How health inequity maps out across America

The story was originally published in Modern Healthcare with support from our 2022 Data Fellowship.

Getty Images, Kara Hartnett

In Evangeline Parish, a Cajun community in rural south central Louisiana, 1 in 4 people live in poverty. They are oil workers, timbermen and factory hands. Of the 32,000 who call the Acadiana territory home, more than 8,000 have disabilities and 3,000 subsist on less than half of the federal poverty level.

In the Bronx, New York, it can take months to see a medical specialist. Deaths related to pregnancy are eight times more likely there than across the Harlem River in Manhattan. Nurses in New York City's poorest and northernmost borough went on strike in January, when they raised their concerns about unsafe staffing levels and inequality in care delivery.

And in Navajo County, Arizona, 16.4% of residents are uninsured—two times the national rate. Tribal lands are home to nearly half the population. They face a major health crisis: Middle-aged Native Americans have experienced the greatest increases in mortality in the country, largely attributable to a stark rise in deaths related to drug overdose, suicide and alcoholic liver disease.

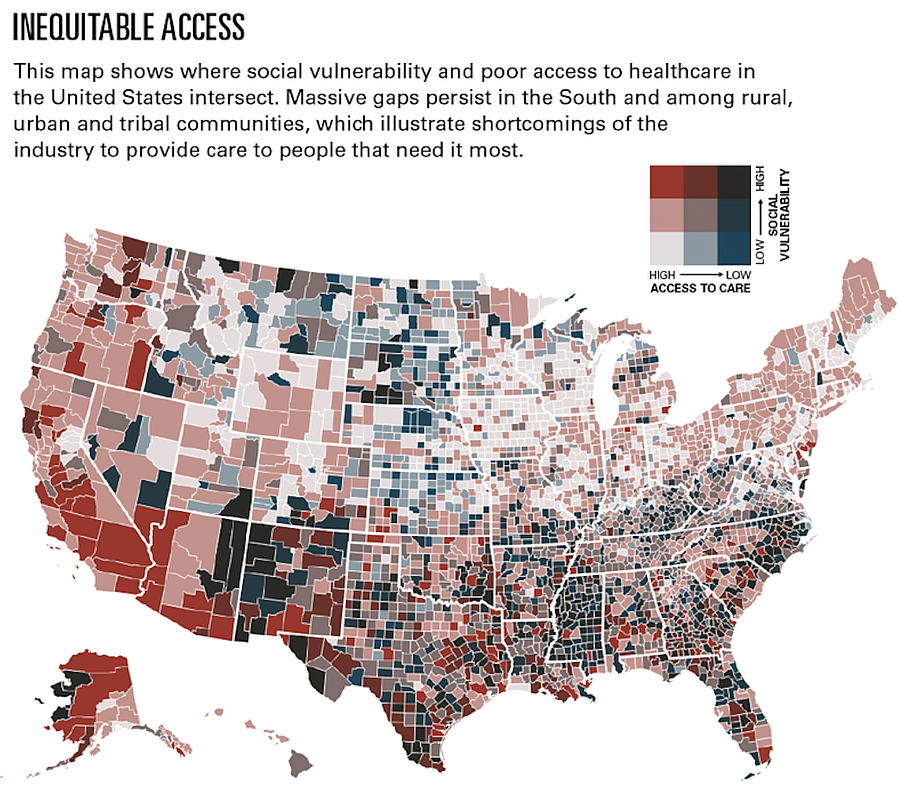

These communities possess unique characteristics that point to the U.S. healthcare system’s shortcomings. With support from the University of Southern California Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism, Modern Healthcare used the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention social vulnerability index and Health Resources and Services Administration access scores to map the regions with the poorest access to healthcare and highest levels of social vulnerability.

Evangeline Parish, Bronx County and Navajo County rank within the 99th percentile for social vulnerability—determined using 14 census metrics related to income and access to food, water and transportation—and are designated medically underserved by the federal government. They have different demographics, built environments, belief systems and opportunities. Within them are health disparities forged by long-standing political and economic forces. Their experiences are common, not exceptional.

The inequities in the nation’s healthcare system stem from its fundamental attributes, beginning with financial incentives to provide “sick care” on a fee-for-service basis and disincentives to offer services that promote health. Access to healthcare also is strongly influenced by patients’ ability to pay. More broadly, a history of oppressive laws and business practices and generations of disinvestment in underserved communities are directly linked to poorer health outcomes and shorter lifespans.

People who are low-income, live in rural areas or are Black, Latino or Native American statistically have higher rates of illnesses such as heart disease and cancer, deaths during pregnancy and behavioral health and substance-use conditions. Drug overdoses and suicides are more common in these areas.

They also have access to fewer resources.

Health industry consolidation has reduced access in poorer and remote areas, which providers eschew because there isn’t enough money to be made. That, in turn, intensifies the stress on an overburdened, underfunded safety net. This misalignment of capital encourages patients toward inefficient sites of care such as emergency departments and costlier interventions that occur only after medical conditions worsen.

Unequal and expensive treatment has sowed distrust between healthcare institutions and the communities they vow to serve, and leads to burnout among healthcare workers. Yet these businesses have little financial reason to change course.

Modern Healthcare analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Health Resources and Services Administration data

Shifting the paradigm

To begin solving inequities, healthcare organizations seeking to promote access, moderate costs and improve health in hard-to-reach places have tapped digital solutions, opened alternative care sites and forged partnerships.

A slow transition to value-based payment is ingraining new financial inducements that tie compensation to better outcomes. Federal and state authorities and private accreditors are devising accountability standards for health equity, redefining governance structures, and advancing data collection, screening and quality-assessment efforts. Major investments have also been made in primary care.

But many of these strategies don’t reach the communities that need them the most. Instead, healthcare organizations devote more resources to the populous, high-income areas where they already operate and target patients who are already engaged with the system.

Healthcare companies have the power to shift the paradigm through direct action and advocacy. But first, the industry must repair broken trust among residents of neglected communities, governments must realign financial incentives and regulations, and both sectors must make investments that lift up socially vulnerable populations over the long term.

“No one entity can do this alone. We need to work together and not point fingers at each other. We need to cross lines and not have silos and redefine what healthcare systems are all about. If they’re really, truly about health, and not generating wealth, we’ll be better off.”

Daniel Wolfson, executive vice president and chief operating officer of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation.

Sick care, not healthcare

There has never been much money in creating health. Paying providers on a per-service basis remains the norm, rather than rewarding them for improving outcomes. Reimbursements vary widely among public and private payers, which gives providers clear financial reasons to favor some patients over others.

In a 2022 study by Yale University, researchers found the bulk of Medicaid patients receive care from a small percentage of doctors. According to the report, 25% of primary care physicians provided 86% of services to Medicaid managed care enrollees, and 25% of specialists provided 75% of the services. A separate study by the Yale School of Medicine in 2019 concluded that people with private insurance are three times more likely to be able to schedule specialty appointments than people with Medicaid.

In sparsely populated and poorer regions, hospital consolidation has hampered access. According to data from the University of North Carolina, 143 rural hospitals closed between 2010 and January 2023. Others cut specialty services such as obstetrics and chemotherapy. Forty-nine percent of the poorest communities had no intensive care beds, compared with 3% of the richest communities, University of Pennsylvania researchers reported in 2020.

“Institutions have moved away from these communities. They’ve moved to the suburbs. They’ve moved to where they get better payment,” Wolfson said.

Nurses from Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx strike amid contentious labor negotiations between the hospital and the nurses union. The three-day labor action ended after hospital leadership agreed to increase wages and hire more nurses. “The fight has just begun,” said Michelle Gonzalez, an ICU nurse (not pictured here).

GETTY IMAGES

‘The cycle continues’

In the Bronx, a predominantly Latino and immigrant community, resources are scarce and challenging to navigate. Approximately 20% of its 1.4 million residents are Medicaid beneficiaries and another 8% are uninsured. Bronx County ranks last in New York state for health outcomes and has the highest rates of asthma and maternal morbidity in the city, disproportionately affecting people of color.

Montefiore Health System is the largest provider, and employer, in the Bronx. The flagship Montefiore Medical Center in the Norwood neighborhood provides the most charity care of any New York City hospital and serves a disproportionate share of uninsured patients, according to the Lown Institute, a nonpartisan think tank.

A three-day labor action in January arose from demands for higher pay, more staffing and an expansion of resources in the Bronx. Nurses said they are overworked and overwhelmed, and feel as though they cannot help patients get healthier. Providers don’t have the capacity to address an array of social challenges such as housing, nutrition and public safety and are constantly triaging, the nurses said.

“There has to be some change. These patients, the mortality rate is high. Their children grow up and they repeat the same cycle. It’s like we’re fighting not just our hospitals, but we’re fighting a system that does not protect these patients,” said Una Davis, a nurse at Montefiore Medical Center. “The cycle continues and I feel as if there is no hope.”

The nurses also noted that the nonprofit health system is investing in tony suburbs north of the city and merging services in the Bronx. Last year, the system consolidated a group of medical practices in low-income areas of the Bronx while expanding less than 20 miles away in White Plains, where the population is whiter and wealthier. New York-Presbyterian and New Hyde Park, New York-based Northwell Health are also rapidly growing in the area north of the Bronx.

“People here can’t go to White Plains because they don’t have the transportation or earnings. But you receive substantially better care there,” Davis said.

Montefiore closed a family practice clinic in the Bronx's Grand Concourse and directed patients to nearby alternate sites because the old one was “suboptimal,” a health system spokesperson said. The company offered transportation assistance to some patients, the spokesperson said.

Beset by the COVID-19 pandemic, the health system had to cut costs and respond to demand in the suburbs, said Joe Solmonese, senior vice president of government relations and strategic communications for Montefiore.

“There is not a direct line between saving money and reducing the quality or the capabilities of care,” he said.

New facilities and expanded service offerings in Westchester County don’t mean Montefiore is disregarding the Bronx, Solmonese said.

“If you didn't know anything about healthcare, I can see where that would be sort of a simplistic view of how you might look at it, but we are a multidimensional system with many hospitals. Each of those hospitals tries to meet the needs of the community,” he said.

Michelle Gonzalez, an intensive care nurse at Montefiore and native Bronxite, said the organization is reinforcing a legacy of segregation in healthcare. “Drive your car to White Plains, where you can get white care,” she quipped.

Route 66 runs west through Holbrook, a predominantly white town in Northern Arizona and the seat of Navajo County. As traffic from the historic highway dwindled, the bustling economy slowed. An hour north into the Colorado Plateau is Navajo Nation and the Hopi Reservation.

KARA HARTNETT

Reliance on the safety net

Data from the Commonwealth Fund, an independent foundation focused on healthcare research, illustrate that the American healthcare system is inefficient and cumbersome, despite rampant spending. The United States has the lowest life expectancy among wealthy industrialized nations and the highest rate of avoidable deaths. Infant and maternal morbidity rates are the highest, and deaths from diabetes, hypertension and certain cancers have been rising since 2015.

The U.S. spends more per capita on healthcare than any other wealthy country, yet many communities lack access to basic services and local governments are overburdened.

Native Americans make up nearly 50% of the population in Navajo County, and midlife mortality among that population is skyrocketing. According to an analysis University of California, Los Angeles, researchers published in January, Native Americans between the ages of 32 and 50 have more than double the death rate of white people in the same age range.

The federal Indian Health Service is notoriously underfunded and understaffed, and private options are sparse.

“We don't have a lot of industry in our area, and we have a high number of our residents that have no health insurance, because they're self-employed, and so they go without healthcare services,” said Janelle Linn, health director of the Navajo County public health agency.

Healthcare organizations in Navajo County struggle to recruit and retain physicians and other health professionals, Linn said. Many come to Indian Health Service facilities to train and receive federal loan forgiveness, but leave after their commitments expire.

“There's not that continuity there,” Linn said. "[Providers] either can't attract them at all, or they agree to come and they can't find housing.” For example, the IHS’ 179,000-square-foot Kayenta Health Center in the county was built in 2016 but has yet to fully open because of a staffing shortage.

Rebecca Cormier and John Reed, co-owners of Reed’s Pharmacy, the local drugstore in Mamou, Louisiana, since 1975, have struggled to keep their family business afloat as pharmacy benefit managers throttle their margins

KARA HARTNETT

Targeting solutions

Healthcare organizations have leaned on several strategies to address access gaps.

Tools meant to connect to patients virtually, like telehealth, took off as the government relaxed regulations in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, and are now commonplace. Yet many in rural and low-income communities lack broadband internet service.

Major healthcare providers and other companies have expanded into alternative care sites such as retail stores and mobile clinics. Dollar General and CVS Health, for example, have the reach to thrive in underserved markets. However, only 10% of patients used retail clinics last year, according to a Deloitte survey. And some consumers have trouble navigating the healthcare system without guidance.

In Mamou, Louisiana, a town of approximately 3,000 people in Evangeline Parish, an independent drugstore open since 1975 is struggling to provide for its longtime customers. In the past year, Reed's Pharmacy has terminated long-standing contracts with insurers and pharmacy benefit managers and has transferred patients’ prescriptions to a Walmart in the next parish.

The drugstore couldn’t get by on what pharmacy benefit managers—often part of the same corporate families as insurers and chain drugstores—charge for the medications and pay for dispensing them, said Rebecca Cormier, pharmacist and co-owner.

“Grocery stores aren't expected to buy bread for $1 and sell it for 50 cents, but that's what they're expecting us to do,” Cormier said.

Reed's is one of two drugstores in Mamou. The other is on the campus of the 60-bed Savoy Medical Center on the edge of town.

Many of Reed's customers have patronized the store their entire lives and lack the health literacy to navigate the healthcare system without help, Cormier said. Only 12% of the town’s population has a college degree and one-quarter has disabilities, according to census data.

“Some of these people can't maneuver a phone tree,” which are used by large companies, including chain drugstores, Cormier said. “We've been serving third and fourth generations of families over here. If you pick up the phone, you’re talking to a pharmacist and a person—you're not pressing ‘one’ to talk to so-and-so.”

For some drugs, Reed's managed to keep the cash price within $20 of what patients were paying with insurance, Cormier said. But for other medicines, including those treating the many locals with asthma and diabetes, the drugstore couldn’t solve the affordability problem.

The recent contract disputes leave those customers with fewer options, especially those without access to transportation, Cormier said.

“They don't have a way to get out of town to get their medicine,” she said. “They're going without their medicine because we can't fill it. No one else in town is going to do it at a loss either, so they will just go without.”

Incentivizing transformation

Emerging market forces are shaping a framework of accountability and financial incentives that aim to close gaps in care. Government agencies and third-party accreditors are imposing standards for data collection, governance and quality research.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services now evaluates how providers incorporate health equity into strategic plans, data collection and analysis, and leadership. The agency also created a “birthing-friendly” designation to encourage hospitals to close maternal morbidity gaps. The Joint Commission, which accredits about 3,800 hospitals, has devised guidelines that include designating officers to lead efforts focused on eliminating disparities and screening patients for social determinants of health.

Health equity advocates also see promise in value-based payment models, but the transition has been slow and the arrangements are not deployed in the locations where they could make the greatest difference. The Medical Group Management Association reports that value-based care accounts for just 5.5% to 14.74% of physician office revenue. CMS is pushing to increase participation, especially for Medicare Advantage members.

Value-based arrangements pay providers a fixed amount of money per person, per month, and allow them to decide how to spend the money. The upfront investment enables providers to build teams based on patient needs and fund community health programs. That includes hiring community health workers, dietitians and social workers or offering screenings and mobile vaccination clinics.

To make it work, providers and payers have to coordinate data and care plans, negotiate risk levels and overhaul revenue models. This would mark a major shift from the fee-for-service model, and it presents significant financial and logistical challenges to providers that benefit from the status quo. Healthcare organizations also have to reach beyond medical care and invest in other interventions to be successful.

“Old habits die hard,” said Dr. Chris Dodd, chief medical officer at Franklin, Tennessee-based home health provider Emcara Health. “Health systems have been traditionally focused on building more hospitals and hiring more specialists and using [primary care providers] to just funnel patients to higher-cost services.”

CMS’ Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation reported in 2021 that pilot programs testing new payment models aren’t being implemented in low-income areas. The agency is working to mitigate this by experimenting with novel payment arrangements under Medicaid and prioritizing interventions in locales identified as underserved by the Center for Health Disparities Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

More flexibility for spending money on social interventions is needed and the federal government should be specific about what kinds of risk-sharing arrangements are proper and what populations should be targeted, said Hugh Lytle, founder and CEO of Equality Health, a population risk management company that enables value-based care arrangements among Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries.

“There's more than enough money in the system to get better results, but the incentives, even under the current value-based care systems, really encourage cherry-picking of the healthy patients and dumping of the less healthy patients,”

Dr. David Ansell, senior vice president for community health equity at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago and co-founder of the Healthcare Anchor Network.