Part One: How Prince George’s County Adapts To Having The Fourth Highest Number Of Unaccompanied Minors In The U.S.

This story is part of a larger project by Kavitha Cardoza, a participant in the 2019 National Fellowship, who is exploring the unprecedented challenges education professionals must address when they attempt to create and manage programs and services to support undocumented children who are navigating life in a foreign country.

Her other stories include:

How Prince George’s County Is Adapting To A Growing Number of Unaccompanied Children

Listen To Part 4: Prince George’s Schools Welcome Undocumented Students By Respecting Their Past

Last year, the Office of Refugee Resettlement placed 1,558 children in Prince George’s County – the fourth-highest number after Harris County, Texas, Los Angeles and Miami-Dade.

Tyrone Turner / WAMU/DCist

Nando was in the fourth grade when his older brother was killed by gangs in El Salvador. His mother was terrified for his safety, so Nando stopped going to school. For years, he stayed indoors.

“It felt like prison,” he says.

Nando’s family struggled to put food on the table. They grew increasingly desperate. So at 16, he decided to make the treacherous journey to the U.S., leaving behind his parents and younger brother.

“I had a coyote who was helping me but halfway through, he took my money and left,” says Nando about the man who helped him navigate the border crossing. He worked on a farm in Mexico for two months to make enough money to continue the journey. “I was sad, I was tired, I felt desperate.”

He applied for political asylum in the U.S., and after six months in two detention centers, his aunt sponsored him. She lives in Prince George’s County, Maryland – which last year accepted the fourth-highest number of unaccompanied immigrant minors in the nation. He arrived in January that year. Nando is his middle name; he asked that his full name not be used to protect his privacy and safety.

He was just settling into a routine at school when he learned gangs had murdered his other brother.

“We were three. Now it’s only me,” he says.

There has been a dramatic increase in the number of children like Nando fleeing poverty and violence in Central America since 2013. The Trump administration tried to curb this trend by expanding detentions, increasing family separations, narrowing asylum criteria and canceling funding for their legal representation. But between October 2018 and September 2019 more than 75,000 unaccompanied minors — children who arrived in the U.S. without a parent or guardian — and almost 475,000 families with children crossed the U.S.-Mexico border.

That’s a whopping 369% increase in the number of people who crossed the southern border since the same time in 2017. And these are just the people who are known to the Office of Refugee Resettlement: The actual number of people who enter the U.S. every year is much higher.

Most of the attention has focused on the poor conditions and children’s traumatic experiences in detention centers. But it can take as long as five years for their asylum cases to wind through the backlogged legal system after they are released to family members or sponsors. During that time, like other immigrants in the U.S. without official sanction, they are considered “undocumented.” Meanwhile, they are legally allowed to enroll in U.S. public schools, and many do. Schools are often the first place the children encounter Americans who are not law enforcement. And while not all schools are welcoming to these kids, it’s often the first place many say they are treated with kindness.

A hand painted sign in the hallway of the International Student Admissions and Enrollment office in Prince Georges County. Tyrone Turner / WAMU/Dcist

In some school districts, educators had begun going further before the pandemic hit, intentionally overhauling their programming and moving around resources to help these children succeed.

When Nando found it profoundly difficult to make it through each day and considered giving up on school, his school’s social worker talked with him individually and encouraged him to continue. His guidance counselors and teachers have been supportive of him, he says, and his days became a little brighter when he began to make friends.

Patricia Chiancone, who oversees Prince George’s County Public Schools’ programs for international students, says the district enrolled fewer than 4,000 international students 10 years ago. In the spring of 2020, even with coronavirus-related travel restrictions in place, it enrolled more than twice that number.

Patricia Chiancone oversees Prince George’s County Public Schools’ programs for international students. Tyrone Turner / WAMU/Dcist

Chiancone says she expects the number of international students in the district to climb even higher next year. “I absolutely think that the numbers will go right back up when the pandemic passes. No doubt,” she says.

Having so many children arrive throughout the year who are encountering a new language, new culture and new family life can be a tremendous strain. Many undocumented students struggle with basic needs like food, housing and health insurance. Chiancone says many also have an “interrupted education” or large gaps in their schooling so they are academically behind, even in their home language.

But what might be the single most defining characteristic of this population is the considerable trauma they’ve experienced — in their home countries, during their journey here and after they reach the U.S. That’s why the school system has placed a particular emphasis on mental health and counseling, with several schools carving out resources to hire additional counselors.

Compounding these is the coronavirus pandemic, which forced the entire state to stop in-person teaching in March. Teachers talk about how difficult it is to develop relationships online. Some of the districtwide language initiatives, such as using visual aids and hands-on learning, are almost impossible for students with poor internet connections, without basic supplies like paper or pencils or with a baby crying in the background.

But Nando and his family have more immediate concerns.

His mother texts him just to make sure he’s still alive. He lives alone in a rented room and has a part-time job after school where he works from 4 p.m. to 1 a.m. “I need money for rent, food and clothes. I send $300 to my mother every month, I have to pay my lawyer $6,000 for my case.” He laughs wryly. “Yes, I’m very tired.”

He’s thought about dropping out of school several times, but each time he returned because he wanted to show his mother he could achieve something. “I wanted to do this for her,” he says. “We miss each other so much.”

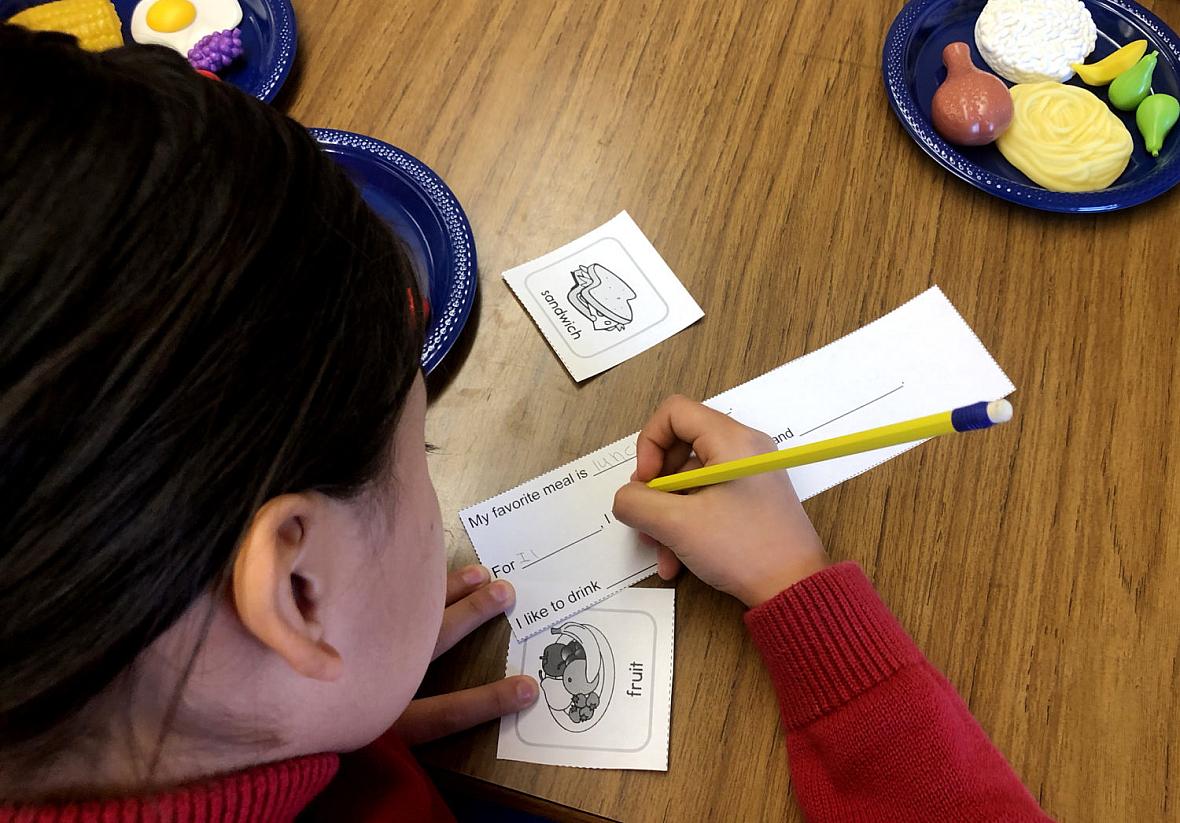

Tanya Gan Lim teaches a “newcomer class,” which the district created for children who have been in the U.S. for less than a year and are learning English. They focus on themes the children use in everyday life such as the weather, body parts and transportation, to help them build vocabulary.

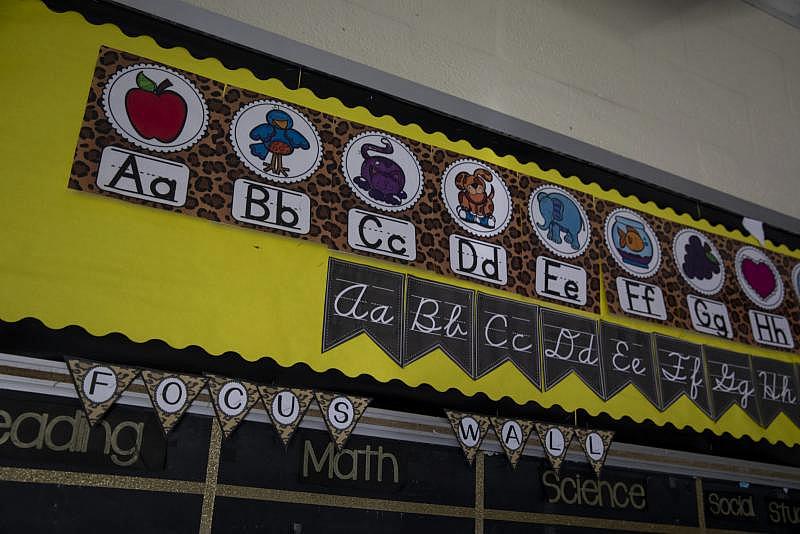

Learning English is an obvious but critical step. Apart from succeeding academically, it’s a way to make friends, translate for their parents and navigate their new culture. It’s also a way to share their story and feel like they belong. In August 2019, Prince George’s County schools created a “newcomer curriculum,” a 12-week course that every student who didn’t speak English and was new to the country would take. The goal was to quickly build an English vocabulary.

Tanya Gan Lim teaches this class to kindergarteners at Cooper Lane Elementary School in Landover Hills. They focus on practical themes, like transportation, the weather and food. But the course is also focused on building confidence. Lim encourages her students to speak. “When they’re in the mainstream classrooms, they feel shy, they don’t want to talk because they don’t want to make mistakes,” says Lim.

Ana, a kindergartener at the same school, is more confident after just two months in the newcomer course, though she still needs practice sounding out certain syllables. (We’re not using her last name to protect her privacy.) She wants to learn English to “be smart” and uses Google Translate to look up words she doesn’t understand. There’s also a more practical reason. At seven years old, she needs to translate for her mother in the grocery store: “If we go to somewhere and my mum says ‘how much?’ and I say is three dollar or four dollar. And she is happy. She say, ‘I love you,’” Ana says.

There are more than 27,000 English learners across Prince George’s County school system in this newcomer curriculum, so the district has also made a big push to support regular classroom teachers. They’re taught strategies like using visual aids and hands on learning.

A classroom in Cooper Lane Elementary School in Landover Hills, Md. Tyrone Turner / WAMU/Dcist

Christian Rhodes, chief of staff to the Prince George’s County Public Schools superintendent, says that the school system prioritizes initiatives for these children that promote equity. They have to consider that minority populations, like English learners and children in poverty, collectively make up the majority of the county’s students. “That is our core base,” he says. “And we make decisions as a school system based off of the population of students we have.”

But Rhodes cautions against assuming that the district has more funding than others to support this population. Instead, he says, the district’s attitude is: “Budget is a function of priority.” It has allowed principals a level of fiscal autonomy so they can fund priorities based on their school’s needs; the district also regularly partners with county agencies and area nonprofits to fill funding gaps.

School districts in Maryland received some additional money for vulnerable students as a “down payment” after the state passed the Blueprint for Maryland’s Future Act this year. But Rhodes says that funding will expire in June 2021 if lawmakers don’t act. (Lawmakers voted to pass the law, but Gov. Larry Hogan vetoed it. They need to revisit it and override the veto for funding to continue after June.)

And Prince George’s county, like school districts across the country, is anticipating “funding shortfalls” and a “significant deficit” for the 2021-2022 academic year. In fact, Rhodes warns that given trends in immigration and the added financial challenges coronavirus posed to schools, “I think every district in the country is going to see a surge next year when it comes to need.”

Principal Karen Woodson is a master at making everyone feel welcome, documented or not. She recently retired from Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary School in Adelphi, a school that has seen dramatic increases in the number of “newcomers,” who now make up 16% of the student body at the school.

Karen Woodson recently retired as principal from Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary School in Adelphi, Maryland. Tyrone Turner / WAMU/Dcist

During a tour of the school before the pandemic closed it in March, Woodson points to the large flags hanging in the atrium, the first thing you see as you enter the school. “They’re going to recognize El Salvador right away. Every country in Central and South America is represented here,” she says. She hopes when children recognize their flag, they know they are welcome. There are also signs posted all over school that say ‘Being Bilingual is my Superpower.’

Front office staff are bilingual and any sign in English is also posted in Spanish — from the school entrance to the trash cans — and the school stocks several Spanish titles in the library. Woodson says these small efforts help all students see there’s no language hierarchy.

Before she retired, Woodson, who is African American and speaks fluent Spanish, beefed up support staff. With the flexibility she had in her budget, the school hired three additional bilingual teacher aides last year. The school also hired a bilingual community liaison who can connect “newcomer” families to outside services and a bilingual counselor who can support teachers, make home visits and meet individually with children who are struggling.

Those meetings now mostly occur over Zoom, as educators try to find ways to translate their in-person supports to online learning.

Woodson warns that even with these supports, none of this is easy on educators. “With the influx [of newcomers], I have to be very honest. Teachers are tired. It’s a lot.” She says she encourages teachers to talk about how they feel and support each other. “But guess what? We’re tired but committed. We will rest but there’s no quitting.”

Cooper Lane Elementary School in Landover Hills, Maryland.

In October 2019, Prince Georges’s educators voluntarily crowded into a community center for a five-hour seminar with an expert from Harvard University.

Dr. Margarita Alegria, chief of the Disparities Research Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital and a psychiatry professor at Harvard Medical School, was helping educators understand how to support first-generation students.

The teachers were hungry for information — roughly 150 people, from security guards to psychologists and kindergarten teachers, had given up a sunny Saturday to join the session.

Berta Romero, a counselor for English learners in Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary School, hears awful stories from her students. One second-grader said her mother had to cover her eyes because people were drowning in a river they were crossing. Another child talked about the journey to the U.S. in a crowded truck, his father having to push him above everyone else just so he could breathe. A mother tearfully recounted how MS-13 gang members molested her daughter on her way to school. Romero says the weight of these experiences is like these children “carrying a big backpack with boulders in it.”

Berta Romero is a counselor for English learners in Mary Harris Mother Jones Elementary School in Adelphi, Maryland. Tyrone Turner / WAMU/Dcist

The trauma continues for many children after they reach the U.S. Under the Trump administration’s family separation policy, children were kept in frigid detention centers where food was inadequate and kids were not given access to basic hygiene. Several children said the adults there threatened them when they broke one of the many rules — no talking, no making friends, no playing.

At the seminar, Alegria explained the “compounded loss” children experienced when they fled their homes. “They lost their familiar language, their customs, their habits, they lost their social networks,” she said. For older youth, Alegria says, social status is very important. She told educators that helping these children make friends has a “super powerful effect.”

For that reason, Prince George’s County is intentionally focusing on investments in mental health resources.

Before the pandemic closed Prince George’s schools in March, social worker Beth Hood organized “circles” to support newcomer students in High Point High School. The school in Beltsville has about 300 newcomers. Their English is very limited, so she spoke in Spanish and explained very basic aspects of U.S. education, from the layout of the building to the role of school nurses to the expectation they come to class every day. But she also encourages them to share their stories about where they came from and what their lives were like before.

“It’s important for them to talk about how they used to tend cows or how they used to make tortillas or how they used to help their grandmother go to the market,” she says. “These are real life day to day strengths and experiences that they bring.”

Social worker Beth Hood has created and shared signs in Spanish and English to encourage students to work on their mental health and ask for help if they need it. She organizes “circles” so undocumented students can share their challenges, make friends and realize they aren’t alone.

Many of these students came to the U.S. as unaccompanied minors and often don’t trust adults. Hood says these circles are also a way for them to make friends with other teens like them, so they don’t feel alone. Coping skills promote healing. In 2014, when there was an influx of unaccompanied minors resettled in Prince George’s county, teachers at High Point High School asked the principal to create a new social worker position instead of hiring another teacher. Last year, the school added another.

Sometimes Hood teaches her students breathing exercises, and other times they discuss how to solve conflicts. In January this year, they worked in groups, listing out factors that help them do well.

By the end of the class, in February, students began joking around while working on the assignment. Hood was visibly delighted. It was a completely different vibe from the start of the school year in August 2019, when they barely spoke to each other and everyone looked terrified. She says her school intentionally creates opportunities for newcomer students to have fun. Last year, the principal organized a holiday lunch just for them, complete with a D.J., because the holidays — and memories of years past with their families — are so hard.

“They all danced and the kids danced with the staff. And it was just pure joy,” Hood said. “It brings that sense of compassion and love and joy into the school building. And we know that every positive experience that immigrant youth have builds resilience and trust.”

But all of that is harder, if not impossible, to sustain during remote learning.

A hallway in Cooper Lane Elementary School in Landover Hills, Maryland. Tyrone Turner / WAMU/Dcist

Teacher Tanya Gan Lim says she worries that her students aren’t hearing English in the hallways or on the playground now that they aren’t in school. Prince George’s County distributed free Chromebooks and mobile wi-fi units, but often these kids and their relatives don’t know how to log on or troubleshoot problems. Psychologists say their days are spent doing tech support or trying to locate kids who aren’t attending classes during the pandemic. And as their families struggle, undocumented students feel an increasing pressure to help provide.

One of Hood’s students, Luis, was 16 when he fled violence in Guatemala almost two years ago and arrived in the U.S. We’re not using his last name to protect his privacy. His first language is Mam, an indigenous language; he spoke little Spanish and no English. Luis now works in a grocery store. “I finish school at 2:30 and then work from 3:30 to 11,” he says. He needs every dollar to repay his coyote who smuggled him into the country, to pay his lawyer, to pay rent. And he sends money home. “Even one dollar here is a lot of money in Guatemala.”

At first, when customers asked Luis something, he wasn’t able to reply. “Then I practice more, practice more, practice more. Now I help them with everything, no problem!” he says. Luis squeezes in homework after work. But, he admits, sometimes it’s hard to wake up.

Hood says most of her newcomer students start off very motivated to do well in school, “but when it comes down to it, their physical body can only sustain that amount of work and studying.”

But it’s clear that undocumented students want to learn and can achieve.

After years of struggles, Nando graduated high school this spring. He had dreams of becoming a doctor, but for now he’s working as a painter. He’s grateful to his teachers who supported him and wish everyone saw him the way they did.

“We are here because we want to improve our lives,” he says. “To have a better life.”

A version of this story was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. It was also supported by the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism.