Part 2: Mental healthcare for Cambodian, Vietnamese refugees limited by shortage of bicultural, bilingual providers

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Agnes Constante, a participant in the 2020 California Fellowship, which explores the implications of the lack of access to culturally competent and sensitive health care among Southeast Asian Americans.

Her other stories in this series include:

Part Three: Addressing a lack of culturally sensitive healthcare for Cambodian and Vietnamese communities in O.C.

Viet-CARE members and other participants at the third annual Asian & Pacific Islander Mental Health Empowerment Conference gather in front of a pickup truck that commemorates veterans, who are a vulnerable population to mental health challenges.

(Andrew Nguyen / Viet-CARE)

This is the second story in a three-part series in the Daily Pilot, “Improving Healthcare Access for Cambodians and Vietnamese,” supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism 2020 California Fellowship. The first story was about barriers to culturally sensitive physical healthcare.

The Center’s engagement editor, Danielle Fox, contributed engagement support to this story, including setting up four listening sessions with 46 members of the Cambodian and Vietnamese American communities.

(My Tien Pham)

Paul Hoang moved to Orange County in 2007 after a taxing work year as a mental health clinician in Illinois.

In the Midwest, he had seen clients who drove up to six hours once a month — even through blizzards — for his services. Demand was high because there was a lack of providers serving the Vietnamese community, he said.

It was something he tried to remedy by getting involved in local politics to advocate for more resources.

But after a year, he burnt out.

Hoang had hoped to find more groups that served the Vietnamese community and more support for providers in Orange County, given its Vietnamese population of approximately 200,000, according to the 2010 census. He said he arrived surprised to find that neither of those things existed.

“It was very scattered and people were working in silos,” Hoang said. So in 2008, he founded Viet-CARE, a group of mental health professionals working to end the stigma attached to mental health and to address mental health disparities. He also established the group in part to create a space of support for bilingual and bicultural Vietnamese mental health providers.

Paul Hoang founded Viet-CARE, a group of mental health professionals serving the Vietnamese American community, in 2008.(Courtesy of Viet-CARE)

The need for mental health services in the Vietnamese community is high, Hoang said. But there’s a strong stigma attached to mental health in the community, and members aren’t always able to access the type of services they need.

It’s a similar circumstance faced by the Cambodian community, which in 2010 accounted for about 7,000 of Orange County’s population, according to census figures at the time referenced in a report by nonprofits Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Orange County and Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance. In nearby Long Beach, Cambodians constitute an estimated 20,000 of the city’s population.

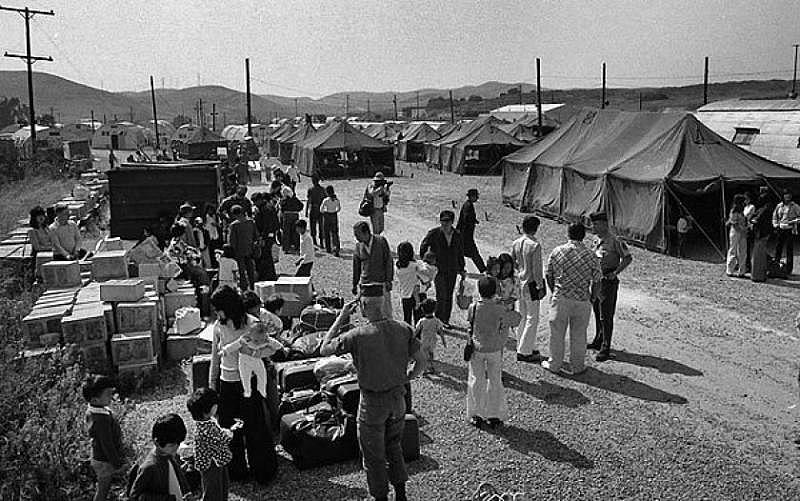

Vietnamese and Cambodians began migrating to the U.S. en masse after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 and the 1979 fall of the Khmer Rouge regime, under which more than 2 million people died.

The experiences of fleeing war-torn nations has had a lasting impact on refugees’ mental health.

A 2015 study in the journal Psychiatric Services found that 97% of Cambodian respondents met criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder. Available data on mental health issues facing Vietnamese refugees — much of which is several years to more than a decade old — show that they suffer from issues including PTSD and panic disorder.

But Hoang said there is a lack of services that account for the unique experiences of the community, which affects both community members in need and the limited number of bilingual and bicultural providers that are able to serve them.

The relocation center in the Cristianitos area of Camp Pendleton. Many refugees housed at the base decided to stay in Southern California for the warm weather that they were accustomed to in Southeast Asia. (Photo by Don Bartletti)

Roots of trauma

Hoang was among the hundreds of thousands of refugees who fled Vietnam after the end of the Vietnam War. Many escaped via boat or foot, experiences that are often a source of trauma for refugees, he said.

He recalled his own experience as a kid of being out at sea on a fishing boat with more than two dozen others for nearly 30 days. In that time, the passengers were attacked by pirates three times, and they reached the point of hunger where people began talking about killing others for food, he said.

The trauma from that period of time persisted for him and his family even after they settled in the United States.

“I remember hearing my dad screaming every night,” Hoang said. “Every night at midnight, I would go to his room and put my ear on his chest just to make sure that he’s still breathing. That’s common for us who are refugees.”

Phan Eng, 67, a client at Santa Ana-based nonprofit the Cambodian Family, came to the United States in 1985 as a refugee after fleeing the Khmer Rouge regime. Through an interpreter, Kieng Seng, a health navigator and case manager at the nonprofit, Eng said she remembered being put into a plastic bag and being beaten nearly to death. Her life under the regime led her to have nightmares every night, she said.

When she arrived in the United States, Eng began noticing that she experienced memory loss and often felt sad. She went to a doctor to find out what was wrong, but her diagnosis was unclear.

She was prescribed medication for sleeping and relaxation. Amina Sen-Matthews, health program director at the Cambodian Family, said her symptoms point to post-traumatic stress disorder.

The trauma refugees experience can be transferred to their children and grandchildren through intergenerational trauma.

Long Beach resident Jocelyn Ly, 23, said her grandfather’s experience fighting against the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia trickled down to the dynamic she has with her father, who was born in a refugee camp.

Ly believes his experience at the camp, coupled with the way he was raised by his parents, affected the way he parented her and her two sisters. He was emotionally absent, she said, and it was difficult for her to not have a strong bond with her father.

“How can you tell someone your experiences, but they don’t know how to handle their own?” she said.

A common way Hoang has seen intergenerational trauma manifest is in parents’ anxieties around law enforcement, with whom refugees have had negative experiences in Vietnam.

While they may not have had those experiences in the United States, the sight of an individual in uniform can induce flashbacks that retraumatize them, he said.

“Children are taught to avoid cops,” he said. “It’s passed on down through parenting. It’s passed on down subconsciously through how the parents act around them and around in their environment. So the children grow up observing that in their environment and subconsciously take that on and they too become anxious when they’re around police.”

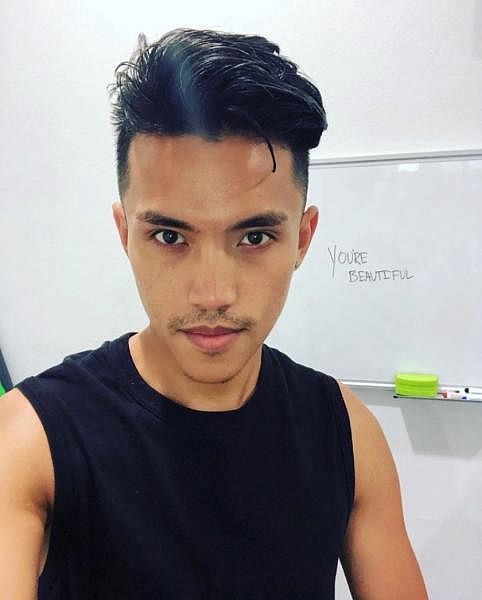

My Nguyen is a board member on Viet Rainbow of Orange County (VROC), an organization that advocates for Vietnamese Americans across sexual orientations and gender identities.(Courtesy of My Nguyen)

As a child, My Nguyen, 25, said he endured physical abuse after sharing information with a family member that triggered fear of law enforcement. He said he missed two days of school before he recovered.

“There was a lot of generational trauma and especially war trauma that had been passed down to myself,” Nguyen said. “It was just very, very hard for me to process.”

Hoang added that if a refugee is stopped by law enforcement officers and presents symptoms of anxiety, that may be interpreted as the individual hiding wrongdoing.

“That further escalates because law enforcement here are trained to be in control and not understanding the psychology or mental health,” he said. “When a person is going through fight or flight mode or a panic attack, the mind is not processing normally. That creates a lot of misunderstanding and miscommunication, which then produces a negative outcome, which further reinforces the trauma that law enforcement are bad.”

My Nguyen marches in a Little Saigon rally in 2018 against the Trump Administration’s attempt to change and violate the repatriation agreement between the U.S. and Vietnam. That would have put 8,500 Vietnamese Americans at risk of deportation.(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

Impact of deportations on mental health

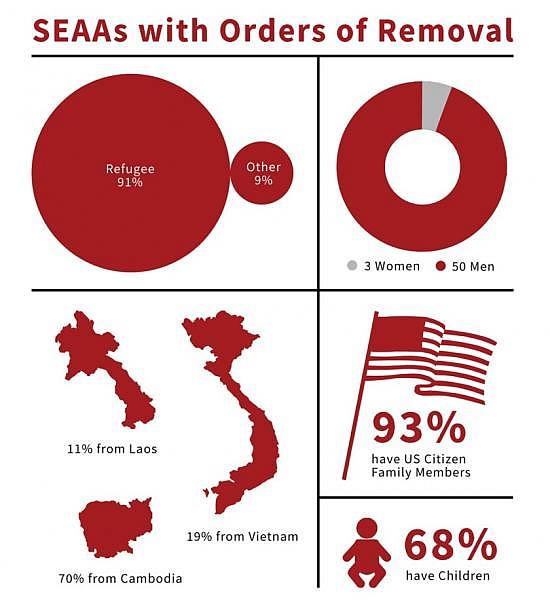

The past traumas, common among Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees, have been compounded in recent years with the rise in deportations from the U.S. in both communities. Between fiscal years 2017 and 2018, Cambodians saw a 279% hike in deportations, rising from 29 to 110, according to data from Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Vietnamese Americans also saw a rise in deportations: In the last three fiscal years, there were 273 removals, compared to 115 from fiscal years 2014 to 2016, data from the agency show.

A 2018 report by nonprofits Southeast Asia Resource Action Center and National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum found that increased detentions and deportations can create financial instability for families — many of whom are low income — contribute to stress and anxiety and cause trauma to children of detainees and deportees.

Long Beach resident Alisha Sim, 23, said she saw her father, who had overcome alcohol abuse, return to the vice as a way to cope after her brother was deported in 2009. The deportation also put financial strain on her family.

Sim’s mother sewed clothes for a living and was paid per article of clothing she completed. After her brother’s deportation, she saw her mother work until 2 a.m. to sew more clothes to earn more money.

By the time Sim got to college, she had to work multiple jobs. She said she needed to be less financially dependent on her parents, whose incomes were strained because they had to provide for their household in the U.S. and for Sim’s brother in Cambodia.

She noted that along with school and work, she served as the caretaker for the elders in her household.

“Going to college was really hard,” she said. “I realized that my grades were dropping. I had to get on academic probation a few times, and instead of going to school full time, I had to go part time to work with my schedule.”

Source: 2017 SEARAC Advocacy Data Collection Forms. Figures are based on a subset of over 50 SEAA respondents who sought support and are not a representative sample of all Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders with deportation orders nationwide. (Alyssa Shea / Southeast Asian Resource Action Center’s “Dreams Detained, in Her Words” report

Gender identity

For some in the Vietnamese community, grappling with gender identity while straddling two cultures is another source of strain on mental health.

After coming out to his mother at the age of 16, Nguyen was kicked out of his house and found himself moving from one place to another, he said. It was an action his mother took that was tied to the cultural value of saving face.

“If I were to be queer, then she was a bad mom, or her ex-husband’s side of the family can say she’s a bad mom,” he said.

His displacement, combined with other stressors and a toxic relationship he was in, led Nguyen to attempt suicide that year.

He grew up in Kansas City where he hardly ever encountered any other Vietnamese Americans and where access to healthcare was difficult. He said he tried group and individual therapy following his attempt but didn’t find either of them helpful because nobody could understand the intersection of his identities as queer and Vietnamese American.

“How are you going to be able to mediate a situation between me and my family if there’s no language resources? Or if there’s no understanding of the power dynamic of the family?” Nguyen said.

Gender identity can also be challenging for parents of LGBTQ Vietnamese.

Several mothers of LGBTQ children told TimesOC that they previously had little to no knowledge of what it meant to be LGBTQ or that such a group exists in the Vietnamese American community.

Loan Nguyen, a former Orange County resident who is not related to My Nguyen, said she initially felt guilt and shame when her child at 11 years old told her that she was transgender. Having grown up in a devout Catholic household that valued conformity, Loan Nguyen said she also experienced embarrassment.

“That’s the Asian culture, the Catholic religion,” she said. “The sense that others will look to you and say you’re wrong: ‘What’s wrong with you? How could you allow this?’”

Those are feelings she said she worked through quickly by learning about gender identity because she knew she had to support her child.

Loan Nguyen now lives in New York where she works as program coordinator at the LGBTQ civil rights group PFLAG NYC. She said families that hold on tightly to traditional practices and customs without acknowledging gender identity can result in oppressed feelings for those who identify as LGBTQ.

“Oftentimes in the name of love, Asian parents will create a lot of harms and mental, emotional pain and suffering for their children,” she said. “They think they know their children best. They will put their foot down and demand a certain way of behavior and acting without understanding where that child is coming from.

“That child will have no choice but to do it out of obedience, out of fear of getting kicked out of the house, out of fear of the religion the parents impose on them. But it’s all through guilt. And where does that go? It goes right into that child’s psyche.”

Minh Tran of Westminster holds a sign and Pride flag as he protests the exclusion of LGBT groups from the Tet parade in Little Saigon in 2013. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)

Barriers to mental healthcare access

Despite the need for mental health services, a number of factors make it difficult for Cambodians and Vietnamese to access them.

During TimesOC’s listening sessions with 46 community members, many shared that there is an insufficient amount of mental health educational resources and many aren’t aware how to navigate the healthcare system to access them.

Others said their introduction to mental health came from their friends and community-based organizations, not from their families. Some said there is a lack of education on how to identify sexual assault, an occurrence that several individuals said is common in the Cambodian community. Many also noted that they weren’t taught in school about the traumas their parents experienced from fleeing from war-torn countries.

Ly said she learned more about the types of experiences her family endured under the Khmer Rouge regime from Long Beach nonprofit Khmer Girls in Action than anywhere else. It was helpful for her to know that history.

“Me understanding that my parents have their own personal trauma or issues that they’re going through doesn’t make me resentful,” she said.

For LGBTQ Vietnamese, one of the barriers is a lack of spaces that accommodate both gender and cultural identity.

“If you’re in a space where you’re queer and people understand you’re queer, but being Vietnamese is foreign, I have to explain myself,” he said. “Like, why do I take my shoes off when I go inside the house? I’m like, I take it off because I’m Vietnamese.”

For monolingual and limited English proficient community members, language is a significant barrier.

Hoang said he witnessed the dangers of poor communication with a former client who was diagnosed with schizophrenia under another provider. He looked over the client’s notes and saw that the diagnosis was made based on poor interpretation conducted by his 8-year-old daughter.

After asking the client a series of follow up questions, Hoang concluded that depression was the correct diagnosis. By then, however, the client had already been on antipsychotic medication for three years, which impaired his ability to function normally.

“Unless the interpreter has a background in mental health specifically, they won’t understand the concept that they’re interpreting or translating,” he said.

Beyond language, there’s the general lack of understanding of the refugee experience, which affects the effectiveness of or referral for mental health treatment.

Members of Viet-CARE, which provides mental healthcare services and advocacy for the Vietnamese American community in Orange County. (Andrew Nguyen / Viet-CARE)

Impact of lack of access on providers

The number of bilingual providers who have an understanding of the experiences and culture of the community are few, Hoang said, which limits access for those who need mental health services.

It also takes a toll on providers.

Chandara Lee, a part-time therapist at the Cambodian Family, said his ability to speak Khmer and being a refugee who fled the Khmer Rouge regime with his family in 1979 enables him to better serve clients who have similar experiences.

He said his understanding of those experiences and Cambodian family dynamics allows him to mediate family issues because he is effectively able to communicate various perspectives across different generations.

Lee previously worked at the Orange County Adult Behavioral Health Services, Crisis Assessment Team for about two decades. He said he was the only Khmer-speaking therapist on the team and rarely ever saw any other Cambodian therapists.

He was offered a full-time position at the Cambodian Family, he said, but opted to take on a part-time caseload of 40 clients. While he could and would like to do more to serve the community’s need, he also wants to slow down after having worked in the field for 21 years.

Amina Sen-Matthews, health program director at the Cambodian Family, said the agency is heavily reliant on its nine health navigators who double as case managers to make mental health services more accessible to the Cambodian community. They educate clients about mental health, accompany them to therapists and psychiatrists and serve as interpreters, all while taking on similar responsibilities to increase access to physical healthcare services.

Support for providers is crucial as well, Hoang said, which is part of the reason he established Viet-CARE. The group offers the limited number of bicultural and bilingual providers who serve the community a space to process with each other.

“How do we take care of ourselves and how do we empower ourselves to take care of ourselves?” he said. “Because in the workplace we experience discrimination by our peers, by our non-Asian community. We experience racism, we experience all types of hardships within ourselves as well. Some individuals, even though they are providers, they have a lot to work through on themselves.”

The next story in the “Improving Healthcare Access for Cambodians and Vietnamese” series will examine efforts to address the lack of culturally sensitive healthcare access in these communities.

[This story was originally published in the TimesOC, the Orange County edition of The Los Angeles Times.]