Part 1: For Cambodian and Vietnamese immigrants, multiple barriers prevent access to culturally sensitive healthcare

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Agnes Constante, a participant in the 2020 California Fellowship, that explores the implications of the lack of access to culturally competent and sensitive health care among Southeast Asian Americans.

Her other stories in this series include:

Part Three: Addressing a lack of culturally sensitive healthcare for Cambodian and Vietnamese communities in O.C.

Cindy Sicheang Phou of the Cambodian Family Community Center leads a breast health education workshop, funded by Susan G. Komen, to bring awareness of breast health to the Cambodian American community.

(Courtesy of the Cambodian Family staff)

This is the first story in a three-part TimesOC series “Improving Healthcare Access for Cambodians and Vietnamese,” which was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2020 California Fellowship.

Angkearoth Leap didn’t understand why she was receiving injections as she was giving birth to her first child in 2013.

Her medical team didn’t explain the purpose of the injections. They caused her discomfort and pain, but she wasn’t able to communicate what she was experiencing to her doctors and nurses.

Leap, 47, had immigrated to the United States from Cambodia in 2002 and had limited English proficiency, making it difficult for her to understand exactly what was going on around her and follow their instructions while in labor.

She arrived at the hospital on a Tuesday morning, but it wasn’t until Wednesday evening that her medical team decided to perform a C-section and the entire ordeal came to an end. She had been weak, she believes, because she was instructed not to eat for the majority of her time in labor. Coupled with thyroid issues, she was unable to give birth naturally.

“It was just a long duration of not knowing what’s the process, not knowing what to expect, and not understanding what is given to you and how to communicate your needs,” Leap said through an interpreter, Cindy Sicheang Phou, program coordinator and former health navigator at Santa Ana-based nonprofit the Cambodian Family.

“It’s just a very, very uncomfortable situation to be in.”

Leap is one of the more than 2.5 million Southeast Asian Americans living in the United States. Orange County is home to approximately 195,000 Vietnamese and 7,000 Cambodian residents, according to figures referenced in a 2010 report by nonprofits Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Orange County and Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance.

The group’s history in the country dates back to 1975 following the conclusion of conflicts in the region: The Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia ended in 1979, and the Vietnam War ended in 1975.

Yet despite a presence of nearly half a century in the United States, Cambodians and Vietnamese continue to struggle with social inequities, including access to culturally sensitive healthcare.

Language as a barrier to healthcare access

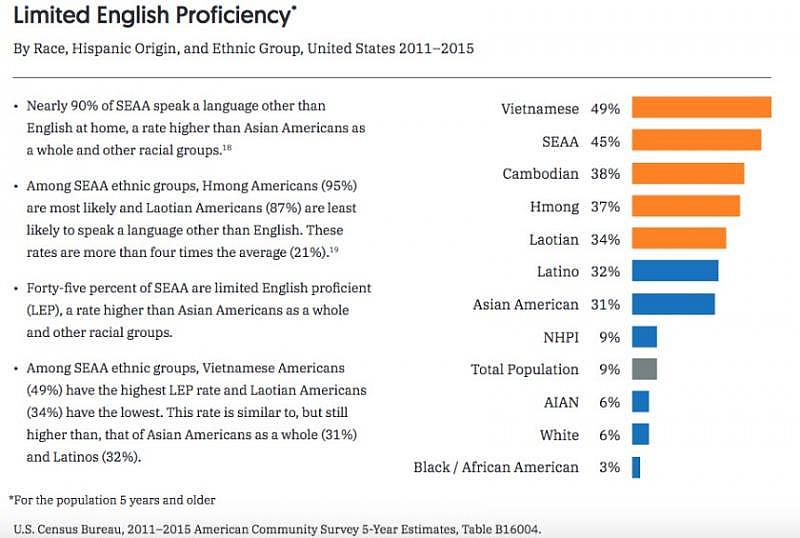

A report from civil rights nonprofit the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center found that about 90% of Southeast Asian Americans speak a language other than English at home, while 45% have limited English proficiency.

Patients with limited English proficiency have been found to experience lower quality of care and high rates of medical errors with worse clinical outcomes than those who are English proficient, according to the American Medical Association Journal of Ethics. One study cited by the medical journal the Annals of Family Medicine found that one out of every 40 malpractice claims were in part or entirely linked to providers’ failure to provide appropriate interpreting services.

In one case, the use of a 9-year-old Vietnamese girl and her 16-year-old brother as interpreters for their parents resulted in the girl’s death due to a reaction to a drug, whose side effects were not explained to her parents. An expert witness testified that they believed the doctor and facility’s failure to provide a professional medical interpreter was a significant contributor to the girl’s death.

Xiomara Armas, chair of the National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters, said language access in healthcare is a critical component of patient safety.

“Everything in healthcare relies on communication,” she said. “Medical providers cannot do their job if they cannot communicate with their patients. And on the other side, the limited English proficiency patients cannot have the care they are expecting if they cannot clearly communicate with their healthcare provider.”

Federal and state law requires providers to have qualified medical interpreters available for limited English proficient patients, though in some cases, they aren’t aware of their right to an interpreter.

That was the case for Leap as she gave birth to her first child. She said her doctors and nurses didn’t inform her about interpreting services available to her.

“The staff probably assumed that because I was able to communicate a little bit that I could speak and understand English,” she said. “However, they didn’t really think carefully about not being able to understand the different terminology in the process of everything.”

While the law requires providers to use qualified medical interpreters when needed, a 2018 study in the journal Annals of Family Medicine encourages providers to use interpreters certified by the National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters or Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters, two entities in the United States that offer formal certifications in medical interpreting.

Both the board and commission established their certification programs in 2009. But more than a decade later, the number of certified Vietnamese and Khmer interpreters remains sparse.

Twenty-two Vietnamese medical interpreters across the U.S. are certified by the board, eight of whom are based in Orange County. The commission has six certified Khmer interpreters, none of whom are in California, and 95 certified Vietnamese interpreters.

Tyler Nguyen, a court interpreter in Sacramento and a certified Vietnamese medical interpreter who previously worked in Orange County, said there’s a stark difference in the quality of interpreting and translating services provided between certified and noncertified interpreters. The training he underwent allowed him to interpret more quickly and improved his familiarity with medical terminology, he said.

Ryan Le, a certified Vietnamese medical interpreter who serves patients in Los Angeles and Orange County, said the board’s program trained him to navigate situations when he has to interpret terminology that doesn’t exist in Vietnamese — such as the word steroid. He does this by asking the doctor to explain the terms in a way he can explain them to patients. He also learned that accurate interpreting is more about conveying the meaning of what’s being said rather than word for word.

Understanding and mastering cultural nuances

The lack of providers with an understanding of patients’ culture is another significant barrier to healthcare access

Phou, the program coordinator at the Cambodian Family who previously worked as a health navigator for the agency, said it’s crucial for providers serving the Cambodian community to understand its experiences and culture, including trauma that refugees have endured as a result of fleeing the Khmer Rouge, the importance of holistic care — which may include practices such as temple visits for healing — and the idea of obligation and duty to family.

Phan Eng, 67, was tortured multiple times and nearly beaten to death by the Khmer Rouge regime before she fled Cambodia, she said through interpreter Kieng Seng, a health navigator and case manager at the Cambodian Family. Her experiences left her traumatized with nightmares, memory loss and sadness.

But when she initially sought medical care in the United States, her diagnosis was unclear, and she was simply prescribed with medication for sleeping and relaxation, she said.

Amina Sen-Matthews, health program director at the Cambodian Family, where Eng is a client, said her symptoms point to post-traumatic stress disorder.

“Providers need to understand that it’s hard to work with our community sometimes because we have been through a lot,” Phou said.

She also noted that providing sensitive care goes beyond cultural and linguistic nuances.

“Each patient is not a case,” she said. “It’s a relationship.”

Leap, who was one of Phou’s clients, said Phou has become like a younger sister to her. Phou provided support while Leap underwent treatment for breast cancer, when she was diagnosed in 2017.

Leap has a young child and a husband whose sole income supports the family. Because he had to work while she fought cancer, it was Phou who was by her side.

“I’ll forever remember her for being there for me and providing all the different care coordination that a patient would ever want,” she said.

Dr. Tony Nguyen, founder and CEO of 360 Healthcare, a group that caters to the geriatric population in Orange County and serves predominantly Vietnamese patients, said he has noticed that the community is drawn to providers that speak Vietnamese and understand the culture, which can encompass belief systems and family dynamics.

“Some families don’t believe in withdrawing care because it’s their religious belief that when it’s time to go, God will take you,” he said. “But if you withdraw care, they think, ‘You kill my mom. You killed Dad.’”

When it comes to handling end-of-life care for Vietnamese patients who aren’t able to make decisions for themselves, Nguyen makes it a point to consult with all of their children rather than putting the responsibility on one person. He said he also understands how to navigate situations where a child, who may have been absent from caring for their parent as their health deteriorated, may insist on prolonging that parent’s life out of guilt.

Le, the certified Vietnamese medical interpreter, said that beyond his ability to speak the language, his understanding of certain facial expressions that can indicate things such as their preferences and dislikes, has also been instrumental in his ability to interpret accurately.

Health education and transportation barriers

In California, heart disease, cancer and stroke are the three leading causes of death in the Southeast Asian American community, according to a report from the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center and Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Los Angeles.

But community members’ lack of awareness of preventive care and how to take care of their health is another obstacle to healthcare for the Cambodian community, Phou said. The Cambodian Family works to address this by hosting a program that promotes preventive health practices, and health education workshops about conditions prevalent in the community, including heart disease and stroke, as well as breast health.

Yet even when patients are aware that they need to seek medical care, the lack of easy access to transportation can make it difficult for them to do so.

Phou said the elders that the Cambodian Family serves prefer to seek and receive assistance from the agency rather than burden their children by asking for help.

“Some of them don’t even trust their kids because they don’t know if they know enough English, where to go, what’s happening,” she said. “So they’d rather come to our agency where they know this is what we do. We do have the language capability to figure it out and help them.”

Phou also noted that the transportation barrier isn’t due to a lack of resources. It’s more that community members aren’t always aware of what is available to them and aren’t always comfortable accessing them.

The agency CalOptima provides a number of services for Medi-Cal patients, including transportation and language lines for those who have limited English proficiency. But Phou said even requesting for an interpreter requires patients to speak enough English.

Yet simply asking for a “Khmer interpreter” can be uncomfortable for many, she said.

“Even sometimes when you teach them, ‘When you call, you put this number and then you dial the extension and then you just say one simple line: Khmer translator,’ it’s still a very difficult process,” she said. “When it comes to documentation, healthcare, speaking English, they’re not comfortable with it. And they always want someone there with them to assist.”

For elders who rely on their children to get to the doctor, the situation can be financially challenging. Census data referenced in a report published by civil rights nonprofits the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center and Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Los Angeles highlighted that the average per capita income for Southeast Asian Americans ranges from about $17,000 to $23,300.

Westminster resident Hong Vuong’s income supports her parents, brother and sister-in-law, so taking even one day off to bring her parents to the doctor is not something she can afford to do easily, she said.

Last year, she placed her parents under the care of Dr. Tony Nguyen’s practice 360 Healthcare. Providers in that group travel to see their patients rather than vice versa, which Vuong said has eliminated that burden.

“They come to your house, and that saves a lot of time,” she said. “My parents don’t have to worry about getting sick from the virus of other people. The doctors come and do X-rays and they do blood tests here. It’s very convenient.”

Impact of lack of culturally sensitive healthcare providers

The struggles resulting from a system that lacks culturally sensitive and appropriate healthcare extend beyond patients to the limited number of providers and individuals serving to bridge that gap.

Dr. Tony Nguyen said he sees about six to eight patients per day, a fraction of the 20 to 30 a provider at a hospital practice might see on a daily basis. Yet even with a smaller number of patients, people frequently contact his practice outside of clinical hours, he said.

So he’s always trying to recruit physicians and nurse practitioners to join his team.

“The phone always rings off the hook,” he said. “It’s a very demanding operation.”

Vattana Peong, executive director of the Cambodian Family, said bilingual and bicultural health navigators have proven to be an indispensable piece in ensuring culturally sensitive healthcare access for the Cambodian community.

But with only 10 at the agency, each of whom handles a case load of anywhere between 10 to 15 clients, demand for their help is high.

Phou said clients are heavily reliant on health navigators for assistance, in part because they trust and are comfortable with the agency, she said.

She remembered asking a group during a workshop who they would call in the event of an emergency. The resounding response was the Cambodian Family.

“Sometimes it can be very, very overwhelming because we just want them to do a direct utilization of the services and programs so we can focus on people who really don’t know how to use them,” she said.

“When it comes to crises, we cannot be the ambulance. We can do a lot of things, but some things we just can’t do, and this is where we would like to let them know, these are lines you can call to get those resources and needs met,” she added.

The lack of a bicultural and bilingual medical workforce is a root cause of the issue, Peong said. It’s something that has been difficult to address due to low graduation rates in the community: 17% of Cambodians hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, compared to 30% of the total U.S. population. It’s a statistic that’s attributable to barriers such as poverty and the lack of access to educational resources.

For now, it’s health navigators filling the gap in healthcare access for the Cambodian community, and it’s a solution that has been working effectively, Peong said.

“We still have hope to fix the root causes, but the community members we are assisting, almost 35 percent are 65 and older, and they cannot wait for another 10 to 15 years,” he said. “Their health is getting weaker and weaker. We cannot wait for that long.”

The next story in the “Improving Healthcare Access for Cambodians and Vietnamese” series will address mental health in these communities.

[This story was originally published by TimesOC].