Health Insurance a Precarious Priority For Many Chicago Latinos

Sixty-seven percent of Hispanic women and seventy-five percent of Latino men in Chicago who work full time, were uninsured in 2009, according to an Hoy analysis. These figures were much lower than that recorded full-time workers whites, blacks and Asians. When the money is tight and your child is burning with fever, what to buy: medicine or food?

Although it has been over five years, Maria Garcia still remembers the night she had to choose between buying medicine for one of his six children or food.

Garcia, a native of Michoacan, came to Chicago in the 90's. For several years she did not know that her children, who were born in the United States qualified for coverage under AllKids, the health program established by the then governor, Rod Blagojevich.

So when one of her three daughters had a fever, had pain and needed to take ibuprofen, Garcia had to make a decision.

She chose the drug.

"I could not eat one day to buy medicine for my daughter," she said.

Choices such as Garcia are common among Latino parents, according to Horacio Esparza , Executive Director of Progress Center for Independent Living, a direct service organization in Forest Park for people with disabilities.

"If you have to pay $125 for youself to go to the doctor, they prefer not to go. But when you have a child as a parent, no matter what you have to do, take him to the doctor," said Esparza. "You spend a week's salary to see the doctor."

Garcia, who works six days a week as a waitress at a taqueria and lives in the Edgewater neighborhood, is uninsured.

About 65,000 Latinos across Chicago, who, like her, work at least 40 hours a week for 50 weeks a year, also lack health insurance.

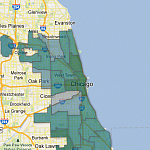

In fact, in the neighborhoods of Rogers Park, Edgewater and Uptown, only 50 percent of nearly 10,000 full-time Latino workers were uninsured in 2009, according a U.S. Census Bureau analysis for Hoy.

This uninsured rate is the lowest percentage compared to 11 similar areas with at least 7,500 workers, and among the lowest 10 percent of more than 550 areas in the country with the same characteristics.

The situation in Garcia's neighborhood is not an isolated case but part of a larger state and national trend involving full-time workers without health insurance.

Sixty-seven percent of Hispanic women and seventy-five percent of Latino men in Chicago who work full time, were uninsured in 2009, according to the analysis of Hoy. These figures were much lower than that recorded full-time white, black and Asian workers.

Not having health insurance requires workers like Garcia, to maintain a delicate balance between trying to satisfy needs and have adequate medical care for themselves and their families, while choosing between imperfect options.

These families try to meet every medical need with creative strategies like going to the emergency room at Cook County Hospital. Despite the impressive ingenuity, it has become a source of stress and has limited effectiveness.

"The reality is that this is very serious and sad, because many people have health problems that require ongoing treatment," said Aida Giachello, founder and director of the Center of the Midwest Latino Research, Training and Health Policy. "It's very sad because we have the resources and technology in our country. We have failed to share this with the general population, particularly with marginalized communities."

"It's a social injustice," said Giachello.

One of the most common strategies of this uninsured population is to ignore the problem because of high health care costs, according to Esparza.

"It used to work to eat," said Esparza. "Now we work to meet our health ... Many years ago someone consulted a doctor he was told 'Do not worry.' Now, everything is about money."

However, many workers do not have the money to pay their medical bills, so they just try to hold it together at work.

Michael Brito is one of them.

He was born in Morelos and came to America in 1995 to find work.

For 16 years he worked 60 hours a week in a Mexican shop lifting and moving heavy boxes like 50 pound beer containers.

Brown does not receive overtime pay and has never had health insurance.

Four years ago, he fell at work and hurt his arm. He could not move for one or two months. Finally, he went to see a doctor and was told he needed an operation.

His boss had initially said the company would cover his medical expenses. But then he changed his mind.

He began to say that the injury was not produced at work and that it happened because Brown was drunk.

Brito, who to date has not received physical therapy, still can not bend his arm completely.

Brown blames the law enforcement agencies who do not hold employers to account.

"There is much injustice," he said, adding that the leaders take advantage of him and other workers because they do not have insurance and do not know the law.

"Bosses abuse because they know we can not complain," he said. "There are too many workers and few job opportunities."

Just as there are employers who exploit workers, there are community members who do the opposite and cooperate to assist those who need medical care.

Garcia has been found on both sides of that support.

When faced with other health problems at home and with no money to buy medicine, a neighbor bought it for her.

She offered to pay it back but the neighbor refused to take the money.

On the other hand, Garcia once bought medicines for diabetes because her boss could not afford them. "She had no medication and I needed it. She asked for help and gave it." The woman and her partner help undocumented and do not have much money, Garcia said.

Garcia seeks to prevent health problems with a healthy lifestyle, says, pointing to a plate of fresh fruit on her kitchen table. She strives to eat healthily, exercise - walking a lot in her job as a waitress - and get seven hours sleep each night.

"I try not to get sick," she says.

Many of the residents who are sick and uninsured, have the option to pay cash for their treatment in pharmacies in the area such as Pharmac Mexi-care at 3200 W. 26th St. The owner, Jawad Hamdan, a Palestinian immigrant, was sanctioned by state inspectors for administering medicines to people without prescription. Hamdan said he no longer does this, however, maintains a list of needy clients who are not charged.

For those who do pay, going to a place like Mexi-care can be much faster and less expensive than going to to Cook County.

Other people go to health clinics as the Alivio Medical Center, a nationally recognized facility, founded by Carmen Velasquez, who cares for people regardless of their legal status or ability to pay.

On a recent weekday visit, the waiting room was crowded with people, many of whom had no health insurance or documents that verify their legal status in America. The clinical pharmacy, despite having fewer resources, are another option for people who need medicine, said Giachello.

And as a last resort, people come to Cook County Hospital.

"If there are no other options, they can go to Cook County," said Esther Sciammarella, executive director of the Hispanic Health Coalition of Chicago.

Garcia has been there when she has not been able to find a less expensive option. (She did not pay anything for receiving quarterly injections to relieve her foot pain.).

However, it has disadvantages.

Patients have to wait all day, she said, especially if they don't know English. "If people see you do not speak English, you have to return you to the end of the line," he said.

There are long lines because many people use the emergency room as primary care center.

Besides being much more expensive than preventive care, this type of emergency room use can divert resources away from those most in need, according Giachello.

And for people like Garcia, going to Cook County means having to take a whole day off of work - something that people in her situation can not afford.

When everything runs smoothly at home, Garcia is barely able to meet their needs for payment of rent and food, so to also then have to focus on health issues makes it more difficult.

This delicate balance is broken at the first sign of illness or injury.

This uncertainty gnaws and causes stress, she admitted.

Garcia is also concerned because her daughters are overweight. She knows that Latinos, according to several studies, are predisposed to diseases that may trigger diabetes.

Garcia is affiliated with Arise Workers' Center and has worked successfully, with other workers, to get employers to pay better salaries.

The center has not yet taken up the cause of health insurance, but Garcia said that once they take it up, they will achieve their goals.

However, she also expressed concern about her medical condition if there are massive cuts to Medicaid that Gov. Pat Quinn plans in the short term.

"If I don't have my Medicaid card, who knows what will happen," he said.

Octavio Lopez contributed to this story.

Methodology:

Hoy analyzed data from the American Community Survey 2009 to calculate the totals and the analysis of uninsured workers. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the data are based on a sample of the population, have a certain margin of error and should be considered estimates.

This story was originally published in Spanish at Vivelohoy.com.