Lack of trust puts Black moms and their babies at risk

The story was originally published in The Charlotte Post with the support from the 2022 Data Fellowship.

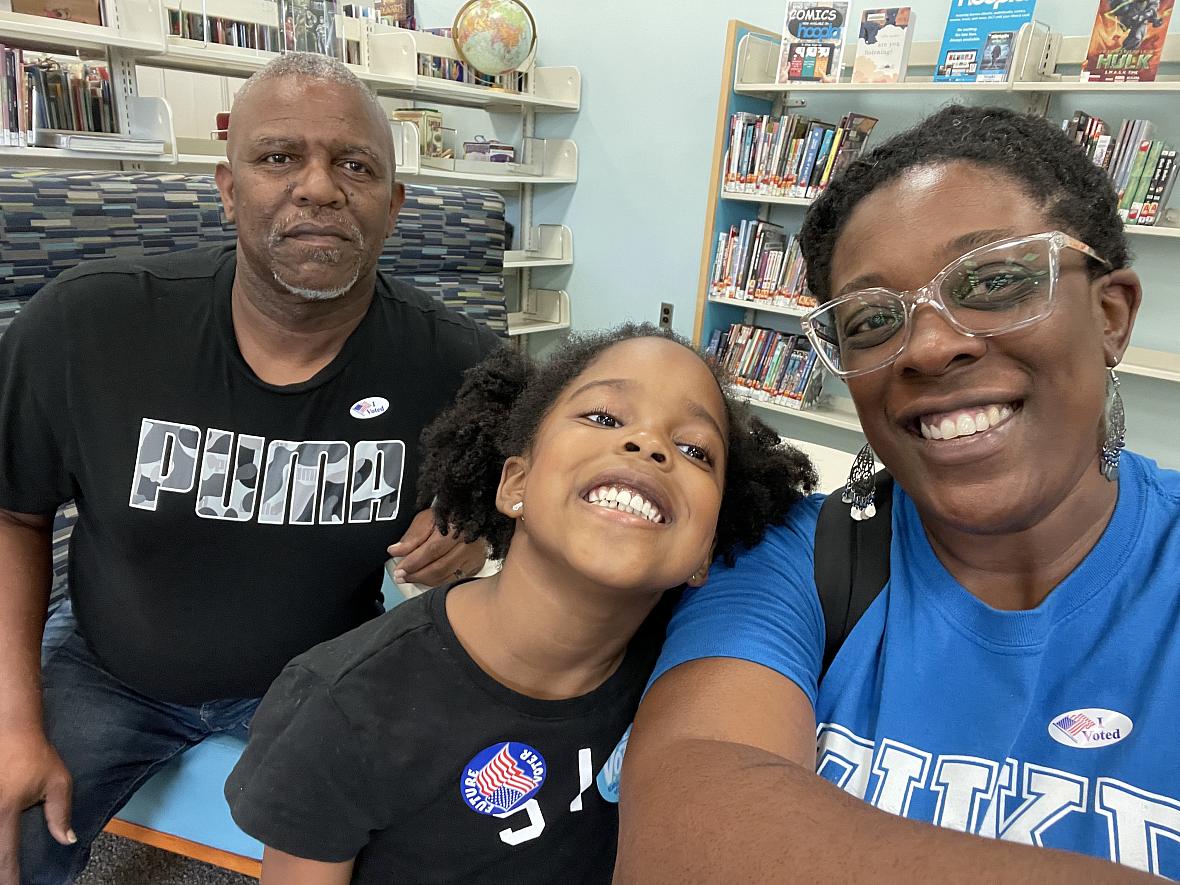

Shaimaica Ferguson, who lives in Conover, N.C., suffered a heart attack while pregnant with her third child. Her husband Thomas and daughter Amani are pictured in this family photo.

COURTESY SHAIMAICA FERGUSON

Shaimaica Ferguson didn’t think anything of the shoulder pain that radiated during her pregnancy.

“I would tell the doctor like I’m super tired,” said Ferguson, who lives in Conover, N.C. “They [were] like ‘well, it might be because you’re a little older. You’re carrying her a little differently than the first two [children].’ I just kind of chalked it up as I am older and closer to 40.”

Ferguson was 36 at the time.

With her older children, Ferguson didn’t have major pregnancy complications. No high blood pressure. No diabetes. Nothing. She was perfectly healthy.

In 2017, it was completely different. Ferguson had a heart attack at 34 weeks of gestation. She was rushed to the hospital with a clogged artery and had stents put in immediately. The stents were not holding well, so doctors decided to transfer her to Novant Health Forsyth Center in Winston-Salem, about an hour away to receive advanced care. Once Ferguson was at the hospital, doctors put stents in again.

However, they noticed she started having trouble breathing, which meant her baby was losing oxygen fast. They decided to do an emergency C-section.

After surgery, Ferguson was placed on a ventilator and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or an ECMO machine, which works as a form of life support for people with a life-threatening condition that affects their heart or lungs, according to John Hopkins Medicine.

ECMO keeps blood moving through the body and balances oxygen and carbon dioxide, but there is a 50% chance the patient will live.

“We do this in only very certain instances where we feel it is meaningful because patients who need ECMO are certainly almost always at the brink of death,” said Tom Theruvath, a cardiac surgeon at Novant Health. When Ferguson woke up, she thought she had lost her baby. Instead, she had given birth to a healthy baby girl named Amani, weighing 4 pounds 13 ounces, on July 28, 2017. Ferguson was hospitalized for two weeks, and the baby spent that time in neonatal intensive care.

If it wasn’t for the pregnancy, Ferguson wouldn’t have known about her heart condition — spontaneous left anterior descending coronary artery dissection — in which a small tear forms in a blood vessel in the heart. The condition is rare in pregnant women.

A lack of trust in the healthcare system is common among Black mothers and experts believe it might be a large reason why Black infant mortality rates are so high. North Carolina has one of the highest rates in the nation and is triple that for white babies and double the Hispanic rate.

Those rates have not changed much over the past decade, according to state data.

Rates and causes

The top four causes of death in 2021 for Black infants in North Carolina were: unknown causes of death, prematurity and low birth weight, conditions originating in the perinatal period (ex. birth traumas and injuries, disorders of newborn gestation and fetal growth, etc), and birth defects.

“You have to have good food. You have to have safe neighborhoods,” said doula Kelle Pressley-Perkins of Charlotte, who provides physical and emotional support to families during pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum. “You have to have outlets to combat our everyday stresses, may it be a barrier of transportation, getting to care, may it be a barrier of proper nutrition and knowing how to get it.”

In 2021, the infant mortality rate for the Charlotte-Mecklenburg area was 4.6 per 1,000 births. In 2020, Mecklenburg County had the highest total number of infant deaths among North Carolina’s 100 counties at 75 deaths for a rate of 5.1 per 1,000 births.

With two prominent hospital systems in the Charlotte region, one would think infant mortality disparities would be narrower, but that’s not the case.

“At Atrium Health, we are committed to improving overall infant mortality while also focusing on the significantly higher risk of infant mortality for Black infants,” said Ngina Connors, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Atrium Health in Charlotte. “We have multidisciplinary teams that review our quality measures for maternal and infant health.”

Infant mortality rates are calculated by the number of deaths in the first year of life divided by the number of live births, and multiplied by 1,000, according to the nonprofit March of Dimes.

From 2017-2021, there were more than 4,000 infant deaths in North Carolina. Mecklenburg and Wake counties are the largest in terms of population and had the highest number of infant deaths during the four-year period. Their mortality rates, however, were significantly lower than Guilford and Forsyth counties, which are third and fourth in population.

From 2017-2021, Forsyth had an infant mortality rate of 8.7 and Guilford’s rate was 8.6.

Mecklenburg’s Black-white gap was wider than Guilford’s, exceeding the state and United States’ rates in 2020.

Preterm birth is when a baby is born before 37 weeks of pregnancy, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Wake County, which includes Raleigh, had a better preterm rate than Mecklenburg. According to the 2022 March of Dimes Report Card, Wake scored a B-plus, an improvement from 2021. Mecklenburg, on the other hand, scored a C grade, an improvement from the previous year.

Charlotte’s preterm rates worsened, earning a D-plus.

Cumberland County, in the eastern part of the state, received a D grade but is improving.

Rural counties typically have fewer total death numbers, but higher infant mortality rates per 1,000 births. One of the reasons is the relative lack of access to health care.

“We don’t have enough doctors, believe it or not, who work in those areas,” said U.S. Rep. Alma Adams, a Democrat from Charlotte. “We don’t have [healthcare] facilities [there]. People have to go further away to get care and so forth, so there are a number of issues I think that are barriers that create problems for women.”

For instance, in 2020, Chatham County had a total of eight infant deaths but at a rate of 12.4.

“They are struggling to continue to [serve] pregnant women, which is also not good for infant mortality,” said state Sen. Natalie Murdock, a Democrat who represents Chatham and Durham counties. “They are working really hard to make sure that they keep their maternal facility that they have in partnership with UNC Health.”

The preterm birth rate in Durham County has worsened, according to the 2022 March of Dimes Report Card. The county scored a C-minus. In 2020, the charity Equity Before Birth was started in Durham with a mission to save more Black and brown people by increasing access to services and support. Their vision is for all babies to have the opportunity to thrive.

“We're very committed to working alongside the community within the community,” keeping our ears close to the ground, to meet the needs of families here locally [In Durham] and to serve them in the best way,” said Joy Spencer, executive director for Equity Before Birth. “[We] build relationships and gain trust and great people around the support they need to be will feel competent and be well prepared for their pregnancy, labor, delivery and postpartum.”

The organization aims to eliminate financial barriers for people of color during their pregnancy.

“We cover the cost of doula services,” Spencer said. “We cover the cost of midwifery services, we cover the cost of therapy. We also give direct cash assistance so that people can have assistance with transportation getting through their doctor appointments, whether it's prenatal appointments, postpartum checkups, or even visits to the NICU. Since a lot of families aren’t able to stay the night and have to go back and forth to visit their infant when their infant has a NICU stay.” Since 2020, Equity Before Birth has served 121 families and has given $54,000 directly to families in the Triangle area for essential baby items such as diapers, formula, car seats, wipes, and more.

The organization has received more than $267,000 in donations, with 100% of the money going toward connecting families with support and services. Another caveat to babies dying in the state and across the United States is the lack of trust from doctors.

Lack of trust

While the lack of access to pregnancy and postpartum care for Black mothers remains a top concern, the lack of trust in the health system among Black women has contributed to the crisis in maternal health. “It has been consistent that [doctors] don’t think that we understand our bodies and they don't think that we should have more of the insight of our bodies than they have,” said Pressley-Perkins.

Natalie C. Carter, 43, who lives in Charlotte, developed gestational diabetes during all three pregnancies.

In 2016, when she was pregnant with her second son Ethan, she developed gestational diabetes and very high blood pressure known as preeclampsia. During her first pregnancy, she also had developed preeclampsia, therefore the doctors decided to deliver this baby early to reduce the risk of complications.

Prior to labor and delivery, doctors gave Carter a steroid shot to help develop the baby’s lungs. The steroid required two doses. Carter had the option to stay at the hospital after the first dose or go home. She opted to go home, but doctors did not warn her of the risk of increased blood sugar.

“They didn’t say to me if you go home, your baby could die. If you go home, this is unsafe,” said Carter, who serves on the board for the local nonprofit KinderMourn, which supports bereaved parents, children and teens. “If I'd stayed in the hospital, they would have seen my blood sugar going up and somebody would have done something. But I didn't know any better and so I came back and took the [second] steroid shot. I thought everything was fine.”

Carter’s son, Ethan, was stillborn on Oct. 10, 2016, at Novant Health Presbyterian Hospital.

“In my chart, they have all different reasons why he died but I was left unmonitored and unchecked,” said Carter, a former KinderMourn client. In 2020, when Carter had her youngest son, Amir, she switched hospitals and delivered at Novant Health Matthews Medical Center instead. After informing the doctors of her previous medical history and doctor mistreatment, she received better care.

“I had over 40 nurses taking care of me during COVID. I was monitored twice a day,” she said. “The treatment was so different. Most of my nurses were white, but I felt well treated.”

Shakira Balerna, 36, said there were times during her pregnancy in 2021 that she felt she was not treated fairly by the health care system.

“My last doctor's appointment, I went to go see my [OB-GYN] and she's really busy on Friday, and she was two hours late,” said Balerna, who lives in Charlotte.

Her doctor delayed switching her medications for blood thinners. At 36 weeks of pregnancy, Balerna went to Novant Health Presbyterian Hospital after she noticed her baby wasn’t moving as much in the womb. “I feel like when you go to the hospital, and you say my baby's not moving, that it will be a sense of urgency, but the nurses are like, ‘OK, fill out this paperwork,’” Balerna said.

Balerna’s daughter Halle died on June 30, 2021. After Halle’s death, doctors discovered Balerna had a concealed placental abruption, in which blood is trapped behind the placenta and there is little to no vaginal bleeding during labor. If her doctor would have switched her blood thinner medication in time, it could have prevented her from having this condition and her baby most likely would have survived.

Balerna said she also experienced mistreatment at her follow-up appointment.

“There were a few instances that were very insensitive,” she said. “The person checking me out, she was like, ‘congratulations! How's your baby?” Balerna, who is pregnant, is receiving care from a different doctor. After informing her doctor of her previous pregnancy, she will be monitored twice a week.

Doulas encourage maternal mothers to be their own advocate at the doctor’s office.

“We try to help the moms find her voice,” said Pressley-Perkins, who is the founder of The Pink Grasshopper Doula and Training Services in Charlotte. “Our essential job is to make sure she's informed, she's empowered, and she's as comfortable as possible.”

Ferguson is in better health now and her daughter, Amani, who is now five years old, is doing great.

“She's fun, she’s loving, she's caring,” Ferguson said. “She's everything wrapped up and she's a total blessing to our house.”