Lethal and lawless

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Sara Israelsen-Hartley, a participant in the 2019 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

How looking at an invisible gas could bring change into your home

Inside the newsroom: Ignore radon testing at your own peril

10 ways to protect your family from radon

The radioactive killer

From deadly mines to dangerous bedrooms

Steve Griffin, Deseret News

Editor’s note: This investigative report was produced with support from the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship.

SALT LAKE CITY — In a small cubicle on the fourth floor of a beige government building, seven TRAX stops west of downtown, one woman is on a mission to save lungs.

She wants every Utahn to know what radon is, how dangerous it can be, and what they can do about it.

But the first and biggest hurdle is navigating her own lawless state.

Utah has no meaningful regulations for the carcinogenic gas that’s produced as uranium breaks down in the soil, then seeps into basements and ground-level floors, posing a health hazard to anyone breathing it.

Yet Eleanor Divver, Utah’s radon project coordinator, has seen states like Minnesota, Illinois and Maine pass laws that are making a difference. These states and others have created policies that impact residents at crucial junctures like new home construction, home sales and school classrooms — potentially saving lives.

But here in Utah, Divver can point out a string of gaps in the system — holes that keep families at risk.

Building out the enemy

Today, for usually less than $2,000, certified radon professionals can get most houses to a safer radon level by sealing cracks in the foundation and adding a ventilation system.

But it’s highly recommended and cheaper — around $400-$800 — to build homes in ways that prevent radon accumulation in the first place.

It requires builders to take a few extra steps during initial construction to “rough out” a ventilation system to help radon escape through the roof, not pool in the basement. Active systems contain a fan that runs 24 hours a day, while passive systems rely on natural air flow, but can be updated with a fan if needed.

Connecticut, Illinois, Minnesota are the only states with statewide requirements for radon-resistant new construction or RRNC.

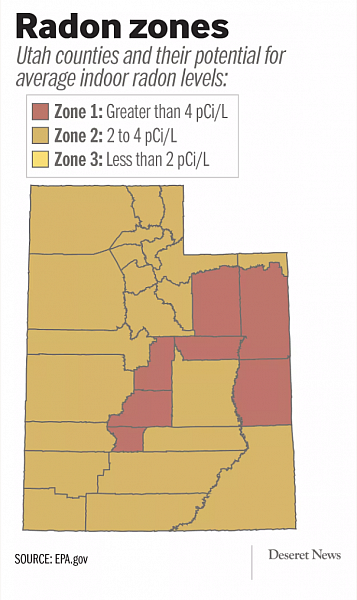

A handful of states including New Jersey, Michigan, Oregon and Iowa require builders to build radon-resistant, but only in certain cities or counties, some designated by the EPA as potential high-risk zones for elevated indoor radon levels — of which Utah has seven. The rest of Utah is zone 2, or moderate potential risk.

Ross Ford, executive officer of the Utah Home Builders Association, said he knows some Utah builders install passive systems proactively, but couldn’t specify exactly who, as it’s not something the state or the association tracks, though he admitted it would be a good idea.

There are a few companies building RRNC:

- Knight West Construction in Orem mitigates for radon because it’s part of “building green.”

- Blackdog Builders, a custom home builder in Park City, says almost no buyers turn down their offer of a radon system installed as part of a new build or a major renovation project.

- D.R. Horton, one of the top three homebuilders in the state based on number of homes built, began installing active mitigation systems in 2003 after learning about the health risks of radon exposure.

- McArthur Homes has been installing passive systems for several years to proactively address a radon problem it was seeing in some of its finished homes.

Ivory Homes, the largest builder in the state, said its employees talk with homebuyers during the contract process about radon and what it is, but don’t automatically put in a passive system, leaving that to buyers’ choice.

While some builders may rough out the systems correctly, certified radon mitigator and radon educator John Seidel said he encounters 60 to 70 new Utah homes each year where the new-construction work was done incorrectly — requiring a costly overhaul before the radon system could be activated, or even an entirely new system.

Seidel would love Utah’s code changed back to what it was pre-2017 — when radon-resistant new construction systems had to be installed by certified radon professionals, not just general contractors — but short of that, he’d like a state inspection process for RRNC to mirror what’s done for electrical work or plumbing.

Michael Siler, president and CEO for the Utah Radon Coalition, wants to go even further, requiring a state inspection of any radon system, whether it’s in a new build or an existing home.

In Maine, anyone who works in the radon industry is required to be licensed by and submit their testing data to the state, as well as take continuing education courses, said Jon Dyer, Maine’s radon coordinator. A yearly fee for radon professionals, ranging from $75-$150, helps in a small way to fund the state’s radon program, and Dyer also follows up with any mitigation system complaints to protect homeowners.

However, some Utahns worry another inspection will slow down the homebuilding process and dissuade builders from altruistically building RRNC.

“We shouldn’t make it onerous or difficult for those who want to build a better home; don’t give them a reason to not do it,” says Ron McArthur, president of McArthur Homes.

He believes in the importance of passive systems, but knows that builders’ budgets are tight, and every dollar spent “kicks someone out of the ability to buy a home.”

When McArthur started more than 25 years ago, he could get a family into a home for less than $100,000. Today, he can’t even buy a lot for $100,000 and can barely get families into a townhome for less than $300,000 along the Wasatch front.

For him, getting families into a safe, warm place to live takes precedence over secondary concerns about a gas that may or may not be a problem for them.

Silence during sales

Experts agree that buying a home is another great time to talk about radon.

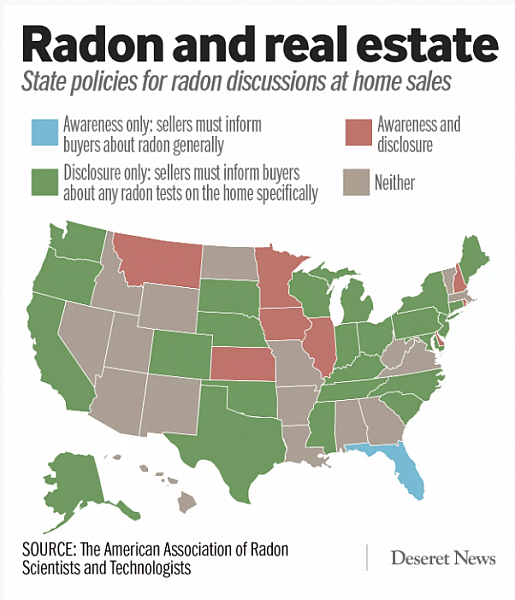

Seven years ago, Minnesota passed a law requiring that home sellers provide buyers with a state-authored radon warning statement, as well as information about any radon tests done on the property.

They didn’t require that people test their homes — just talk about radon.

Since the law passed, the number of mitigation systems installed each year has jumped from around 1,000 to more than 4,000, says Daniel Tranter with the Minnesota Department of Health.

In Utah, radon is usually mentioned twice during a home sale: once in the Utah Association of Realtors’ seven-page seller’s disclosure document, lumped with other hazards like “asbestos, lead-based paint, buried storage tanks and methane gas.”

The second reference is on the front page of the association’s buyer due diligence document, added in 2014 as a way to support SB 109, which allocated $25,000 for a statewide electronic radon awareness campaign.

It warns that elevated radon levels are linked to lung cancer and advises buyers to “consult with appropriate professionals” to gauge their potential risk.

Real estate agents in Utah should hear about radon during their 120 hours of required instructional classes; however they’re only tested on their ability to define it and state the EPA action level. Once certified, there are nearly a dozen continuing education classes on radon, but they’re only a few of the many core class options, meaning agents could choose something else.

Home inspectors might suggest or include a radon test as part of their inspection, but it’s not required and it’s often at extra cost.

Utahns can get their own radon test kit for $11 through radon.utah.gov. Those in other states can visit epa.gov/radon.

For lower-income families buying a home in rural Utah (anywhere outside of Salt Lake, Davis and most of Utah county), the USDA offers low-interest, single family direct home loans.

While USDA officials can’t suggest a radon test as part of that transaction, they can conduct one if requested and mitigate if needed, using loan funds, says Lori Silva, USDA housing program director for Utah.

If Utah were to require a radon test be part of every home sale, it would automatically allow Silva to test all the homes the USDA works with here and fix those that need it — covering “a lot of families.”

Colorado has found another way to help families and is currently the only state with a low-income radon mitigation assistance program.

Since January 2018, state-contracted providers have fixed 93 homes with 14 in process — at no cost to the families who qualify, based on income. The program is funded by the state hazardous substances response fund and is sustainable.

Cancer in the classroom

Because radon is a long-term risk, and children spend significant time at school, the EPA recommends that all schools test for radon. National data shows 1 in 5 schools will have at least one classroom with elevated levels.

That’s still just a recommendation, and Utah has done nothing to advocate for or advance radon testing in its schools.

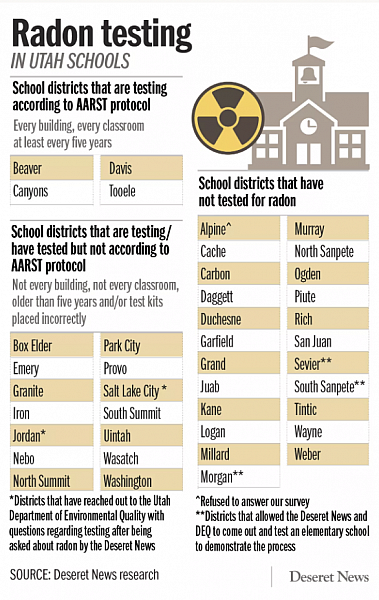

The Deseret News surveyed Utah’s 41 school districts, asking superintendents, maintenance facility managers and building supervisors about their radon awareness and testing.

We found:

- Out of 41 districts, 18 said they had tested for radon, while 23 hadn’t or weren’t sure.

- Of the 18 districts who said they had tested, only 4 districts were testing according to recommendations from EPA and the American Association of Radon Scientists and Technologists — meaning they had tested every classroom in every building within the last five years, or they test every classroom on a ongoing, rotating basis. Testing every classroom is important because levels can vary within a building.

- A few districts were aware of radon and had voluntarily taken steps to test, but had tested only a few buildings, or only a few classrooms, or placed test kits in incorrect locations such as boiler rooms or closets.

- In Utah’s seven high-risk counties, the school districts either hadn’t tested (seven) or hadn’t tested correctly (one).

- Very few districts knew that if high radon levels were found in their schools, most situations could be remedied by adjusting HVAC systems to increase the air flow.

None of this means schools are purposely ignoring radon. In fact, when we asked districts why they hadn’t tested, 10 said they didn’t believe radon was an issue facing their district. A significant number were unsure how to test and where to start. Many were simply unaware of radon.

“The No. 1 hurdle we have with radon is the same hurdle that I have with everything in my job — communication, just making people aware,” said Cade Douglas, superintendent of the Sevier School District, about three hours south of Salt Lake.

Following the survey, the Deseret News partnered with Divver to work with districts like Douglas’ that were curious about the radon testing process.

We tested elementary schools in the Morgan, Sevier and South Sanpete school districts following AARST protocol: testing every classroom and area where students might spend significant amounts of time.

Out of 108 test kits across three schools, nearly all results came in below 2 picocuries per liter, with five tests coming in above 2, the highest at 2.6 — something to retest and monitor, but still below the 4 picocuries action level recommended by the EPA.

While no significant HVAC adjusting was needed, administrators said they appreciated the opportunity to learn about radon and share information with staff and parents.

After our conversation, Douglas said he went out and purchased a test kit for his own home.

Canyons School District, on the east side of the Salt Lake Valley, has been testing consistently for the last 10 years, because it’s the “right thing to do,” said Kevin Ray, risk management coordinator for the district.

The district has built in $7,000 annually to cover test kits for its 45 buildings, testing rotating classrooms each year. When areas have come back high, Ray has adjusted the HVAC system and then retested — with only a slight bump in electricity costs.

Currently, there is no funding, training or education for radon testing in Utah schools.

Other states have solved the problem by providing mini grants, like in New Jersey, where its Department of Environmental Protection, Radon Section, provides up to $2,000 to help schools with radon testing — even though testing is not required by state law.

Oregon and Illinois both require testing of schools — Illinois every five years, and Oregon every 10, plus a plan for how to share the result data. Illinois offers online training for school employees who can become certified to test, thus avoiding the cost of hiring a radon professional, and the Oregon Health Authority created its own series of resources including training for school officials, letters to parents and the media as well as testing plans that can be adapted by any school — even those in another state, said Curtis Cude, radon awareness program manager at Oregon Health Authority.

The Utah PTA has been concerned about radon since 1998, when it drafted a resolution that resolved to inform parents about testing, encourage all districts to have buildings checked for radon and push for radon-resistant new construction in future school buildings.

Despite being updated in 2014, the resolution has remained fairly unused, overshadowed by other, louder education issues, said Cheryl Phipps, who drafted the resolution as a then-member of the health commission for the Utah state PTA.

Utah not only lacks funding and inertia for school testing, it lacks accountability.

There’s currently no database on districts’ testing status — other than the list the Deseret News compiled.

However, each year, the Utah Division of Risk Management administers an online self-inspection survey that all of the buildings insured by the state are expected to complete, said Brian Nelson, division director.

There are no radon-related questions on the survey, but after being asked by the Deseret News about radon awareness in the state, Nelson said he would be willing to “augment” the survey to add a question about whether a radon test has been conducted for a specific building or school.

“It will clearly take time to do that,” he said, “but it doesn’t mean we don’t get started, and I think this is a good start.”

[This article was originally published by DeseretNews.]