'I was too proud to ask for help,' Vietnamese immigrant says of her struggle with mental illness

This article was produced as a project for the 2016 California Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the Center for Health Journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Family's experience helps Korean Americans change mindset about mental illness

Art class helps erase stigma of mental illness in Arab community

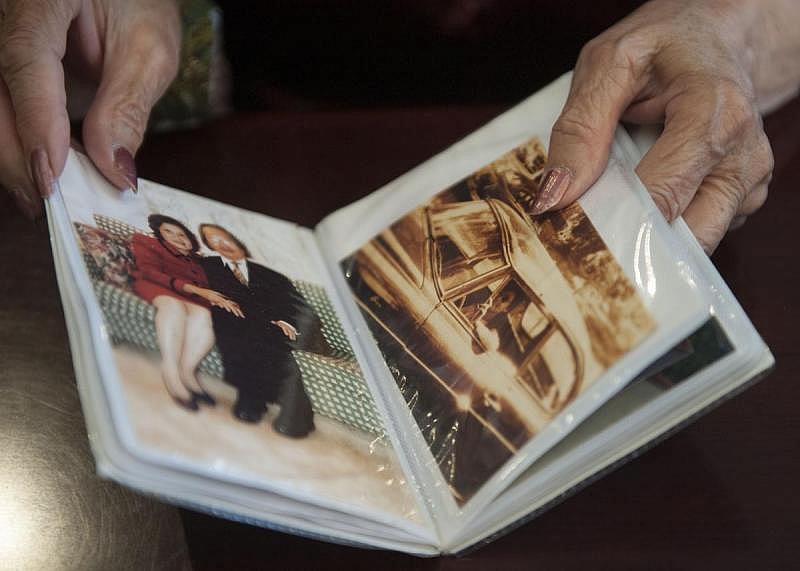

Tri Minh Le, 82, of Westminster, tearfully recalls her late husband. Le is receiving social support and counseling through programs at the Vietnamese Community of Orange County in Westminster.

Four years ago, Lanie Tran was broke and homeless.

The single mother was living in her car with an adult daughter and a son who was going to middle school.

“I felt stuck, like my hands were tied and I couldn’t move,” she said. “I felt ... paralyzed.”

That’s what it took for Tran to eventually seek help from the Vietnamese Community of Orange County – a clinic in Westminster that provides comprehensive health services to the county’s Vietnamese population – to treat her daughter’s, son’s and her own mental health issues, which ranged from depression to schizophrenia.

They also helped her find an apartment and get financial assistance to support her family.

“I was too proud to ask for help,” said Tran, 49, who emigrated from Vietnam in 1998.

Tran was a war orphan who grew up with adoptive parents. In Vietnam, she watched people with mental illnesses stigmatized in school, in public, even within families. Tran did not want that for herself or her children.

“The word we use for mental illness in Vietnamese is ‘crazy,’” she said. “If you’re a Buddhist, you believe you or your family members did something wrong in a previous birth. If you’re Catholic, you believe God is punishing you for something you did that was mean or wrong.”

Tran is just one example of how mental health stigma devastates Vietnamese American families, a majority of whom have been affected by the multiple traumas wrought by war – imprisonment, torture in concentration camps – uprooting their families, fleeing by boat as they fended off pirates and braved turbulent seas, and eventually reestablishing their lives in a different country.

Mold in Kindergarten classroom A-2 at Farrell Elementary.

This expatriate community’s refugee experience and its long process of acculturation play an important role when it comes to mental health issues and the stigma surrounding them, said Kim Xuyen Ngo, a clinician and counselor with the Vietnamese Community of Orange County.

Ngo, her parents and nine siblings were boat people. Her father served in the South Vietnamese Army. His war wounds were not the visible kind.

“He was angry, a lot,” she said. “He drank to cope with his issues. We grew up with verbal abuse. But he didn’t get help. None of us did.”

Her own experience is what inspired Ngo to get into social work, particularly in the mental health arena. She knows she can help her community in a way an outsider couldn’t.

The stigma in the community is so strong that the Vietnamese Community of Orange County’s clinic doesn’t advertise its mental health program by that name. It’s sugar-coated as a “wellness program.”

No big signs mark the clinic’s entrance. Many patients aren’t even seen at the center. Psychiatrists walk with their patients in a neighborhood park, discussing their symptoms and medications. Counselors such as Ngo meet clients at the park for picnic lunches and barbecues.

On a recent afternoon, Ngo met a mother and her son in the park. The mom, who did not want to be identified, grilled meat as Ngo and other counselors from the center set a picnic table with noodles, vegetables and dessert.

After lunch, Ngo sat with the mom in a corner of the picnic shelter, talking about the boy’s progress as he ran about on the playground.

“Look, he’s making friends,” Ngo told the mom, as they wrapped up the session. “That’s great. He’s doing much better.”

Ngo says it’s hard for mothers in the Vietnamese community, whose children are under tremendous pressure to do well in school.

“It’s like, they have to get a 4.0 GPA,” she said. “Of course they don’t want their children to be stigmatized.”

If the clinic publicized its mental health program, not many would walk through its doors, Ngo said.

Scott Vo, a counselor who runs the center’s mental health program for seniors, said he does a number of home visits, particularly for those who hesitate to come to the center because of the stigma.

“Some people just don’t come back because they want nothing to do with a mental health program,” he said. “It’s really unfortunate.”

Melissa Billingsley, a state-licensed risk assessor for Criterion Laboratories, takes a soil sample in a yard located on the 2600 block of East Thompson street. The yard tested high for lead.

Tri Minh Le, 82, of Westminster is a frequent visitor to the center.

She came to the country as a refugee in 1995. She was 62 and her husband was 67. They had lost their home in Vietnam. She lost her job working for an airline, and her husband spent six years in a concentration camp, losing his physician’s license.

“We had no home, no family here for moral support,” she said. “We both suffered from depression.”

But Le was one of those rare individuals in the community who had no hangups about getting help. In fact, she encourages others at the senior center she attends every day.

There’s no shame in getting help when you need it, she tells them.

Thu-Phuong Thi Ha, 66, of Garden Grove says she was judged by others in the senior community when she sought help to treat her depression.

“Some of my friends viewed my illness as fake,” she said. “They said it was something I was making up to get attention. But that wasn’t true. I know what I’ve suffered.”

She’s on track with her counseling and medication, Ha said.

“And it’s helped,” she said. “I don’t care what other people say or think, not anymore.”

[This story was originally published by The Orange County Register.]

[Photos by Ana Venegas/The Orange County Register.]