At least 54 died since 2018 waiting for state hospital opening, senator calls for more tracking

This project was produced as a project for the USC Center for Health Journalism's 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories by David Barer include:

Mental competency consequences: the hidden, unreliable data Texas tracks… or doesn’t

Wrong races, hidden names among data challenges our team faced with jail mental health project

Austin court’s redirection of those committing low-level crimes could be saving taxpayer money

Mental Competency Consequences: The Hidden and Unreliable Data Texas Tracks — Or Doesn't

State of Texas: Leaders consider ‘consequences’ of not tracking state hospital waitlist data

‘Horrifying’ wait times for state hospital beds, official says

A state hospital death in restraints and seclusion: What happened to Justin Reeder?

Jail waitlist for mental health help hits new record. This plan proposes a statewide fix.

State mental hospital backlog grows, new record exceeds 2,500 waiting in jail

Despite waitlist record, leaders keep pushing ‘Eliminate the Wait’ plan for state hospitals

AUSTIN (KXAN) – Walter Macias still struggles to retell the unfortunate arc of his brother Fernando’s life. What began as a normal childhood developed into mental illness in early adulthood, which led to a downward spiral of schizophrenia and other disorders that culminated, in 2018, with being found unresponsive at the age of 61 in a San Antonio jail cell.

As Walter recounts it, multiple facets of the criminal justice system failed his brother. He was involved in a daylong standoff with county and state police at the family home he shared with his mother. The situation ended in a shootout with police, and when the smoke cleared, their mother Amelia was dead. That disaster likely could have been averted, Walter said, but what came next, when Fernando languished in jail, was an injustice he believes should never have happened.

Fernando was charged with multiple counts of attempted capital murder of a police officer. He was found incompetent to stand trial, meaning his mental illness was so severe he couldn’t understand or participate in his own defense. His case was paused until he could be sent to a state hospital for competency restoration, which is treatment to stabilize a person mentally to allow them to move forward with their case.

But there was a problem. The state’s mental hospitals were full. Fernando was put on a waitlist for a state hospital bed, but he died before getting there.

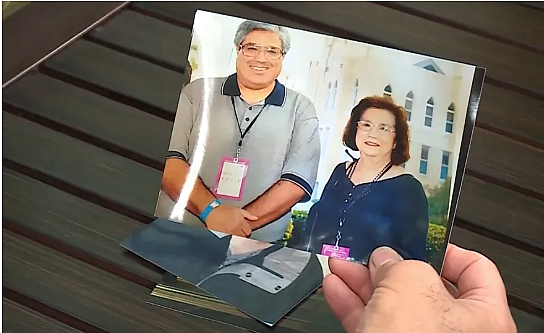

Fernando Macias and his mother, Amelia Macias. Amelia was shot and killed in the family’s home during a 2018 standoff between Fernando and law enforcement.

(Courtesy Walter Macias)

Back in mid-2018, there were roughly 400 people ahead of Fernando on the state’s maximum security state hospital waitlist, waiting an average of nearly 200 days, according to state data.

Fast forward six years, and a legislatively-prompted report by the Texas State Auditor’s Office shows Fernando’s situation was far from an isolated incident.

Dozens of other mentally incompetent men and women have died awaiting placement in a state hospital, and thousands more have been left for months in jail waiting for a state hospital bed. Despite years of work, billions spent on state hospital renovations, and the creation of alternative programs for competency restoration, Texas still has a significant state hospital backlog.

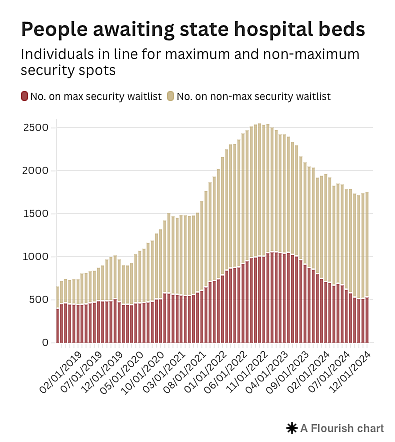

The total waitlist reached a record level in October 2022, with over 2,550 people waiting.

HHSC tracks the number of people waiting for a state hospital bed. There are two waitlists — one for maximum security beds and another for non-maximum security. There are fewer maximum-security beds available, making wait times for those beds longer, according to HHSC data from the Joint Committee on Access and Forensic Services.

HHSC (KXAN Interactive/David Barer)

Dying in line

KXAN has investigated the state hospital waitlist and backlog for years. In 2021, KXAN’s investigation Mental Competency Consequences found the Texas Health and Human Services Commission did not track when people were dying while waiting for a state hospital bed, and no other state agency maintained a list of individuals who died in jail.

HHSC acknowledged in January that it still does not track that information, but it does remove people from the waitlist when given a notification by “by a court or another stakeholder that the individual was deceased.”

Auditors discovered 54 incompetent people – like Fernando – died while they were on the state hospital waitlist between September 2018 and December 2023.

Of those deaths, 30 occurred in jails and were reported to the Texas Commission on Jail Standards – 20 of that number were from natural causes, eight were from unknown or undetermined causes, one was an accident, and another was a homicide, the audit found.

An additional 24 others “weren’t necessarily in custody at the time of death” because some were eligible for bond and could have been back in the community.

Fernando’s death was categorized as natural, according to his custodial death report. Walter questions how well that description portrays his brother’s death.

While Fernando had serious medical issues including renal failure, he was rejecting his medication, dialysis treatment and had lost over 100 pounds while in custody, according to Walter and court records.

“A guy that’s mentally ill, is he … really in the right frame of mind to care for his own health and to refuse something like that?” Walter said. “He might have wanted to live.”

It is not just people in Fernando’s situation who are affected by the waitlist. It impacts both sides of the criminal justice equation, with victims of crimes left waiting for justice as well.

Victims in limbo

“The old adage is, ‘justice delayed is justice denied,’ both for the individual who is accused, but also for any victims,” State Sen. Sarah Eckhardt, D-Austin, told KXAN in an interview at her Capitol office. “This wait time is not only an injustice to the individual who has a serious psychiatric diagnosis and is in need of medical care, but it’s also a disservice … in the criminal justice context.”

State Sen. Sarah Eckhardt, D-Austin, has advanced legislation in multiple sessions with the goal of shoring up the state’s competency restoration system and the backlogged state hospital.

(KXAN Photo/Chris Nelson)

As long as a person with pending charges remains on the waitlist, or in the state hospital getting treatment, their case remains at a standstill. A recent Austin shooting spree underscores the problem.

Victims and family members have already waited over year for justice following the December 2023 rampage that left six dead and more injured across Travis and Bexar counties. Shane James, the suspect charged with multiple counts of capital murder, awaits trial. When that might happen isn’t clear. He was declared incompetent to stand trial in November, when there were over 500 people ahead of him waiting an average of 245 days for a maximum security state hospital bed, according to HHSC records.

But just getting to the state hospital doesn’t mean a person will be restored to competence. The murder of Clara Oda Torriente-Capote, a 36-year-old mother, provides a prime example. In 1999, she was stabbed and killed in the parking lot of a South Austin gas station. James McMeans, a 30-year-old man who was homeless and diagnosed with schizophrenia, was soon charged with her murder.

McMeans was sent to the state hospital in 2000, and he is still there 25 years later, according to court records. During that time, the courts have extended his commitments repeatedly, records show.

While the number of people on the waitlist ballooned in recent years, HHSC officials have worked to reverse the trend.

HHSC investment

“Due to our efforts and the support from state leadership, we have seen a decrease in the number of individuals on the maximum security and non-maximum-security waitlists, as well as a reduction in the overall time people are on the waitlist,” an HHSC spokesperson told KXAN by email.

After the onset of the pandemic, when the waitlist and wait times skyrocketed to record levels, HHSC officials acknowledged they had removed state hospital beds from use due to low staffing.

In 2023, lawmakers set out $1.5 billion for seven state hospital construction projects that are part of renovations begun in 2017 that will add 618 hospital-owned beds, including 384 maximum security ones, according to HHSC.

HHSC has also received funding for 166 inpatient psychiatric competency restoration beds it wants to have online by the end of fiscal year 2025. To improve staffing, the agency has offered employment incentives, raised base salaries and provided flexible shifts. Those efforts have led to an increase in state hospital staff to 7,550 in January, compared to 5,900 two years prior, HHSC said.

All those efforts have pushed the waitlist curve down. Nevertheless, there were over 1,700 people waiting for a state hospital bed in December. That’s far too many, according to Eckhardt, who filed Senate Bill 719, directing HHSC to conduct an extensive study of state hospital beds. The study would dig into the availability of beds for inpatient services; the makeup of the population using state hospital beds including intellectually disabled people; projected needs in the coming years; anticipated resources and more. The bill was referred to the Senate Health and Human Services Committee on Feb. 7.

Eckhardt said the state should be tracking deaths, too.

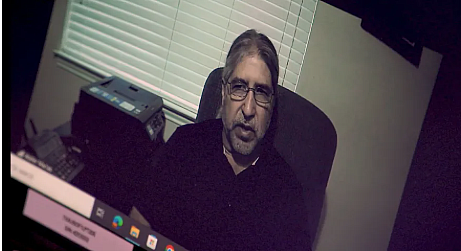

Walter Macias, whose brother Fernando died while waiting for a state hospital bed, hopes state leaders will act after hearing his story.

(KXAN Photo/Chris Nelson)

Tracking deaths and other impacts of the state hospital backlog would expose the need for investment. The “price tag on the state would be hefty,” she said. Letting localities – like counties, hospital districts and cities – absorb the cost has been easier for the state than footing the bill.

“I think the state isn’t tracking it because they’re afraid to know,” she said.

The study in Eckhardt’s bill would provide even more information on top of the November state audit, which unearthed an array of troubling issues.

Time outs, deaths, and missing paperwork

The state audit focused on Texas’ competency restoration system from September 2018 to December 2023, when over 15,600 people were placed on the waitlist.

Extended wait times have led 168 individuals on the waitlist to be “timed out” of jail, auditors found. That means those people were waiting for a state hospital bed so long they reached the maximum possible sentence for the charge they faced and had to be released despite not being convicted or treated.

Auditors also discovered the process for handling competency cases varies widely from county to county and can affect how quickly cases are resolved. For example, Harris, Tarrant and Travis counties have a dedicated docket for competency-related cases, unlike most other counties.

And, auditors uncovered a raft of administrative and paperwork issues originating in counties.

When a person is found incompetent to stand trial and a court orders them to get competency restoration in a state hospital, the court is supposed to send the commitment order to HHSC immediately. Once HHSC gets the commitment order, the person can be placed on the waitlist. Auditors found that isn’t always happening. Less than half of commitment orders were sent to HHSC the same day as required, and 4% were submitted over a month late. In one case, auditors discovered an individual’s commitment order wasn’t reported for over two years to HHSC for placement on the waitlist.

Separately, state law requires district and county clerks to report information on certain individuals found incompetent to stand trial to the Texas Department of Safety within 30 days. DPS passes the information to the FBI for federal firearm background checks. Auditors found clerks’ offices across the state failed 830 times to make those reports, which could make it possible for one of those people to potentially purchase a firearm without getting flagged on a background check, according to the audit.

Auditors also found that local programs meant to divert individuals from the waitlist are under utilized.

Texas has 254 counties; 43 of them have outpatient services, 20 counties have jail-based programs, and 14 counties have both.

Just 6% of those waiting, or about 950 people, were removed from the list after their competency was restored through an outpatient or jail-based restoration program, according to the audit.

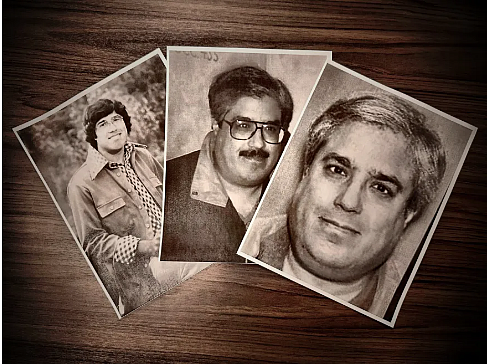

Fernando Macias struggled with mental health issues for nearly all of his adult life. In 2018, he died in Bexar County custody. He had been found incompetent to stand trial, and his health deteriorated in jail.

(KXAN Photo/Josh Hinkle)

If the state can study the system closely – outcomes, deaths, costs and future needs – it can get a better handle on what needs to be done, Eckhardt said.

“I think regular tracking is absolutely essential,” Eckhardt told KXAN. “If we want to wrap our arms around the escalating costs at the local level, if we’re going to blame the locals for coming up with solutions that cost property tax dollars, maybe we should take a look at ourselves first to see what kind of investments we’re making at the state level.”

The state audit’s finding of at least 54 people dying while waiting for a state hospital bed since fall 2018 further illustrates the need for a study, she said.

“It’s really tragic that people are dying while waiting for care,” Eckhardt added. “Now, again, we don’t know the causal relationship between their death and their psychiatric circumstances, because we’re not studying it.”

Graphic Artist Wendy Gonzalez, Investigative Photojournalist Chris Nelson, Digital Special Projects Developer Robert Sims and Digital Director Kate Winkle contributed to this report.