Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton

Freelance reporter

Freelance reporter

Freelance reporter based out of Tulsa, Okla. Regular clients include the Bigheart Times, Mvskoke Media, Native Oklahoma magazine, Osage News, Reuters and Tulsa World.

An estimated 755,000 people would lose benefits over the next three years if the rule change proposed by the USDA goes into effect.

Federal officials told tribal leaders in January they cannot exempt Native Americans from Medicaid work requirements. Tribes strongly disagree.

Trump's new budget wants to replace a portion of food stamp benefits with a box of "shelf-stable" items. For Native families who have endured such government-issued provisions in the past, that's a horrifying prospect.

For a reporting project on food insecurity in Native American communities, finding the data was the easy, writes Lenzy Krehbiel-Burton. But finding families willing to talk candidly about the problem was much harder.

With American Indians and Alaska Natives qualifying for federal nutrition assistance programs at higher rates, several tribes are trying to improve food access while providing an economic stimulus for their communities. That can mean new grocery stores, or lower taxes on produce.

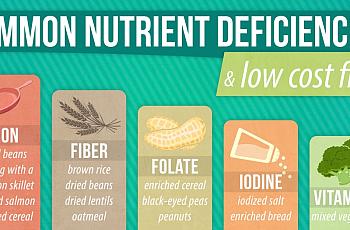

Nationwide, one in seven families experience food insecurity at any given point in a year. The rates are higher in Indian Country, increasing the risks for the physical effects that come with poor nutrition.

“If you’re not able to provide food, it makes it difficult to feel like you’re living a dignified life,” researcher Darcy Freedman said. “It’s a basic need and the mental health implications are very real. ‘If I can’t provide food for my kids or partner, who am I?’”

For many contemporary Native American communities, accessing healthy food in any form is a challenge. While the federal government offers some assistance, it's often not enough. For my fellowship project, I'll investigate what resources tribes are using – or not – to address food insecurity.