Patients, Widows, Researchers Still Dealing With Toxic Legacy of Rubbertown Chemicals

Erica Peterson’s month long series reporting on health issues in Rubbertown, Kentucky, for WFPL, Louisville Public Radio, was undertaken as a 2012 National Health Journalism Fellow. Stories in the series include:

Louisville's air program marks successes, but health concerns linger

Air Issues Plague Park DuValle, One of Louisville's Newest Planned Communities

Rubbertown Odor a Nuisance, But is it Illegal? Hard to Tell

Lung, Colon Cancer Rates Higher Near Rubbertown Than Other Louisville Neighborhoods

Riverside Gardens: A Former Resort Community Besieged By Pollution

Interstate Traffic Makes Air Quality in Rubbertown Worse

No End in Sight for Clash Between Residents, Rubbertown Industry

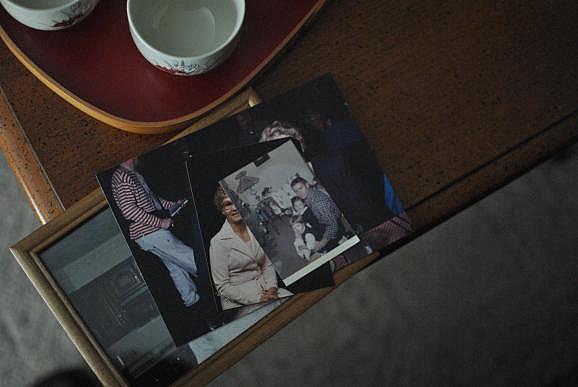

Revis Crecelius, seen here on the day he went to the hospital for surgery.

Seventy years ago, in the early days of Rubbertown, there were a lot of dirty jobs. But no job was dirtier than an entry-level post at the B.F. Goodrich plant. Workers called “poly cleaners” climbed into large vats that had held the chemical vinyl chloride to clean them. And now, decades later, some of these men—they’re all men—have developed serious liver problems. At least 26 of them have developed cancer, and all have died from it.

One of them was Janet Crecelius Johnson’s husband, Revis.

“When he got out of the army, a week later he got a job at B.F. Goodrich. He was just pleased to have a job,” Johnson said.

Revis Crecelius was a poly cleaner for the first year of his 39-year career in Rubbertown.

“No protection. And if he was given any warning, I don’t know it.”

Johnson remembers Revis coming home with his clothes and lunch bucket smelling awful. She shook white powder out of his clothes before she put them through the old-fashioned wringer washer. And even though he eventually moved on to cleaner jobs in the plant, he was diagnosed with liver cancer in 1995 and died five weeks later.

Johnson has a stack of photos of Revis—there’s Revis in the 1960s with their two daughters, Johnson and Revis on a trip to New Zealand, and then one of just Revis, standing in their kitchen, with a small, sad smile on his face.

“That was the day he went to the hospital,” Johnson said.

A rare cancer

By 1975, several cases of cancer had been confirmed among Goodrich’s vinyl chloride workers, and new federal regulations went into place to limit exposure. But the liver problems can lay latent for years, and for the next several decades, former Goodrich workers were continuously diagnosed with liver diseases. Many developed cirrhosis of the liver and fatty liver disease, and 26 died from the rare liver cancer hepatic hemangiosarcoma.

Dr. Matthew Cave and Dr. Craig McClain are professors and researchers at the University of Louisville. They’ve been working to figure out how vinyl chloride affects the liver—and what effect other chemicals could have on the organ.

There are only about 30 cases of hepatic hemangiosarcoma every year worldwide. And McClain said the cancer's rarity allowed scientists to link it to vinyl chloride exposure.

“It’s much harder to show an association between some type of environmental exposure and let’s say colon cancer or breast cancer because they’re relatively common,” he said. “But it’s much easier in showing the link between vinyl chloride and this liver cancer because it’s so rare.”

Credit Erica Peterson / WFPL Photos of Janet and Revis.

Ongoing research into toxins

In McClain and Cave’s lab, dozens of tall double-wide freezers hold thousands of tissue samples from chemical workers. Some come from employees who were exposed to vinyl chloride. Some come from people who worked with other chemicals, and different combinations of chemicals.

The researchers want to figure out how chemicals other than vinyl chloride affect the liver, and if there are harbingers of liver disease in these samples. But McClain said there’s a major hurdle to the research.

“We’ve found that a lot of environmental toxins can cause liver injury without causing major elevation of the liver enzyme,” he said. “So there’s one of the things that Dr. Cave and I are interested in, in finding new markers for toxin-induced liver injury.”

Without elevated liver enzymes, that means a simple blood test won’t reveal any problems. So McClain and Cave want to see what other enzymes in blood can point to liver problems, and determine the safety of the chemicals companies are currently using.

The researchers have tested 25 former Goodrich workers and found fatty liver disease in 21 of them. The link between this malady and exposure to chemicals and toxins isn't as clear, but Cave is studying it.

“One in four to maybe one in three patients people in the U.S. have fatty liver disease,” Cave said. “And it’s typically been associated with overweight, obesity or alcoholism. But are environmental chemical exposures playing a role in this epidemic of fatty liver disease? I’m not sure but that’s a major question in the future that we’re currently studying.”

B.F. Goodrich doesn’t run a factory in Louisville anymore, and companies like Zeon Chemical and Lubrizol have taken over some of the former Goodrich lines. Vinyl chloride is still used in Rubbertown, but it’s much more heavily regulated than it used to be. Since 1975, workers that deal with the chemical are required to wear respirators and undergo medical surveillance, among other things.

A PBS documentary, “Trade Secrets” produced in 2001 looks at vinyl chloride exposure at a Goodrich plant in Texas and shows documentation that the company knew the chemical was dangerous by 1959.

Vinyl chloride in the air

Vinyl chloride is covered under Louisville’s Strategic Toxic Air Reduction program, and companies are required to get permits to emit the chemical. It’s been detected in air monitors in West Louisville for fourteen years—ever since Russ Barnett at the University of Louisville started testing the air for dangerous chemicals. Barnett says 2012 was the first year the chemical didn’t turn up in monitoring—but even that doesn’t mean it’s gone.

“Not seeing it is a good thing,” he said. “But at the same time, our detection limits are not…even though we’re detecting less than a part per billion, it’s still not fine enough for us to find what we consider a safe level for this known human carcinogen. So even by not detecting it, we could still have a risk.”

Though it’s unlikely anyone breathing the air in Louisville would ever be exposed to concentrations of vinyl chloride as high as those the former Goodrich employees were exposed to, the chemical could still pose a risk. And vinyl chloride is suspected—though not confirmed—to have also played a factor in the death of 16 former Goodrich workers from brain cancer.

Cave and McClain praise the collaboration between Zeon and the university—the researchers are involved in ongoing medical monitoring and blood sampling of the plants' workers, in an effort to detect potential problems before they happen.

But it’s too late for the workers who have already died from angiosarcoma or are suffering from liver disease. Janet Crecelius Johnson wonders why B.F. Goodrich couldn’t have erred on the side of caution. Her husband Revis was diagnosed with cancer a year to the day after he retired. He had worked night shifts for nearly 40 years, and was looking forward to spending more time with his family.

“Every time there’s a wedding, every time there’s a baby, you just think, 'I wish he could be here.'”

This story was originally published in WFPL.org on January 16, 2013

Photo Credit: Erica Peterson