On her own at 17, an Oakland student blossoms with love and support at school

Destiny Shabazz, 17, celebrates outside McClymonds High School after her graduation ceremony. She’s headed to Sacramento State University in the fall. (Lee Romney/KQED)

Destiny Shabazz grins as she opens the door to the West Oakland home where she rents a room. But she can’t show me -- a reporter -- inside. Her housemates like their privacy. She’s barely ever here anyway, Destiny explains, mostly just to sleep on an airbed inside a small converted office.

It’s early spring and Destiny’s walking to school. She’s got braces on her teeth and she’s sporting a pair of red sweats. She’s a senior and she’s got a lot on her mind. She’s determined to graduate and attend a four-year college.

“Yes, I’m excited to graduate!” she says. But her feelings are complicated. She searches for an Instagram post that resonates and reads it aloud.

“When you’re graduating but you’re scared to enter the real world 'cuz you cheated your way through all four years," she reads, and then laughs. “That’s, like, the story of me.”

School hasn’t been easy for her. Neither has life. Destiny is 17. She’s on her own, and that’s not unusual.

Destiny Shabazz, 17, at the West Oakland home where she rents a small room for $300 a month. (Lee Romney/KALW)

Unaccompanied youth are the fastest-growing group of homeless students in our nation’s schools. Among them are kids who run away from challenges at home, or cross the border into the United States on their own to escape hardship in their native countries. Others, like Destiny, fall through the cracks when their families are displaced.

Destiny’s not an adult. She’s not in foster care. And she’s not emancipated. But she is getting by — in some ways, thriving — thanks in part to some grownups at her school, McClymonds High School.

In fact, a handful of adults on this West Oakland campus are pretty much raising Destiny now.

At the end of the block Destiny points out the house she grew up in with her grandmother, who was her legal guardian. She sighs heavily.

“Well, we lost the house really because my grandmother passed away. But before she passed away we were struggling to pay the rent because it kept going up,” Destiny explains. The rent hikes, she says, kicked in when their elderly African-American landlord died and a series of corporate landlords took over.

Destiny’s grandmother received a rental subsidy through the federal program known as Section 8. That could have been passed down to Destiny’s brother when their grandma died in 2016, but “he was only 18 or 19. He couldn’t afford it,” Destiny says. “He’d just got outta high school.”

That brother bounces around now, couch-surfing with friends, essentially homeless. After he and Destiny were evicted, she moved to Pittsburg in the Bay Area for a while to stay with another brother and his family.

It didn’t work out. She says it wasn’t healthy for her there. Finding a place on her own was impossible. So Destiny reached out to a former neighbor, who converted her office into a small room. Now Destiny pays $300 a month to stay there.

“My grandma always taught me you can’t live somewhere for free, that’s not real,” she says. “People don’t just let you stay places.”

Being back in West Oakland feels right, though. Destiny grew up with a ton of kids here. They all call each other "cousin" now. She has strong memories of her childhood.

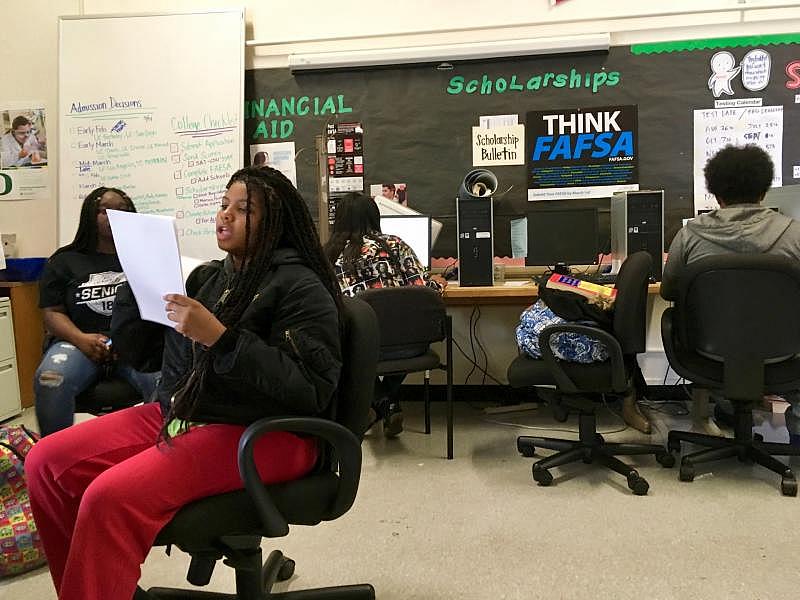

Destiny Shabazz, 17, works on scholarship applications at McClymonds High School’s College & Career Center. (Lee Romney/KQED)

“That Boys and Girls Club, there,” she notes. “I been going there since I was like 6 or 7.” She smiles, recalling all the field trips and good times.

Since Destiny’s been on her own, she’s been working really hard to boost her grades. She’s closing in on a 3.0 GPA. She has no first period this morning, but she’s headed to school early to work on scholarship applications.

When we get to McClymonds High, Destiny bumps into Devan McFadden, a staffer from the East Bay Consortium who runs the school’s college and career center with help from a district counselor. She’s excited to see him. She tells him she has just submitted her scholarship application to the East Bay College Fund, a couple of days before the deadline.

“Yes!! That’s what I like to hear,” McFadden answers.

Destiny follows McFadden into the center. It’s one of her main hangouts. One of Destiny’s best friends is here, too, bragging about her. She points out that Destiny just won a Rotary Club speech competition. And that she’s McClymonds' “No. 1 debater.” She even won a Bay Urban Debate League championship recently.

Right before the bell rings, Destiny finally settles down, and asks McFadden for help.

“OK, so Devan, I still don’t know what college I should be going to,” she says in a low voice, suddenly deflated.

“That’s fine,” he assures her. “You have to wait until you get your financial aid packages from them, to make your decision.”

Destiny’s recent spurt of hard work is paying off. By March, she’d already gotten into 20 schools. Most are historically black colleges, with a couple of backup state schools mixed in. Her financial aid is obviously really important.

In her AP English class today, the college and career staff take over to help. Oakland Unified School District college career readiness specialist Jamia Morton asks Destiny if she’s seen her financial aid offers.

Destiny’s worried. She hasn’t received them yet, she explains to Morton, because “they want to know, like, how am I a ward of the state, how am I independent?” The principal and vice principal are working on letters on Destiny’s behalf, as are several district staffers. Morton agrees to meet Destiny the following week to help her call each school and figure out exactly what they need.

Destiny Shabazz, 17, gets a hug from a front office administrator at West Oakland’s McClymonds High School. Destiny has no parent or legal guardian. She’s not in foster care, and she’s not emancipated. (Lee Romney/KQED)

Some students have to deal with parents breathing down their necks about college applications. Destiny has to motivate herself, but she has an army of adults helping to guide her through. Still, it’s complicated.

“My situation is, like, sticky, because I’m not emancipated,” Destiny explains after class. “I’m not in foster care, nothing,” she says. “So technically I’m like lost in the system.”

After her grandmother died, Destiny looked into the process of becoming emancipated through the courts. But it takes so long, she realized, she’d almost be 18 by the time she got through it. So she just lives in the gray zone.

“Sometimes,” she says, “if I have field trips, just so they won’t say nothing, I just sign my granny’s name. I just be like, ‘Whatever, they not even gonna notice.’ ”

Signing her dead grandmother’s name was tough on her emotionally, Destiny says. But it turns out plenty of people at school did notice that she was struggling. Destiny talks a lot about her Oakland Unified case manager, Miss Stacy. She’s more like a very involved aunt than a school bureaucrat. It was Miss Stacy — OUSD case manager Stacy Daniels — who helped her start collecting a modest government check. Destiny feels lucky.

“I always think, there’s people out there with way worse situations,” she tells me. “What if if you didn’t know what to do? What if Miss Stacy wouldn’t have helped me get my money? What would I have done?”

For a time after her grandmother’s death, Destiny says she felt really low. Shut down. She was isolating herself. She realized she needed her community. And she embraced her school life. Here at McClymonds, she’s social and ambitious. She runs track. She’s taking three college-level classes this semester. And she gets a stipend for her leadership roles with the debate team and the school’s Youth and Family Center.

And she’s also really resilient, considering 18 young people she knew have been killed. Last year, she says, just a week after a friend was shot to death, “two of my friends got murdered the same day, Travon and Peek a Boo. That shook me.”

The best friends had graduated from McClymonds, and Destiny said they were like big brothers to her. “That was all within a week,” she said of the three deaths. Their funerals were within a week, too. “Three funerals, three friends. All to gun violence.”

But here at McClymonds, the staff and administrators root for her. In the hall between classes, Brian McGhee, McClymonds High School program manager, says Destiny “speaks her truth” and is “an advocate for youth and students of Oakland.”

He sees her achieving great things in the political realm, so much so, he says, “when you say [East Bay Congresswoman] Barbara Lee, we say Destiny Shabazz, when we say Rosa Parks, we will say Destiny Shabazz. That’s the level I see her rising to.”

She’s not quite there yet though. McGhee calls her “a diamond in the rough ... I mean she got some things, we all got some things we want to work on. And we’re gonna support her.”

“I love the support,” Destiny says with a grin. “It never stops. Well, maybe in Algebra 2 class but then you know, it comes back right after.”

Algebra 2. That’s one of those things she has to work on. There was no permanent teacher for a chunk of the fall semester. Now it’s Mr. Tivol. And Destiny, well, she finds him condescending. He gets under her skin. The day before I come to school with her, she cussed him out. She was worried about today’s quiz. She apologized in an email. He wrote her back. He encouraged her. Told her not to “sweat it too hard.” But in class, it’s like Destiny can’t stop herself from messing with him.

She finishes her quiz early and takes out her iPad, even though that’s against the rules. When Mr. Tivol asks her to put it away, she refuses. So he calls in Will Blackwell, the school’s restorative practices facilitator.

Before Destiny leaves with him, she throws her quiz in the trash.

In the hallway, Mr. Blackwell talks to her straight. She knows perfectly well that she can’t use the iPad in class, he says. He tells her she doesn’t need to sabotage herself by being so combative.

Blackwell knows the students really well. That’s his job. When there’s trouble, he tries to bring the feuding sides together, to help them work it out. After they talk for a bit, he suggests a restorative justice advocate sit down with Mr. Tivol. For a group meeting like this, a student would usually bring a parent or some other adult advocate.

“All right now,” Blackwell tells her, “who do we call?”

It’s yet one more reminder of Destiny’s unusual situation. Destiny tells Blackwell that she’s “grown,” that she can be at the table by herself.

She can, Blackwell agrees. But he persuades her to seek adult backup. Her uncle can come, she says, him,and “Miss Stacy, too.”

He promises to schedule the sit-down in the next few weeks.

Later that afternoon, Destiny heads to the McClymonds Youth and Family Center. She spends a huge chunk of her life at this center. It’s staffed by a nonprofit called Alternatives in Action. And they show her a different kind of love. Destiny is honest about what happened in math class. It doesn’t go over well.

“You block your own blessings, you sabotage yourself, right?” Kharyshi Wiginton, then the community programs manager, tells Destiny. “At 17, I need that not to continue to be the story. This is bigger than this moment. In a second you’re not gonna have us. The world is not nice to adults like that. You’re not allowed to just mess up and mess up and mess up.”

The clock is ticking for Destiny, and the staff here is worried for her.

All the students at McClymonds call Wiginton “Miss K.” She buys Destiny dinner just about every evening. Destiny knows Miss K loves her.

“Everybody know[s] that I have two sides; like, I'm still a teenager,” Destiny says after the chaos dies down. She knows she has been through “things that make me act certain ways, you know, argumentative.”

Joining debate last fall has given her a way to channel her sharp tongue in a more productive way, she says, but, “I'm still growing.” It wouldn’t be real if the staff at the center didn’t rail on her for her mistakes, she says, “but they love me, too, you know — hard love, tough love.”

And thanks in part to them, Destiny has big dreams. She plans to return to Oakland and run for mayor in 2022. She has a vision for what her city needs.

“My plans are to change Oakland financially, socially and in equitability,” she explains. “I want Oakland to be like a black Wall Street. I want it to be black schools, black businesses, black courts, black teachers. I don’t want to stop the diversity,” she adds. “That’s not possible, but I know that Oakland is changing from Old Oakland to New Oakland, and the plan for New Oakland has nothing to do with black people.”

I check back in with Destiny at the end of the school year. She has chosen Cal State Sacramento, and she’s gotten four scholarships that’ll help with her first year. But she has a ton of catching up to do in Mr. Tivol’s class.

Still, Destiny pulls it off. On graduation day, I find her outside the auditorium, wolfing down a hamburger that Miss Stacy just brought her. She’s wearing stylish little shorts under her gown and high-heeled boots made of clear plastic. It’s a big day for her. But she’s had a major setback with her housing.

“I feel a little overwhelmed right now. I been real struggling,” she says. “I got kicked out of the house that I was at and now I’m moving around house to house for the last two weeks. It’s been hard.” Then she brightens. “But I’m good, because I’m graduating.”

The auditorium is packed. When the music starts and the grads take their seats, Destiny is hamming it up with her friends. And once the ceremony gets started, there’s a surprise for her — from the McClymonds High alumni association.

“You only have to hear her name to understand that there are bigger and better things for her,” the association president says in announcing a scholarship winner. “She will attend Sacramento State. ... She also played basketball, ran track, debated and was very active in the community.”

Before he even finishes, the crowd starts screaming Destiny’s name. And she’s up and out of her seat, doing a funky little dance on her way to the stage.

Everyone knows who he’s talking about.

“I might have been calling somebody else,” he tells her with a laugh. Destiny shrugs and responds: “I know.”

Destiny got a job at McDonald's. She turns 18 in August. It’s kind of scary. But Miss Stacy plans to stick by her, and a few other mentors have promised to make sure she gets through all four years of college with plenty of support.

[This story was originally published by KQED News.]