No car, no care in Coal Country

Binghui Huang wrote this series as a project of the National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of the University of Southern California's Annenberg School of Journalism.

Other stories in this series include:

What's being done about the doctor shortage in Pennsylvania Coal Country?

Travis Litts walks past an abandoned business along East Ridge Street in Lansford. He is one of Pennsylvania's many rural residents cut off from mental health and addiction treatment because of limited public transportation.

(Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

In Pennsylvania Coal Region, many are forced to travel long distances to get the health care they need.

At a busy crosswalk in downtown Allentown, Travis Litts pulls a couple crumpled prescriptions from his pocket and shows them to a few strangers. He’s hoping they’ll throw him a couple dollars so he can buy medicine to keep his heroin cravings away and manage his severe anxiety symptoms.

Litts was discharged earlier that day in May 2018 from a hospital in Philadelphia, where he was treated for a mental breakdown.

The bus could take him only as far as Allentown, 40 miles short of his home in the Coal Region.

Each moment without Suboxone brings horrible heroin withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety and restlessness, diarrhea and a runny nose.

Litts is stuck. No money. No car. No medicine.

That day, he bums enough money to get what he needs, and his father agrees to drive him home to Lansford, a hilly borough of fewer than 4,000 people in Carbon County, where he lives with his fiancee.

He’s accustomed to being stranded. Without reliable transportation, it’s hard for him to get to and from the various doctors he sees, some of whom are more than an hour’s drive from Lansford.

Travis Litts smokes a cigarette on a walk in Lansford. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

In vast stretches of Carbon and Schuylkill counties, it’s hard to get by without a car. In hollowed-out towns that dot the landscape, that leaves people like Litts cut off from the help they need to get better.

Many in Pennsylvania and across the country face the same predicament, leaving them vulnerable to worsening mental and physical health problems. Not only do they live far from the services they need, but they lack the means of reaching them.

A 2005 study by the Wake Forest University School of Medicine found that in the mountainous counties of North Carolina, a driver’s license made a big difference in whether people received the care they needed for chronic ailments. A glimpse into Litts’ situation drives home the point.

For him, a trip to the doctor’s office is a puzzle that requires careful planning, huge chunks of time and help from friends or family.

At 32 years old, he is coping with a long list of mental and physical health problems, some of the worst being heroin addiction, anxiety and depression. His drug-fueled benders have landed him in jails and emergency rooms. Without regular therapy sessions and a consistent regimen of medication, Litts’ problems compound, until he hits a breaking point and ends up in the emergency room. That’s happened dozens of times.

Just under 6 feet tall, Litts has a slight hunch that makes him appear shorter. Months ago, his clothes were hanging on his thin frame, and his closely shaved blonde hair drew attention to his gaunt face. But his weight fluctuates as he changes medication. And so do his moods.

He can go from analytical to angry to apathetic to empathetic in minutes. His powerful anti-anxiety medication tempers his mood but can make him appear sedated. He hates it when people mistake the effects of his prescription drugs for illicit drug use, because he’s working hard to get better.

He’s deeply self-reflective, quick to take blame for his poor decisions. But he’s also aware of greater problems outside of his control: the lack of jobs in his town, the skeletal transportation system and the mental health problems that have plagued him since his teenage years.

Travis Litts walks down East Snyder Avenue in Lansford. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

In Lansford, there are no drug treatment facilities, halfway homes, counseling offices or psychiatrists for him. Litts needs to go out of town to get care. And each trip to a hospital, doctor’s office or pharmacy tests his survival skills.

So he ends up begging strangers for help, or asking friends for favors. But mostly going without.

Things may change this year when Fountain Hill-based St. Luke’s University Health Network opens a clinic a short walk from Litts’ Lansford apartment.

For Litts, every day feels like a heavy burden. For Keith Enlund, who is 33 and facing similar demons, life in the Coal Region isn’t such a grind.

Like Litts’, Enlund’s problems started in high school when he began misbehaving. Both have spent most of their adult lives on drugs and recently became serious about sobriety. Both have been in and out of jail, which is where they met around four years ago when they were in for drug-related crimes.

Unlike Litts, Enlund has a strong support system. And he’s got a ride.

That’s important because Enlund lives in an isolated pocket of Carbon County, far from the many health services he needs to get better. Albrightsville, a town of about 200 people, is a 30-minute drive to almost anywhere.

But Enlund is getting to drug and alcohol counseling, therapy, daily recovery support group meetings and doctor visits because he has a way to get to his appointments. His parents drive him everywhere, often multiple times a day.

Having a ride gives Enlund a chance at a better life.

For the first time in as long as Enlund can remember, he wakes up looking forward to his day. That’s a huge change from years of waking up but wishing he never did.

He has no job, is accumulating bills and has a hard time keeping up with his fines. He’s on disability for his mental health problems. And while his check covers rent and some bills, it isn’t enough to buy staples after the food stamps run out. He wants to prioritize his health, but he can’t surmount the daily obstacles that get in his way.

“I’m doing everything. And it’s getting to the point where I’m so stressed out that I can’t handle anything else on my plate,” he said.

Some days, he wishes he could be in a group home, focusing on his recovery.

Litts and Enlund both hit rock bottom in the last two years. For Enlund, it was crawling out of a crashed car, stick thin and high on meth and heroin. For Litts, it was losing custody of his son and hitting his former girlfriend when he was high in an Allentown hospital nearly two years ago. His criminal record also includes a guilty plea for endangering his son when he left him unsupervised.

“It crushes my heart. I haven’t heard his voice, touched him, nothing, anything,” he said last fall, adding that the boy, now 4 years old, lives only a few blocks away.

During the summer, Litts saw the boy through a screen door, but the image was blurry because of his poor eyesight. Before Christmas, his former girlfriend agreed to let him spend a few hours with his son.

Enlund, too, is working to repair his family relationships.

His parents drive him to various appointments: 40 minutes to drug and alcohol counseling in Stroudsburg, 40 minutes another way to his orthopedic doctor in Wilkes-Barre, Half an hour to his therapist in Palmerton, and 20 to 30 minutes to his addiction recovery support group meetings in Jim Thorpe, Lehighton, Palmerton or farther.

His dad drives him during the day in an old truck with broken air-conditioning. Enlund doesn’t mind the hot car, but the bumpy rides make the back pain he’s had since the accident even worse.

The distance also frustrates him because it takes up so much time.

“My mom drives me everywhere; she’s got no life,” he said.

Enlund wears an engraved bracelet, a Christmas gift from his mom that reads: “To my son, always remember you are braver than you believe, stronger than you seem, smarter than you think and loved more than you know, love mom.”

After his accident, his parents rushed to his bedside.

Keith Enlund shows off the bracelet that his mother gave him. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

When he was allowed to serve a 30-day sentence under house arrest because of his fractured back, his parents used hundreds of dollars of their fixed income to install court-ordered security measures in their Albrightsville home. His mom pays his court fines.

Not only is he grateful to his parents, he’s inspired by them.

“My mom is an amazing woman, and I just want to be an amazing person as well,” Enlund said. “I’m tired of being a scumbag and being known as the drug dealer. I want to turn things around.”

Joanne Enlund, or JoJo to her family, is fighting to keep her son well after losing a brother to addiction.

Like her son, her brother lied, stole and went to jail. She bought him a plane ticket home once, but he traded it for money. So when he again called to say he desperately needed money, she said no.

He died not long after that call.

“The next phone call I got was from a coroner. And I had to tell my parents my brother was dead,” Joanne Enlund said. “And I swore — because for years, everybody kept saying ‘tough love’ — don’t tell me tough love. I did tough love once in my life and my brother came back in a box.”

So, she’s holding on tight to Keith, who’s been sober for almost a year, the longest he can remember since he was a teenager.

She wishes there were services closer to Albrightsville, but she’s willing to do whatever it takes for Keith to get better. She feels lucky that she can drive him to his daily meetings.

“I really thought I was going to bury my son,” she said.

While Keith is at his nightly meetings, Joanne Enlund sits in the car and reads Danielle Steel romances and James Patterson thrillers. She’s read “Fifty Shades of Grey” twice. She’s on book 40? 42? She’s lost count.

Joanne Enlund stands outside of her vehicle as her son Keith attends his addiction recovery support group meeting in Lehighton. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

She’s put on hold her retirement dream of spotting whales on a windy Alaskan cruise. But she’s getting to know her son for the first time in more than a decade, without drugs getting in the way. He’s not the guy who lied and stole from her, who ruined Christmas or who crawled out of a car at about 130 pounds.

As a child, Keith wasn’t as popular as his older brother or driven like his younger sister, something Joanne Enlund believes made him to turn to drugs. But he’s always been thoughtful and perceptive, albeit insecure sometimes, and able to read subtle body language. Years of drug use, she said, stunted his personal growth.

“He’s got a lot of strengths. He’s only learning them,” she said.

With each step toward recovery, Enlund is becoming more open and connected to his parents. It’s something that still catches his mother off-guard, as it did recently after she took him to a meeting.

“Keith said, ‘Mom, thank you for bringing me,’ and I said, ‘You’re welcome,’ ” she recalled. “And he said, ‘I love you, Mom,’ and I busted up crying.”

Love from afar

Litts’ relationship with his parents is more strained and tenuous.

His mom, Carla Litts, lives about an hour away near Allentown and works part time, so she can’t help him in a pinch. Through the years, she’s bought him countless phones, clothes, antibiotics, Suboxone, she said.

She’s doesn’t really know how to help him anymore. And she’s tired of disappointment.

“I just wish he could understand that if he looks in the mirror and he doesn’t like what’s going on, then it’s real changeable,” she said.

The last time she invited him to a church event, he nodded off, she said. That could have been because of prescription drugs. Who knows, she said.

Litts has several prescriptions to manage his mental and physical health problems. Sometimes he plays with the dosage, taking more than he needs.

When that happens, he finds himself short, as he did a few months ago.

Standing on a chair, Litts popped loose a ceiling panel and pulled out a shoe box.

Travis Litts stands in his bedroom at his Lansford apartment while holding clothing and medical paperwork. (Photo Credit: Rick Kintzel/The Morning Call)

He shuffled through the grab bag of things: a framed photo of an old girlfriend, some cigarettes, loose papers and a pack of Post-it notes. He reached at the bottom for medicine bottles and shook out the pill halves that have been keeping his heroin withdrawal symptoms at bay.

“I’ve been cutting them to make them last,” he said.

He needed a Suboxone refill, which is ready at a pharmacy 12 miles away in Lehighton. There’s no bus to get there. And a walk along the winding mountain roads would take him more than four hours, each way. Plus, it’s dangerous.

Sometimes he’ll pay his father to drive him to a doctor’s appointment. But his father is also sick, making him unreliable.

He can’t rely on his mom, either.

“When I’m doing well, she’ll help out. She’ll come around, like once a month. She’ll visit and buy us things. She bought us some things for the apartment because she knows we’re doing well,” he said. “Times in my life when I’m doing bad, she doesn’t. She loves me from a distance, but she doesn’t talk to me much.”

Decades of drug use have burned his relationships with his family and friends, so favors don’t come easy. His shoes offer proof of the many miles he’s logged on foot. Pulling out his sneakers from under a chair, he puts two fingers through holes in the bottoms.

“I’m still trying to deal with life on life’s terms. You see what I’m saying? And living in this area isn’t helping me,” Litts said. “I don’t have the resources that I need at all.”

Widespread problem

Getting to a doctor’s appointment is simple enough for people who live in or near cities. But rural residents who don’t have cars feel cut off from vital services.

Dr. Gregory Dobash, a St. Luke’s primary care physician in Tamaqua, said many of his patients can’t afford a car or don’t have a license. About 20 to 25 percent don’t show up for their appointments, he said, often because they have no ride. And it’s common for people to reach his office, one of St. Luke’s rural health centers, on foot or by bicycle.

A few years ago, Dobash overheard a man bartering for a ride at an emergency room in Wilkes-Barre.

The currency? Percocets.

“There’s your lack of transportation. There’s your opioid problem,” Dobash said.

Dr. Gregory Dobash at a St. Luke's University Health Network clinic in Tamaqua. (Photo Credit: Binghui Huang/The Morning Call)

In rural swaths of Pennsylvania, transportation problems are affecting people’s health, said Dr. Lauren Hughes, Pennsylvania’s deputy secretary for health innovation.

Not only do people have a hard time getting to doctors but emergency services can be delayed. For example, if multiple emergencies are occurring at once, patients may have to wait.

“Say that you have a chronic disease that is particularly active, like diabetes that’s not under control or congestive heart failure that’s not under control, and then you’re not able to get health care to monitor it, that will most certainly contribute to health challenges,” Hughes said.

There are limited public transportation options and programs for people to get around, but they are hit or miss, Hughes said, and they don’t provide enough flexibility.

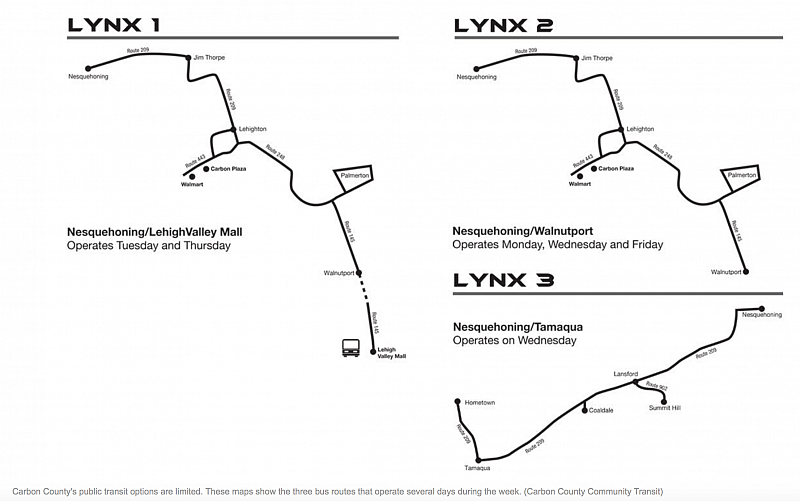

The public transit system in Carbon County, the Lynx, has three bus routes that operate one to five times a week, with stops miles apart.

Only one route runs through Lansford, connecting it to Nesquehoning and Tamaqua. That route only runs on Wednesday.

For Litts, the bus isn’t much help.

Paratransit offers a door-to-door government-sponsored ride share for seniors, physically disabled people and Medicaid recipients going to the doctor. Others must pay full fare, which can run from $21 to $50, depending on the distance.

In recent years, LANTA has received many applications from people with mental health issues, said Owen O’Neil, executive director of LANTA, which operates the system. But the transportation funding tied to the Americans with Disabilities Act was not intended to help people with severe anxiety or other mental health conditions.

“We always try to say it’s not a medical thing, it’s a transportation thing,” O’Neil said. “Can you physically not get to the bus?”

About 6,000 people ride the Lynx each year. But more than six times that amount use paratransit in Carbon County, a number that has declined significantly because of tightening rules for medical assistance transportation. For those eligible, paratransit is a big help. But because of all the pickups and drop-offs, it’s not convenient, and one trip can take the whole day.

“You’ve spent half the day or more than half the day for this one doctor’s appointment, which probably lasted 10 minutes,” O’Neil said. “It’s hard.”

Cabs and shared ride services such as Lyft and Uber are expensive options, and in thinly populated areas, people may have to wait a long time before connecting with a driver.

Some health systems are working with shared ride companies to get patients to appointments. Geisinger, for example, launched a pilot program in Scranton and Danville last spring, coordinating rides for patients through ride-share companies and public transit systems.

O’Neil said LANTA would like to offer more shared rides but there’s no money for that.

Not moving forward

Litts ended up in Lansford because his dad offered to take him in. Low rents in Lansford meant Litts could afford a place of his own.

Between taking care of his health and scraping up enough money through odd jobs to buy essentials such as food and shoes, saving money to move to a more convenient location isn’t on his list.

But it’s easier for him to trek great distances in the Coal Region than to figure out how to get from the life he lives to the life he wants.

“This is a nightmare, but I’m used to it,” Litts said as he opened and closed his mostly empty food cabinets on a late September day.

The pasta in the refrigerator had spoiled, and it was near the end of the month, so his food stamps had run out.

Neither Litts nor his girlfriend, Alicia Kachmar, wanted to cook the last bag of pasta. That’s for even more desperate times.

They don’t have too many people to lean on.

“We know everybody. We can’t be around a lot of them because they are a mess,” Litts said.

He opened up a social media app and pointed to names: Drug addict. Drug addict. Meth. Cocaine. Heroin. She’s homeless. He’s in jail, he said as he went through the list.

Litts says he wants to be a better man. To that end, he’s memorized Bible passages and recites them over and over, especially when things seem to be falling apart.

He asks God for wisdom, thanks God for his progress, prays for forgiveness and seeks direction.

He needs to believe there is a plan for him, that through faith, he can find a way forward.

[This story was originally published by The Morning Call.]