Part 2: More than ‘a little snip’

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Marina Riker, a participant in the 2020 Data Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

Birth in the time of coronavirus

It's one of the silver livings': How COVID-19 pandemic could boost access to maternal health care

She already had a high-risk pregnancy. Then, COVID-19 struck.

Part 1: Birth on demand

Texas lawmakers aim to make maternal health a priority this year

Part 3: Filling The Gap

Our women are dying': Texas lawmakers urged to extend Medicaid to a year after birth for new mothers

Jerry Lara/Staff photographer

LAREDO — Linda Martinez had been in labor for more than 24 hours when, she said, her doctor told her, “We’re going to cut you a little bit.”

Her obstetrician at Doctors Hospital of Laredo was about to perform an episiotomy — an incision made with surgical scissors through the vaginal opening to widen the birth canal and hasten delivery. During Martinez’s months of prenatal visits and a two-hour hospital birth class, no one ever mentioned the procedure, she said.

Then, suddenly, it was happening — to her.

“They just made it seem like, ‘Oh it’s just a little thing, a little snip and that’s it,’” Martinez said of the medical staff who handled her delivery in September 2019.

Nothing could have prepared her for the pain she experienced after birth, she said. She described it as 8.5 on a scale of 10. The first-time mother, then 19, feared the stitches would suddenly split apart: “I was really scared to go to the restroom — like really scared,” she said.

Episiotomies were once commonplace. Forty years ago, doctors in the U.S. performed them in more than 60 percent of vaginal births. But evidence accumulated that they can do more harm than good, causing intense pain and the potential for serious long-term complications including loss of bladder and bowel control.

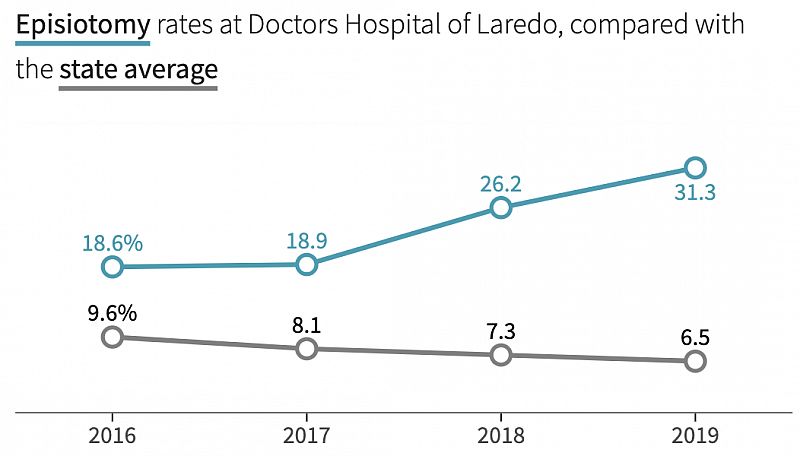

Despite this guidance, Laredo’s two hospitals performed episiotomies at rates four to six times the recommended level last year, according to an Express-News investigation conducted with Christian McDonald, a data journalist who teaches at the University of Texas at Austin’s School of Journalism and Media.

McDonald analyzed hospital billing data to determine the rate of surgical interventions during childbirth at Texas hospitals.

Doctors Hospital of Laredo in 2019 had the highest episiotomy rate among all nonmilitary hospitals in Texas: The procedure was performed in 31 percent of vaginal births.

At Laredo Medical Center, the episiotomy rate was 19 percent.

The average for Texas hospitals was less than 7 percent.

There is no national standard for episiotomies, but the Leapfrog Group, a national nonprofit that analyzes data on hospital safety and quality of care, recommends a rate of no more than 5 percent.

“If you get to the core of the matter — why on earth are doctors performing episiotomies unnecessarily? It’s impatience,” said Dr. Steven Clark, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston who has spearheaded efforts to reduce episiotomies.

“When a woman comes to a certain point in pushing the baby out, in many cases you could either continue to let her push for another half hour — or cut an episiotomy, deliver right now and you’re done.”

The 326-bed Laredo Medical Center, the city’s largest hospital, told the Express-News in a statement that it’s working with its obstetricians to review internal data on episiotomy rates.

“Although guidance from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology has evolved over time, valid reasons remain for why physicians perform the procedure,” the hospital said.

Doctors Hospital of Laredo is a 183-bed, for-profit institution partly owned by the physicians who practice there. The chief obstetrician, Dr. Juan Montalvo, said the hospital significantly reduced the frequency of episiotomies this year — from 34 percent in December 2019 to 14 percent by summer.

A GBH News analysis found that more drug trials went toward treating erectile dysfunction than preterm birth in women. The disparity was more striking when narrowed to industry-funded trials. Data: GBH News analysis of clinicaltrials.gov; data visualization by Hannah Reale

The hospital did not provide its data to the Express-News, however. The state of Texas, which collects data on hospital procedures, has not yet made statistics for 2020 available.

The reduction in episiotomies at Doctors Hospital was driven by a requirement that hospitals meet state-designated standards for maternal care in order to qualify for Medicaid reimbursements starting next September.

Martinez delivered a healthy baby boy and has suffered no serious complications. But it gnaws at her that neither the procedure nor its potential long-term consequences were explained to her ahead of time.

She said that although she’d signed a general consent form when she had arrived at the hospital the day before, she was not told why the episiotomy was being performed or the risks and benefits.

By the time the doctor made the incision, she’d been having contractions for more than a day, was on pain medication and had eaten nothing but ice chips.

“I do remember signing, but I honestly don’t remember what they said because I was already in labor,” said Martinez, now 20. “My mind was somewhere else.”

Martinez’s physician, Dr. Eliud Acevedo, did not respond to requests for comment, and the hospital said it would not comment on individual cases.

Abraham Saavedra plays with son Samuel Saavedra as Linda Martinez watches. Martinez, who’s now a doula, says she wants to make sure that other mothers know they can speak up in the delivery room. JERRY LARA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Montalvo, speaking in general terms, said, “An episiotomy is done at that moment when it’s needed — it’s not like we did it because we wanted to.

“It would be somewhat medically inappropriate to stop the process … to say, ‘Ma’am, can I cut an episiotomy?’” he said.

“Trying to get the patient to decide medically what to do,” he added, might even constitute “malpractice.”

Authorities in the field do not see it that way.

Dr. Tony Ogburn, chair of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, said that even in the delivery room, there’s usually time to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of an episiotomy.

Circumstances in which a physician wouldn’t have time because the mother’s or the baby’s life was at risk are exceedingly rare, he said.

“I haven’t cut an episiotomy in 10 years, honestly. I am convinced it is better not to,” Ogburn said. “Are there rare circumstances where the baby’s heart rate is down and you want to expedite? I certainly understand the circumstances where you’d want to do it, but they are very uncommon.”

Dr. Shanna Combs, an obstetrician who oversees the OB-GYN rotation for medical students at the Texas Christian University and the University of North Texas Health Science Center School of Medicine in Fort Worth, said the risks and benefits of the procedure — and those of other possible interventions including vacuums and forceps — should be discussed during prenatal care, long before a woman arrives at the hospital in labor.

Combs said she has performed episiotomies in fewer than 10 deliveries out of the more than 1,000 she’s overseen during eight years of practice.

“At the end of the day, the mother has the right to refuse,” Combs said. “She’s the one who makes the consent, no matter how strongly you feel about it.”

From the start of 2016 to the end of 2019, physicians at Doctors Hospital performed episiotomies during more than 830 births.

Montalvo said one circumstance that calls for the procedure is if the baby is “too large” and would cause “much more damage” to the mother if she were to tear.

But medical experts said the belief that episiotomies heal more easily than most natural tears is outdated — and so is the assertion that a “big baby” would necessitate the procedure.

“First, we don’t know how big the baby is because it hasn’t been born yet,” Clark said. “Second, yes, big babies take longer to deliver, no question. But unless there’s a reason to hurry it, go ahead and take longer.”

Unlike with C-sections, a high-risk pregnancy shouldn’t increase a mother’s chance of needing an episiotomy, Clark said. The procedure should be performed only if there’s a dire medical need, such as a sudden deterioration in the mother’s or baby’s condition.

Some Texas hospitals have slashed the number of episiotomies by educating physicians and sharing data within hospitals that show how doctors’ rates compare with those of their peers.

Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, where Clark practices, reduced its rate from 9.1 percent in 2014 to less than 3.4 percent in 2017.

“Hospitals can do this,” said Clark. “But again, it takes a concerted effort between medical staff and administration to say, ‘We’re going to stop doing these, and we’re not going to take the excuse any more by the doctor who’s in a hurry.’”

‘Oh, you feel that?’

Throughout much of the 20th century, doctors believed surgical incisions were safer and easier to stitch than natural tears. But by the 1990s, research began to show the opposite: that surgical cuts can go deeper into the muscles, causing more postpartum pain and, potentially, loss of bladder and bowel control.

“The problem with that is when you’re already surgically opening the area there, then as the woman is pushing and going through labor, then she can further tear,” said Lauren Steele, an Austin-based physical therapist.

It’s very common for women to tear during childbirth, Steele said, and those tears often heal on their own and don’t lead to long-term problems.

The serious complications often arise when episiotomy incisions extend farther than natural tears would, damaging the muscles that control bowel, bladder and sexual functions. It’s estimated that women who receive episiotomies are about 1.7 times more likely to have anal incontinence.

“I have worked with women who have been in their 70s and 80s who have had episiotomies way back when, and they still have issues,” Steele said. “I still consider those patients to be my ‘postpartum patients’ because these are postpartum issues that have never been treated before.”

Doula Kristi Dixon Pride supports Candice Phillips while she labors. As part of her job, she tells her clients that medical professionals need to ask permission and explain the risks and benefits of procedures before performing them. JERRY LARA/STAFF PHOTOGRAPHER

Almost 74,000 episiotomies were performed in Texas hospitals between 2016 and 2019, in nearly 8 percent of vaginal births. Neither the state of Texas nor health care oversight groups track how many of those mothers suffered complications.

“They need to ask you before doing an episiotomy, or explain things and then let you decide because ultimately, you have the final say,” said Kristi Dixon Pride, a doula who practices in San Antonio.

Pride said she didn’t have the final say — let alone knowledge of what was happening to her — when, in 2008, she gave birth to her first child in a U.S. military hospital overseas.

Pride, a sexual assault survivor, had been anxious about childbirth and was in the middle of pushing when she felt a sharp pain.

She cried out.

“Oh, you feel that?” her doctor replied, then set the surgical scissors back down on the table.

Pride’s experience giving birth altered her life. Five years after her first son was born, she enrolled in a class to become a doula — a trained professional who provides support before, during and after childbirth. Research has shown the presence of a doula can lead to shortened labors, fewer C-sections and decreased need for pain medication.

In the last five years, Pride has supported women during nearly 300 births. As part of her job, she educates her clients about what informed consent means: that medical professionals need to ask permission and explain the risks and benefits of procedures before performing them.

Although episiotomies are becoming less common, Pride said she needs to whisper in a client’s ears every so often when a physician reaches for the surgical scissors, so that patients who don’t want an incision have the opportunity to say so.

Pride said that in one case involving a client of hers, the physician performed an episiotomy without telling the patient.

The woman didn’t find out until a surgical tech told her after the delivery.

“Those little subtle things that seem little to the staff are really big things to people and what they have to live with, because it’s their body,” Pride said. “Just because you’re there and you’re trying to push a baby out of a vagina doesn’t mean that your vagina is just open to everyone to come in and do whatever they think they have to do.”

‘Come out already’

Martinez said that after she gave birth, she didn’t know whether the agonizing pain from her episiotomy was normal. No one had told her what to expect. Her only directions from medical staff were to avoid wiping with toilet paper and to use water to clean the area.

Nine months earlier, Martinez had wanted to hire a doula. But there were none in Laredo. So, like Pride, she decided to become one. She enrolled in an online course.

During her training, she reflected on her own birth experience and came to believe the episiotomy could’ve been avoided.

“I think it was just the doctor wanting the baby to come out already,” she said.

Martinez, a student at Laredo College, wants to make sure other mothers can speak up in the delivery room. After receiving her certification in July, she appears to be the first doula in the city of 260,000.

“Even if you think you know your doctor is the almighty and powerful,” Martinez said, “your voice is much more powerful.”

[This story was originally published by San Antonio Express-News.]