Living in the Shadows: When a New Home Means a New Diet, Health Problems Can Arise for Refugees

On a typical weekday morning, 47-year-old Tek Nepal is moving about the Mount Oliver duplex he shares with his wife, sons, daughter-in-law and grandchild.

He works nights, so he gets his family time in the mornings. And often, that time centers around eating.

Those meals used to consist of lots of starches. But since a Type 2 diabetes diagnosis last year, they have changed.

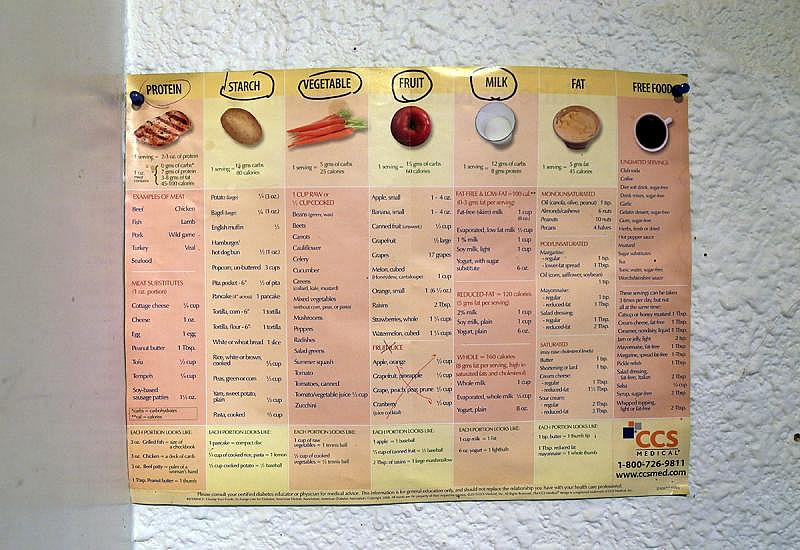

"I don’t eat rice at all. I don’t eat potatoes. I try to eat a lot of green vegetables like lettuce, spinach … carrots, and I don’t eat totally fried things," he said, showing off a chart of appropriate foods on his kitchen wall.

Nepal is ethnically Nepalese. He was resettled in California as a refugee, moved to Tennessee, then Pittsburgh, which has a lower cost of living and boasts a growing Bhutanese-Nepalese population. Before coming to the U.S., he spent 17 years in refugee camps in Bhutan.

About 4,000 to 5,000 ethnically Bhutanese-Nepalese refugees call Pittsburgh home. Having migrated in the last six years, it’s a new population that is falling into an old immigrant paradox.

Nearly 26 million Americans have diabetes, and another 79 million are pre-diabetic, up sharply over the last few decades. Included among those statistics are newer Americans, people such as Nepal who came here as refugees. According to a study published in the journal Human Biology, an immigrant’s risk of obesity and hypertension — indicators of diabetes — grow with every year they are here.

At the Squirrel Hill Health Center, a federally qualified facility that provides the bulk of initial and follow-up care to refugees, Chief Medical Officer Andrea Fox is perpetually busy. She spots trends in her patient population. Rarely do the Bhutanese come to the U.S. with a diabetes diagnosis, but they’ve found a high prevalence of the disease in those they treat.

"Sometimes they develop it once they are here, once they start gaining weight while they are here," Fox said. "And sometimes they come undernourished. So weight gain is a good thing, but sometimes they get over-nourished while they are here … like everyone else, and that’s when they develop it."

Tek Nepal prepares dry curry for that day's lunch. "I try to eat a lot of green vegetables like lettuce, spinach … carrots, and I don’t eat totally fried things," he said.

(Ryan Loew/90.5 WESA)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention monitors refugee populations. Among their priority health conditions for the Bhutanese are anemia, B12 vitamin deficiency and mental health. They haven’t been tracking diabetes numbers.

A study done earlier this year at a clinic in Atlanta looked at non-infectious diseases among Bhutanese refugees. It found high rates of obesity, hypertension and diabetes.

Nepal said as difficult as things were in the refugee camps, there was more physical activity in day-to-day life.

"It was a very big transition for us because we came from a totally different world — totally different — where everything was done manually, and then here everything is done technologically," he said.

Saraswati Bhandari, a 32-year-old refugee, also had to change her eating habits. In 2012, when she was pregnant, she developed gestational diabetes.

"For my baby and for my health I control myself," she said. "It's not that difficult. I like to eat but I control. I ate salad and then brown rice, and I controlled myself and I ate a lot of vegetables."

Now, with a healthy baby, she has kept some of those habits. Her home is stocked with fresh fruits and vegetables.

Bhandari lives in Prospect Park, a Pittsburgh community full of refugees. At the Prospect Park Family Center, Elizabeth Heidenreich, a family development specialist, does everything from accompanying refugees to doctor’s appointments to helping them read ingredients on packaged foods.

"A lot of my clients say in their country nobody has diabetes but in this country, everybody has diabetes," Heidenreich said.

Back at the Squirrel Hill Health Center, Fox said once diagnosed, some people don’t want to change their eating habits. Lacking health literacy, doctors may have to explain the function of the pancreas for example. And they may have to tell patients to take their medicine even when they don’t actually feel sick.

"The idea of having preventative follow-up visits and regular blood checks and how to refill medicines once your done with them for a month … all those concepts are kind of new that we have to teach them," she said.

And then there is the issue of health insurance. Nepal had a job that provided him coverage. And as a pregnant woman Bhandari qualified for Medicaid.

After a refugees initial medical benefits run out, if they don’t have a job that provides medical benefits or qualify for Medicaid, they may just end up uninsured. With a diabetes diagnosis, Fox said that can lead to financial trouble.

"Insulin costs about a hundred dollars a vial for inexpensive insulin,” Fox said. “If you go into some of the more expensive ones like Lantis, which is easy to administer and you only have to take it once a day it goes much higher than that. So in terms of insulin that is a real struggle to get for our patients who are uninsured."

There’s also diet. Fox said it's not as simple as refugees coming to America and subsisting on fast food and soda. There are some of the culinary traditions the refugees bring with them.

"Carbohydrates are usually pretty inexpensive, and the Bhutanese diet is usually pretty high on potatoes and rice and noodles and all of the things that are high in carbohydrates," Fox said. "So we explain to them that it isn’t that you can't eat those things, we’re not taking away those things, you just have to eat less of them."

Once they understand the risks, it is easier to change their habits, particularly because in their recent history they have had to change so many other aspects of their lives.

Since his diagnosis, Nepal has been promoted into a job that’s made him more active: He is delivering medication throughout Mercy Hospital.

"In my eight hours there, I walk like seven hours, so that helps me a lot now," he said.

A chart of appropriate foods for Tek Nepal to eat hangs on his kitchen wall.

(Ryan Loew/90.5 WESA)

He’s lost the 30 pounds he says he put on since arriving in the U.S. The weight hadn’t bothered him before, but it was the first move after escalating symptoms. He was always thirsty and had to urinate often, and then there was the health scare that led to his diagnosis.

"When I was driving and I stopped suddenly because of my blurry vision, I had to ask someone for help and they took me to St. Clair hospital," he said.

He’s also cut back on foods he loved, things like potato-stuffed deep-fried samosas.

"People in our community eat a lot of fat in the food and they like it — fried, oily, spicy, cheesy, hot everything — so now I’m out of that," Nepal said. "I only like to have the green things more."

In addition to the lost weight, he’s gotten his wife and older relatives to eat like he does now. But he does have concerns about his sons and their appetite for French fries and pizza.

"I’m trying to not have my kids have diabetes," he said. "Diabetes itself is not only one disease, it is related with the kidneys, heart, so I’m worried about my kids."

His family has been through a lot, Nepal said, and he wants them to have a better life than the one they had in the refugee camps.