More than hunger pains: How food insecurity impacts the body

Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton’s reporting on hunger and food insecurity was undertaken as a project for the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism and the National Health Journalism Fellowship, programs of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Growing up hungry: Food insecurity’s impact on mental health

Courtesy of Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

TULSA, Okla. — The impact of regularly going without a nutritious meal goes beyond a growling stomach and a short temper.

“The best medicine in the world will not be effective if I’m treating an undernourished child,” said American Academy of Pediatrics Past President Dr. Sandra Hassink. “For pediatricians, nutrition is health and it’s a core component of health.

According to a journal article published by the American Academy of Pediatrics, both preschool and school-aged children showed that chronic hunger and food insecurity are significant predictors of health conditions, even when taking other factors into consideration.

With chronically hungry children twice as likely overall to experience health problems, the AAP formally announced in October 2015 that it was recommending its members start screening children for food insecurity by asking two hunger-related questions and as needed, provide referrals to food pantries, local WIC offices and other community resources.

Nationwide, one in seven families experience food insecurity at any given point in a year. The rates are higher in Indian Country, thus increasing the risks for the physical effects that come with poor nutrition.

Hunger’s effects on organs

The influence of not having regular access to healthy food can be felt at a young age through its effects on childhood brain growth and cognitive function.

Nutrient deficits at an early age can limit cell production, while shortages later on in childhood can inhibit a brain cell’s ability to grow and handle complex functions. Chronic hunger can also impact the brain’s chemical processes and can hamper communication between brain cells.

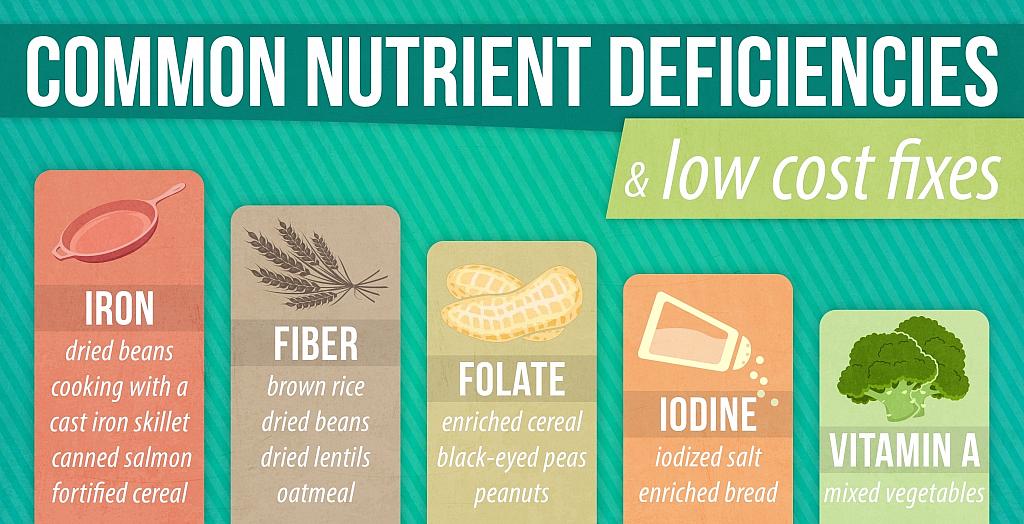

For example, iron, a nutrient often found in red meat and dark leafy vegetables, is necessary for developing not only motor skills in infancy and early childhood, but also the brain’s ability to process, learn and recall information.

Found in seafood and beef, zinc is a key component in the development of both the central nervous system and the enzymes needed to allow brain function.

“Children who are well-nourished early on have healthier brain development,” Hassink said. “They also tend to have higher IQs and stronger immune systems.”

That stronger immune system stems from regular, continued access to many of the same nutrients that facilitate brain development.

For example, a deficiency of zinc or iron can make it harder for the body to fight infection or produce t-cell lymphocytes, a form of white blood cell.

Additionally, one of the measures commonly taken to avoid hunger pains – relying on cheap, high calorie foods with little nutritional benefit – is not necessarily any healthier in the long run.

Virtually unknown in Indian Country until the 1950s, diabetes is now more than twice as common among American Indians and Alaska Natives as a whole than the general population. Once known as adult onset diabetes, the incidence rate of Type 2 diabetes among Native American youth is now estimated at almost 50 diagnoses per year for every 100,000 teens – more than double that of any other group.

Although commodity cheese is high in saturated fat, its higher quality cousins are a more nutritionally sound source of protein, calcium and vitamin A. (Photo by Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton)

Multiple studies have shown a correlation between the disease and an increased intake of corn syrup and other refined carbohydrates, a common ingredient in many low cost, shelf stable, processed foods.

Although it is not a direct cause, with higher levels of fat, sugar and salt in less expensive sources, there is also often a correlation between food insecurity and obesity, another chronic condition that disproportionately strikes American Indians and Alaska Natives, including one-third of indigenous children.

For example, three ounces of commodity cheese has 330 calories and 90 percent of the recommended daily allowance of saturated fat.

Although it has 80 percent of the recommended daily intake of Vitamin A, a single cup serving of canned commodity beef stew also accounts for almost 40 percent of an adult’s recommended daily sodium intake.

A single serving of Spam, which can be bought with SNAP benefits, has one-third of the daily recommended daily sodium intake and more than a quarter of the recommended daily intake of saturated fat.

Made with flour, salt, sugar and water and fried in either oil or lard, the average piece of frybread has about 25 grams of fat in it.

Dr. Jennifer Williams with the Oklahoma City Indian Clinic said the connection and its effects, while reversible through minor diet changes, are logical.

“This does seem counter-intuitive, but it really makes a lot of sense,” she said. “Weight gain is a pretty simple calculation. In order to gain weight, we must eat more energy than we expend.

“Weight gain is not at all related to nutritional needs.”

According to the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Minority Health, American Indians and Alaska Natives are 60 percent more likely to be obese than their non-Native neighbors. Obesity in turn, carries additional health risks, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol and increased rates of stroke and heart disease.

When calories alone aren’t enough

The physical impact of food insecurity and chronic hunger is also felt at the micronutrient level.

Speaking as part of a White House panel, Adam Drewenowski, the director of the University of Washington’s Nutritional Sciences Program, pointed out the stratification of American diets, with vitamin and mineral deficiencies showing up among families struggling to put nutritious food, especially fresh produce, on the table.

“Foods contain different amounts of calories per gram,” Drewnowski said. “The most energy dense foods are the ones that are dry: fats, sugars and refined grains. They have the most calories, but not necessarily the most nutrients.

The most common nutrition deficiency internationally, iron deficiency anemia is when the body does not get enough iron to allow it to produce hemoglobin. That in turn, limits the production of red blood cells, which means less oxygen is carried throughout the body and leads to body fatigue faster.

Over time, the heart’s additional burden of working harder to make up for insufficient hemoglobin can lead to cardiovascular problems, including arrhythmias and even heart failure.

According to a 2007 study conducted by researchers at the University of Kentucky, Native American and Alaska Native infants are at higher risk for iron deficiency anemia than white, Asian and Latino babies, thanks in part to the higher iron demands during pregnancy that are not always met.

Who’s at risk?

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, as of 2014, an estimated 14 percent of all households are considered food insecure, or struggling to consistently access adequate food.

Even higher rates of food insecurity are present among families with children, those headed by a single parent, families from rural areas and those living within 185 percent of the poverty line. Among the 17.5 million American households considered food insecure are 21 percent of all children nationwide.

The USDA’s most recent report on food security among Native households, presented to Congress in January 2012, placed the food insecurity rate at about 23 percent. That figure was based on data collected between 2006 and 2008, before the Great Recession.

The newest report on household food insecurity available through the USDA does not include Native American, Alaska Native or Native Hawaiian families in its racial/ethnic breakdown.

Separately published data, including Native families’ eligibility and participation rates in WIC, SNAP, FDPIRand the free and reduced school meal program, suggest that food insecurity in Indian Country has not dropped since the Congressional study’s initial presentation.

More nutritionally effective assistance

In recent years, changes have been made to place a greater nutritional emphasis on food provided through government funded nutrition programs.

Along with more whole grains and reduced sodium content, school cafeterias are now required to offer fruit options other than juice at lunch and a variety of vegetables through the course of a week.

A member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina, Lauren Ashley Locklear participated in the free and reduced lunch program growing up in rural Robeson County, North Carolina. Her son, Brennan, started school in August and like most of his pre-kindergarten classmates, qualified for the program.

Although commodity cheese is high in saturated fat, its higher quality cousins are a more nutritionally sound source of protein, calcium and vitamin A. (Photo by Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton)

The changes on her son’s cafeteria tray compared to the ones from her childhood caught her attention pretty quickly, but for a good reason.

For many SNAP and WIC recipients, increased access to nutritious food has come from a source close to home: the local farmers’ market.

Provisions have been in place since the mid 1990s to allow farmers’ markets to accept SNAP benefits. As of fall 2015, more than 8,500 farmers’ markets nationwide now accept SNAP benefits, an increase of more than 75 percent over the last two decades.

In 2014, the most recent year for which data is available, 362,477 households nationwide made at least one purchase at a farmers’ market using SNAP benefits.

A similar program, albeit on a smaller scale, is also offered for WIC participants in 36 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands and through six tribes in Oklahoma, New Mexico and Mississippi.

With more sites now accepting EBT benefits, the number of SNAP redemptions at farmers markets has jumped by 350 percent from 2009. To further incentivize and facilitate buying fresh produce with SNAP benefits, about 500 farmers’ markets nationwide offer some kind of “double up” program, providing either a dollar-to-dollar match up to a certain limit or more along the lines of “buy $5 worth, get $1 free.”

Darcy Freedman, an associate professor of applied social sciences at Case Western Reserve University’s Prevention Research Center for Healthy Neighborhoods, has been studying food security for 15 years, including the use of government EBT cards at farmers’ markets in both Ohio and South Carolina.

Over the course of her research, she noticed that SNAP recipients who were able to stretch their benefits to include more fresh produce often took advantage of the opportunity and reaped the physiological benefits.

FDPIR recipients are also seeing more nutritious foods being offered at distribution sites.

A 2008 report to Congress notes that the average FDPIR package meets several of the nutritional benchmarks, including the recommended daily allowance for 19 essential nutrients. More distribution sites have fresh or frozen produce options instead of canned only, and the program has eliminated shortening from the list of options available. Steps are also being taken to make bison and other traditional foods available through distribution sites.

Even with the changes in federal assistance programs, the data over the years on health conditions related to food insecurity is hardly shocking to many in Indian Country.

“Just look at the diminishment of our ability to feed ourselves in terms of the health implications, especially diabetes and obesity,” Elizabeth Hoover said.

A Micmac and Mohawk assistant professor of American and Ethnic Studies at Brown University, Hoover specializes in food sovereignty, or the right to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and the right for groups to define their own food and agriculture systems.

With many tribes losing access to traditional food sources over the last two centuries, the connection between food insecurity and physical health in Indian Country comes as no surprise to her.

[This story was originally published by Native Health News Alliance.]

Photos by Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton and Lauren Ashley Locklear/Native Health News Alliance.