The Incredible Shrinking Public Health Workforce

Sarah Kliff looks at how public health budget cuts have affected smoking cessation efforts in Worcester, Massachusetts.

Johnson works for the Worcester Department of Public Health, a working-class city one hour west of Boston. Her task is daunting: With a population of 181,000, its smoking rate is 47 percent higher than the rest of the state.

And yet through her efforts, the city’s teen smoking rate dropped year after year. Then so did her budget. In 1998, the department had about $350,000 to spend on tobacco cessation efforts. Today, Johnson has $135,000.

She is not alone. The recession has battered public health; across the country, local and state health departments have shed 52,200 jobs since 2009.

Despite resources from the stimulus and the Affordable Care Act aiming to bolster the public health workforce, it has about 20 percent fewer workers than it did four years ago. Forty-one percent of local health departments expect to make even more cuts this year, according to the National Association of County and City Health Officials. Johnson, who has worked for the public health department for six years, says these cuts could not come at a worse time. After years of steady declines in teenage tobacco use, new data have shown hints of a backslide.

Back in the early 2000s, five full-time staff members worked on smoking cessation in Worcester. Just last year, there was money enough to go around to all 600 tobacco sellers in the area, to make sure they were complying with city regulations and not selling to teens.

This year, Johnson had the budget to visit 300 stores. The rest, she says, “just didn’t get checked.”

“What’s really frustrating is that we do so much work, updating our policies and making them stronger,” Johnson says, “and then can’t really enforce our policies.”

In a way, Worcester is in the middle of a national experiment in public health spending. It will show what happens when public health infrastructure shrinks just as America’s health problems are getting bigger.

“The big picture is that tobacco use remains the leading preventable cause of death in the United States,” said Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “But there was a combination of fiscal crises, and states choose to do other things than tobacco cessation.”

Teachers and firefighters regularly are cast by politicians as the face of local government; their roles are familiar. Public health officials, by contrast, tend to be behind the scenes, the ones running anti-tobacco ads, inspecting restaurants for compliance with health regulations and monitoring populations for disease outbreaks. It’s their job to make public environments healthier.

When public health departments do their best job, the results are elusive. They cannot tally up disease outbreaks prevented the way firefighters can count fires extinguished. And that can make vying for funds from recession-squeezed budgets a tough battle.

“We don’t have blue lights, red lights, flashing around the city,” said Derek Brindisi, Worcester’s public health director. “We’re all behind the scenes, so we can become less of a priority.”

Big gains, eroded

Of all the work American public health departments have done in the past century, smoking cessation is easily their proudest success. A concerted policy effort from local, state and federal agencies dramatically reduced American smoking rates over the course of decades.

Interventions were set in motion in the mid-1960s after the surgeon general first warned of nicotine’s harmful effects. The federal government added warning labels to cigarette packages, followed by a ban on television ads for tobacco in 1969. Arizona, four years later, became the first state to ban smoking in many outdoor places. Nearly 3,500 cities have followed suit.

Public health departments successfully pushed for high cigarette taxes and the average, inflation-adjusted price for a pack of cigarettes increased from $1.80 to $4.15 between 1955 and 2008. They saw results: The American smoking rate fell by half between 1955 and 2008, from 43 percent to 20 percent.

Study after study has found that public health work to combat smoking — providing assistance with quitting, restrictions on public smoking and advertising on the harmful effects of nicotine — is especially effective in reducing youth smoking rates. For public health workers, that’s a key demographic: More than 80 percent of adult smokers begin by age 18.

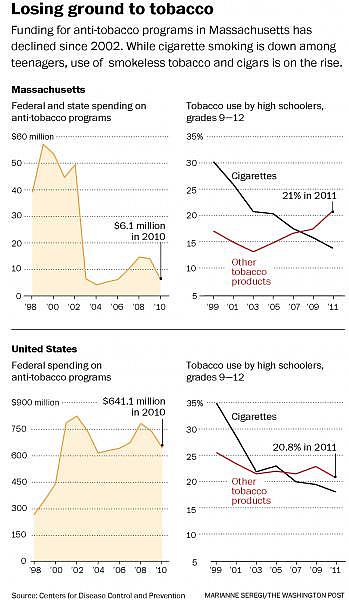

Recent economic downturns have hit smoking cessation budgets, and public health spending in general, hard. Among state health agencies, 89 percent scaled back the services they offer between 2008 and 2010. During that same time, national spending on smoking cessation dropped by 20 percent, mirroring similar cuts made during the recession in the early 2000s.

Funding for tobacco cessation is falling even as the data suggest the problem is as persistent as ever. While cigarette use among teens has declined, on average, by 2 percent a year, use of other tobacco products, such as cigars and smokeless tobacco, has increased.

“Following a sharp decline in use since the late 1990s, the prevalence of current smokeless tobacco use began to rise sharply in 2003 and has continued to rise since,” the Obama administration concluded in the most recent surgeon general’s report, issued in March.

If the declines in youth tobacco use during the 1990s had continued, the Centers for Disease Control estimates, 3 million fewer teens would be smokers.

“The 20th century was the cigarette century,” said Gregory Connolly,who directs Harvard’s Center for Global Tobacco Control. “What’s frightening about the 21st century is it’s the tobacco century. Companies have a total tobacco approach. We may see lower cigarette consumption offset by the use of other forms of tobacco.”

‘Such an uphill battle’

In 1998, Massachusetts had one of the country’s biggest tobacco cessation budgets, spending $39 million in state and federal dollars — second only to California. Massachusetts has some of the most stringent restrictions on smoking in public places.

Cuts made during the past two recessions, in the early and then the late 2000s, have changed that. By 2010, combined state and federal spending on smoking cessation in Massachusetts had fallen to $6.8 million, about 17 percent of the 1998 budget. Massachusetts now ranks 35th in its spending. Overall public health spending has dropped, since 2006, by 14 percent.

In Worcester, that means no more nicotine patch handouts; Worcester’s last was in 2008. There are fewer checks to make sure tobacco retailers are complying with regulations, and less resources to push back if they aren’t.

Lately, Johnson has seen a wave of non-cigarette products coming to market. She collects the ones she finds in a red plastic bag in her office. Some are in brightly colored tins that look like they might contain mints. Others are small cigars, called cigarillos, that have fruity flavors and sell for 59 cents. These products tend to be taxed at 5 to 10 percent of the rate for cigarettes.

“There’s a lot of people trying to do good policy work, but it seems like every time we get a handle on the products out there, it changes,” Johnson said. “We ban blunt wraps, and describe them as ‘brown paper’ in the city ordinance, and all of a sudden there are green blunt wraps.”

As in the rest of the nation, use of these products among the young has been on the rise in Massachusetts, from 13 percent of teens in 2002 to 17.6 percent in 2009.

In Worcester, 21 percent of teens use some kind of tobacco product, cigarette or otherwise. With the adult and youth smoking rates nearly identical, the number is unlikely to bend downward.

“It’s definitely alarming, because we’re putting all this energy into protecting youth from cigarettes and they’re just using different products,” Johnson said. “We’re trying to bend the adult smoking rate down from 22 percent but youth are at 21 percent. This is just such an uphill battle.”

Trying new approaches

With Massachusetts’ spending on tobacco cessation down, it’s looked to other ways to tackle the issue. “Our policies continue to create an environment where the norm is not smoking,” Massachusetts Public Health Department director John Auerbach said. “The combination of good state policy and federal money, with the health-care reform impact, it’s made it easier for us to continue this downward trend.”

Federal funds have patched some budget holes: The state has kept its tobacco quit line open with hundreds of thousands of dollars from the health reform law’s Prevention and Public Health Fund, a $15 billion federal commitment to preventive health care.

The quit line is among a handful in the country that is “proactive,” meaning that quit-line workers will, after being flagged by a doctor, reach out to a smoker.

Local hospitals have begun to ban smoking on their campuses. In 2010, Massachusetts became the first state to require Medicaid to cover a wide range of smoking cessation products. It has shown immediate returns: Each dollar invested in that program has returned $3.12 in savings from reductions in cardiovascular-related hospital admissions, according an analysis by George Washington University.

The state does still, however, run into obstacles. Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick (D) proposed a $1.7 million increase in tobacco cessation spending this year. It would have included $500,000 for local teen smoking prevention.

The Massachusetts’ legislature rejected the extra funding. A dollar tax increase on tobacco products also was left on the cutting-room floor.

Johnson has joined forces with 18 smaller cities near Worcester. Collectively, their budget is the same as Worcester’s in 1998. They meet regularly, develop policies together and pool resources for store compliance checks.

In May, Johnson got some good news: Her budget would grow in 2013, enough to once again cover an annual check of every tobacco seller.

It feels like a small victory for a department that touches every life, but often completely out of view.

“I have this idea of coming up with a video of what cities used to be like in the 1900s just to show what a big impact public health departments have had,” Brindisi said. “Sometimes, I feel like we should just get a helicopter so people know we’re here.”

This story was originally published on The Washington Post.