The rapid reaction by Virginia Garcia's staff is emblematic of the innovative ways some health care providers and educators are responding to the dread many people in immigrant communities are experiencing during the first year of the Donald Trump administration. The administration's aggressive immigration enforcement policies are causing anxiety, hypervigilance and stress among many undocumented parents and their kids, who are often U.S. citizens by virtue of being born in the country. Some, for example, are suffering from depression and showing signs of post-traumatic stress disorder.

In response, health care workers are devising on-the-fly strategies they didn't learn in medical or nursing school to reassure patients frightened by Trump's tough immigration enforcement policies and harsh anti-immigrant rhetoric. Some educators and community groups are doing the same, helping arrange "know your rights" legal seminars for undocumented parents and developing educational materials for kids of people in the country without authorization to help them cope with the stress of their parents' legal status. At one Baltimore public charter school, more than 20 teachers and other staff members even volunteered to take in kids of undocumented parents if ICE agents were to detain their parents, and the students had no one else to care for them.

Health care workers and educators say they're employing these innovative strategies out of a sense of empathy and in order to provide the best care and education they can. Staff members at Virginia Garcia did not know whether the frightened woman or her child were undocumented – their immigration status was irrelevant to clinic workers providing the care patients come to the clinic for, says Kasi Woidyla, public relations officer for Virginia Garcia. About 55 percent of the 45,000 people Virginia Garcia serves annually are Latino. "We do not ask who is documented," she says. "We believe in common decency, and when our patients don't feel safe outside of our clinic, we will do what we can to calm those fears."

She noted that in September, ICE agents mistook a longtime county government worker, a Latino man, for an illegal immigrant. ICE agents briefly detained the man outside a courthouse near Portland where people were demonstrating against arrests of undocumented immigrants. "It was frightening, disturbing [and] humiliating, and I'm still trying to process being stopped because of my color and my race," Isidro Andrade-Tafolla told The Oregonian newspaper. Two agents alleged he was in the country illegally, he said, and had a photo on a cellphone of a man they purported to be him. Other ICE agents arrived, and one of them took a look at the photo and said he could go, Andrade-Tafolla said.

ICE officers and special agents conduct targeted enforcement operations every day to enforce 400 federal laws and statutes, says Danielle Bennett, an ICE spokeswoman. "During such operations, the officers and special agents may encounter and engage with individuals whom they ultimately determine are not intended arrest targets or possible witnesses," she says. "In this instance, our officers went to a specific location seeking a particular individual and interacted with someone they believed resembled our arrest target. It turned out the man was not the target, and no further action was taken." ICE's policy states that enforcement actions at sensitive locations, such as health care facilities, should generally be avoided, she says. Such actions require either prior approval from a supervisory official or exigent circumstances necessitating immediate action.

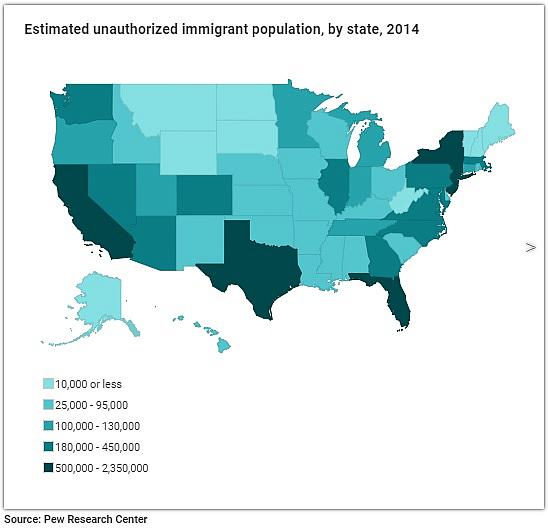

Encounters like the one involving Andrade-Tafolla have created widespread fear of public facilities among many immigrants, including of health care clinics. Many health care workers who provide care to immigrants have developed strategies for reassuring clients that they're safe at their facilities. Officials at a health clinic in a state with a significant immigrant population have worked out a plan in case ICE agents come to the facility. In such an event, clinic workers would ask to see a search or arrest warrant. Meanwhile, health care workers would shepherd vulnerable patients into nonpublic areas of the clinic. Officials at the clinic asked that the facility and its location not be named out of concern it could become an ICE target. ICE policy regarding places such as health clinics "provides that enforcement actions at sensitive locations should generally be avoided, and requires either prior approval from an appropriate supervisory official or exigent circumstances necessitating immediate action," Bennett says.

Some educators have also developed innovative strategies for helping kids of undocumented immigrants and their parents. Officials at Hamsptead Hill Academy, a public charter school in Baltimore, took several steps to help immigrant parents and their kids after an entire class of third graders broke down in anguish and terror on Jan. 19, the day before Trump's inauguration. The kids, most of whom are Latino, were terrified that Trump – who would be sworn in as president the next day – would deport them or their parents. Teachers and other Hampstead Hill staff members scrambled that day to calm the students as best they could.

Following the incident, Felicia German, the school's director of Latino outreach, took several steps to help ensure the well-being of immigrant students and the preparedness of Hampstead Hill's staff. She created a list of students who had been anguishing about the possibility that their parents would be deported and, in consultation with a Spanish-speaking mental health therapist who was working at the school, created a small group "for these kids in which they could have support if needed in dealing with these fears," German says. The group, comprised of third graders and led by the bilingual therapist, met weekly throughout the remainder of the school year. Kids could participate with their parents' approval. "It was a way to create a good follow-up for kids who were upset, in a safe space, with other kids from mixed families where the kids were expressing fears about their parents being deported," she says. "It was appropriately designed for 9 year olds."

German also arranged for teachers from Hampstead Hill and other area schools, plus staff members from local community groups, to obtain training on how to support kids feeling affected by the rancorous political climate around the issue of immigration. (Most of the kids at Hampstead Hill are U.S. citizens by virtue of being born in the country, though many of their parents are undocumented.) The training was provided by social workers from The Newcomer Project, a Baltimore public schools initiative that provides school and community-based resources for these students, and a representative from Johns Hopkins Centro SOL, which seeks to promote equity in health and opportunity for Latinos by advancing clinical care, research, advocacy and education.

The Newcomer Project developed written materials and exercises to help students from immigrant families cope with the anxiety and uncertainty of having a mother or father who might be taken away by ICE. In the "Taking Control Activity," students are shown two buckets on chart paper, one for "Things I Know or Can Control" and one for "Things I Don't Know or Can't Control." They're asked to put slips of paper describing their fears into one of the buckets and are coached that "we don't know that this will happen so we must put the fear aside in the 'I Don't Know' bucket."

German also helped create a Comité de Defensores, a group of about 60 parents who share information about ICE activities and keep each other up to date about rallies and marches to defend immigrants' rights. The group largely keeps in touch via a mobile app, WhatsApp. German also helps run a parents' support group, Conexiones Latinas, which promotes relationship building among immigrant parents, some of whom don't have many relatives in the U.S., so they won't feel isolated. A representative from CASA de Maryland, Inc., a nonprofit that advocates for immigrants' rights, visits the support group regularly to share updates on federal immigration policy. The group also aims to help immigrant parents build strong parenting skills.

Hampstead Hill was working to help undocumented parents of students before the incident in which the 22 third-graders melted down. Shortly before the inauguration, German had representatives from CASA de Maryland come to the school to train parents on how to create an action plan to provide for the care of their children if they are taken by ICE. The plan is a document that sets out who the parents want to take care of their kids if they're detained by ICE. Some worried about leaving their children with relatives who are also undocumented and therefore vulnerable to being arrested by ICE. German emailed fellow Hampstead Hill staffers, asking if anyone would be willing to take in a child who had no one else to care for him or her. More than 20 teachers and other staff members volunteered to provide a home to a child for 72 hours, regardless of the student's age or gender, German says.

Promoting programs to help the parents of undocumented students as well as helping their kids feel safe is part of Hampstead Hill's effort to provide a quality education, says Principal Matt Hornbeck. "We cannot imagine what a mother or father at risk for deportation is worried about in terms of their child's future," Hornbeck says. "If our school can provide any comfort or a sense of calm for them, it is morally imperative that we do so."

[This story was originally published by U.S. News.]