How ER docs could play a key role in fighting the opioid epidemic

This story was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Is pot the answer to keeping seniors in pain off opioids and other prescription drugs?

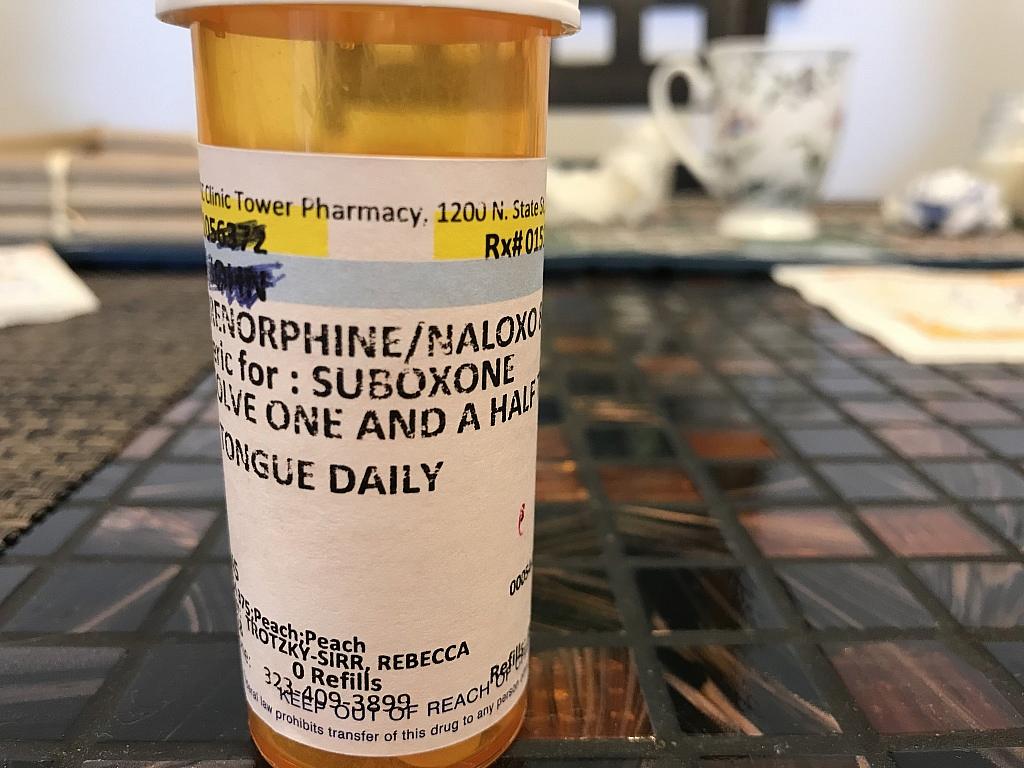

Suboxone, a drug which combines the opioid abuse treatment drug buprenorphine and the overdose reversal drug naloxone, is becoming more common in emergency rooms. Some health care leaders are pushing ER's to take on a bigger role in addressing the opioid epidemic.

Dr. Mary Cheffers monitors patients' vital signs on several computers in the emergency department at L.A. County-USC Medical Center. She explains to a visitor that she's making sure everyone's hearts are operating normally and that no one is experiencing a lack of oxygen.

County USC has one of the largest and busiest ER's in the nation, treating some 500 patients daily. The facility is also the main safety net hospital for L.A. County. It often treats people living on the streets and those without private insurance, as well as inmates from the county’s jail system.

Over her last four years at County USC — at the height of the opioid epidemic — Cheffers has seen many patients experiencing withdrawal from heroin or other opioids.

"They're vomiting. They have goose bumps everywhere. They have terrible diarrhea, terrible cramps and they're just in pain everywhere," she says.

Cheffers has also seen many patients who overdosed on opioids. She says those patients often leave the hospital as soon as they can to find drugs to stave off withdrawal.

Emergency departments are a frequent stop for people hooked on opioids. More than 140,000 people visited an ER for overdoses nationwide between July 2016 and Sept. 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Most ER doctors stabilize patients and release them with little or no attempt to offer long-term treatment.

But momentum is building to get emergency departments to play a bigger role in stemming the epidemic. At County USC, Dr. Rebecca Trotzky is piloting a program that would start treatment for suspected opioid use disorders in the ER.

Trotzky, the facility's medical director of urgent care, says the hospital has been missing a key opportunity to intervene in the cycle of addiction.

"People would come in to the ER because they would have horrible skin infections from injecting unclean needles," she says, "and our system would maybe deal with that with a surgery or antibiotics and then send the person home."

She also notes that traditionally, emergency doctors have refilled existing opioid prescriptions for ER patients without questioning whether the patient might be addicted, or whether giving them more narcotics could be harmful.

"The way we were treating opioid use disorder was by refilling their narcotics," she says. "And that was a completely inefficient, ineffective and dangerous way to deal with a problem."

Under a program she’s piloting, ER patients with signs of opioid addiction are given a medication to stabilize them short-term and then referred to Trotzky or a primary care doctor for follow up. She’s treated about 50 patients over the past year, she says, a number that she hopes will expand significantly as the program ramps up.

BUILDING A BRIDGE TO RECOVERY

The emergency department at LA County-USC Medical Center. Dr. Rebecca Trotsky, who directs urgent care, is helping ER doctors get trained to prescribe buprenorphine, a medication used to treat opioid addiction.

In Trotzky’s ideal emergency department, doctors would likely give a patient in withdrawal, or soon to experience withdrawal, a medication called buprenorphine. It treats pain and withdrawal symptoms, and helps stabilize a patient’s brain that's been thrown off kilter by narcotics. Many health care experts consider buprenorphine to be the gold standard in opioid addiction treatment.

After getting prescribed the drug, a patient would be referred to Trotzky or the patient’s primary care physician for follow-up care.

This model, which some healthcare leaders have dubbed a "warm handoff," is new for most emergency departments.

And there’s another important concept that marks a major change: Treating substance use disorders like any other chronic disease.

What does that mean? Trotzky gives the example of how hospital staff treat an overweight patient with diabetes.

"Never in our right minds would we say we're not going to give the insulin until this patient really shapes up and loses those 200 pounds, because we recognize that that's really hard to do by yourself," she says. "You can say two things at once: I'm going to treat you while I'm hoping that I can encourage you to change your behavior."

U.S. Surgeon General Vice Admiral Jerome Adams echoed that sentiment in an interview on NPR last month.

"I'm focused as surgeon general on making sure everyone sees addiction not as a moral failing but as a chronic disease," Adams said, "and that we have good, evidence-based treatment, including medication-assisted treatment, available for individuals with a warm handoff right from the overdose."

Rhode Island has pioneered the "warm handoff" model. All of the state’s emergency departments and hospitals are now required to be state-certified to treat opioid use disorders. This includes offering peer recovery support; prescribing the overdose reversal drug naloxone to at-risk patients; and offering medication-assisted treatment, including buprenorphine, in the ER or at a doctor’s office or treatment facility.

There's evidence that it works. A recent study by Yale researchers found that opioid-addicted patients were more likely to get treatment and reduce opioid use long-term when started on medication-assisted treatment in the ER.

The California Health Care Foundation has been sponsoring a pilot programsimilar to Trotzky’s in eight hospitals around the state, and the program just got federal funding to expand to more emergency departments.

Kelly Pfeifer, who heads the foundation’s efforts to curb opioid overdoses, says ER doctors are finding that treating opioid-addicted patients with buprenorphine makes their job easier and safer.

"We see a lot of emergency docs who are so jazzed," she says, "because their life is better when they take someone who is screaming in withdrawal, they sit them down in a chair, they put a pill under their tongue, and then they can have an intelligent conversation a half hour later, as opposed to having that person leave, threaten the nurses, sometimes have to be restrained by security."

Watch a video from the California Health Care Foundation about treating opioid addiction in the ER:

Trotzky wants all of County USC’s ER doctors to be able to prescribe buprenorphine.

There are obstacles, however. Perhaps the biggest one is the federal government's requirement that doctors get a special waiver to prescribe the drug. Trotzky says the eight hours of training and additional paperwork required to get the waiver scares many doctors away. (There's a narrow exception for dispensing buprenorphine in the hospital for no more than three days.)

In addition, changing the culture of emergency departments is tough work. The ER is a place that deals with life or death situations. But substance abuse doesn’t have a quick fix.

Ultimately, Trotzky is relying on residents like Dr. Cheffers to champion the program among their peers.

She is, but Cheffers also recognizes that it’s a shift away from the drama that drew her to emergency medicine in the first place.

"The exciting part is ... you give them medicine and they come back to life," she says. "It’s harder to get yourself to do the rest."

By "the rest," Cheffers means mundane and potentially frustrating tasks like calling a social worker and fighting with the pharmacy to get a buprenorphine prescription. Trotzky hopes that when her warm handoff program is standard practice at L.A. County USC, "the rest" won’t be as hard.

Correction: A previous version of this story misspelled Dr. Trotzky's surname.

[This story was originally published by KPCC.]

[Photos by Jill Replogle / KPCC.]