “but it’s going to take more than just me. It’s going to take a team of people who want to see the community change and get better.” Peterson will soon be part of that team. She will join the staff of the Greene County Health System on July 24.

[This story was originally published by FiveThirtyEight.]