Opioid Orphans: Grandparents Struggle to Raise Children Left Behind

The story was originally published by the MindSite News with support from our 2024 National Fellowship.

Every year, Libby Walker, shown in the foreground, attends a December vigil in downtown Huntsville at the Angel Tree, which honors the memory of loved ones lost to drug overdose. She attended last December’s with her granddaughters, including Janiya, right.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Despite billions of dollars raised from opioid settlements, grandparents raising grandchildren get little support

The past five years has seen a tragic rise in the number of children experiencing the death of a parent – from COVID, gun violence and opioid overdoses. The story of the children they left behind has gotten far too little attention. In this story, part 4 of our Forgotten Children series, we look at the large number of grandparents who have stepped up to raise their grandchildren.

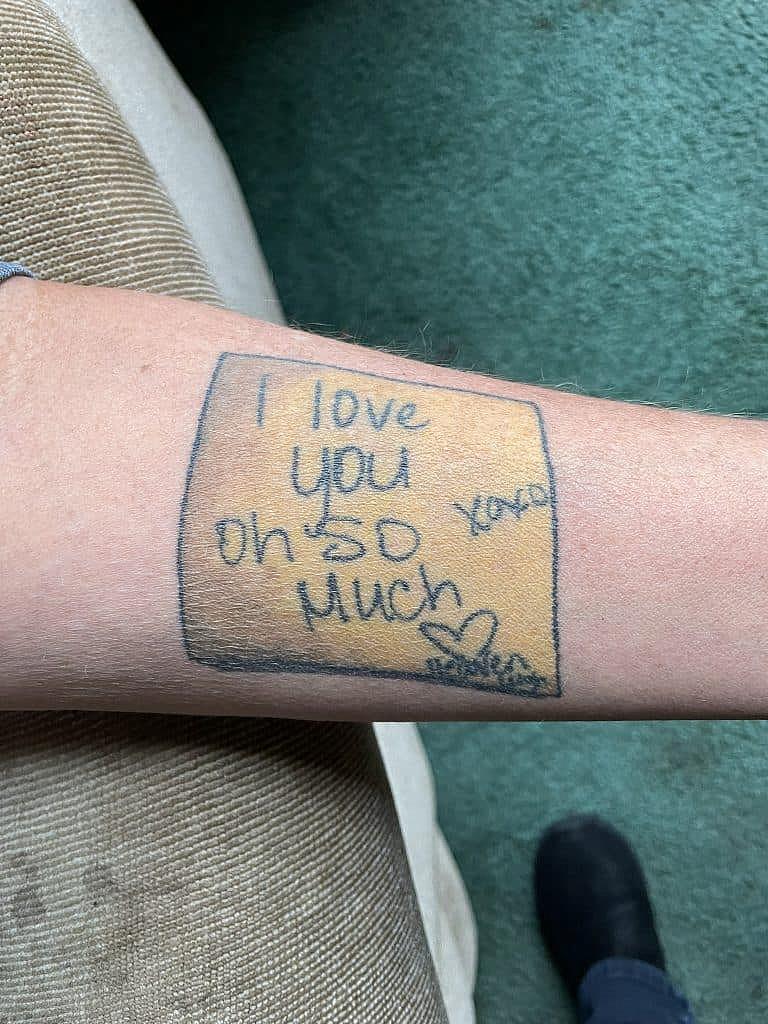

Libby Walker pushes up her sleeve and reveals the tattoo on her left forearm, a three-inch square with a tint of yellow. “I love you Oh SO Much,” it says in big, rounded handwriting. There’s a heart beneath the words and XOXO to the side. For the rest of her life, Walker will wear the last message her daughter, Heaven Leigh, left her on a Post-it note before she died of a fentanyl overdose on August 1, 2020, at the age of 30.

Libby Walker made a tattoo of the last message her daughter sent her.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

The tattoo is a testament to the enduring bond of Walker’s love for Heaven – and for Heaven’s three daughters, whom she is raising. She gave up her job as a service adviser at a Toyota dealership and instead drives a school bus – and makes occasional DoorDash deliveries – so she can be available for the teenagers. That means money is tight: her income and the girls’ Social Security payments combined are just $100 a month above the threshold that would qualify for food stamps.

The last message from Libby Walker’s daughter, Heaven Leigh, which she left on a Post-It note for her mom before her death from an overdose.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

They live in a double-wide trailer in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains, in a community outside Huntsville, Alabama, that is about six miles south of the Tennessee line. The double-wide is big enough for each girl to have her own room, with a full-sized bed. Walker also finds a way to accommodate her son and his young children for a few days each week and even, on occasion, Jeromy Ramsey, Heaven’s former partner and father of the girls.

Just inside the front door hangs a plaque with inspirational sayings, including “Follow your heart/It is the only compass you need.” The words underscore Walker’s resolve to do the best she can with the hand she’s been dealt.

Walker, 54, has struggled in the years after Heaven’s death, not just financially but with her own grief and her granddaughters’ silence about their loss. “I’m here to talk, if they ever need to,” she said of the girls, ages 13 to 16. “We remember their mama every day. Every day we talk about something.” They flip through photos on Heaven’s cellphone, a cascade of selfies showing Heaven’s silly, joyous and loving personality. Every year on Heaven’s birthday, Walker bakes a cake and they celebrate together. But when Walker tries to talk to the girls about their feelings – sadness, anger, loss – they clam up.

She is looking for a therapist for one of the girls, but Walker learned the hard way that grandparents typically do not get any special assistance when they step up to care for the children left behind after parents die of a drug overdose. “There needs to be a better system” for grandfamilies, says Walker. “They should get the same benefits foster children get, and they don’t.”

Appalachia ‘losing a generation of parents’

Walker felt alone when she began navigating a second round of parenting, but she is not. Drug overdoses strike in the prime of life – the nation’s highest overdose death rate is among people 35 to 44. In 2020, amid the pandemic shutdown and threat of COVID, opioid overdose deaths continued to surge. One in five children grieving the death of a parent had lost them to a drug overdose, according to estimates from the JAG Institute, a research initiative of Judi’s House, a comprehensive child and family grief center in suburban Denver.

Researchers have tried to put a number on the toll of the opioid epidemic on the children left behind. In the decade from 2011 to 2021, an estimated 321,566 children lost a parent to drug overdose, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, which collaborated on the research with other federal health agencies. Parental deaths from drug overdose accelerated during the pandemic, rising by almost 50 percent from 2019 to 2021.

Across Appalachia, in particular, overdose deaths have shattered the cocoon of childhood. In West Virginia, for example, 13.7% of children – almost one in seven – will grieve the death of a parent by the time they turn 18, according to the JAG Institute. That’s the highest rate in the nation. “In Appalachia…the number of overdose deaths is so great that it’s like essentially losing a generation of parents,” said Erin Winstanley, a behavioral health researcher at the University of Pittsburgh, who holds an adjunct position at West Virginia University.

Heaven Leigh Walker, a factory worker and mother of three small girls, became addicted to opioids after she was prescribed them for pain from a knee shattered in a fall.

Photo courtesy of Libby Walker

With the nickname “Rocket City,” Huntsville, Alabama, seems shielded from the despair felt in impoverished rural outposts. It is home to NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center, which powered American astronauts to the moon, helped build the International Space Station and enables exploration of the solar system. In May 2023, US News & World Report named Huntsville the second-best place to live in the U.S. But it is far from immune from the opioid epidemic. Even as fatal drug overdoses declined nationally from 2022 to 2023, they continued to rise in Alabama and nine other states.

Opioid painkillers’ slippery slope

Heaven’s descent into addiction is a very personal tragedy, but also hauntingly familiar – a scenario that has unfolded countless times, in different variations, since Purdue Pharma and other pharmaceutical companies began aggressively marketing extended-release oxycodone in 1996. Walker recounted the story:

In 2011, Heaven was a harried young mom of three small children. She was wearing flip-flops and holding the handle of a baby carrier as she hurried across a parking lot to take her two-month-old to a doctor’s appointment. She stepped on a slippery patch and fell hard on her knee, shattering it.

An orthopedic surgeon patched it together, but the pain persisted. Opioid medication helped her function, both in a factory job across the state line in Tennessee and as a mom. But over time, she became hooked. Then, like so many others caught in the web of the opioid epidemic, the prescriptions ended and she discovered that heroin was effective and cheaper. and later that fentanyl was more effective and cheaper still.

In November 2016, Heaven was on the way to work in Fayetteville, Tennessee, when she was stopped by the police for an expired tag – and was cited for not having a valid driver’s license. She was ordered to pay $50 and court costs, but the penalties began to mount when she missed a court date a few months later.

In Appalachia…the number of overdose deaths is so great that it’s like essentially losing a generation of parents.

Erin Winstanley, a behavioral health researcher at the University of Pittsburgh

As Heaven struggled to keep her life together, Walker recalled, she remained devoted to being a hands-on parent and was close to her daughters. Then, a couple of years before she died, an anonymous person reported her to the Alabama Department of Human Resources, and she failed a drug test. She began outpatient rehab and started taking Suboxone, an opioid blocker. Walker cared for the girls, and Heaven rented a trailer next door. For a time, she was doing well, still working at the factory, and regained custody.

In 2019, Walker recalls, Heaven was shaken by the death of two people very close to her – her godmother (the mother of a close family friend) and grandfather (Walker’s father). Walker vividly remembers Heaven’s last spiral, a series of events that she dissects over and over in her mind as if she might be able to unravel it, or at least find a measure of peace.

When Heaven was charged with failing to appear for a court date, she spent a night in jail and lost two days of work, without giving notice, which led to her firing. She was evicted from her trailer. Then she received an 11/29 sentence – 11 months and 29 days for a misdemeanor offense – which was suspended as long as she paid the fees and kept up with her supervised probation, which also involved fees.

When she missed another court date and a probation officer said she had violated her probation, a judge sentenced her to 200 days in the Lincoln County jail. She reported for jail on December 20, 2019 – and after being booked in, experienced an overdose and ended up in the hospital. She recovered and remained in jail until July 6, 2020.

“It was just a ripple effect of everything,” said Walker, and it combined with the deaths of Heaven’s godmother and grandfather. “That pretty much sent her over the edge.”

Libby Walker looks at photos of her daughter, Heaven Leigh, in happy times.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

When Heaven got out of jail, she was sober – but emotionally shaky. Walker suspected she was slipping back into the habit that numbed all the painful feelings. At 5:30 a.m. on August 1, 2020 – 26 days after her release – Heaven typed her last Facebook post while her mom lay sound asleep in a nearby bedroom. At about 7:20 a.m., Heaven’s boyfriend knocked on Walker’s door, opened it, and said: “Something’s wrong with Heaven.”

Walker still can see the surreal scene of Heaven being loaded into an ambulance, a portable ventilator pumping oxygen into her lungs. She never woke up. Walker figures Heaven had lost her tolerance so that an amount of fentanyl she might have previously taken was now fatal. Studies have documented the increased risk of overdose death after incarceration, particularly in the first weeks after release.

Walker brought the children to their grandfather’s Tennessee home, where she had asked family members to gather – aunts, uncles, cousins. Together, they broke the news of Heaven’s death.

When she recounts the story, Walker seems to be looking for the turning point that could have led to a different path. “I always beat myself up about it. I should have done something. I should have done something,” she said, her voice breaking. But in the end, she added, she could not have changed anything: “It’s God’s plan. You can’t stop it.”

Grandparents As Parents to the rescue

When Heaven was wrestling with her opioid use disorder, Walker knew of many other families locked in a similar struggle. She just didn’t know of any way to get help in supporting the children. Then just over a year ago, Walker met another grandmother raising her grandkids after a grown child’s death from a drug overdose, and she learned of a man named Keith Lowhorne.

Lowhorne, a former local TV news director, and his wife Edie began caring for their grandson Kyren, now 11, when he was born with neonatal abstinence syndrome – suffering from withdrawal from the drugs his mother had been taking. When Kyren’s sister Harper, now 8, was born, also impacted by prenatal drug exposure, the Lowhornes were able to adopt both children. Their father had died of an overdose and their mother – Edie’s daughter from a prior marriage – had her parental rights terminated by a judge. Keith and Edie are the only parents Kyren and Harper have known.

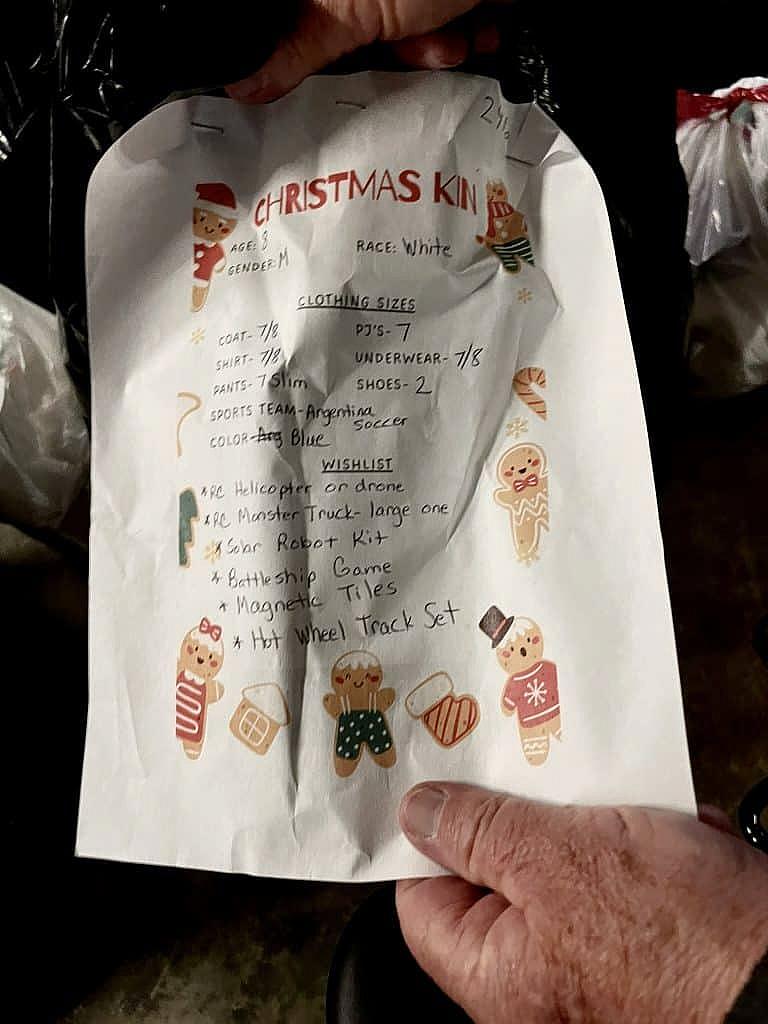

A child’s wishlist for Christmas for Kin, which serves grandfamilies.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

While this second round of parenting upended their retirement – they canceled European travel plans – they always knew they were more fortunate than many grandparents in their situation, and they were always involved in charitable work. During the pandemic, word got around that Lowhorne was able to help people with basic needs, and the calls multiplied. He soon formalized his efforts, creating Grandparents as Parents, or GAP, as a charitable organization, and he now gives away donated food every week from the front yard of his home in tiny New Market, Alabama, and arranges GAP support meetings at a local church.

At 68, Lowhorne still has a boyish look, passion-fueled energy – and an impressive contact list, which he puts to good use. For their annual Christmas for Kin event, the Lowhornes find sponsors to buy items on the Christmas wish lists of children being raised by grandparents. Last Christmas, 298 children received gifts through the program.

Yet Lowhorne wants to go beyond food staples and Christmas presents. So far, opioid manufacturers, marketers, distributors, and retailers have agreed to pay about $50 billion to state and local governments in opioid settlements, and Lowhorne thinks at least a drop of that should go to help grandparents struggling to care for their grandkids.

Currently, most of those funds go towards prevention and treatment of substance use disorder, including naloxone training programs and kits to reverse opioid overdoses. States allocated just 1.4% of the money to support maternal care programs for people with opioid addiction in 2022 and 2023 and .38% to help babies with neonatal abstinence syndrome in those years, according to a KFF Health News investigation.

That doesn’t address the needs of the broader group of children left behind after drug overdose deaths. In Alabama, the leading reason children entered foster care in fiscal year 2022 was parental substance use – encompassing 44% of all new cases, according to a December 2023 report by the Alabama Opioid Overdose and Addiction Council.

Yet grandfamilies and kinship care are rarely part of the conversation about how to spend settlement funds. Lowhorne aims to change that. “There is no one, absolutely no one, that should be more important than the grandparents that are raising these grandchildren as their own,” he said.

Grants for grandparents raising grandchildren

To Lowhorne’s point, there’s plenty of data showing that the opioid crisis pushed grandparents into a new cycle of parenting, upending retirement plans and straining their financial and physical capacity. States with the highest opioid prescribing rates also had the highest proportion of people raising grandchildren, according to a 2019 U.S. Census study.

Former TV news director Keith Longren created Grandparents As Parents and recruits donations for holiday toys – including bicycles – for kids being raised by grandparents.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Alabama ranks second-highest in opioid dispensing in the country– just behind Arkansas – with a rate twice the national average. The state has 59,025 grandparents raising grandchildren, according to Generations United, an advocacy organization that promotes intergenerational collaboration. Nationally, an estimated 2.5 million children are in the care of grandparents, or more than 3% of all children.

States across the South rank high in the U.S. Census Bureau report for grandparents raising grandchildren: Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Alabama, and West Virginia were at the top in 2023, according to the Kids Count Data Center of The Annie E. Casey Foundation. While grandparents can apply to become kinship foster parents and receive state support, that puts the children under the supervision of the state – a scenario many grandparents prefer to avoid.

Lowhorne has been advocating for direct aid to help caregiving grandparents pay for necessities for their grandchildren – and he’s finally seeing some money trickle to them. In a pilot program, three Area Agencies on Aging – encompassing 15 counties in southeast, southwest, and northeast Alabama – will each distribute about $93,000 in one-time grants of $500 per child to cover necessities such as food and clothes. The money comes from Alabama opioid settlement funds, which will total more than $760 million – not including a future Purdue Pharma settlement – to be accrued over 10 years and dispersed by state and local governments.

Getting those grandfamily grants in place has taken about a year of rule-making and contract-signing with state agencies, and the funds can be used “for any cost associated with raising a child or helping the child live a positive life,” according to the Department of Mental Health. The first payments began in late 2024.

Grandparents have felt “a sense of utter frustration that they were being left behind and feeling not heard. So it gives them hope to see that in one state, raising awareness had an impact.”

Jaia Peterson Lent on why grandfamily grants are needed

Similar programs operate in Ohio, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and other states. In February, West Virginia grandmother Elizabeth Mateer, raising a grandson due to her daughter’s substance use disorder, testified at a U.S. Senate hearing on aging adults and the opioid epidemic. She called grandparents raising grandchildren “one of the least recognized populations impacted in the opioid crisis.”

Those grandparents have felt “a sense of utter frustration that they were being left behind and feeling not heard,” said Jaia Peterson Lent, deputy executive director of Generations United, which advocates for grandfamilies. “So it gives them hope to see that in one state raising awareness had an impact.”

Lowhorne hopes this is just a beginning; he’s working on a grandfamily wish list. He wants a “one-stop shop” – a single location where grandparents raising grandchildren can get help with their own senior services as well as support for the children. Since senior housing generally excludes children, he also dreams of establishing Alabama’s first grandfamily “village” in Huntsville – a place designed for grandparents raising grandchildren.

“It’s about trying to help grandparents like us,” says Lowhorne. “We see grandparents who are suffering all the time.”

At the Tinsel Trail in downtown Huntsville, the “Angel Tree” sponsored by Not One More Alabama honors the memory of people who died of an

overdose.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Complicated grief

Overdose deaths trigger a complicated kind of grief, especially for the children left behind. At the Resilience After Complex Trauma (ReACT) clinic at West Virginia University in Morgantown, psychologist and trauma specialist Maria Khan sees children who have lived for years with parents going through cycles of sobriety and relapse, periods of neglect and poverty, feelings of abandonment and self-blame for not being able to stop the parent from using or saving them from an overdose.

Some families, including grandfamilies, travel for hours to her clinic, but like many similar programs around the country, her clinic is under-resourced. “I’m one of the very few psychologists providing trauma-focused treatment in the state,” said Khan. “The waitlist is quite long but our aspirations are to be as wide reaching as possible.”

If we want to stop intergenerational substance use disorders, then we need to address the mental health needs of these kids, because we are predisposing a new generation to trauma.

Researcher erin winstanley

Erin Winstanley, a researcher who studies substance use and mental health disorders, began examining the impact of overdose deaths on children during the second wave of the opioid epidemic starting around 2010, when heroin use escalated.

She found that while children may witness their parents experiencing an overdose – fatal or non-fatal – there is little research about the psychological or behavioral outcomes they encounter. Similarly, while it is well-known that many grandparents have stepped up to raise grandchildren in families impacted by addiction and overdose, research is lacking on how this impacts grandfamilies, Winstanley said.

“If we want to stop intergenerational substance use disorders and this exposure to trauma, then we need to address the mental health needs of these kids, because we are predisposing a new generation to trauma,” Winstanley told MindSite News. Living in a home where a family member has a substance use disorder is considered an adverse childhood experience, and can lead to future drug and alcohol use, emotional problems and health and mental health disorders. “Protecting these kids is critically important,” Winstanley said.

Libby Walker’s granddaughter Janiya, 15, shows her “angel wings” pendant that holds a photo of her and her mother, Heaven Leigh, at a gathering for Not One More Alabama, an organization that supports families struggling with overdose disorder.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Hugs, tears, and facing the reality of death

The white clapboard house across the street from the campus of Huntsville Hospital looks like it could be the studio set of a 1950s-era sitcom. It has a white picket fence, a hedge under the front window and a teal-colored window box with potted flowers.

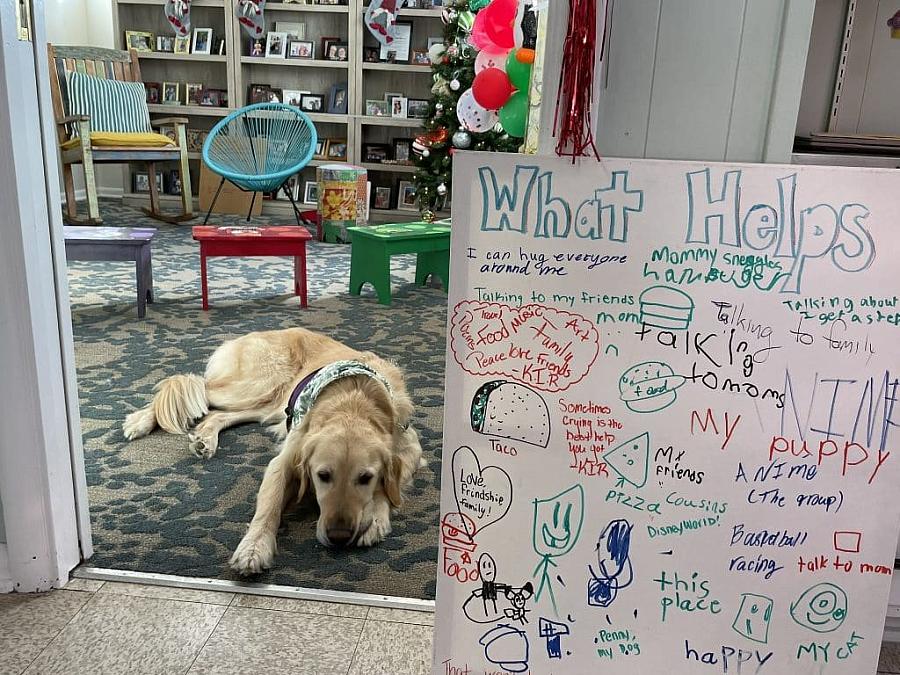

Inside, The Caring House is just as cozy, with snacks and hot chocolate in the kitchen, art supplies and toys galore, a huge stuffed Teddy bear, and a floppy-eared golden retriever named Paxton who loves hugs. The Caring House is patterned after The Dougy Center, which opened in Portland, Oregon, in 1982 and became a global model for a peer-support-based grief center for children and their families.

Trauma and grief therapist Jill Falling and two certified child life specialists coordinate groups for children and teenagers, separate groups for surviving parents and other caregivers, and one-on-one sessions for those who need individual care. They see children whose parents died suddenly in a car accident or after a prolonged sickness such as cancer.

But some deaths, such as from drug overdose or suicide, carry the extra burden of stigma, and the surviving parent or caregiver may feel conflicted about how much to tell the children.

It can be especially difficult for grandparents to start the conversation with grandchildren, said Falling. “They’re trying to manage their own grief, and sometimes they don’t have the capacity to work with the child’s grief,” she said. “That’s a complicated dynamic.”

At The Caring House, children can act out scenarios in the playroom. They might place a note to their deceased parent in a bottle filled with colored sand. On a board labeled “What Helps,” kids have written: “I can hug everyone around me…Love, friendship, family…Sometimes crying is the best help you got…” And someone added: “this place.”

Paxton the therapy dog lies next to a poster board where children have written about what helps them cope with their grief. He’s one source of comfort.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill.

A vigil for Heaven

Libby Walker at a December vigil in downtown Huntsville at the Angel Tree, which honors the memory of loved ones lost to drug overdose.

Photo: Michele Cohen Marill

Lights twinkle in the winter night from Christmas trees that wrap around Big Spring International Park in downtown Huntsville. Known as the annual Tinsel Trail, families come every evening between Thanksgiving and New Year’s Day to admire the creative and festive decorations of more than 400 trees.

But on a night in early December, a somber crowd huddled around the tallest tree. Every year, Not One More Alabama, an organization that supports families of people struggling with substance use disorder, decorates a large Angel Tree, with a halo on top and photos of loved ones who have died of a drug overdose. Every year, the collection of photos grows larger. Every year, they are mostly young adults.

“This candle represents your loved one,” said Rev. Bill Crosby, a pastor at First United Methodist Church of Huntsville, in a soothing talk that reassured the huddled crowd that they are not alone in their grief. “In the midst of the darkness, hold the light, knowing there’s hope.”

Libby Walker stood at the vigil with her granddaughters, their father, and Walker’s best friend. She cupped her hand around the flame of her candle as she listened to the speakers, who offered comfort, remembrance, and solidarity. Sharp wind gusts blew the branches of an overhanging willow oak tree, and its thin, brown leaves fell like tears.

Walker and her granddaughters come to this vigil every year. She sometimes submits different photos of Heaven; her youthful smile is frozen in time. “I just like her to be remembered,” said Walker as she walked back to her car after the vigil. “Don’t want her to ever be forgotten.”