Erica Peterson

Environment Reporter

Environment Reporter

I cover the environment, and how it relates to health and energy issues for WFPL, Louisville's public radio station. Before moving to Louisville, I covered environment and state government for West Virginia Public Broadcasting, based in Charleston, W.Va. I have a bachelor degree in psychology from Carleton College and a master's of science in journalism from the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University.

As West Virginia’s foster care system struggles to hire and retain workers amid low pay and overwhelming caseloads, it stresses foster families and keeps kids from getting the attention they need.

A decade after a federal investigation found West Virginia unnecessarily institutionalizes foster kids, our investigation has found the state’s most vulnerable kids are still being left behind.

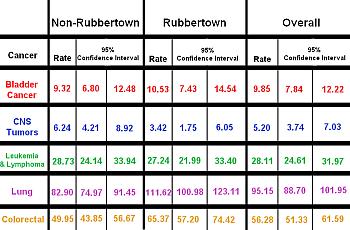

To document Rubbertown, Ky., residents’ claims of unusually high rates of disease, I needed hard data. Originally, I had planned a health survey of the areas around the industrial plants. When that proved impractical, I enlisted a state health monitoring agency.

My series about Rubbertown, Ky., included real people who have lived close by their whole lives and were exposed to all kinds of chemicals in the past. But I would have sensationalized the story if I hadn’t reported the uncertainty that still permeates most of the research on health in the area.

What’s the answer for dealing with past, present and potential safety problems in Rubbertown? Kick out the industry? Move the people? Find some middle ground where everyone can coexist? Is it even possible to coexist?

Start your car. See that puff from the tailpipe in your rear-view mirror? Benzene, butadiene, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide. Louisville communities burdened by pollution on the West End also face emissions from local traffic.

People who grew up in Riverside Gardens tell stories about playing in the landfill—and in some cases, following the bread trucks in and scrounging the day-old bread that was thrown out there.

Louisville, Kentucky's Riverside Gardens neighborhood is surrounded on three sides by pollution. In its heyday, it was a resort community for Louisvillians who wanted a quick, close getaway from the city.

In the early days of Rubbertown, no job was dirtier than an entry-level post at the B.F. Goodrich plant. Workers climbed into large vats that had held the chemical vinyl chloride to clean them. Decades later, at least 26 of these men have developed cancer and died from it.

Everyone in Rubbertown knows someone with cancer. But are people in these neighborhoods actually more likely to get cancer than other Louisville residents? What role has the nearby pollution played?