Many violent young offenders were 'born into dysfunction'

This article and others forthcoming on this topic are being produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

Where Do Kids Get Guns? Inmates Reveal How Easy It Is

Fernandez case highlights the long-term implications of incarcerating youthful offenders

Arrest of 12-year-old on manslaughter charges highlights challenges in cases of kids

For many young homicide offenders, trouble easy to find

Audio: Story Behind the Story: When Kids Kill

Marcus Wilson remembers the first time he saw his mom use crack cocaine. He thinks he was about 9. "She was doing it off a soda can," he said. "To experience that, it was like, 'Mom? Are you alright? Are you OK?' ... It's kind of scary." Wilson's life as a child was defined by adversity and suffering.

Wilson's mother had an abusive boyfriend who beat her and her kids. Wilson saw his father shot. Other times his father was behind bars. The family never stayed in the same house or apartment for more than a year or two, moving from one tough part of town to another.

“My mother took drugs over her kids, and with men, she was easily manipulated and persuaded to do things like drugs," Wilson said. "My mother would always, always take her frustration out on us. … We didn’t have a lot of lights and water, supplies, food, things like that.”

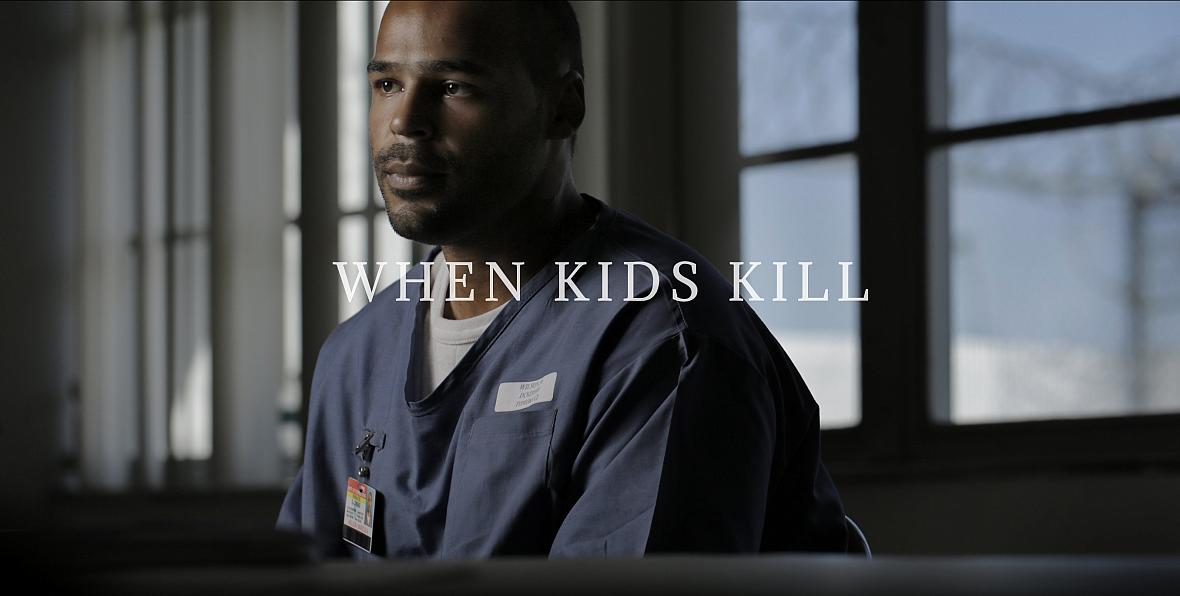

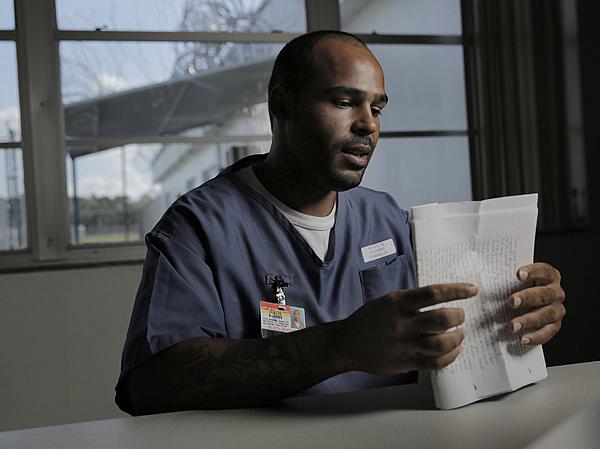

Wilson, now 28, recounted his childhood from Tomoka Correctional Institution in Daytona Beach, where he's now serving a 20-year prison sentence for a second-degree murder charge he picked up when he was 17.

Co-defendant Christopher Crockrell, 18, and Wilson wanted to get revenge on 20-year-old Freddie Lee Smith III, who, according to the police report, both teens said had stolen a gun from them.

MARCUS WILSON | “My mother took drugs over her kids, and with men, she was easily manipulated and persuaded to do things like drugs."

They donned all-black and found their victim in the Washington Heights Apartments parking lot. Crockrell shot Smith once in the head as Wilson watched. It took nearly a year for the two to be arrested.

When a kid plays a part in killing someone, the community often looks to the parents for answers — and to place blame.

But in many cases, parents don't know how to help their own kids. In dozens of letters from Duval County inmates like Wilson and those in similar situations, the Times-Union heard repeated stories of abuse and neglect at home, absent fathers, and mothers who struggled with their own challenges.

“All of the things that help people grow up and become law-abiding citizens aren’t in place in these children’s homes,” said Sara Baldwin, director of the mitigation unit for the Fourth Judicial Circuit Public Defender’s Office.

In her years of working on juvenile life without parole re-sentencing cases, Baldwin said, she can think of one, maybe two, in which her client had a stable home life.

Public Defender Charlie Cofer said, “Many of the parents are very ill-equipped to nurture children."

Not only are the parents ill-equipped, they had no one else to turn to for support. Mitigation experts have worked cases where they couldn't find a single adult relative in a teen's life who hadn't been jailed at least once.

“There is no excuse for this horrific crime, but there’s no excuse for any child in America to grow up the way he did,” said Kate Bedell, a defense attorney in one such case in 2017. “He was born into dysfunction. ... That’s the kind of dysfunction that causes these horrible cases to come up.”

Among the 25 incarcerated young offenders from Duval County who responded to a Times-Union survey developed in the reporting of this series of articles:

• 60 percent reported emotional abuse at home

• 52 percent reported physical abuse at home

• 56 percent reported emotional neglect at home

• 84 percent said they lived with someone who was a problem drinker or who used street drugs.

"It was my environment and the people around me that caused me to act dysfunctional,” said Anthony Wagner, who described seeing heavy drinking and domestic violence as a child. Wagner was 15 when he took part in killing Richard Dean Bolin, 59, in 2004. "I blame families like mine. I didn't do my homework at night because there was nobody there to help me. ... The problem isn't the children, it's the adults and the environment."

Wagner was one of the 25 who took the Times-Union survey, though more than two dozen more men shared pieces of their story but did not take the survey.

“Who else am I better to learn from then the adults around me?"

'We needed our mama'

When Deborah Wilson was in the midst of her addiction, she was “nowhere to be found” for her kids.

“He wanted to work and get money,” Deborah said of her son's tendency to borrow a lawn mower and cut grass to earn money. “He wanted to provide for himself, because I wasn’t providing for him.”

His older sister, Jasmine "Angel" Wilson, and Marcus are just shy of being a year apart in age. Because of their mom’s addiction, Jasmine did her best to take care of herself and her baby brother.

When the two were teenagers, Deborah Wilson moved out of the apartment they shared on Tyler Street between Beaver Street and Kings Road and left her kids on their own. “Marcus was out of control,” she said, looking back.

Marcus went looking for acceptance where he could get it: from older guys who let him drink and smoke weed with them. He started to hang out with a friend who became his co-defendant, who he had met at a juvenile detention program. He stabbed a kid when he was in middle school. He got his first gun at 14. He learned that he would become a father at 16.

"Birds of a feather flock together," Marcus Wilson said. "The people you are hangin’ around are the person that you become.”

His sister tried to help.

“Trying to have my own place at 16 and raise my brother was very hard,” Jasmine Wilson said. She was going to Raines High School and working at McDonald’s. Marcus Wilson said he made it to ninth grade at Raines before dropping out to work full-time at Captain D's, but his mom and sister think he only finished seventh or eighth grade, respectively.

“We needed our mama,” Jasmine said. “If my mama woulda took up for us, we wouldn’t have been like this. If she would have provided us with encouragement we needed for school, we would have made it through.”

What Jasmine didn’t know at the time was that she and her brother could have used Medicaid and food stamps because of their low income. Then he would have been able to see a doctor, take the medication he needed, and maybe he could have made it, she said.

“The situation he’s in, he’s not supposed to be there,” Jasmine said. “He was supposed to get help.”

Wilson’s mother, Deborah Wilson, is matter-of-fact when she tells her story and talks about her children. This is the life she knows, because it's what she lived as a child.

A Detroit native, Wilson said she was abused by her family, sexually assaulted, placed in foster care and got pregnant with her first child, a girl, when she was 16. As a teenager with no family to turn to and no education, she lost that baby to the state, she said.

“It’s been a hard life,” she said. “I been through a whole lot. I’m still going through a lot.”

Wilson has been off of drugs for several years now, but said she has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder, deep depression and very bad anxiety. She also has a learning disability. She said she believes Marcus has all the same conditions.

MARCUS WILSON | “I wish my mother never did drugs. The environment that we lived in, I wish we never did."

Still, she's not a believer in therapy for her or her son. She doesn't believe counselors would know how to help them.

“If you didn’t live it,” she said, “you don’t know what we going through.”

'Wish I had a different family'

The parents of many of the young offenders who corresponded with the Times-Union grew up in the same types of neighborhoods and endured similar circumstances when they were kids themselves. A few of the letter-writers shared accounts of the abuses and sexual assaults their mothers endured.

Poverty can be generational, and so can trauma. Those stresses make it hard to be a good parent, especially for people who have never seen good parenting.

Baldwin, the mitigation expert, said she doesn't judge these parents, but recognizes that they needed help that they never got. Many of her clients' parents really tried to be good parents, but didn't know how, or thought that by working two or three jobs to keep the bills paid that they were doing enough for their child.

"But the streets will claim a child that's unsupervised," she said.

Dr. Mikah Owen, a Jacksonville pediatrician, said from the time of birth on, the relationship between the baby and parent is like a dance. Social cues are being sent both ways.

“From an evolutionary and biological standpoint, the babies are using those social cues to develop their brains and learn how to respond to you. In general, you think about it as, the parents respond to the needs of their infants,” Owen said. “But really, you give an infant a certain type of parent, that infant will respond to that parent’s needs.

“So if I have an abusive parent and I cry and I get abused, I’m going to withdraw.”

That withdrawal can lead to permanent changes in the brain that affects a child’s emotional and physical well-being when they’re older, Owen said.

More than half of survey respondents said they had supportive families that were stable and dependable. At the same time, some of those same respondents would say that they faced homelessness and felt unloved at home. In their letters, few described home lives that would meet a widely accepted definition of stable and supportive.

Given the chance to explain what they wish adults had done differently, most of the answers were simple.

“Paid more attention and showed more affection and love,” wrote Emerald Barner. She was 15 and in foster care when she was arrested for the murder of Damon Johnson in 2008.

“Been more loving and caring,” said Marvin Wilson, who isn't related to Marcus or his family. Over the span of six days in January 1981, Marvin Wilson, then 16, and his 17-year-old co-defendant James Harmon carried out a spree of robberies, kidnappings and murders. Clarence Langston Jr. and Raymond Kennedy were killed by the teens, and both defendants, now well into their 50s, are decades into their centuries-long sentences.

“Try to care about me a little,” said Donald Thomas. In 1983, 17-year-old Thomas and three co-defendants, ages 16, 17 and 20, broke into the San Marco home of adult siblings Charles Acker and Anne Acker. Both Ackers were stabbed to death in bed, and all four co-defendants were given life sentences for their roles in the slaying. “I wish I had a different family.”

‘All of that happens in poor homes’

Most of the teens who wrote to the Times-Union didn’t set out to kill; they set out to find some money or something of value. Of the 13 survey participants who said their slaying stemmed from another crime or street beef gone bad, nine were for robbery, burglary or theft.

“If you show kids that drugs bring cars, money, women, and you show them that every day on TV, and you're not showing them a way to get money that right way, and they growing up and they living in them low down apartments ... ,” wrote Samuel Fagin, who did not take the survey. He was 16 when he and his uncle robbed a store on Acorn Street in 1993. The uncle, Willie Miller, fired the fatal shot at James Wallace, 60. “Mother can’t provide for the kids, get a check once a month. The father can’t get a job ...”

On a Department of Juvenile Justice assessment given to kids entering that system, 94 percent of minors arrested in connection with killings in Duval County self-reported that their family income was under $35,000 a year.

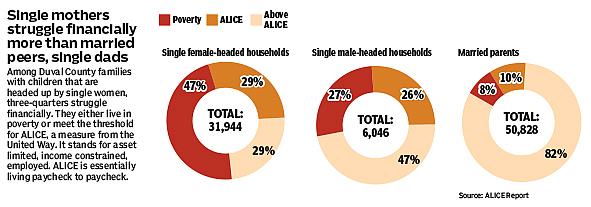

Of the 25 Times-Union survey respondents, 21 said their parents had separated or divorced. Among those who grew up in single-parent homes, their caregiver was most often their mother; their fathers were not around. They were long gone, locked up or dead.

Forty percent said someone who lived in their house went to prison, and 36 percent said a close family member had been murdered.

The men who took the survey were especially protective of their mothers, and often sympathetic to their plights. When asked to describe who was always there for them, eight of the 23 men who took the survey named their mother.

"I truly believe in my heart of hearts (that) my mother, given her circumstances, did the best she could do with having six kids to raise alone," said Tony Brown, who took the survey. Brown, now 61, was 16 when he took part in a murder of a Springfield pharmacy clerk that earned him a 15-year sentence. He came back to prison in later on an unrelated charge.