Hill flounders on kids’ care

Rebecca Adams reported this story with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being, a program of the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism.

A girl is examined by a physician’s assistant in Aurora, Colo. (John Moore/Getty Images)

Minnesota officials knew they would exhaust Children’s Health Insurance Program money by the end of this year. Then they discovered the news was worse: The state would likely be out of money for coverage of low-income children and pregnant women by the end of September. And it became increasingly clear that Congress was probably not going to meet a deadline to help.

The state will have “to take extraordinary measures to ensure that coverage continues beyond October 1, 2017, if Congress does not act,” warned Minnesota Department of Human Services Commissioner Emily Piper in a Sept. 13 letter pleading with lawmakers for “urgent” action.

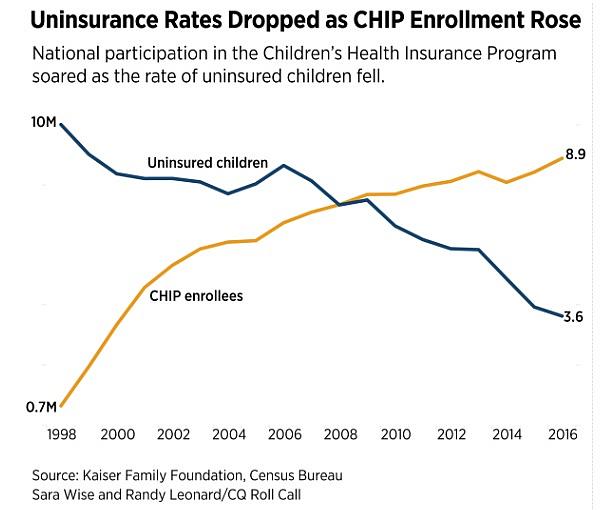

Minnesota is the first state to hit a funding crisis, but others are on the cusp. Nine other states are projected to face a shortfall by the end of the year because Congress has not yet acted to renew federal funding for the 8.9 million children and women served by CHIP. That funding expires Sept. 30.

States can use two-thirds of any leftover money until it’s gone, leading some lawmakers to suggest that the deadline is not a hard one. But state officials around the country, including those whose funds are expected to last until the spring, are preparing notices to send to families in the coming weeks to warn them their coverage could disappear.

By late March, 32 states would likely drain their money, according to separate projections by the nonpartisan Kaiser Family Foundation and the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. All states would do so at some point in fiscal 2018, according to the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

“It’s really important,” said Cate Arnquist, an Arizona schoolteacher who recently got coverage for her 8-year-old son through the state’s CHIP program, known as KidsCare. “For me, I hope I only need this support for a limited time but lots of families need it even more than I do. If we really value our future, which is our kids, we need to take care of their health.”

This week’s deadline is hardly a surprise — Congress set it two years ago. That a program broadly supported by both parties could now be on the brink of a crisis for lack of action underscores not only the dysfunction in Congress, but also how children’s coverage is often an afterthought in Washington.

Oregon Health Authority Acting Director Patrick Allen — from the home state of both the Senate Finance Committee’s top Democrat, Ron Wyden, and House Energy and Commerce Chairman Greg Walden, the two panels that oversee CHIP — called the renewal of the program’s funding “near the top of the list” of federal priorities for the state.

“It’d be extraordinarily helpful to kids in Oregon and in all states if Congress could stick to getting its basic work done,” said Allen. “This is not complicated. It’s not breaking new ground. This is a reauthorization of a policy that enjoys universal support. This ought to be the easy stuff.”

States are already investing in planning for a funding gap, and consumers are justified in worrying about what will happen, says the assistant commissioner for health care at the Minnesota Department of Human Services, Nathan Moracco.

“Whether they fix this eventually or not, in many ways the damage is already done,” said Moracco. “It’s put this group of people at risk. It’s unfortunate that they’re even in that position of having to worry about whether they’re going to have coverage and it’s put us in a position of how to come up with funds that a month ago, we had no reason to believe was at risk.”

On Sept. 18, the Senate Finance Committee began to break the congressional inertia by releasing a bill that would resolve the issue for five years. State officials and children’s advocates, relieved to finally have a bipartisan agreement in at least one chamber, praised it even though it would scale back federal contributions to the states after two years.

But Senate leaders have not said whether they would bypass a committee vote and when they would consider it on the floor. The Finance Committee’s single hearing on children’s coverage was delayed from May until September because of rancor over the Democrats’ 2010 health care law and Republican efforts to repeal parts of it. A floor debate on CHIP has the potential to become entangled in similar political quarrels.

The House has made no public progress on CHIP this year except to hold one subcommittee hearing in June, which was dominated by partisan sparring over the GOP repeal legislation. Behind-the-scenes talks between the parties have splintered over issues such as how to pay for the funding.

State officials and children’s advocates say that lawmakers’ inability to pass legislation as bipartisan and basic as a children’s health insurance renewal on time will have consequences for consumers. CHIP was instrumental in boosting the share of children nationwide who have coverage from 86 percent in 1997, the year Congress enacted it, to 95 percent of U.S. children today.

If Congress fails to extend CHIP, about 1.1 million people in the program could lose coverage completely, according to a study for the Commonwealth Fund by George Washington University professor Sara Rosenbaum, who also chaired the Medicaid access commission until earlier this year. Many others could face scaled-back coverage and significantly higher out-of-pocket costs, which could discourage people from getting or staying covered, and states would have to find more money as federal contributions fall.

“It would be a shame if Congress failed to act on a program that it doesn’t seem anyone disagrees about,” said Allen of Oregon. “Getting the president and Congress to act in a timely way would be helpful.”

Overshadowed by repeal efforts

The 8.9 million people the program covers is nearly as many as the 10.3 million people that CMS said were covered earlier this year through the marketplaces established by the 2010 health care law.

But the health care law exchanges get far more attention.

Lawmakers blame this year’s chaotic legislative fights over the law as the primary reason they have been distracted from passing routine, bipartisan updates to existing health care programs that are expiring and must be renewed in order to function.

Congress also flirted with missing the deadline for reauthorizing Food and Drug Administration user fees, which comprise $2 billion of the agency’s $5 billion budget. That deadline also was Sept. 30, although an informal, self-imposed target was July so the agency would avoid a last-minute crisis.

The Senate cleared the legislation — with only minor changes to the deal the industry and the agency brokered 18 months earlier and formally sent to lawmakers eight months before the vote — on Aug. 3 by 94-1. The House had passed it July 12 by a unanimous voice vote.

Other programs that are still waiting to be renewed, along with children’s insurance, include health centers, teaching hospitals, the National Health Service Corps, a pregnant women and new mother home visitation program, Medicaid reimbursements for safety net hospitals, aid to Puerto Rico’s Medicaid plan and a variety of Medicare payments.

Even if all of those programs are updated shortly before the deadline hits, the delays raise questions about whether Congress is essentially creating problems rather than solving them by waiting so late to provide certainty to all of the people and institutions depending on these systems.

“It surprises me that it’s come down to the wire like this,” said Cathy Caldwell, director of the Bureau of Children’s Health Insurance in Alabama. “We’ve been talking about the need for continuing funding for at least a year now, certainly with the anticipation that it’d get done before this point. What we’re asking for is a straight extension.”

She added that in conversations she has around the country with other state officials, “we’re just assuming there’s been so many distractions with other things going on that the continuation of CHIP just hasn’t gotten the attention it needs yet.”

Alabama’s contingency plan calls for sending warnings to families as early as October if Congress does not act, even though the state would not exhaust its funding until March. But if it expects to have to remove enrolled children, Caldwell said officials need to inform families and begin the cumbersome process of changing its systems soon.

Unless state officials get “absolute assurances” that funding is on the way, Caldwell said, they will have to start thinking about denying coverage to some children when they apply in October to renew their benefits.

“We’d try to hold off,” Caldwell said. “But, ideally, if we really had to close the program down, we would need to start as soon as possible.”

Federal lawmakers say they are doing their best in a year fraught with tensions over the direction of the country, an ambitious agenda, an unpredictable electorate and a nascent presidency that Republicans want to use to reshape the federal government’s role in Americans’ lives.

The partisan health care debate continues to consume Congress. House lawmakers also blame the Senate for falling short so far of the GOP’s campaign promise to overturn the 2010 health care law, exacerbating tensions within the party.

“It certainly was true that the Senate’s failure to act escalated [problems in] a number of health care areas,” said House Ways and Means Chairman Kevin Brady, whose panel does not oversee CHIP but handles other health issues including Medicare and the health care law.

“We could have done it earlier,” acknowledged Energy and Commerce member and former chairman Joe L. Barton of the CHIP renewal. “It’s biblically miraculous when the Senate acts.”

The Senate Finance Committee — which has produced a bill, unlike the Energy and Commerce Committee — also has several time-consuming issues on its agenda, including a tax overhaul and other unresolved health care changes. The panel is wading back into the contentious arena of the health care repeal debate with a Sept. 25 hearing on a last-ditch effort by Sens. Lindsey Graham and Bill Cassidy to overturn the law by Sept. 30. That’s when an opportunity to pass a repeal with only a majority of votes instead of 60 will vanish.

Finance also is one of two Senate panels that had been considering whether to pass legislation to stabilize the health care marketplaces. Some insurance companies plan to abandon the exchanges and other insurers requested high premium increases for 2018 in large part because of confusion about what Washington will do about the law or payments to insurance plans.

At least one lawmaker is so focused on the health repeal debate that he seemed unaware of the failure to renew CHIP. Cassidy, a Finance member whose repeal bill is complicating consideration of the children’s health bill, mistakenly told CNN on Sept. 20 of the program: “It was just reauthorized.”

Cassidy touted the children’s health program as a model, noting that his repeal bill proposes to run block grant funding for other insurance through CHIP.

“There’s nobody who criticized the CHIP program,” Cassidy said. “They all think it works.”

A crowded calendar, fallout from the lingering and bitter repeal debate, and a lack of focus could cause Congress to trip over the Sept. 30 deadline for CHIP and other programs.

Governors say lawmakers should understand how vital the children’s program is. Utah GOP Gov. Gary Herbert praised the bipartisan efforts to renew CHIP by Finance Chairman Orrin G. Hatch, who created the program in 1997 with then-Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, but expressed concern that Congress has not cleared the new funding.

“Our most vulnerable children and their families depend on CHIP for cost-saving pediatric care, and the state of Utah needs the certainty of ongoing support for CHIP in order to budget appropriately for the near term,” said Herbert in a comment for CQ.

A proposed plan

Congress is at risk of missing a CHIP funding deadline for only the second time in the two-decade history of the program. A previous two-month lapse came during the George W. Bush administration when Republicans and Democrats disagreed about whether to expand children’s coverage.

To be sure, the Senate plan provides a blueprint as House lawmakers try to write bipartisan legislation before the deadline.

The Finance proposal would keep a 23-percentage-point payment increase for states that was in previous laws for two years, buying states some time to plan. That’s important, since surveys show almost every state counted on that funding. In a state like Texas, the state legislature is scheduled to meet only every two years.

The bill would also allow states some wiggle room to escape the requirement to maintain coverage. States that have expanded coverage to families earning more than three times the poverty level could trim coverage if officials wanted. Currently, 19 states are in that category. None have publicly committed to reducing eligibility if Congress gives them that power, but the flexibility was philosophically important to Republicans.

Walden told CQ before the House left for its weeklong recess Sept. 14 that House lawmakers are close to a bipartisan agreement.

“We still have some things to work through, which we’ll do at the staff level and member level next week when we’re out, and then I hope when we return we’ll have an opportunity then to mark up,” said Walden.

If the panel does hold a markup meeting to approve a bill this week, a session that the committee has not yet announced, that would leave at most only two or three legislative days after the markup to clear it before the deadline hits.

Consequences for children

There are complicated consequences if the funding deadline lapses.

If Congress were to take longer than a couple of weeks beyond the deadline to renew the program, some states plan to take steps toward capping enrollment or shutting off coverage entirely.

The states are split between those allowed under current law to stop covering kids and those that are not.

Every state would also face the hassle and costs of preparing for changes and training their staffs. Colorado, for instance, estimates that it would spend $300,000 on those costs, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Most states do have budget cushions that would protect their programs for at least another month or two. But states are already spending their money and energy making contingency plans in case Congress does not act. Some states may hold back on the normal outreach efforts they use to let residents know about the program and encourage them to sign up.

And parts of CHIP would halt completely Sept. 30. For instance, states would lose the ability to expedite enrollment or the renewal of a child’s benefits in CHIP by using information from other programs such as State Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Medicaid or the food stamp benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program.

That so-called “express lane” process has helped kids get covered without delays. The Georgetown Center for Children and Families cites an evaluation of the flexibility that shows it offers administrative savings and reduced barriers to coverage.

Impact in different states

The children in Minnesota are in a better position than those in some other states. They are in the type of program that is not allowed, under the 2010 health care law, to cut back eligibility until 2019. The law protects Medicaid programs and states that used their existing Medicaid programs to create CHIP, banning those states from changing eligibility policies and cutting off children until 2019.

But those states will have to come up with more money.

The law would allow the state to stop covering pregnant women, an option Moracco of Minnesota doesn’t want to think about.

“Think about pregnant moms and how important prenatal and postnatal care is for our young population and starting out their lives as healthy babies,” he said. “We’re talking about the success of being able to deliver healthy babies and pregnant mothers receiving the care we want them to receive. It’s such a vital program.”

But the state’s options are limited. “We need some kind of action by the federal government or our own state government or we may just be in the position of having to stop eligibility,” Moracco said.

States are divided into three categories: those that cover CHIP kids through their Medicaid programs, those that created separate CHIP programs and those that use a combination of those approaches. Families would be affected differently depending on what type of system their state uses.

People in states with separate CHIP programs are at risk of not being able to get covered if funds run out. Those states are allowed to cap enrollment, as states such as Arizona, Alabama and others did in the past.

After Arizona effectively ended its CHIP program, its uninsured rate for children became the third-highest in the nation and was almost double the national average. The number of Arizona children and women covered by CHIP, known in that state as KidsCare, nose-dived from 45,000 in 2010 to about 1,000 in 2016 before the state restored the program.

If families in those states that can freeze enrollment lose coverage, they might be able to turn to the health care law exchanges for coverage if their income is between the federal poverty level and four times the poverty level.

But the benefits of the 2010 health care law are not as generous for children. During the Obama administration, HHS was supposed to certify any exchange plans that are as good as CHIP, but officials decided there weren’t any.

Lawmakers essentially would be turning families away from a highly regarded program and into (for those who qualify) the very health care exchanges Republicans deride as inadequate and harmful. In five states this year, consumers had only one insurance company to choose from — a point that critics cite as evidence of the failure of the 2010 health care law.

And if they aren’t eligible for marketplace insurance or can’t afford to buy it on their own, families might end up with no coverage at all.

Families in states that expanded their Medicaid programs to include the CHIP population when they created the children’s health program must maintain eligibility until Sept. 30, 2019, but their reimbursements for the CHIP children will decline to far less generous Medicaid payment levels.

That would be an even bigger burden than usual this year because two recent federal laws boosted the share of CHIP payments that the federal government gives states. Traditionally, states had picked up about 29 percent of costs on average for CHIP while the federal government paid for about 71 percent of costs. Each state’s precise matching rate varies and is based on a formula.

But the 2010 health care law and a separate 2015 law renewing CHIP funding required the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to pay the more generous matching rate that added 23 percentage points to each state’s payments in their rate. Currently, 13 states including Arizona, Georgia, Kentucky, South Carolina and Utah, don’t pay a dime toward CHIP, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The federal government pays it all.

If the funding deadline passes, states that use Medicaid for their CHIP program would see their money from the federal government plummet and their own required contributions climb. For instance, Minnesota’s share of CHIP costs would go from 12 percent of total costs to 50 percent.

States that used a combination approach — expanding Medicaid for some CHIP kids but creating a separate program for others — could treat those populations differently.

In Alabama, which has that type of system, families would be treated differently based on which group they were in. Those that qualify under the Medicaid branch of the program would be able to get benefits although the federal government would pay the state far less for them. Children in low-income families with slightly higher income who are in the separate CHIP program, known as ALL Kids, would be denied.

For families, the delay causes anxiety.

Arizona is the most likely state to cap enrollment, policy experts say.

A state law requires the state to immediately stop processing all new applications if Congress passes legislation, such as the Finance bill, that would reduce Arizona’s matching rate. The state also would freeze enrollment if funding runs out.

Children’s advocates in the state, such as the Children’s Action Alliance, say they could accept the Finance deal because it would give them two years to lobby for changes in the state law.

At this point, the main message from state officials in both parties is simple: Do something.

Enrollees are facing a real loss of coverage, said Minnesota’s Moracco.

“It’s a real deadline,” he said. “I’m not sure how this could be portrayed as not an emergency.”

[This story was originally published by Roll Call.]