After the First Cry: Chinese Mothers Left to Navigate the Long March Alone

This article was originally published in World Journal with support from our support from our 2025 Impact Fund for Reporting on Health Equity and Health Systems.

Many immigrant mothers face exhaustion that runs deeper than sleepless nights — the loneliness of raising children far from family, amid high costs, scarce support, and quiet emotional strain.

(Courtesy of Ada Teng)

By the time Lily Wang reached Los Angeles in 2023, she was seven months pregnant and exhausted.

She and her husband had traveled from China and crossed the rugged mountain paths along the Mexico–U.S. border at midnight, believing it was the hardest moment of their lives. They were asylum seekers with no family nearby and no clear idea of what lay ahead.

More difficulties lay ahead in the months after childbirth. Their newborn woke every two hours, and Wang, struggling to produce milk, searched online forums in Mandarin for help. “I felt like I was failing,” she recalled. Her body ached, her eyes burned from sleepless nights, and the apartment walls closed in.

Seven months pregnant, Lily Wang crossed the rugged mountains along the U.S.–Mexico border with her husband to seek asylum. Now, caring for two young children, she often feels she can hardly catch her breath.

(Photo by Ziwei Liu)

Two years later, she found herself unexpectedly pregnant with a second child. When the baby was born, survival became a daily routine. The infant needed constant soothing while her toddler demanded attention. “I often felt torn in two,” Wang said.

Her husband, a nighttime truck driver, tried to help. To keep their older daughter close, he sometimes made up a small bed for her in the truck’s passenger seat while he worked. Between overnight shifts and daytime childcare, he rarely slept, and over time, the lack of rest began to affect his memory — he would sometimes forget small things he had done earlier in the day.

For Wang and many immigrant mothers like her, the exhaustion was not just physical — it was the loneliness of raising children far from family, often with partners working long hours or away from home. Across Southern California, these families face obstacles that stretch far beyond the nursery: the soaring cost of care, the absence of reliable support, and a quiet emotional strain.

The Burden They Carry

In Southern California, where wages lag behind the cost of living, even the most basic of childcare can feel like a luxury. The numbers alone are daunting: daycare centers in Los Angeles charge between $1,200 and $2,000 per month for infants and toddlers, according to the Illumine Childcare Cost Report.

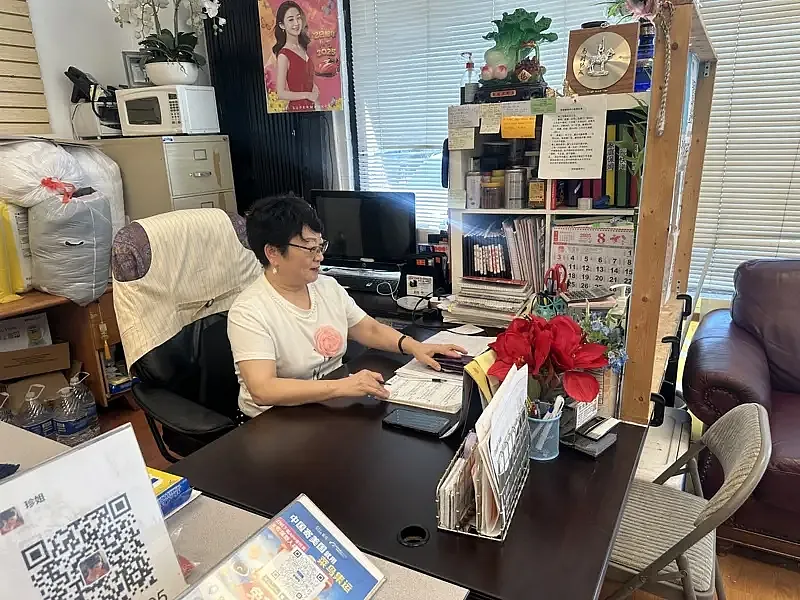

Hiring private help is even steeper. Jane Zhang, who has run a Chinese nanny agency in Monterey Park for more than a decade, said regular nannies typically charge $200 to $250 a day, depending on experience and duties. Postpartum caregivers known as yue sao (月嫂) — comparable to doulas in Chinese culture — cost even more, about $250 to $400 a day, since many live with the family during the crucial first month after birth, tending to both mother and baby through sleepless nights. “Most families we work with usually pay over $5,000 every month,” Zhang said. “It’s not easy to afford for anyone.”

To put into comparison, Los Angeles County’s median household income in 2024 was $86,587, roughly $7,215 a month.

Jane Zhang, who has run a Chinese nanny agency in Monterey Park for more than a decade, says most families she works with spend over $5,000 a month on childcare — “a cost that’s hard for anyone to afford.”

(Photo by Ziwei Liu)

For Lily Wang, those figures translated into hard choices. As a full-time mother of two kids, her family relied on her husband's single paycheck. Hoping for a brief rest, she once enrolled her older daughter in daycare — but the $1,000-plus tuition quickly felt like a burden. Within weeks, her daughter began catching frequent colds and coughs that spread through the family, leaving her husband too sick to work. “It just wasn’t worth it,” Wang said, eventually pulling her out.

In Alice Lin’s case, two salaries rarely bring relief. Lin and her husband both work full-time in media and administrative jobs in Los Angeles County, earning about $6,800 a month together. After mortgage payments, car loans, and insurance, almost nothing remains. Their son’s birth in 2022 brought joy — and financial squeeze. They couldn’t afford a nanny, but neither was willing to give up their career to care for the child.

At first, their parents from China came to help. But tourist visas allowed only six-month stays, forcing a draining cycle of arrivals and departures. “Every time they left, we started over,” Lin said. When their toddler finally entered daycare, the $1,300 monthly tuition erased what little buffer they had. Lin once thought about doing part time gigs to increase income, but, “Between work and childcare, there’s just no space left for anything else,” she said.

Lin had also researched government support programs but found herself shut out of nearly all. “Most of the benefits are interconnected,” she said. “If you qualify for one, you usually qualify for others. But if you miss one threshold, everything disappears.”

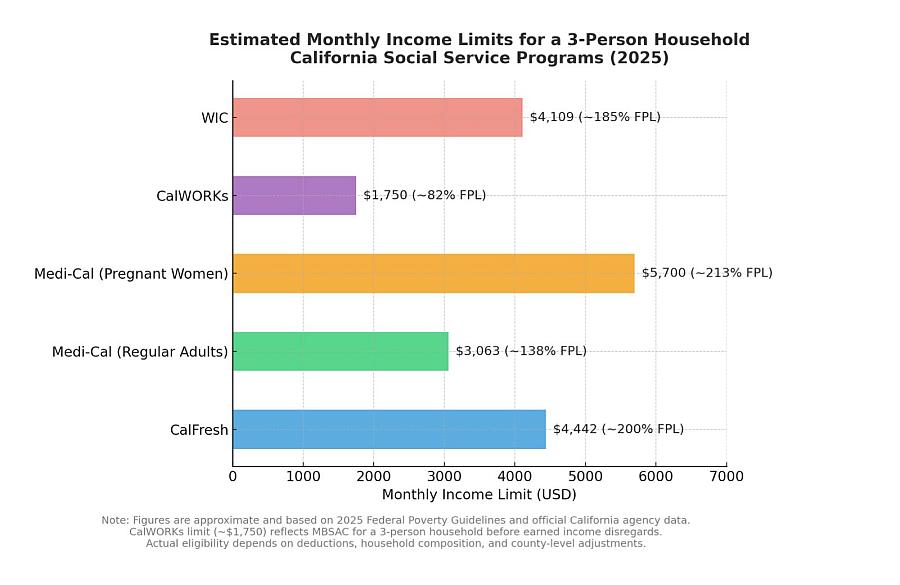

For a family of three, most public assistance programs in California require a monthly household income below $6,000.

(Data sourced online as of September 2025; graphic by Ziwei Liu)

For a family of three, most California programs — such as WIC, the federal nutrition program for women and children, or Medi-Cal Access, the state insurance plan for pregnant women — set income limits below $6,000 a month. Some families earning slightly above the income limit can occasionally obtain subsidies, but the margin for eligibility is narrow, leaving most without support.

The result is a widening middle band of parents like Lin: neither poor nor secure, too “comfortable” for aid yet too stretched to thrive.

Beyond the numbers lies another kind of cost — the fatigue of doing everything alone. For many mothers, the absence of affordable, reliable help means caretaking alone.

Fen Chen, a mother of two living in West Covina, sits at the far edge of that exhaustion. Her husband, a long-haul truck driver, is home only a few days each month. “He wouldn’t even pick up a bottle if it fell,” she sighed.

Fen Chen has largely raised her two children on her own. Her husband works away from home most of the year, and when relatives came to help, constant disagreements left her to manage everything herself.

(Courtesy of Fen Chen)

Grandparents, once the traditional safety net in Chinese families, no longer guarantee relief. When Chen’s in-laws came to help after her first child was born, differences in parenting styles and daily routines quickly turned into conflict. Arguments over feeding, sleep, and household chores left her vowing never again. “Most mothers I know who rely on grandparents end up with problems,” she said. “But it’s the only option left when you can’t afford private help.”

When the house finally falls silent, mothers like Chen often find their minds still racing — too tired to rest, yet unable to stop. The burden doesn’t end with the day’s chores and help feels out of reach.

When Stigma Meets Silence

For many Chinese mothers, that quiet weight rarely finds an outlet. Between stigma, language barriers, and limited options, reaching out — let alone trying to find culturally competent help — often feels overwhelming.

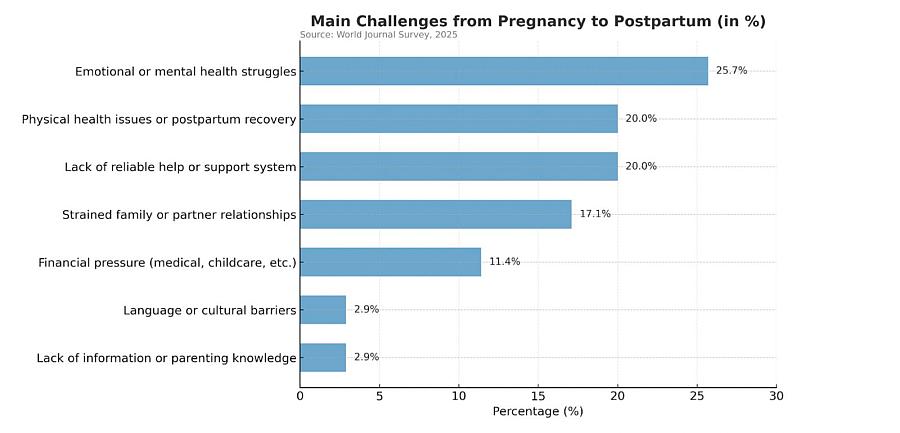

In a World Journal survey of Chinese immigrant mothers in Southern California about their experiences with health care before, during, and after childbirth, participants named emotional stress—not money or medical procedures—as the greatest challenge of becoming a mother.

According to the 2025 World Journal Survey on Health and Well-Being of Immigrant Chinese Mothers in Southern California, more than 25% of participants identified emotional stress as their biggest challenge during childbirth.

(Graphic by Ziwei Liu)

Lily Wang felt the strain of early motherhood deepen after the birth of her second, unplanned child. She spent long days alone with two young children while her husband worked nights. “Back home, I would’ve had family to help,” she said. “Here, everything depends on yourself.” Without a driver’s license in car-dependent Southern California, she often went days without seeing anyone outside her family. “If I could choose again, I might not give birth here,” she said softly. “The loneliness is worse than the pain.”

Small gestures kept her afloat—flowers her husband sometimes brought home, a brief walk when the baby finally slept—but finding professional help felt daunting. “I don’t know much about counseling,” she said. “I don’t have time to think about that.”

Emma Shen, a doctoral student and first-time mother, faced a different kind of strain. The PhD process was already an open-ended marathon—juggling research, filling out applications, and projects that demanded long, unstructured hours. Motherhood turned those hours into fragments.

“Seventy percent of my energy goes to my child,” she said. “The rest isn’t enough to cover everything else.” She often compared herself to her former self. “I used to manage everything. Now I feel inadequate. Maybe I’m not enough.”

A corner of Emma Shen’s daughter’s play area at home. Shen says that after becoming a mother, she has found it difficult to balance childcare with her own personal growth.

(Photo by Ziwei Liu)

Talking with her husband and friends brought little relief. “I wanted to speak with someone who understood both the culture and the motherhood part,” she said. “I haven’t found that person yet.”

Licensed therapist Da Nie, who works with perinatal clients across California, said both stories are common. Stay-at-home mothers, she explained, are often dismissed as “just looking after kids,” yet their days are relentless and isolating. Working mothers fall into another trap: perfectionism. “They’re expected to be model employees and ideal mothers at the same time,” Nie said. “That’s an impossible standard without support.”

Family tensions only deepen the stress. Studies show the first two years after childbirth are the riskiest for new parents’ relationships. Jane Zhang, owner of the Chinese nanny agency, said she sees it often: arguments, silence, husbands absent for weeks. In Chinese households, conflicts with mothers-in-law are especially fraught, particularly in multigenerational homes.

Cultural silence deepens the problem. “In Chinese communities, people talk about the joy of new life, but not the pain or stress,” Nie said. “Mothers fear being judged or seen as abnormal if they seek help.”

Da Nie works with mothers across SoCal and often sees how isolation and perfectionism weigh on them — stay-at-home moms dismissed as “just caring for kids,” and working mothers striving to do it all.

(Courtesy of Da Nie)

Public-health researcher May Sudhinaraset echoed that observation. “Mental-health stigma is really strong in Chinese communities, and that contributes to under-utilization,” she mentioned. “Even though California has a law requiring universal perinatal-mental-health screening, Chinese immigrant mothers in our data were screened at lower rates—63 percent during pregnancy and only 50 percent postpartum.”

“Bottling up negative emotions is never good,” Nie believed. “We need to give them words, and we need to distinguish what’s normal from what’s not.”

Yet even when mothers recognize something is wrong, finding help is another battle. Language gaps, limited insurance coverage, and a shortage of culturally competent providers turn awareness into a dead end for many.

For Fen Chen, the hospital where she first sought help told her their behavioral-health department had no Mandarin-speaking therapists and referred her elsewhere. But the outside providers didn’t take her insurance.

After switching to Medi-Cal, the situation hardly improved: most Mandarin-speaking therapists didn’t take the insurance, and those who did required complex medical forms. It took nearly three months before she found a suitable provider.

Afterward, Chen shared a detailed post on Red Note (known in Chinese as Xiaohongshu), a Chinese social-media platform where users trade personal experiences and advice. Her guide on how to find Mandarin-speaking therapists in California quickly drew thousands of views. “So many people saved it,” she said. “It showed me how many mothers are out there looking for the same thing.”

Even in a state celebrated for its diversity, therapists who understand both language and culture can still be hard for patients to find. “Support exists,” Nie said, “but too often, it’s invisible.”

Light in the Distance

After the sleepless nights, the high costs, and the emotional toll, another challenge remains: getting help that actually reaches them. Public programs and services exist in California, but for many immigrant mothers, awareness and access remain elusive.

Therapist Da Nie said that awareness itself is one of the biggest barriers. “The people who contact me are already ahead,” she said. “They know they’re struggling, they have insurance, and they know where to look. But the ones who need help the most often don’t realize it, or they don’t know where to start.”

Nie hopes for closer partnerships between therapists and community organizations—public workshops, small support groups, and bilingual outreach—to make the first step less intimidating. “If we can bring information into the spaces mothers already trust, we can lower the threshold for help,” she proposed.

In California, public programs exist but often fail to reach those who need them most. Therapist Da Nie says many immigrant mothers lack the awareness or access to seek help.

(Courtesy of Fen Chen)

That lack of visibility extends beyond mental health. Jack Cheng, chief operating officer of the Chinatown Service Center, said California still lacks a comprehensive system for childcare support. “Childcare is one of the fastest-growing household costs, but policy hasn’t kept pace,” he pointed out.

Programs such as Head Start—a federal early-education and care initiative for low-income families—and local options like Options for Learning do exist, but they’re often poorly publicized and come with long waiting lists.

Fen Chen is enrolled, though didn’t know about the programs until another mother told her about them. She eventually enrolled her younger child in a daycare with a subsidy. “The problem is the lack of transparency,” she said. “You don’t know where to look or what you qualify for until someone tells you.”

Her experience is common: applications stretch across agencies, and income thresholds exclude many working-class families who earn just above the line.

In the absence of clear pathways, many mothers turn to social media and chat groups, where advice on insurance, childcare, and counseling circulates informally. These digital communities fill an essential gap, offering empathy where institutions fall short. Yet the information is fragmented, dependent on luck and word of mouth.

For Lily Wang, that uncertainty feels familiar. She still thinks of learning, of working again, of making friends in this new country she now calls home. “Since we’ve come all this way, I want to make something of it,” she said. “But for now, there’s hardly a moment left for myself.”

To help bridge the information gap for Chinese immigrant mothers in Southern California, the reporter created “Mom Support LA” — a Mandarin-language guide to maternity resources and public programs in Southern California: https://www.momsupportla.com/