One state declined a simple tweak to its summer meals program. Thousands of kids paid the price.

The story was originally published in NBC News with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2022 National Fellowship.

This summer, Missouri did not opt into federal child nutrition waivers that for the last two years have given summer meal site operators across the United States license to serve grab-and-go meals.

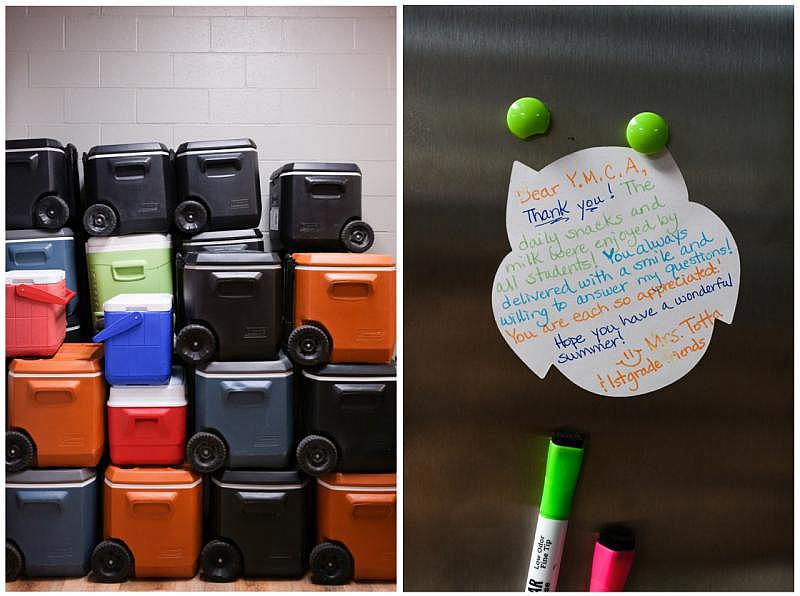

Arin Yoon for NBC News

KIRKSVILLE, Mo. — There was plenty of food in the orange coolers full of free summer meals when a father pulled up, asking for two suppers to bring home to his children. But staff at the meal site in this rural community, where over 60% of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, could not give the man anything.

That’s because Missouri chose not to opt in to a federal waiver that allows parents and kids to pick up meals and take them home, a pandemic-era benefit that vastly expanded access to meals.

Missouri was the only state that did not allow a grab-and-go option for its Summer Food Service Program operators, according to an exclusive NBC News analysis based on responses from all 50 states.

Erin McAlvany's family eat a summer meal site in Kirksville, Mo., on Aug. 16.Arin Yoon for NBC News

The result was a dramatic drop in the number of meals that Missouri kids received: up to 97% fewer than last summer at some sites, community operators across the state told NBC News.

Staff who served meals said they felt like their hands were tied. If meal site operators do not follow the rules of the federally funded program, their organizations do not get reimbursed for the meals they dole out. Yet it was clear, they said, that meals were not reaching everyone who needed them.

Lathen Elschlager is a staff member at the Adair County Family YMCA, which distributed meals to more than 15 sites throughout Kirksville this summer. He was at the site where the father had driven without his children on a recent Wednesday — a mobile home park where kids eat their meals on neatly cut grass. The father was familiar to him: Elschlager said he had seen him come about once a week with his kids before.

Lathen Elschlager. Arin Yoon for NBC News

“It hurts,” Elschlager said. “You know he has kids. But it’s the rules.”

The Summer Food Service Program has been lauded for providing nutrition to kids facing food insecurity across America when school is out. But the program, which has only had a handful of changes to it since its inception in 1968, has limitations.

Prior to the pandemic, meal sites were only allowed in areas where 50% or more of children qualified for free or reduced lunch, which anti-hunger advocates said excluded too many children who were not getting enough food at home.

Rules also limited the times at which meals could be served and required that children eat at the meal sites — two impediments that often did not work with families’ schedules or transportation needs.

In March 2020, Congress gave the U.S. Agriculture Department authority to issue child nutrition waivers. Among the dozens of waivers they have issued since then were ones that loosened meal time requirements and gave parents the ability to pick up meals without their children present. Summer meal staff could bundle food to go, enabling providers to send multiple days’ worth of food home with families so they did not have to return every day at a set time.

Food for meals at the Adair County Family YMCA in Kirksville, Mo. Arin Yoon for NBC News

Those waivers, as well as an even more wide-reaching one that qualified every child for free universal school meals for the past two years, were set to expire in June. As a result, summer meal site operators across the country began this summer requiring children to eat meals on-site.

States got a reprieve with the passage of last-minute legislation at the end of June that gave them the option of extending summer meal waivers. Because school was out and summer was already well underway in many places, not all program operators had the ability to pivot back to grab-and-go meals.

Terri Martin, left, and Shannon Bundridge pack the day's meals at the Adair County Family YMCA in Kirksville, Mo., on Aug. 16. Arin Yoon for NBC News

NBC News contacted officials in all 50 states and found that Missouri was the only one to not provide all of its meal programs with the option to apply for the grab-and-go extended waiver.

A case study in what could happen nationwide

Missouri’s decision not to take advantage of the relaxed rules resulted in fewer children getting meals this summer — in some cases, significantly fewer.

At the Tri-State Family YMCA in Neosho, staff distributed about 9,800 meals a week last summer. That fell to just over 300 a week, a 97% drop, without the waiver extension, CEO Benjamin Coffey said.

Osage Prairie YMCA in Nevada, Missouri, went from serving 2,400 kids a week last summer to about 200 kids a week, a nearly 92% drop, CEO Jeffrey Snyder said. The drop in meals is even steeper, he said, because last summer, families received multiple grab-and-go meals at once.

These numbers likely reflect a lack of access to meals among families, not a lack of need, anti-hunger advocates say, warning that Missouri is a case study in what could happen for the rest of the country next summer.

The No Kid Hungry campaign estimates that before the pandemic, 6 out of 7 kids who may have needed summer meals were not getting them, said Lisa Davis, a senior vice president of the program at Share Our Strength, a nonprofit organization working to end hunger and poverty.

“It is long past time to modernize the summer meals program,” she said.

Many children do not have transportation to summer meal sites or can’t make it during the time windows under the normal USDA rules, she said. Weather can also pose a problem, with sites usually outdoors and sometimes forced to close in storms or excessive heat.

“We know what the policy solutions are that can end child hunger. We’ve tested them during the pandemic,” Davis said. “Yet we’re taking them away and trying to go back to a sense of normal that wasn’t working for many, many families and many, many kids.”

Why Missouri did not opt in

The decision to require eating meals on-site — officially called congregate feeding — was made for practical reasons, according to Sarah Walker, the Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services’ bureau chief of community food and nutrition assistance.

“When we initially opted in to those waivers, we were in the height of the pandemic and Covid-19 operations were taking place in the state,” she said.

In March, Gov. Mike Parson, a Republican, declared an end to the state’s public health crisis, announcing Missouri would be shifting away from an emergency response starting April 1. This played into the summer meals decision, Walker said.

“When the governor declared an endemic, our state became basically normally operated again. So we were able to assume it was safe for people to have congregate-setting meals and things like that,” Walker said in a phone interview in July.

But unlike in past summers, when noncongregate feeding was allowed because of Covid-related health concerns, the extended waivers expanded circumstances permitted for to-go meals. In an email, the USDA said it did “not explicitly define limitation of congregate meal service due to COVID-19.”

Walker said that making sure to-go meals were going to the right place was another concern.

“It’s very difficult to maintain program integrity when the program is not operating under normal circumstances,” she said. “If the children aren’t there, you can’t always guarantee those kids are the ones getting the meals — as opposed to sitting on-site eating, you can assure that it’s the child themselves getting the meal.”

Misti Hollenbeck-Harris, director of membership, wellness and fitness at the Adair County Family YMCA, said her staff did not worry that grab-and-go meals weren’t going to kids.

“Most of the time the children were with the parents, and oftentimes the kids would be getting into the food before they even drove away,” she said.

Misti Hollenbeck-Harris, at the Adair County Family YMCA in Kirksville, Mo. Arin Yoon for NBC News

Kelli Jones, Parson’s communications director, declined to comment on Missouri being the only state to not offer grab-and-go meals.

Nonetheless, there is no doubt that many meals were distributed to kids in Missouri. The state has two agencies in charge of summer meals: the Department of Health and Senior Services, which oversees sites run through nonprofit organizations such as the YMCA and Boys & Girls Clubs, camps and faith-based organizations; and the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, through which schools distributed meals under a different federal program called the Seamless Summer Option.

While community nonprofit groups were bound by pre-pandemic regulations, the education department opted in to waivers to allow for grab-and-go meals and no time restrictions that its 2,227 school sites could apply for, compared to the 1,108 summer meal sites that operated with the restrictions under the health department, per data provided to NBC News by both departments.

In other states, meal sites that could resume grab-and-go meals did — and saw benefits.

At the Baltimore County Public Library, which began offering grab-and-go in late July at 10 branches, the number of meals served only jumped by 25 meals a day, but it made a big difference, CEO Sonia Alcántara-Antoine said.

“Giving families the flexibility of either eating on-site or taking it with them really just helps many of our families, which are frankly just very busy,” she said, adding that many branches exhaust their food supply by the end of each day.

Takeaway meals were a timesaver for people running the sites, too. MetroWest YMCA in Framingham, Massachusetts, started the summer serving one meal at a time five days a week at a park, said Jeanne Sherlock, chief operating officer. Last summer, she said, staff went to the park only three days a week and could give people multiple days’ worth of food each time they served.

“We were spending twice the time to distribute a third of the meals” before resuming bundling multiple meals together in to-go packs this summer, she said.

In Kirksville, Missouri, YMCA staff went from distributing more than 11,000 meals in July 2021 to 5,000 this July. They made the most of not having a to-go option — playing checkers, Connect 4 and bean bag toss or reading with kids who were eating.

Erin McAlvany at a meal site in Kirksville, Mo., on Aug. 16. Arin Yoon for NBC News

Erin McAlvany and her family live about five blocks from two parks that host meal sites. She brought the kids by about once a week.

Last summer, having grab-and-go “was a dream,” she said. “We could eat and play if the weather was good, but we had the convenience to leave.”

Sites with no place to play were especially difficult with no grab-and-go option. With no playground and sometimes no shade, meal sites at mobile home parks, for example, could be challenging, staff said.

“Kids don’t want to just grab them and sit down like 20 feet from their house and sit. They want to go inside and eat at their house,” Elschlager said.

Emily Gillaspy, a Kirksville mom to seven children including three foster children, said she used to pick up grab-and-go meals last summer for her kids, but could not come for meals this year.

“One meal can drastically change my food budget, so not having grab-and-go, it does make a dent,” she said, adding that a local food bank has helped.

Erin McAlvany's family receives meals at a meal site in Kirksville, Mo. Arin Yoon for NBC News

McAlvany's family plays at a meal site in Kirksville, Mo. Arin Yoon for NBC News

A call for action before next summer

There are congressional attempts to help feed more kids. A child nutrition reauthorization bill advanced by a House committee in July proposes making permanent changes to a range of federal child nutrition programs.

While the Healthy Meals, Healthy Kids Act does not include a provision for making grab-and-go meals permanent, it contains other provisions to expand summer meals, including lowering the area eligibility requirement so that communities could participate in free summer meals if 40% of children, rather than 50%, qualified for free and reduced lunch. It would also allow sites to serve up to three meals a day as opposed to capping their maximum at two.

Coolers and a sign at the Adair County Family YMCA in Kirksville, Mo., this month. Arin Yoon for NBC News

But there has been no movement on the bill, with no version introduced in the Senate.

Sen. John Boozman, R-Ark., a sponsor of the Keep Kids Fed Act and ranking member of the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee, said he strongly backs grab-and-go meals and that he felt the pandemic proved there should be support for them going forward.

“Noncongregate feeding makes all the sense in the world,” he said.

He said he thought a standalone bill would have a greater chance of getting grab-and-go meals to be made permanent and said the Keep Kids Fed Act, the legislation that extended the federal waivers in June, was successful in getting passed quickly because of its narrow focus.

If a future bill were specifically focused on non-congregate feeding, he added, “I think we would have a much better chance of actually getting legislation passed.”

Boozman did not provide a timeline other than to say he felt there was a “good chance” it could get done in the coming year.

Sen. Debbie Stabenow, D-Mich., another sponsor of the Keep Kids Fed Act and chairwoman of the Senate Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry Committee, did not say whether she would back a separate bill, but said “I strongly support extending essential summer meals for children and look forward to including this funding as we work to reauthorize our child nutrition programs.”

Davis of No Kid Hungry urged Congress to make feeding kids a priority, arguing its return on investment shows up in health care, education and other areas of children’s lives.

She called the pre-pandemic format of the Summer Food Service Program insufficient.

Children follow as Christina Pinkerton and Shannon Bundridge take food for the summer meals program to the picnic area in Kirksville, Mo., on Aug. 16. Arin Yoon for NBC News

“It is not OK that you have a program that is supposed to feed kids in the summer and it is only reaching 1 out of every 7 kids,” she said. “That’s just not good enough.