Its patients are ‘literally a captive market.’ Is this California health care giant failing them?

The story was originally published by the San Francisco Chronicle with support from the our 2022 National Fellowship.

Sabel Gonzalez kisses a photo of her son, Sergio Guzman Gonzalez Jr., while at his grave at Holy Trinity Catholic Church cemetery in Greenfield (Monterey County) in April 2022. Sergio died after developing COVID-19 during a major outbreak in Monterey County Jail in 2021. Isabel and other members of her family say they believe the jail mishandled the outbreak and are suing the county.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

A health care company specializing in jails has rapidly expanded in California in recent years, securing dozens of lucrative public contracts while facing allegations in lawsuits and government investigations that it provides substandard care to its uniquely vulnerable clients.

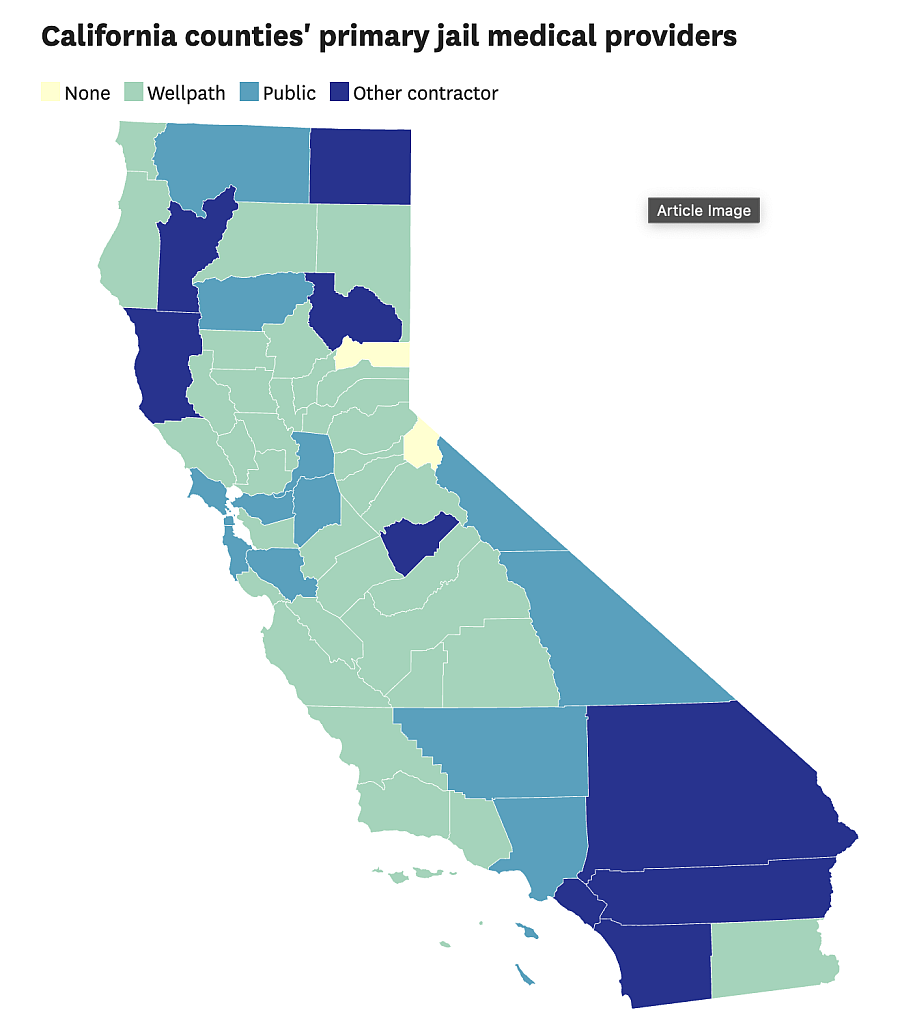

Wellpath provides health care in 34 of California’s 56 county jail systems, including in four of the Bay Area’s nine counties. The number vastly exceeds any other correctional provider in the state. In multiple instances, the for-profit company has secured multimillion-dollar county contracts without facing a single competitive bid, raising questions about whether local taxpayers are getting a good deal.

Leaders of Wellpath, which is owned by the global investment firm H.I.G. Capital, say the company’s size is a strength. Jail health care is difficult to provide under any circumstances, and officials say the outfit’s cost-efficiency and industry expertise make it superior to most other providers.

“Our partners choose Wellpath because we provide quality, compassionate care in line with the most rigorous industry standards,” Wellpath spokesperson Chris Hartline told The Chronicle in a written statement.

Natividad Medical Center is near the Monterey County Jail, where Sergio Guzman Gonzalez Jr. died during a major COVID-19 outbreak in 2021. Sergio’s family says it believes the jail mishandled the outbreak and did not provide the care he needed when a hospital was only a two-minute drive away.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

But as Wellpath’s footprint has grown — mirroring broader trends toward consolidation and private equity investment in the health care industry — so have the concerns of prisoner rights advocates. The advocates point to more than 1,000 lawsuits in U.S. federal courts, filed by prisoners, their families and civil rights groups, naming the company as a defendant, and three recent investigations involving Wellpath’s quality of care by the U.S. Department of Justice.

They also cite four FBI investigations — three into the company’s health care delivery and one into bribery allegations involving Gerard “Jerry” Boyle, the founder of one of the two companies that merged to become Wellpath and who pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit mail fraud. In February 2022, a federal judge sentenced Boyle, who is now retired, to three years in prison and ordered him to pay a $35,000 fine. A Wellpath spokesperson called the charges against Boyle “serious” in a statement in 2019 and said the company had “accepted his resignation.”

In San Luis Obispo County, the Justice Department concluded that Wellpath did not provide a “significant” improvement over a jail’s former government-run system after the company’s takeover in February 2019 — a system whose deficient care had prompted the investigation.

Sergio Gonzalez watches television at his home in Mexicali, Baja California, near a picture of his son, Sergio.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

In a 2020 probe into the Massachusetts Department of Corrections, the DOJ found Wellpath’s mental health care was so abysmal that it may have violated the U.S. Constitution’s protections against “cruel and unusual punishment,” with “vague” policies that increased the risk of self-harm and suicide among mentally ill prisoners. A follow-up report this year revealed that Wellpath had low staffing levels and high rates of unlicensed mental health providers. The Massachusetts Department of Corrections disputed the DOJ’s findings and denied all constitutional violations.

The third Justice Department investigation focused on Correct Care Solutions, which became Wellpath in 2018 after merging with California Forensic Medical Group. Investigators found that the company failed to develop a quality-control plan and overbilled the state for its medical services in a Florida prison. The Federal Bureau of Prisons, which had awarded the contract to CCS, agreed with the DOJ’s recommendations on how it could better monitor the company’s performance.

Hartline said the issues identified in the San Luis Obispo County investigation have since been resolved, and that the company did “not agree” with the Justice Department’s findings in the Massachusetts and Florida probes.

“Like all health care organizations, Wellpath occasionally experiences unfortunate outcomes,” he said. “These isolated events occur despite all the policies, procedures, systems and training we do to prevent them.”

To understand Wellpath’s growth and the resistance it has faced, The Chronicle reviewed thousands of pages of documents including lawsuits, health care contracts, regulatory reports and research articles. The Chronicle also interviewed correctional health care experts, civil rights attorneys, private equity scholars, prisoner rights advocates and former Wellpath employees.

Corene Kendrick, who has followed the rise of Wellpath as deputy director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project, said the company’s growth is concerning because it has few incentives to provide top-quality health care, due to the lack of competition and regulation it faces. The ACLU seeks to improve conditions in jails and prisons and reduce incarceration overall.

“Whatever the company can save becomes their pure profit,” said Kendrick, who directs civil litigation and policy advocacy for incarcerated people. “It’s this really dysfunctional funding structure, and it’s not like people can (seek other options). … They’re literally a captive market.”

The Sonoma County Main Adult Detention Facility in Santa Rosa.

Ramin Rahimian/Special to The Chronicle

Federal investigation finds possible ‘constitutional violations’

In fall 2018, the Justice Department opened an investigation into the San Luis Obispo County Jail’s health care system. Twelve people had died over five years, a per-person rate twice the state average for jails. The toll included Andrew Holland, a 36-year-old man suffering from schizophrenia who died of fatal blood clots after being strapped to a chair, naked and masked, for 46 hours, according to local news reports.

Around the same time, Sheriff Ian Parkinson announced the county would enlist Wellpath to help address the jail’s issues. Heralded as a “new chapter” for the jail, Wellpath pledged via a $6.8 million annual contract to improve the county jail’s medical services while cutting costs; the county estimated it would need to spend $9 million to provide in-house health care.

Wellpath took over in February 2019; the DOJ investigators stuck around for six months after that. And in August 2021, the department released its findings. “Medical care under Wellpath has not significantly improved,” said the report, which concluded the company’s health care may have failed the minimum standard set by the U.S. Constitution to protect prisoners from “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Under Wellpath, the jail staffed a single part-time psychiatrist to care for more than 100 people diagnosed with serious mental illnesses, the report said. One HIV-positive patient had to wait months to start getting crucial antiretroviral therapy, according to the report, while another was given ineffective pills that can create drug-resistant strains of the disease.

Another patient was not physically examined for more than a week after complaining of stomach pain and blood in his stool, according to the report. When a Wellpath nurse finally sent him to the emergency room, hospital staff found he had lost almost half his blood volume. The patient nearly died, staying at the hospital for five days in critical condition.

When prisoners complained about the jail’s quality of care, a Wellpath administrator mocked them. “STOP WHINING AND FIND SOMETHING TO DO,” read the text of a meme the administrator inserted in a PowerPoint presentation presented to jail leadership.

Kip Hallman, chairman of Wellpath’s board of directors and former company president, told the San Luis Obispo Tribune at the time that the investigation occurred during a “transition” period, when the company’s services were “not yet fully stable,” adding that “virtually all issues identified in the DOJ report … have been resolved.” A Justice Department spokesperson, Thom Mrozek, said the investigation “remains open” but otherwise declined to comment.

A titan of the jail health care industry

Wellpath is now the nation’s largest private jail health care business. Born of a 2018 merger between two large conglomerates, the company serves about 300,000 people across more than 530 U.S. jails, prisons and behavioral health facilities. The jails in California counties with Wellpath contracts house roughly 17,000 to 21,000 people a day and provide an estimated 36,000-plus medical appointments or visits a month.

It is a challenge to which Wellpath is uniquely suited, according to the company.

“Because we provide health care for nearly 300,000 patients nationwide, we have significant buying and negotiating power, which allows us to secure the best possible rates with on-site and off-site providers,” Wellpath said in a winning 2020 contract proposal submitted to Klamath County, Ore. Hartline added that the company is “squarely focused on providing a complex set of services to a unique patient population in a way that is difficult for others to match.”

But Marc Stern, a correctional health care expert, said the company’s focus on profit may push it to spend less on actual care — making it more likely to understaff jails, hire underqualified medical professionals and buy lower-quality equipment.

Say “we have $100, that’s all county commissioners have given us,” Stern said. “If you hire your own employees to do it you have $100. If you hire Wellpath they need to make a profit, (so) the first $10 is gonna go to Wellpath stakeholders. You’re actually going to be spending $90” on health care.

Kendrick, the ACLU deputy director, said counties often offer Wellpath a per diem rate per prisoner per day — an arrangement Wellpath acknowledges in its promotional materials — which could spur the company to provide fewer, cheaper services to keep profit margins high.

Hartline said the criticism reflected “a fundamental misunderstanding of Wellpath’s business,” adding that the company’s contracts are “structured to avoid financial benefit” from increases in patient population. He also referenced the company’s 2021 Corporate Responsibility report, which states that Wellpath “annually donates income from operations exceeding 5% of revenue” to health-equity nonprofits.

The company’s profit margins are high, according to available estimates. Wellpath is a private company, so its finances are not public record, but Hallman told the Atlantic in 2019 its margins were in the ballpark of 10%, and corporate data broker Pitchbook estimated its 2022 revenue at about $2 billion. If profits held steady, that would have been close to $200 million in profit last year.

With growth has come scrutiny. A 2020 Reuters investigation of large jails found that patients at institutions using Wellpath and other private providers died at higher rates than at jails with public health care. The investigation found that from 2016 to 2018, for every 10,000 inmates in Wellpath’s care, 16 died; in publicly run jails, that rate was 13 per 10,000.

In response to Reuters, Hallman said that companies often hire contractors like Wellpath when they’re struggling, so comparing death rates at such facilities to other jails would be like comparing “apples to oranges.” Hartline added that the company stands by Hallman’s statement.

Advocates for prisoners said they believed that the care provided by Wellpath was not uniformly worse than other public or private providers. The issue, they say, is that Wellpath has the cash flow to be providing much better care than it is.

“They have an incentive to cut costs, which means cut quality,” said Bianca Tylek, executive director of the nonprofit organization Worth Rises, which seeks to lower incarceration and what it calls the commercialization of the criminal justice system.

Natividad Medical Center is near Monterey County Jail, where Sergio Gonzalez Jr. died after developing COVID-19 during a major outbreak in 2021.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

The consequences of consolidation

Wellpath’s parent company, H.I.G. Capital, has deep roots in the prison and jail business. Headquartered in a glassy skyscraper in downtown Miami, the $57 billion firm’s hundreds of investments have included TKC Holdings, a prison food vendor, and Securus Technologies, a prison phone company.

H.I.G. entered jail health care in 2012 by buying the California Forensic Medical Group, California’s jail health care giant headquartered in Monterey. Over the next six years, H.I.G. bought at least four other correctional health care companies and merged them, christening the new parent company Wellpath.

The conglomerate is by far the dominant player in the market, its estimated $2 billion revenue dwarfing competitors such as Corizon Health and Armor Correctional Health Services.

The business maneuvers that created Wellpath are called “roll-up” mergers in private equity parlance, said Eileen Appelbaum, a co-director at the Center for Economic and Policy Research and a private equity expert. In this strategy, a firm purchases groups of companies in the same space — often direct competitors — as H.I.G. did with Wellpath.

These conglomerates are often capable of offering “efficiencies,” or cost savings, that allow them to out-compete smaller companies, Appelbaum said. But in the long run, their market control can drive costs up and quality down for consumers. In the case of Wellpath, that would mean higher prices for county governments and reduced care for jail patients.

“Once they establish a dominant position … they can set the price,” she said.

Hartline said the company “fundamentally” disagreed with criticisms that the company faced no significant competition, noting that the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission approved the merger that created Wellpath. “In virtually every business opportunity we pursue, we face competition from multiple other bidders,” he added.

Cassandra Ordoñez, right, and boyfriend Natividad Chavez, make signs in August 2022 to protest the treatment of Monterey County Jail inmates.

Nic Coury/Special to The Chronicle

Sean Foote, a professor at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business who teaches classes on private equity and venture capital, noted that roll-up mergers like the one H.I.G. orchestrated can, if managed well, improve companies’ functioning and profits, citing the airline industry as an example.

But if regulators don’t step in when private equity firms try to go “one roll-up too far,” he said, advocates may be rightly concerned about the company’s “undue power” in contract negotiations or price-setting.

Wellpath’s market dominance was cited during a 2021 meeting of the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors, when Supervisor David Rabbitt asked Sheriff-Coroner Eddie Engram why the only bid the county had received for its $63 million jail health care contract was from Wellpath.

“Is this a common occurrence for this type of service?” Rabbitt asked.

Engram told Rabbitt that Wellpath had cornered California’s private jail health care market. “It seems to me that medical correctional companies sort of have a territory, so to speak,” he said, noting that Wellpath’s territory included most of California.

When Wellpath was formed, it absorbed the California Forensic Medical Group — and instantly took over that company’s contracts. The company has won contracts in several other counties since then, and in at least one county, Del Norte, it did so with no significant competition. In San Luis Obispo County, two of the three companies originally competing for the jail’s health care contract — California Forensic Medical Group and Correct Care Solutions — later merged to become Wellpath.

Wellpath hasn’t lost a single contract to provide health care in a California county jail since its 2018 founding, even when serious allegations have surfaced. In Monterey County, supervisors voted unanimously to extend the company’s contract through 2025 last November, one month after they announced that a Wellpath medical director was under investigation for allegedly giving deputies medications meant for sick prisoners. Hartline, the Wellpath spokesperson, declined to comment, citing the fact that the investigation was ongoing.

This year, four people have died in the Monterey County Jail. That’s roughly 1 for every 200 people typically imprisoned there.

Sergio Guzman Gonzalez Jr. died after developing COVID-19 in 2021 in a major outbreak in the Monterey County Jail.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

Overwhelmed nurses and delays in care

As Wellpath has grown, attorneys, independent court monitors and health care unions have found that the company routinely fails to adequately staff California county jails with qualified nurses and doctors, meaning that sick patients often must wait weeks — or, in emergency situations, crucial minutes or hours — to be treated.

In Yuba County, attorneys appointed by the local Superior Court to monitor the jail’s compliance with a decades-old settlement agreement alleging poor conditions found that Wellpath consistently failed to staff enough nurses and therapists to abide by the settlement’s terms in both 2020 and 2021. Hartline declined to comment on the settlement agreement, citing Wellpath’s policy not to comment on pending litigation.

At the Sonoma County Jail, the National Union of Healthcare Workers, a group that represents many Wellpath nurses in California, sent a report to the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors finding that from December 2021 through March 2022, the jail staffed less than two-thirds of the nurse-hours that were required by their contract. The staffing levels in the jail were so low last March, the union’s report found, that for every 500 prisoners in the Sonoma system, just one registered nurse was on duty at any given time. California does not have minimum medical staffing requirements for jails.

Dana Martin is a registered nurse with Wellpath and representative for the National Union of Healthcare Workers.

Ramin Rahimian/Special to The Chronicle

Dana Martin, a registered nurse who works for Wellpath at the Sonoma County Jail and is a NUHW representative, said that Wellpath’s takeover from the California Forensic Medical Group hasn’t improved working conditions or patient care.

“There hasn’t been a benefit in pay, there hasn’t been a benefit in wages, there hasn’t been a benefit in communication, supplies, or tools, you know, training, none of that,” Martin said.

Martin said Wellpath is contractually obligated to fill certain positions with registered nurses. But when it has trouble doing so, it staffs those positions with licensed vocational nurses, who typically do not complete as much training and are not allowed to make as many decisions regarding patient care. Martin’s union sent a letter to Sonoma County last April highlighting its concerns that licensed vocational nurses were being assigned to registered nurse-level work. Martin is worried about the company’s ability to staff its jails nationwide due to the strains the pandemic has put on health care workers.

“I love what I do, love who I do it with, (but) just don’t like who I do it for,” she said.

Hartline said that the COVID-19 pandemic had “strained” the company’s efforts to attract new staff, issues that have been exacerbated by “the unique challenges presented by some sites we serve, including rigorous security clearance processes or rural locations.” Health care institutions of all kinds are experiencing shortages of trained nurses, a problem the pandemic exacerbated.

The Chronicle reached out to dozens of former Wellpath employees on LinkedIn, five of whom responded. Two of the five nurses, and Martin of NUHW, said they had resorted to purchasing their own medical supplies, such as stethoscopes, thermometers and N95 masks. Three of the five said they were often responsible for a number of patients that felt unsafe or impossible to manage.

“I don’t feel safe with 600 patients. That’s not an OK ratio. Nowhere in the world is that an OK ratio,” said Emily Jenkins, a former Wellpath nurse at the Yolo County Jail and Juvenile Detention Facility in Woodland from January to March 2020. Jenkins said she quit two months into her tenure after she experienced panic attacks.

Wellpath Board Chair and former president Kip Hallman told the Atlantic in 2019 that the company has never “intentionally” understaffed or cut costs to improve profit margins. Hartline, who agreed with Hallman’s earlier statement, also told The Chronicle the company spent over $75 million on protective equipment and supplies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Chronicle reviewed dozens of lawsuits filed against Wellpath in California. In one suit filed in August 2020, a woman alleged that the company’s medical staff hadn’t sent her to the hospital while she was having a stroke inside Lake County’s jail in Lakeport the previous summer, keeping her in a sobering cell for more than 20 hours as her condition deteriorated.

Like Martin, the woman said the company had improperly replaced registered nurses with licensed vocational nurses. She also alleged that Wellpath delayed her hospital visit because it charged the county a flat rate “per prisoner, per day,” and knew that external referrals increased expenses. Court records indicate the case was dismissed after the parties went through mediation; attorneys for California Forensic Medical Group, the company that Wellpath absorbed, denied the woman’s allegations in court documents. Hartline declined to comment on the lawsuit, citing Wellpath’s policy not to comment on pending litigation.

In 2019, Rafael Lara entered the Monterey County Jail with a documented history of schizophrenia and alcohol abuse, according to a lawsuit filed by his family. But Wellpath staff didn’t provide Lara with regular doses of antipsychotic medication or resources for alcohol withdrawal, the suit stated. For more than three months, Lara’s mental state deteriorated — until that December, when he became fixated on water and drank so much that his body’s sodium level plummeted until he died.

Lara’s family’s lawsuit says Wellpath supervisors failed to “train, supervise and monitor” the jail’s mental health care providers, contributing to his death. Monterey County officials settled the case for $2.5 million last year, a sum that the county split with Wellpath. Wellpath denied the allegations in Lara’s lawsuit. Hartline declined to comment on the lawsuit, citing Wellpath’s policy not to comment on pending litigation.

Cassandra Ordoñez holds her daughter Sahrayiah, 4, at her home in Greenfield.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

Cassandra Ordoñez was nearly eight months into a high-risk pregnancy when she entered the Monterey County jail in November 2019. She told The Chronicle she filed multiple sick call slips requesting prenatal care, but said that medical staff saw her only once — three weeks after she arrived.

Fresh flowers at the grave of Sergio Guzman Gonzalez Jr. at Holy Trinity Catholic Church cemetery in Greenfield (Monterey County)

Brontë Wittpenn / The Chronicle

“I understand the negligence. I’ve seen it, I’ve been there,” Ordoñez said. “I understand we went in there for a reason and we’re there to pay for our mistakes, but never with our life.” Ordoñez was released seven days before her baby, a healthy girl, was born. Hartline declined to comment on Ordoñez’s allegations.

In 2021, Ordoñez’s cousin, Sergio Guzman Gonzalez, died in the jail. Gonzalez’s mother and daughters sued Wellpath and Monterey County, saying that Wellpath’s medical team was poorly trained and had failed to properly test and treat sick prisoners as a COVID-19 outbreak swept through the county jail in Salinas, infecting nearly 200 people.

Gonzalez tested positive for the coronavirus in early September 2021. Two weeks later, he woke up on Sept. 24, complaining of chest pains and breathing difficulties, according to the coroner’s report.

“He was actually crawling,” said fellow prisoner Arcadio Perez, one of 10 men imprisoned with Gonzalez on the morning of Sept. 24 who spoke to The Chronicle.

His fellow prisoners began yelling and pounding on the doors to notify staff of a “man-down emergency,” actions that should have brought medical staff members to his side within seconds, former jail guard Jose Mendoza told The Chronicle, based on his knowledge of the jail’s layout and its emergency medical procedures. Instead, it took them approximately 15 minutes to arrive, according to Gonzalez’s fellow prisoners. The Chronicle reviewed a diagram of the jail’s layout, which shows the jail’s dormitory section is adjacent to the infirmary.

Jonathan Ordoñez, 13, embraces his sister Sahrayiah, 4, at the grave of cousin Sergio Guzman Gonzalez Jr. at a cemetery near Holy Trinity Church in Greenfield (Monterey County).

Brontë Wittpenn / The Chronicle

Gonzalez died at a nearby hospital that morning, according to his coroner’s report.

Fellow prisoner Carlos Marinelli said he heard Gonzalez saying that morning that, “ ‘It hurts, bro, it hurts.’ Next thing you know, he’s gone.”

Gonzalez’s case is ongoing. Hartline declined to comment on the lawsuit, citing Wellpath’s policy not to comment on pending litigation. Wellpath has not yet appeared in the lawsuit, nor has it responded to the allegations in court filings to date

Gonzalez’s mother, Isabel Gonzalez, said she still wonders whether her son could have survived if jail staff had gotten to him sooner.

“The hospital is right behind” the jail, Gonzalez told The Chronicle. “I go, come on, they couldn’t make it? …The hospital is right there. I don’t think they even paid attention to him, that’s the way I see it.”

Weak regulations, little enforcement

Sergio and Isabel Gonzalez’s son died after developing COVID-19 while incarcerated at Monterey County Jail in 2021.

Brontë Wittpenn/The Chronicle

Because Wellpath faces little competition, it’s unlikely to face meaningful financial consequences for its alleged misconduct, Appelbaum, the private equity expert, told The Chronicle.

“If there’s a competitor, and the quality of care goes down and you’re not happy, you say, ‘OK, I’m not renewing this contract. I’m contracting with this other company,’ ” she said. “But if there’s no other company, then you’re stuck.”

Hartline denied that the correctional health care industry faces little competition, adding that the company has competitors in a majority of its bidding processes.

California’s regulatory agency for jails lacks both specific health care guidelines and the ability to enforce them, ACLU Policy Counsel Jacob Reisberg said.

“I’d use the word ‘weak,’ ” said Reisberg, who advocates on behalf of prisoners in Southern California. “The bar is unbelievably low in terms of what the (Board of State and Community Corrections) says are the minimum standards to follow. … On top of that, there’s the lack of enforcement ability even when a given jail falls under those very low bars.”

California’s jails are required to meet the Title 15 and Title 24 minimum standards for California jails, developed by the BSCC. But these standards, and the BSCC itself, are mostly toothless, according to the California Legislative Analyst’s Office.

In a blistering report published in February 2021, the office found that the BSCC’s board members, nearly half of whom helped manage jails, had “an incentive to avoid” setting standards that would be expensive or difficult to meet.

Because current standards are so vague, jails that meet them aren’t necessarily “humane” or “safe,” according to the report. For instance, instead of specifying how jails should contain infectious diseases, Title 15 simply requires that jail administrators develop “a written plan” to deal with them. The BSCC also has no way to penalize jails that violate its standards.

The Legislative Analyst’s Office report concluded that it was impossible to tell whether the BSCC “should even continue to exist.” Caitlin O’Neil, primary author on the report, told The Chronicle that the fundamental issues “still remain” as of this spring.

Lawsuits filed by prisoners and their advocates probably won’t force major changes, as large companies such as Wellpath can weather them, said Lori Rifkin, a civil rights attorney who represents families in wrongful death lawsuits. While the sum of Wellpath’s civil settlements is unknown, she said the amount is probably dwarfed by the company’s profits.

“To me,” Rifkin said, “what that says is that these deaths — and any damages they have to pay from them — appear to be the cost of doing business.”