Jamaica's 'barrel children' often come up empty with a parent abroad

Melissa Noel reported this story with the support of the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism, a program of the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism. Additional support was provided by the International Center For Journalists ‘Bringing Home The World International Reporting Fellowship’ and The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

This is the first installment of the Love In A Barrel series.

Dr. Claudette Crawford-Brown interacts with Shaniqua Long during an art therapy session at Shortwood Practising Infant, Primary and Junior High School in Kingston, Jamaica. Long's mother migrated to the United States. Sabriya Simon

KINGSTON, Jamaica — School soccer games and award ceremonies always trigger painful reminders for 15-year-old Lejeane Reid. They remind him that his father is not there. When Lejeane was 8, his father moved to Canada for a job opportunity, leaving him behind in Jamaica.

“I remember that he migrated when my baby brother was just born, and it affected me in a way because the only way I can contact him or see him is over the phone," said the teenager as he nervously tugged at the bottom of his powder-blue shirt.

As Lejeane waits for friends after school, he shares his love of Social Studies and English. “I do good in school and I want to be a lawyer but I don’t know if my dad knows that,” he said. “He don’t really keep up with me anymore.”

Children like Lejeane whose parents move abroad, most likely for work, are often referred to as "barrel children," after the circular brown fiber or blue plastic shipping containers used to send material support to those that are back home. However, what can't be shipped in these containers and is therefore missing from the lives of these children, is emotional nurturance.

These children are often left in the care of relatives or friends for extended periods of time. When a family member (in this case a parent) moves abroad, it can take two to 10 years or more to satisfy the legal, financial, and immigration requirements of countries like the United States to bring other family members over. Some "barrel children" never see their parents again.

Although Lejeane does not remember much about the day his father left home eight years ago, he says he will never forget how he "just felt left out.”

Lejeane says his father used to send barrels packed with clothes, food and other necessities every few months. But he can’t remember the last time he received anything at all, not even a phone call. “He can call and ask how are you doing, but he don’t call and those things. If I don’t call, he don’t call,” Lejeane said. “Sometimes when my mom calls, or I call he doesn’t want to talk to us.

Although he has his mother, two siblings, and now a stepfather he says he often feels alone and is sometimes angry because his father no longer makes an effort to maintain a relationship with him.

His hopes of a father-son relationship or for a reunion with his dad have turned to resentment. “It’s like, he don’t remember us," Lejeane said. "I don’t really have that strong feeling to say that he is the one that would be there for me. Not now, not ever.”

In more than 30 interviews over six months with children, teachers, mental health professionals, parents and others in Jamaica and New York City — home to the largest Caribbean diaspora, and one of the largest Jamaican ones, in the United States — NBCBLK explored the complexities of parental migration from the Caribbean and the affect this separation can have on the psychological and emotional well-being of children throughout their lives.

This phenomenon can be found in almost any country with substantial migration. In Kingston, Jamaica's capital, 74 percent of households in some inner-city communities have at least one child left behind by one or both parents. Regionally, the Caribbean has lost more than five million people to migration in the last 50 years.

This long history of migration has made it a normal, yet integral aspect of life in the Caribbean. Jamaicans, like many across the region, often leave home out of economic necessity. They want to earn more, have access to steady employment and send remittances (cash items or noncash items) home.

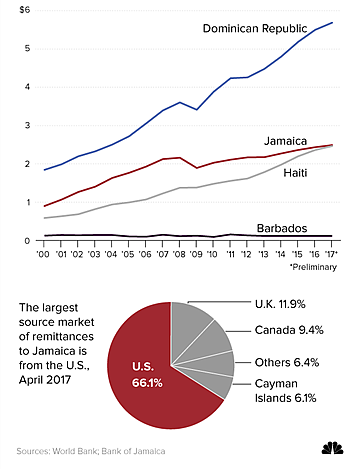

Remittances are important contributions to the economy as a supplemental source of income for many households. The Bank of Jamaica reported that from January to April of 2017, $752 million (USD) was received in remittances.

Supporting families back home in the Caribbean -- Migrant remittance inflows for several Caribbean nations, in billions.

Nachia Haughton was 3 when her mother left Jamaica in 1991. “From as long as I can remember, no one in my household has ever worked in Jamaica. The entire household is supported from people living abroad,” said Haughton, who grew up with her grandparents in Trelawny, a community about two and half hours outside of Kingston.

“If she was living here with a minimum-wage job, she couldn't afford to do that,” said Haughton, now 26. She gets choked up when she talks about it. “It’s like you have to live with the fact that she’s always away, just to get everything you need for your necessity.”

Necessities like food, clothing and household goods often arrive in barrels. For decades, those who’ve migrated to countries like the U.S have sent home barrels. This shipment usually coincides with celebratory times such as Christmas, Easter and birthdays. They’re also sent during the summer or before a school term begins.

Barrels also represent an attempt at maintaining an emotional connection. “It's a metaphor for the actual love that they want to give to their families. I think it all represents the person who is sending the barrel, because they're not able to physically put themselves in a barrel, but that's in essence, that's what they're doing,” said Jamaican visual artist Kelley-Ann Lindo. Her most recent artwork focuses on how people communicate through distance.

Clinical social worker, Dr. Claudette Crawford-Brown agrees but said sending material goods in barrels is not enough. “It leaves devastating consequences on children,” she said.

Dr. Crawford-Brown, a lecturer at the University of The West Indies, Mona Campus has been studying this issue for over 30 years and said this has to do with the disposition and development of the child left behind. “It’s not every stage you can leave a child, especially in early childhood when their personality and a parent-child bond is in development."

In the 1990’s she coined the term ‘barrel child’ to destigmatize the derogatory way these children were referred to and shed light on the damaging effects children can experience when there is no emotional support. “You have deep psychological reactions and they revolve around feelings of worthlessness, sadness, feeling that they're not worth something … that pain can last a lifetime,” she explained.

According to Dr. Crawford-Brown, feelings of abandonment and depression can lead to behavior problems such as running away from home, turning to drugs and alcohol or sometimes engaging in violence. These feelings can also lead to acting out in school and poor academic performance.

“What happens is that when the parents were there you realize that the child has been stable. So the work was more up to standard, the child has been more focused, explained Sophia Williams, a teacher at Shortwood Practising Infant, Primary and Junior High School in Kingston. Williams has had students affected by migration in all of her classes over the last ten years. “After a while you realize that this child is no longer where he or she used to be. When you take time out as a teacher to find out why is it that you're not performing at the level that you normally perform, you find out that mommy or daddy has migrated and it is affecting them.”

The emotional and psychological impact this experience has on some children has even turned fatal. “We’ve had cases of barrel children who have killed themselves, not very often but I remember them because I’ve consulted on it. It’s not something you can forget,” Crawford-Brown said as she recalled the story of an 11-year-old girl who lost a pair of eyeglasses and so feared being beaten by her uncle that she hanged herself from a mango tree.

Dr. Crawford-Brown stresses that while there have been some positive changes regarding awareness of these longstanding issues, there’s not yet enough understanding on the part of parents about the impact their migration will have on the well-being of their children.

Clinical Psychologist Dr. Audrey Pottinger agrees and adds that the issue is not just parent and child. It’s also a societal issue as well.

A 2005 comparative study Dr. Pottinger published in the Journal of Children’s Issues Coalition found that the children whose parents died, tended to fare better than those who were estranged from parents due to migration or parental separation (i.e. divorce).

“I was actually surprised when I found that because I thought death is so permanent that, that should have had more of the impact, but when I looked into it and tried to explain it, I realized death is acknowledged, death is supported,” she said.

“They will say, your parents have gone away, good man, you’re going get things coming back for you… And so you find that the children grieve inside because if they are seen to be grieving, they will be asked but what you crying for, your mother has gone away and is going get things and send them for you,” said Dr. Pottinger. “With parental migration, it's actually lauded, it’s praised.”

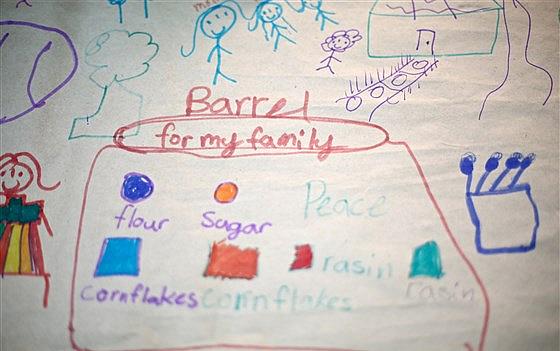

A child whose mother migrated to New York City draws the barrels she receives and some of the things that come inside. Sabriya Simon

These experts say that children who adjust well to a parent’s migration often do so because adequate plans are put in place before a parent’s departure and there is both regular as well as meaningful communication.

Communication has made a difference for Nachia Haughton. Although she and her mother have never spent more than two weeks in the same household over the last twenty-three years, they are best friends. “If my mom had left and didn't support me or talk to me often, or disband me, or hardly speak to me, and get a new life over there, I don't even know where I would be now. I can’t even think about it because I would be lost”.

Now in her final year as an accounting major at The University of The West Indies, Mona Campus, Haughton is grateful because it's the salary her mother earns as a nurse in Canada that’s putting her through school and taking care of her grandparents. Her message to parents who migrate is to make communication with their children a priority. “Find a way to contact your child…Speak to them as often as possible, get involved in their life, know their decisions, know when they're sad, know when they're unhappy. Just communicate,” she said.

In some cases, even with regular support and communication, a parent’s physical absence can affect the relationship.

“I would say that the bond that my mother would hope that we have, we don't necessarily have and I think that had to do with the fact that I had to sort of separate myself to kind of keep myself from hurting,” said Kelley-Ann Lindo.

The 25-year-old’s parents left Jamaica for the United States sixteen years ago. “So now it's almost like she would say I don't care or like I'm really cold towards her but it's that's not the case.”

Lindo said her recent exhibit ‘Send Love Inna Barrel’ isn’t just art, but also a reflection of some experiences in her childhood. “I do love you, I do care for you, but that closeness that she would want it's just not there and you know I think she blames herself sometimes. But what are you going to do, sometimes if you're not physically there for someone it can put a strain on the relationship,” she said.

[This story was originally published by NBC News.]