How 3 big Southern California hospitals are dealing with their growing number of ER visitors

This story was reported in partnership with the California Data Fellowship, a program of USC’s Center for Health Journalism. Staff writer Ian Wheeler and staff photographer David Crane contributed to this report.

Other stories in the series include:

Southern California ERs look for answers to the crush of newly insured patients at their doors

Southern California emergency room use has actually risen after the passage of Obamacare

Kaiser Fontana and Kaiser Ontario have the highest emergency departments visits in California, according to state data which combined their visits.(Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

Third in a four-part series that examines emergency room use in Southern California.

Emergency departments at three hospitals stood out in all of California as the ones that were the most visited in 2016.

They couldn’t be more different.

Kaiser Fontana and Ontario

For Dr. Alp Arkun, the emergency department of the future goes back to the past, when heart attacks, falls, broken bones and traffic accidents made up the bulk of patients who were rushed through the doors, and physicians spent their time on the fast, life saving practices they were taught.

Dr. Alp Arkun, Chief of Emergency Medicine at Kaiser Permanente in Fontana, CA. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

“We’re seeing a lot preventative visits if you will, not necessarily, ‘hey take care of my high blood pressure,’ but they may be here for something else and we discover they have high blood pressure and we recommend something,” said Arkun, Chief of Service of Kaiser Emergency Department at Fontana and Ontario.

“I can tell you, the types of patients didn’t change,” he added, “the volume did.”

In San Bernardino County, a region that has seen growth in both population and the number of people gain health insurance, Kaiser Fontana and Kaiser Ontario have the highest emergency departments visits in California, according to state data which combined their visits.

In 2010, Kaiser Fontana had 87,316 visits to their emergency department. In 2016, that number increased by 65 percent to 143,783 visits, having added totals from Kaiser’s new Ontario facility, which opened in 2011.

At the same time, nearby Arrowhead Medical Center, a public hospital in Colton run by the San Bernardino County, saw a 27 percent decline in emergency room visits, from 127,257 in 2010 to 93,283 in 2016.

But unlike many medical facilities, Kaiser was ready for the boost in membership, Arkun said.

Dr. Alp Arkun, chief of emergency medicine at Kaiser Fontana. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

“We had a huge onboarding of physicians and nurses and staff and I think the organization was prepared pretty well for the onslaught of new membership.

What also increased in the emergency department was the number of nonmembers, Arkun said.

“We have the highest non-member rate,” he added.

Indeed, 40 percent of visitors to Kaiser Fontana’s emergency room in 2016 were non-members. In Ontario, non-members made up about 20 percent of emergency department visits.

Arkun said the increased visits likely stressed the entire health care system across San Bernardino County, including the other hospitals in the area. Patients still received care, he noted, and the number of uninsured patients fell as well.

But in general, San Bernardino County’s challenge is having enough primary care physicians.

“When you have new insurance and you can’t get to a physician and you can’t get to primary care, you’re going to go the emergency departments,” Arkun said. “It’s a lot of what we were seeing before. Patients are seeking care more, fortunately and more easily with the ACA.

Before they wouldn’t come to the ED unless things were really bad.”

The overall health system is getting taxed and all emergency departments are finding themselves making difficult choices, because everything is about resources, Arkun said.

“Everybody has finite resources,” he said. “We try our best to help the sickest first.”

Which is why the emergency department of the future needs a rewind.

“Ideally, the emergency department of the future will go back to focusing on emergency care and less on primary care but that’s not going to happen because we will it to,” Arkun said. “That’s going to happen if we get the primary care resources in the community to talk care of those patients.”

Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center

Near downtown Los Angeles, one of the busiest emergency departments in the nation takes in some of the area’s most severe injuries: Gang-related gunshot wounds, burns, injuries from multi-vehicle crashes on busy freeways nearby.

The assignment chart at one of the emergency rooms at County USC, one of the busiest in the state. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

Those are just some of the cases rushed through the doors of Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center’s emergency department.

In addition, when despair is high and there is no other place to go, those from Skid Row and people from immigrant communities also come to the hospital, once nicknamed the “Great Stone Mother,” because of its size and art deco style.

With nearly 130,000 visits to its emergency department in 2016, the hospital nearly topped the state.

Still, even after the Affordable Care Act passed, LAC+USC saw fewer visitors compared to 2010.

“I completely expected the increase because of an unmet need,” said Dr. Michael Menchine, an emergency physician at County-USC Medical Center and an associate professor at USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

“We’ll see the drop in emergency department visits, but I honestly think that’s a decade away,” he said. “The local clinics have to increase their capabilities. The patients need to know where they are. It’s not exactly obvious where the primary care doctors are in the community, whether they are trustworthy.

“Our hospital is a very well trusted institution in our community.”

The hospital sees a high number of both Medi-Cal patients and uninsured. At least 2.9 million people statewide remain uninsured, according to the California Health Care Foundation.

Many of them are undocumented people who do not qualify for federal or state subsidized health insurance. Los Angeles County offers some local, subsidized care for them.

“Again, it’s just one of those things that the uninsured have the same fears of being stuck with a big bill as they always have,” Menchine said.

The emergency room at County USC in Los Angeles, CA., is one of the busiest in the state. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

Menchine too has felt the same frustration as people on Medi-Cal who can’t find a primary care physician or a specialist.

“I could tell story after story after story of a patient who comes to an ER with an orthopedic injury,” he said.

These patients have broken their arm, have been treated at the emergency department, then ask primary care physicians for referrals to orthopedist, only to “run into the wall,” because there are not enough specialists who take Medi-Cal.

“So they come to the emergency department because they know we’re open,” Menchine said. “It’s frustrating. We can’t get them an orthopedist faster than they can. There’s a frustration at the pace with which these needs need to happen.”

He said the system in place needs improvement.

“It is dizzying to try to get through,” Menchine said. “I’m a physician who knows how to do that stuff. It’s very difficult to navigate the system, especially if they are sick or hurt. It’s really difficult.”

The hospital too has its own resources to direct people with non life threatening illnesses to other programs to receive preventative care. But Menchine acknowledged that the hospital is so big, even patients get discouraged when it comes to using other resources that could help them avoid the emergency department.

The original hospital opened in 1923 and decades later expanded to LAC+USC. It holds several distinctions, including as having the world’s busiest emergency departments.

With the emergency room at County USC being one of the busiest in the state, the hospital has opened The Wellness Center at the old hospital site to promote healthy living. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

It’s one of 13 statewide that is a “level one” trauma center, operates one of three burn centers in Los Angeles County and serves as the host facility for the U.S. Navy’s Trauma Training Center, according to published reports.

In 2014, the hospital opened The Wellness Center inside the original general hospital where organizations such as the American Diabetes Association offer classes in diabetes prevention and management.

Menchine said it’s been a challenge to direct patients to the center, because it’s at another side of the hospital, far from the main entrance of the emergency department, where people continue to come in.

The hospital recently noted that and placed a navigator inside the emergency department, so that patients who leave are given information on how to access primary care and other prevention care at the Wellness Center.

Changing habits, expanding care in the community, and encouraging more prevention will help alleviate the high numbers of visits at the emergency department, Menchine said.

“Over time, the clinics will pop up and the people will get used to going to clinics and we’ll see a dip in emergency medicine,” he said.

Antelope Valley Hospital

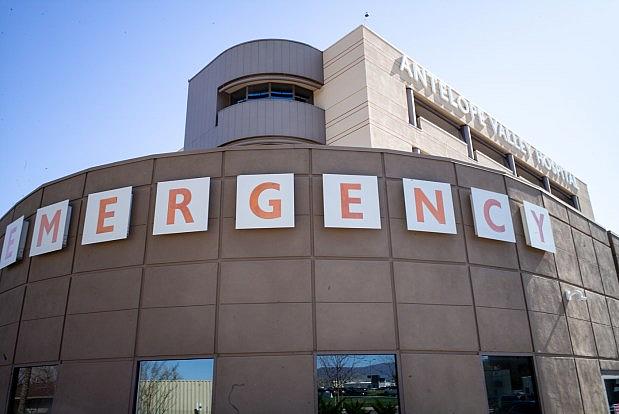

The third busiest emergency department in all of California sits within a 2,200 square mile area, near where Los Angeles County’s border hugs the western tip of the Mojave Desert.

With more than 400 beds, Antelope Valley Hospital is the largest in the region and also one of the most isolated, said President and CEO Michael Wall.

Emergency Services at the Antelope Valley Hospital. (Photo by David Crane, Los Angeles Daily News/SCNG)

“We’re the safety net hospital,” Wall said.

Indeed, a look at the data show that the hospital bears a lot of visits, before and after the Affordable Care Act. It posted the third-highest number of visits in all of California in 2016.

In addition to more visits, the hospital also has endured turmoil in recent years, including a drop in patient confidence and credit rating.

That started to turn around last year.

Wall, considered a 30-year veteran in the healthcare field who oversaw operations at at St. John’s Health Center/John Wayne Cancer Institute in Santa Monica and at Northridge Medical Center, was hired in early 2017.

Late last year, Moody’s Investors Services lifted the hospital’s credit rating from “negative” to “stable.” The rating was raised due to a change in the governance structure, increased stability and stronger cash flow, according to published reports.

Dr. Lawrence Stock, vice chair of the emergency department at Antelope Valley Hospital, said the high number of visits to the emergency department have always been there, both before and after the Affordable Care Act.

In 2010, there were 112,352 visits to the emergency department. By 2016, visits had climbed by 12 percent, to 125,862.

“When the ACA came in full force, we were in the area where it transformed a lot of patients that had no insurance to some kind of coverage, so that was a big factor,” he said. “But that population was misidentified as using the ER in higher numbers. It certainly went up, but it’s not that they used the ER more by percentage.”

He said the Antelope Valley’s population of 500,000 people are growing older and have multiple chronic conditions such as heart disease or lung problems. The hospital also sees a high number of pediatric emergency visits, because there’s no children’s hospital nearby.

“I started in 1996 in the ER and I’ve been there for 22 years. When I started, we saw 40,000 visits,” Stock said. “This year, we’ll hit 140,000. But it is amazing how good our system is. We’re (caring for patients) in a very small space. Patients feel that, but the care is very good.”

With a new board and CEO installed, Wall said more people are coming in for medical services.

“Admissions are up here dramatically primarily because of renewed confidence in the medical services,” Wall said. “I suspect there is not the level of access to primary care, as well.”

The health profile of residents in the area also contributes to the high number of visits and admissions, Wall noted.

Data released by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health last year show that in 2016, Antelope Valley residents placed first in several categories of poor health:

- 14 percent have diabetes

- 14 percent have asthma

- 30 percent are obese

- 11 percent have housing instability

Additionally, 30 percent of residents are on disability, and about 42 percent are unemployed.

Despite its distance from urban areas, Antelope Valley Hospital and those across California will have to evolved to deliver care differently as the health care landscape changes.

“I think all of healthcare delivery will run differently,” he said. “We’ve got a 50 year old plan we’re going to have to replace.

“It’s going to look a lot different,” he added. “There will be more home care, less use of the hospital as we know it today. But it’s going to have the same emergency department.”

[This story was originally published by the Los Angeles Daily News.]