Highway Harms: In Virginia cities, rising health risks from interstate traffic

The story was originally published in Virginia Center for Investigative Journalism with support from our 2023 National Fellowship.

Urban geographer Johnny Finn points to majority Black neighborhoods whose inhabitants' health are negatively impacted by living near interstates and major roads.

Photo by Elizabeth McGowan // VCIJ at WHRO

This is the final story in a series about highway development through Virginia’s Black communities, and efforts to reconnect neighborhoods decimated generations earlier.

NORFOLK, Va.—On a Norfolk map, St. Paul’s Boulevard appears as a north-south arterial. But local urban geographer Johnny Finn views that same six-lane strip near Interstate 264 as a stark line of disparity.

Life expectancy is 85 years for people living downtown and in adjacent upscale, whiter west side neighborhoods, according to Finn’s research. It drops by more than two decades — to 61.5 — in poor majority-Black census tracts to the east dominated by three public housing complexes.

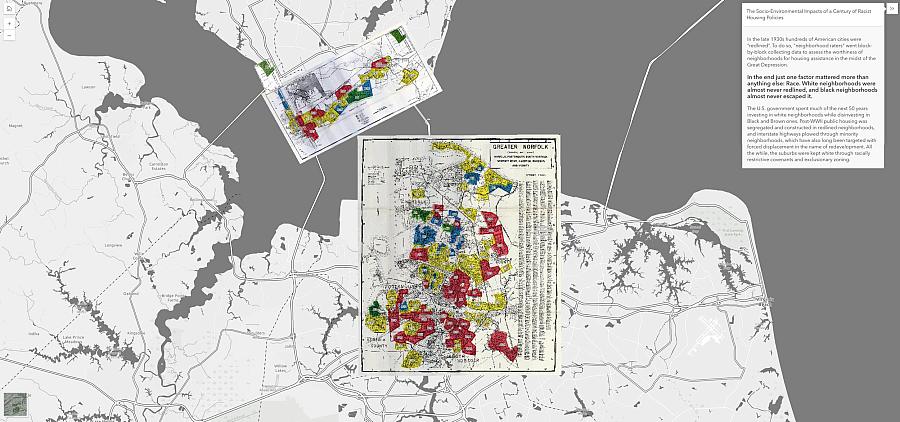

“This is the cumulative impact of a century of racist housing policies and practices,” said Finn, an associate professor at Christopher Newport University. He called the finding “one of the most shocking juxtapositions” in his study of southeastern Virginia, because it amounted to taking “literal years off of life.”

Finn’s findings, “Living Together/Living Apart,” reveals the socio-environmental impacts of racial segregation across Hampton Roads. The project mapped environmental injustices that plague neighborhoods where minority residents were systematically denied mortgages, insurance loans and other financial services based on their race or ethnicity.

Living Together/Living Apart, Christopher Newport University associate professor Johnny Finn

Highways intentionally ramrodded through these vulnerable communities only compound the environmental and health harms inflicted upon residents, Finn found.

Clean air and water, peace and quiet, shade trees, and comfortable housing – environmental factors degraded by close proximity to a highway – are among a long list of factors that affect health and determine whether people can thrive in the places they live, learn, work and play. Multiple other measures, including limited access to transportation and healthy food, also contribute to reduced quality of living.

“Taken together, they have a greater impact on health than medical care and individual lifestyle choices combined,” Finn said, paraphrasing a statement widely cited in public health literature. “The impacts of 20th century housing discrimination cascade and accumulate over time.”

Overwhelming evidence that health and quality of life are “socially determined” emerged in 2008 when the World Health Organization released a seminal report clarifying that earlier deaths and poor health in the United States and globally are not randomly distributed. Rather, they are directly related to cumulative life stresses of people left behind by society.

Follow-up studies revealed that these scourges could be minimized if countries addressed factors such as socioeconomic status, education, neighborhood and physical environment, employment, and social support networks, as well as access to health care. Unlike much of the developed world, the United States has been slow, or reluctant, to do so.

Interstate 95 bisects the Jackson Ward neighborhood in Richmond, Virginia.

Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WRHO

While highways that divide neighborhoods aren’t the sole cause of life expectancy disparities, they are a contributing factor. Interstate construction compounded discrimination and triggered a weakening of split communities, according to a 2020 Vanderbilt Law Review article by legal scholar Deborah Archer, “White Men's Roads through Black Men’s Homes.”

Highway planners “often targeted neighborhoods that were already struggling with racial discrimination and segregation, economic disinvestment, inadequate schools and deteriorating property values,” she wrote. Those impacts helped to entrench “the physical, psychological and economic division of communities.”

“The erection of highways between Black and White communities, or structures that encircled Black communities, sent a clear message of racial hierarchy,” Archer noted.

Virginia cities were a microcosm of racist highway and housing policies unfolding across the country, Finn said. Broadly, local rules, regulations and culture are a reflection of what occurs across the country, he added. Systems were set up to protect the interests of profits rather than those of the poor and marginalized.

For instance, urban renewal in Richmond, Norfolk, Alexandria and Charlottesville “often served as a guise to legitimize the forced removal of Black communities so that municipalities could repurpose these spaces,” Finn wrote in an Encyclopedia Virginia article on the topic. “Through urban renewal, vast swaths of American cities were remade to benefit the growing white middle class. Black communities in cities across America experienced disruption, dislocation, displacement, and a vicious cycle of urban disinvestment.”

With major redevelopment plans underway, Norfolk and Richmond leaders have a chance to improve living conditions for vulnerable communities along their busiest highway corridors.

Richmond, Norfolk attempt to heal divides

The environment-related health picture in low-income, Black neighborhoods is also startling in Richmond, roughly 100 miles northwest of Norfolk.

For instance, the lifespan of residents in Gilpin Court, a public housing complex in Jackson Ward, is 63 years, according to the Office of Health Equity at Virginia Commonwealth University. Just seven miles away, residents of affluent, majority-white Westover Hills can expect to live 20 years longer.

Gilpin Court is a public housing complex in the Jackson Ward neighborhood in Richmond, Virginia. The average life expectancy in the neighborhood situated beside I-95 is 63 years while residents of a primarily white neighborhood seven miles away is about 20 years longer.

Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WRHO

Fewer trees and abundant asphalt, brick and pavement mean summer afternoons are at least 5 degrees hotter in low-income Black communities in both Norfolk and Richmond, according to research by Groundwork USA, a Richmond nonprofit focused on access to green space. Asthma rates soar because of close proximity to highways and the particulate matter spewed by vehicle tailpipes.

However, what Richmond and Norfolk – two, similar-size cities with populations hovering near 230,000—also have in common is leadership willing to now acknowledge that past racist policies led to glaring inequalities that linger today. For instance, 20th century highways intentionally ruptured Black communities without the political power to fight back.

Both cities are attempting to heal those divides with Reconnecting Communities planning grants from the Biden administration.

In Jackson Ward, which includes Gilpin Court, Richmond is studying a proposal to cap Interstate 95 with an expansive, park-like lid. In the St. Paul’s neighborhood, Norfolk has plans to tame the spaghetti bowl affiliated with I-264.

The two cities are also in the midst of investing separate money to reimagine long-ignored public housing complexes isolated by construction of those same highway projects.

Reconciling those wrongs while reinventing a cleaner and greener future is a tricky, ever-evolving balancing act in urban centers across the country because of the rapid, turbulent and unpredictable onset of a warming planet caused by climate change.

Tailpipe pollution, hotter-than-average temperatures and relentless noise are some of the highway-related harms that have taken their toll on residents of the Jackson Ward and St. Paul’s neighborhoods.

Google Earth Image of the Tidewater Gardens area of downtown Norfolk.

Every day, about 149,000 vehicles speed past Jackson Ward on I-95 and adjoining I-64, and up to 101,000 vehicles navigate I-264 and adjacent roads through St. Paul’s, according to state Department of Transportation data.

“Climate change is making all of these existing problems worse, especially in communities of color,” said Richmond-based Dr. Michael Royster, senior vice president with the Institute for Public Health Innovation, which is dedicated to health equity and racial justice. “That’s why the issue is taking center stage in the public health community.”

The institute, with offices in Virginia, Maryland and Washington, D.C., is especially concerned about emerging infectious diseases and the health implications of heat as a warming planet spawns more-intense weather disasters that can jeopardize access to running water, electricity and emergency services in low-income communities.

Royster, a northern Virginia native and public health doctor for 25 years, said that even if the proposed “Reconnecting Jackson Ward” is presented as a potential remedy to past injustices, community “distrust of such initiatives is justifiable because it could worsen health outcomes.”

One path toward assuaging those fears is for local partners to put any proposal through a rigorous review, what the institute calls a health equity impact assessment, to identify and address risks that would likely burden those least able to cope.

Gardening: ‘Small form of reparations’

On a patch of land in Jackson Ward just north of I-95, Danielle Freeman-Jefferson teaches hands-on life lessons to local middle-schoolers who live in the adjacent public housing in Gilpin Court.

“Everything they grow, they try eating, even if it’s out of curiosity,” she said, referencing one class that pressed apricots into juice. “The kids have a ball.”

Freeman-Jefferson, a 24-year-old landscape architecture graduate with deep Richmond roots, co-manages the Charles S. Gilpin Court Community Farm for Kinfolk Community, one of multiple nonprofits overseeing gardens across the city.

She pairs tutorials that immerse students in soil health, plant biology, growing seasons, climate-adaptive gardening and harvesting techniques with sessions in art, history, reading, writing and comportment.

Though on the job just 18 months, she’s aware the garden exists at all because a neighbor, the late Lillie Estes, recognized the value of transforming a vacant lot that was a crime magnet into a peaceful and healing oasis seven years ago.

The neighborhood became an island surrounded by asphalt in the 1950s after the Richmond-Petersburg Turnpike Authority, a board approved and authorized by the state General Assembly greenlighted a six-lane expressway through Jackson Ward, even after city residents had thwarted numerous highway plans.

What later became I-95 not only displaced 7,000 residents but also escalated into a non-stop source of heat, noise, pollution and other ills.

“What we’re doing with this garden matters for a lot of reasons,” Freeman-Jefferson said about its restorative qualities. “It’s a small form of reparations and a way of taking land back after that highway was put in there.”

“These families are dealing with generational trauma, which can have effects on mental health. Having a garden to come to, eases that trauma.”

Students tend to an assortment of herbs and bushels of vegetables such as peppers, tomatoes, lettuce, okra, melons and squash. What their families don’t eat is delivered to community refrigerators and retirement homes.

“Having a garden can be a first step in connecting with nature and seeing value in yourself,” she said. “They see they can plant something, grow it and even feed a household.”

Tailpipe pollution shortens lives

Air pollutants from tailpipes include particulate matter, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas that traps heat in the atmosphere, and sulfur dioxide, a major component of diesel exhaust.

Also, nitrogen oxides and certain volatile organic compounds combine to form ground-level ozone, or smog.

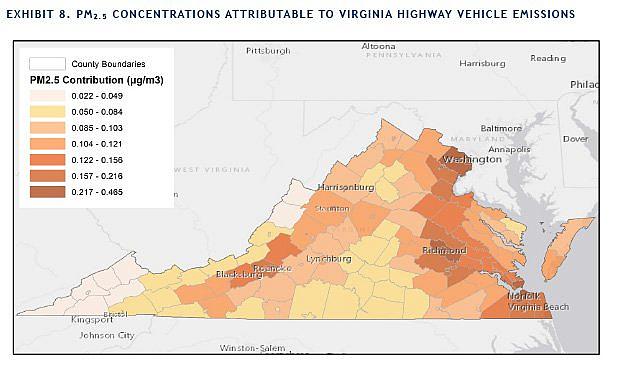

Particulate matter—especially PM 2.5, fine particles less than one-tenth the diameter of a human hair—are associated with the largest number of health problems because they are tiny enough to imbed in lung tissue and enter the bloodstream. Exposure is linked to asthma and other respiratory diseases, and a wide range of cardiovascular issues, including blockage of blood vessels, high blood pressure and strokes.

That awareness prompted doctors statewide to form Virginia Clinicians for Climate Action in 2017. One of the organization’s early campaigns pushed the General Assembly to pass Clean Cars legislation in 2021 to accelerate drivers’ access to electric vehicles.

Statewide, concentrations of fine particulate matter were expected to contribute to 3,000 premature deaths, 3,600 hospitalizations and 1,600 emergency room visits annually, according to a report the clinicians issued in late 2020.

An Assessment of the Health Burden of Ambient PM2.5 Concentrations in Virginia prepared for the Energy Foundation and Virginia Clinicians for Climate Action.

That same report revealed that Norfolk and Richmond, along with northern Virginia, led the state with the highest concentrations of PM 2.5 emitted by traffic traveling on state roadways. Other problem areas, though less severe, are in Roanoke and along the I-85 corridor in western Virginia.

“Our goal is to advance climate solutions because they are health solutions,” said Dr. Neelu Tummala, an ear, nose and throat surgeon in Northern Virginia who belongs to the advocacy group. “We’re thinking about source control, which means addressing the root causes.”

Air pollutants can cause disparate harm to communities living near highways. That’s why it’s crucial that physicians tune into their patients’ backgrounds and where they live, Tummala said.

Indeed, asthma affected at least 15% of the people living east of St. Paul Boulevard in Norfolk, according to Finn’s research.

Neighborhoods redlined a century ago share the same economic and health problems, Finn said. “Today, (they) have the highest uninsured rates, highest rates of asthma and diabetes, and the lowest life expectancy.”

Can a park atop I-95 cool Jackson Ward?

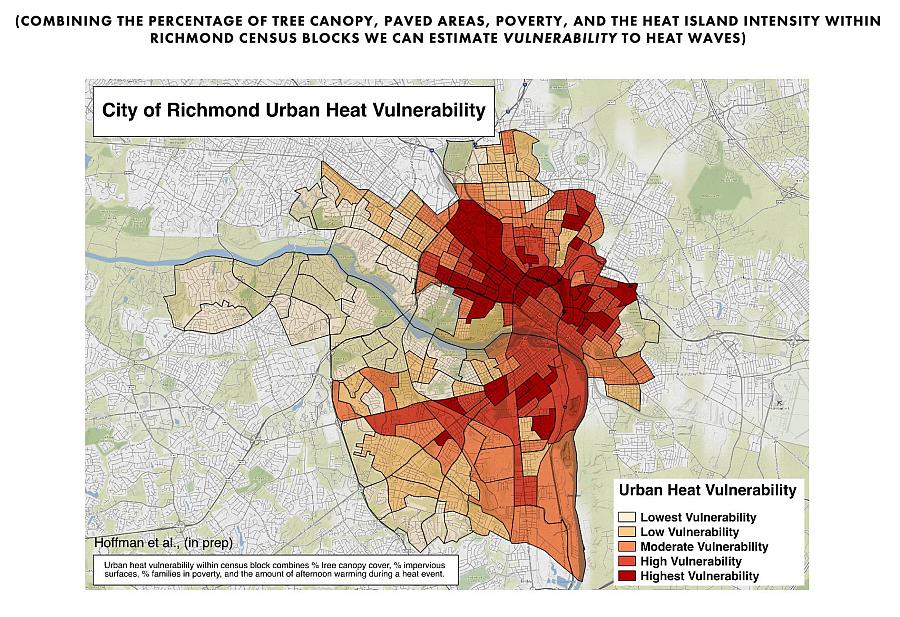

A warming city prompted Jeremy Hoffman, the Richmond-based director of climate justice and impact at Groundwork USA, to study what’s called the urban heat island effect. Temperatures in cities are consistently higher than rural settings because the asphalt, concrete and bricks of roads, buildings and other infrastructure absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than forests, meadows and other natural landscapes.

A July 2017 heat wave in Richmond fueled Hoffman’s curiosity. Teams of community organizers and volunteer scientists collected 60,000 temperature readings citywide on July 13.

Parts of Jackson Ward and other lower-income and minority neighborhoods were much warmer than those with plenty of shade from tree cover and other vegetation. In fact, data revealed some parts of the neighborhood were 16-degrees hotter than shaded communities during the extreme weather.

Jeremy Hoffman, Groundwork USA.

Follow-up research begun in 2021 produced heat island maps in nine other Virginia cities and 60 cities nationwide that mirrored results in Richmond. Neighborhoods historically and systematically denied access to wealth are hotter, Hoffman said.

He is encouraged by Richmond’s plan to reconnect Jackson Ward. Covering part of the highway that divided it decades ago with a green lid that could provide up to five acres of park space.

“Undoubtedly the Interstate 95 cap would lower temperatures, especially if designed to do that specifically,” he said.

Heat islands are more dangerous when the air is polluted with exhaust fumes, said Tummala, the doctor. That combination can affect people’s physical and mental health because it prompts them to stay inside instead of heading outdoors to exercise.

“To stay in shape, we tell people to go outside,” she said. “When they can’t, it’s often contributing to their anxiety. It’s really challenging.”

‘Traffic noise is a constant stressor’

Traffic zips along I-95 in Richmond. The interstate bisects the Jackson Ward neighborhood.

Photo by Christopher Tyree // VCIJ at WRHO

Ear-piercing sirens, horns, tires slapping pavement, revving motorcycles and roaring semi-truck diesel engines are all part of the daily cacophony in Jackson Ward along I-95 and in the St. Paul’s neighborhood surrounded by I-264.

Nationwide studies show that exposure to road traffic noise is highest in minority and low-income communities torn asunder by developers seeking the path of least political resistance, according to research published in 2021 by the American Public Health Association (APHA).

Residents might brush the din off as merely annoying. However, Jamie Banks, who chairs APHA’s Noise and Health Committee, said the impacts are harsh.

“Traffic noise is a constant stressor,” Banks said. “Your brain is telling you that you don’t hear it. But your body is hearing it and releasing cortisol and other stress hormones, which leads to a cascade of reactions.”

Those reactions can include interrupted sleep, and increases in cholesterol, blood sugar, blood pressure and anxiety levels. They can put people at risk for diabetes, strokes and cardiovascular disease.

“People in poor health are more susceptible,” she said, adding that those in low-income communities fall into that category due to a lack of access to doctors, healthy food and exercise spaces. “This is critical.”

Banks, based in Maine, also serves as the president of Quiet Communities, a nonprofit trying to reduce harmful noise and related pollution.

“We knew way back in 1968 that noise pollution caused adverse effects,” Banks said, referencing a U.S. Surgeon General report. “But nothing was done for decades and now we’re so far behind.”

Steve Haas, the CEO of SH Acoustics in Connecticut, said a park-like cap over I-95 in Jackson Ward could indeed dampen traffic sounds inside the “tunnel” if the structure is designed to dampen vibrations. Otherwise, big trucks could sound even louder.

“Overall, the idea of a cap seems good, but to not think about noise and vibration issues would be shortsighted,” Haas said.

Solutions aren’t as straightforward in Norfolk, where plans to calm and redirect traffic at interchanges, ramps and an overpass linked with I-264 are still in early stages.

Overall, noise levels in a majority of the now-razed Tidewater Gardens apartments near the highway were categorized as “normally unacceptable,” according to a U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department analysis. Norfolk received a federal grant to redevelop the site into new homes, apartments and shops.

To mitigate the highway racket, Norfolk could pave roads with specially mixed materials that reduce tire noise, keep roadways clear of potholes and cracks, install barriers that swallow or redirect sound and prohibit the use of notoriously loud engine brakes on semi-trucks, said Haas, who is not involved in either project.

Haas emphasized that the separation of homes, schools, other buildings and public spaces from roadways can play a huge role in mitigating noise.

“Buildings need to be insulated and have better facades, doors and windows, so noise doesn’t penetrate like a hot knife through butter,” he said. “But people also need to be able to leave their houses without being impacted by noise.”

However, the first step to noise mitigation isn’t as simple as a speed bump. Instead, it’s getting the right people to care enough to act.

“Too few people pay attention to noise because you can’t see it, touch it or hold it,” Haas said. “The champions of these projects have to realize that everyone can have a healthier lifestyle if this is addressed.”