California is facing a toxic, multi-billion dollar problem: how to clean up decades of pollution from the dry cleaning industry.

By conservative estimates, California has 7,500 to 10,000 dry cleaners, at least 75% of which may have caused toxic plumes of perchloroethylene, also known as PCE, to foul the soil and groundwater under cities and towns across the state, according to the California Department of Toxic Substances Control and the state water board.

PCE has been found to cause deadly diseases including cancer, leading state officials to ban its use effective this year. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency also is considering a nationwide ban.

It can cost $1 million to more than $10 million to investigate, remediate and monitor a PCE plume from just one dry cleaner site, according to state water board estimates.

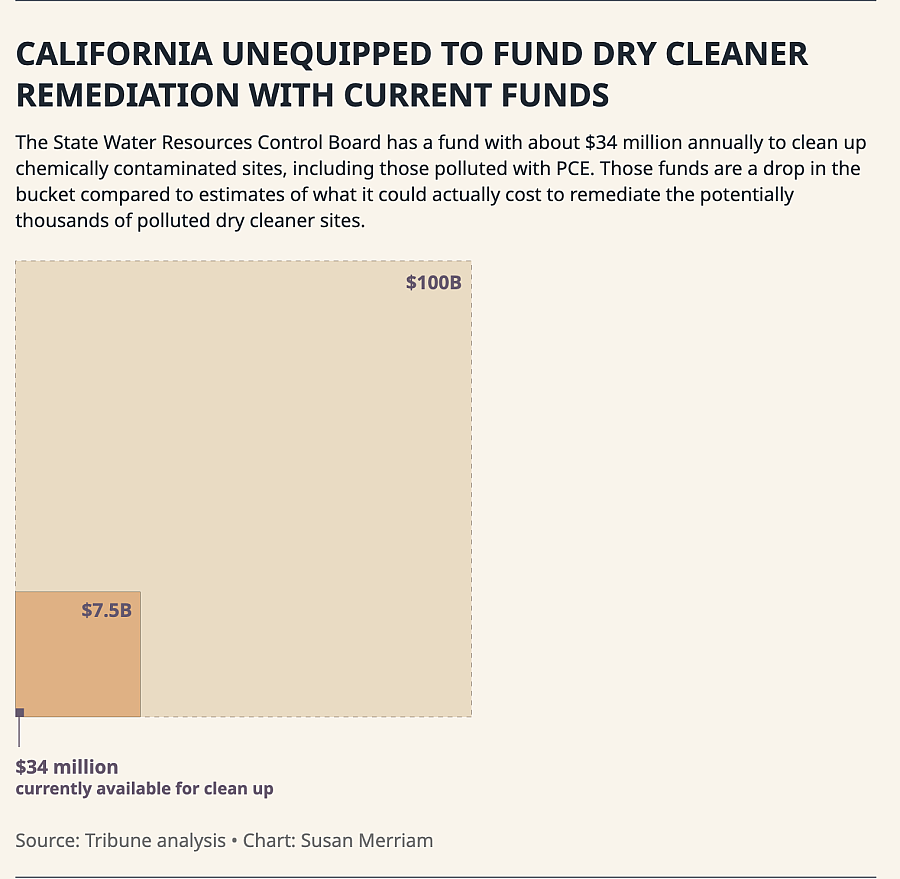

That means it could cost anywhere from $7.5 billion to more than $100 billion to clean up the pollution left by the dry cleaning industry, given the sheer number of potential dry cleaner sites left contaminated.

That’s money that just doesn’t exist right now.

“If we have funding, I think we can make a real difference,” said Cheryl Prowell, the California State Water Quality Control Board’s supervisor of the underground storage tank and cleanup programs section.

Without it, the plumes of pollution will be left to spread and possibly taint critical water sources or vaporize and drift up into homes and businesses.

State officials have known about the massive extent of PCE pollution from dry cleaners since at least the early 1990s. State and environmental consultant reports over the past three decades have shown that entire city water supplies have been polluted with the carcinogenic substance.

But, unlike other states, California has never had a way to fund the cleanup of PCE pollution from dry cleaners.

“We are based on a polluter pays model,” said Prowell. “And so for these dry cleaners, if they don’t have the ability to pay … our ability to work on them is really limited.”

Patricia Hernandez irons a shirt at Prestige Cleaners in Sacramento on July 18, 2023.

Hector Amezcua hamezcua@sacbee.com

STATE HAS ‘NOT ENOUGH’ RESOURCES FOR COSTLY DRY CLEANER POLLUTION REMEDIATION

One way the state has managed to help dry cleaners pay for PCE remediation is through the Site Cleanup Subaccount Program, known as SCAP.

The state water board charges gas stations a fee of 2 cents per gallon for storing petroleum in underground tanks, and of that, a tiny fraction — $0.003 — has gone toward SCAP since 2014.

That revenue stream has produced about $34 million in SCAP funds per year for cleaning up sites contaminated with chemicals such as PCE in cases where the site owner is not otherwise able to pay.

Sometimes other grant funding is available through the state or regional water boards, but SCAP has been the most consistent source of money available for dry cleaners, Prowell said.

Ten years of SCAP funding would add up to about $340 million, a veritable drop in the bucket compared to the need.

And, an even smaller share goes to PCE contamination.

The state water board has more than 5,000 ongoing chemical cleanup cases in SCAP, according to Prowell. Of those, about 700 — or one-seventh of the total — are categorized as dry cleaner cleanups, she added.

“We know it’s not enough, but it’s a step in the right direction,” Prowell said of SCAP funding available for dry cleaner remediation.

The California Department of Toxic Substances Control has also had some grant funding available to dry cleaners, but no dedicated money until recently.

In 2021, Senate Bill 158 allocated $500 million toward cleaning up pollution in disadvantaged communities. Of that, $152 million was put toward investigating dry cleaners in disadvantaged communities for PCE contamination.

But DTSC’s program is solely dedicated to investigating whether a dry cleaner site may have caused a plume of PCE.

It leaves the dry cleaner responsible for finding funds to clean up the pollution, although the agency may offer cleanup grants to businesses if such funding is available.

The $152 million has gone toward hiring staff at the DTSC who this year are investigating 112 dry cleaner sites across the state for potential contamination.

But that is only a first exploratory step and a mere handful of sites out of potentially thousands.

“We’re only scratching the surface,” conceded Rafat Abbasi, DTSC’s chief of the discovery and enforcement program. “Just one industry has about 7,500 sites to investigate. It’ll take forever.”

This dry cleaner in Los Angeles advertises that it cleans client’s clothes “eco-friendly,” meaning it does not use perchloroethylene, or PCE.

Mackenzie Shuman mshuman@thetribunenews.com

TEXAS, FLORIDA AND OTHER STATES HAVE ESTABLISHED DRY CLEANER POLLUTION CLEANUP FUNDS

California isn’t the only state dealing with the vexing problem of PCE pollution.

It could take a cue from others that have established dedicated funds toward cleaning up dry cleaner chemicals.

The State Coalition for Remediation of Drycleaners, created in 1998, was created to help states band together and share resources for how they’ve tackled the PCE pollution issue.

It’s made up of states that have set up remediation programs for dry cleaner pollution, but because California has no such program, it is not in the coalition.

A total of 13 states participate in the coalition: Alabama, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Kansas, Minnesota, Missouri, North Carolina, Oregon, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas and Wisconsin.

In a North Carolina program established in 1997, $10 per gallon of PCE purchased by dry cleaners and 60% of the annual tax collected for the industry goes toward funding site investigations and cleanups.

Aside from a small co-payment, the program covers all of the costs.

Oregon’s program was established because the state legislature recognized that “before the risks were widely known, many dry cleaners contaminated their properties by throwing spent filters and sludge on the ground, or pouring spent solvent and wastewater into a floor drain or leaky sanitary sewer,” according to the program’s website.

“Dumping practices that previously were common are no longer allowed,” the website continues. “However, at some dry cleaner facilities, past disposal and management practices have resulted in contamination of soil and groundwater that requires cleanup.”

Miriam Alcantar examines a shirt after it was ironed at Prestige Cleaners in Sacramento on Tuesday, July 18, 2023.

Hector Amezcua hamezcua@sacbee.com

Dry cleaners in Oregon voiced concerns that expensive PCE cleanups would put them out of business.

So the state responded by establishing the dry cleaner environmental response account and required dry cleaners to pay 1% of their annual revenue plus additional fees if they used PCE to fund the program.

Because the number of dry cleaners in Oregon has diminished over the years, the program has insufficient funds to pay for additional cleanups and will sunset in January.

In Florida, a dry cleaning solvent cleanup program was established by the state’s legislature in 1995.

The program sources revenue from a sales tax on the dry cleaning industry, tax on PCE sold or imported by a business and annual registration fees.

And in Minnesota, a law passed in 1995 established a fund for dry cleaners to apply for reimbursement for their investigation and cleanup work.

Annual registration fees paid by dry cleaning facilities, as well as solvent fees collected by retailers of particular dry cleaning chemicals, are used to finance the fund.

While California works on its own daunting PCE cleanup, at-risk residents are mostly on their own when it comes to protecting their health, with the threat from vaporized chemicals being a vital concern.

So Prowell has a simple message for any Californians who live near a dry cleaning business: Get fresh air. “If you live near a dry cleaner, the more you can do to have fresh air in your home, it will help,” she said.