The opioid epidemic isn't hitting LA as hard as the rest of the country. Ethnic diversity might explain why

This story was produced as a project for USC Annenberg's Center for Health Journalism California Fellowship.

Other stories in the series include:

Is pot the answer to keeping seniors in pain off opioids and other prescription drugs?

ales shows an herbal remedy she uses to treat back and knee pain.

By Michelle Faust

America’s opioid epidemic has devastated many communities. More than 42,000 deaths were attributed to the painkillers in 2016, in both prescription and illegal forms.

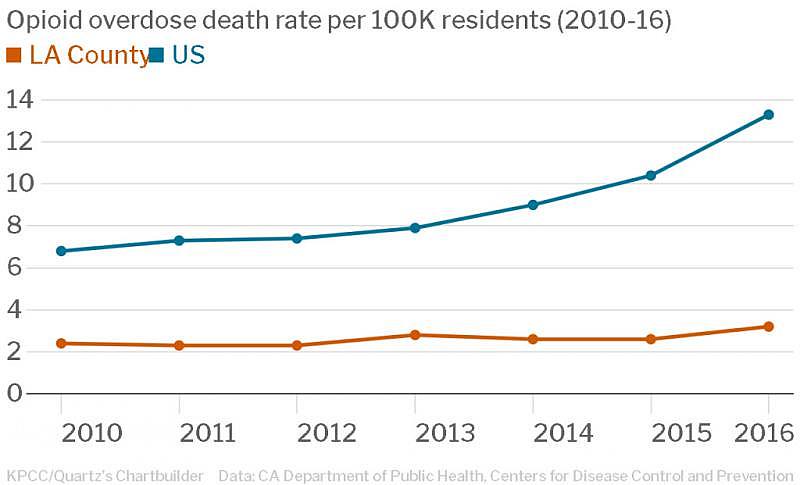

Los Angeles County has not gone unscathed. But the rate of deadly overdoses here is much lower than the national rate. In 2016, the county had a rate of opioid overdose deaths of 3.2 per 100,000 people. The national rate was 13.3 per 100,000 people.

Why the steep disparity?

Some experts say the region’s racial and ethnic diversity is likely a factor. Latinos and Asian-Americans are both less likely to ask for or be offered opioids by doctors.

"When you have a situation where certain cultural groups are prescribed less medications, and they also use less medications, you have a situation where cultural diversity likely is protective in terms of the opioid epidemic," said Dr. Gary Tsai, medical director of the L.A. County Department of Public Health's substance abuse prevention and control program.

It’s not that Americans have more pain than the rest of the world. Tsai says, it’s that they respond differently to it.

"Without a doubt,” he said, "the opioid epidemic is a cultural problem."

CARMEN'S STORY

When it comes to dealing with chronic pain in her back and knees, Carmen Morales has felt the differences between her Peruvian heritage and American upbringing.

The bubbly 31-year-old L.A. resident grew up watching her parents use traditional medicines.

"When I get sick, when I have a cough, I make my dad’s little remedy," said Morales. "And hey! I’m up and going the next day. But I am of a different generation where we do medicate."

In her early 20s, Morales injured her back severely in a collision with a drunk driver. For four years, she used opioids, including Vicodin, on and off to treat the pain.

Morales eventually stopped taking the drugs out of fear of their long-term effects on her health. But the pain persisted and ignoring it wasn't a solution.

"So my coworker said, ‘Listen! Why don’t you go meet with my mom’s friend who is a sobadora and has been helping people for a long time?'" Morales said.

Carmen Morales shows some of the essential oils and herbal remedies she uses.

Sobadores are traditional Latin American healers who specialize in therapies that include massage and herbal remedies.

Morales was skeptical, but her intense back and knee pain had her hobbling around. She figured it was a worth a try.

"I reluctantly went, because I’m a science person," she said. "I’m not really a believer."

But Morales changed her tune after her first visit.

"She pulled my leg and it was like this noise. It was complete, immediate release. I was like, 'Okay! See you next Tuesday!'"

Morales saw the sobadora regularly for a time and still has a lot of the herbal remedies she gave her.

They are just a few of several alternative methods she uses to treat her pain, including acupuncture, meditation and exercise – and some studies have shown those activities can help manage chronic pain.

"PAIN EXISTS IN A SOCIAL ... AND CULTURAL CONTEXT"

Morales' story resonates with Dr. Adam Hirsh, a psychologist who has conducted numerous studies on pain and how it intersects with culture.

"We found some evidence suggesting that Hispanic Americans are more likely to use alternative sources of care for chronic pain than are non-Hispanic whites," said Hirsh, an associate professor of psychology at Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis.

"Pain exists in a social context and it exists in a cultural context," he said.

Research supports the assertion that people from different cultures handle chronic pain in different ways, said Hirsh, adding that his work has found that Latinos are more likely to show stoicism when facing chronic pain.

"Those cultural differences certainly matter whenever we’re trying to get a sense of differences in pain care across these racial and ethnic groups," he said.

L.A. County Public Health's Tsai pointed to research that shows Latinos and Asian-Americans are more likely to shy away from pills.

DISPARITIES IN CARE

Carmen Morales rubs cream on her knees to ease the pain.

There may also be more troubling reasons.

Experts point to research that has found doctors are less likely to prescribe pain medication to Latinos and African-Americans.

For one thing, when doctors aren’t of the same background as their patients, cultural misunderstandings can arise regarding how the patients are experiencing their pain, said Hirsh.

"Oftentimes, especially for Latinos, we’re also talking about language barriers, " said Hirsh. "I think that just amplifies the challenges for racial and ethnic minority groups with chronic pain to get appropriate care."

People can also be denied pain medication because of racial and ethnic discrimination.

Tsai says it’s not good if discrimination or cultural miscommunication in the doctor’s office is preventing patients from getting help that they need.

At the same time, he believes society at large can learn something from the reluctance of Latinos and other groups to turn to pills to deal with chronic pain.

[This story was originally published by KPCC.]

[Photos by Michelle Faust / KPCC.]