As post-COVID absenteeism rates fall, high numbers still plague this Paterson school

The story was originally published by Northjersey.com with support from our 2024 Data Fellowship.

District Superintendent Laurie Newell, in an hourlong interview with NorthJersey.com, said earlier this year that no new measures had been put in place to address post-pandemic absenteeism.

Tariq Zehawi/NorthJersey.com

It has taken three years for classroom attendance in the state’s public schools to show signs of recovering after the COVID-19 pandemic hit and absenteeism shot up. Yet evading even this shaky return to normalcy is a K-8 school serving some of the state’s poorest families in Paterson’s 4th Ward.

While the statewide rate of chronic school absences stood at just below 15% in the 2023-24 school year, more than 50% of students at Paterson’s School 6 persistently missed class. School 6 starkly illustrates how urban, impoverished schools must untangle obstinate problems, even as the suburbs move ahead.

Over the long term, chronic absenteeism is correlated to increased high school dropout rates, adverse health outcomes and poverty in adulthood, and an increased likelihood of interacting with the criminal justice system.

Yet despite the staggeringly high absenteeism at School 6, which receives federal Title I aid for low-income districts, the Paterson school district has failed to address the issue with urgency, an investigation by NorthJersey.com revealed.

Story continues below photo gallery.

Through public records requests and interviews, NorthJersey.com found that School 6 fails to comply with critical federal and state requirements designed to improve a school’s connection with parents and reduce absenteeism. Among them:

- School 6 does not have a mandated parent-school compact, a document that Title I schools must have as a way for parents, staff members and students to understand one another’s responsibilities to improve student performance.

- The school does not have any parent engagement letters, as required by law. Such letters are used to inform parents about the school and encourage them to be active participants in their children’s learning.

- School 6, and neighboring Paterson schools 10 and 13 and Eastside High, have no corrective action plans to address absenteeism. The state requires any school with chronic absenteeism above 10% to create them, but the state Department of Education has left it to districts to enforce.

- The district has not hired a parent coordinator to reach out to School 6’s families, despite repeated requests from school officials.

Students are considered chronically absent when they miss 10% of class days or two days a month, including excused and unexcused absences.

While chronic absence rates have dropped nationally and in New Jersey since the pandemic, the problem remains obstinately high in impoverished, urban schools like School 6, where the absenteeism rate remained above 50% for three years beginning with the 2021-22 school year.

“Chronic absenteeism has risen most, in absolute terms, among disadvantaged students — the very groups that suffered the greatest learning losses during the pandemic and can least afford the additional harms of chronic absenteeism,” education expert Nat Malkus of the American Enterprise Institute, a right-leaning Washington think tank, wrote in a June study.

Story continues below chart.

Teachers and staff members at Paterson’s School 6 have some of the most challenging jobs in public education: engaging students in a neighborhood steeped in complex problems, from violence and drugs to large numbers of single-parent families caught in extreme poverty, a key driver of absenteeism. Sixty of Paterson’s 66 shootings in 2023 occurred in the city’s 4th and 5th wards, Paterson Press reported.

And that all weighs on the students. School 6 recently had 22 out-of-school suspensions in just one year, mostly among fifth and sixth graders.

“There is virtually no culture or climate in that school building,” Paterson Board of Education member Corey Teague told NorthJersey.com.

That partly stems from a breakdown of trust between faculty and the principal, Teague said. In June, more than three dozen School 6 teachers submitted a petition to the schools superintendent and the school board asking for leadership changes.

District Superintendent Laurie Newell, in an hourlong interview with NorthJersey.com, said earlier this year that no new measures had been put in place to address post-pandemic absenteeism.

“There is this notion that a new person will bring new things,” said Newell, who was appointed in 2023. “We are continuing what was here before I came."

"It’s a work in progress,” she said.

A central attendance team with “boots on the ground" contacts parents to keep them engaged with school, she said.

Newell said she has not tracked school-level initiatives.

School 6 staff members are in touch with about 200 students who miss school regularly, Althea Melanie Brown, the School 6 principal, told NorthJersey.com. “Some are in the same household. Some students improve, some do not.”

School officials said they provide students incentives for good attendance, such as access to swag rooms, gaming trucks and field trips.

Disruptive atmosphere, bullying can exacerbate absenteeism

Poor classroom discipline and little support for teachers who try to enforce the rules are some of School 6’s obstacles to creating a welcoming and safe space in the already troubled feeder neighborhood, said Lamal Mattiex, a lunch aide at School 6 since 2015.

Mattiex, who has also coached basketball part-time for years at the school, is now in his 40s. He attended School 6 as a child and returned to the area, he said, to support the kids. They affectionately call him Mr. Sweetz. He has watched the school from the inside and the outside, and knows many families in the area.

District Superintendent Laurie Newell, in an hourlong interview with NorthJersey.com, said earlier this year that no new measures had been put in place to address post-pandemic absenteeism.

Tariq Zehawi/NorthJersey.com

Disorderly classrooms discourage children who would otherwise want to be in school, he said — such as the 6-year-old boy who stayed home the day after he was hurt in school, said Emily, his mother, an Ecuadoran immigrant.

Four months after Emily’s son started first grade at School 6, he began coming home with bruises and scratches, she said.

On Jan. 24, he came home with a bruise on his neck. After hesitating, he eventually told his mother that another student had grabbed him in the restroom.

Emily, who said she left Ecuador after an older child was killed in a shooting that her son witnessed, asked to withhold her last name, and her son’s.

“It's hard to get him to say anything about school,” the Spanish-speaking mother of two said from her apartment in the city’s violence-prone 4th Ward.

The day after finding the bruise on her son, Emily visited the school to complain. A school psychologist promised to ask about the incident, she said.

But the school never followed up, Emily said. The next morning, her son complained of a stomachache and stayed home.

Emily said she then approached a homeroom teacher.

Story continues below chart.

“She said that it is just little kids playing around,” Emily said. “But it's unfair, because it’s violent and my child is the victim.”

When NorthJersey.com asked the district about the incident, it said only that it was obligated to protect student privacy and had investigated "in line with our protocols."

In the 2023-24 school year, School 6 reported 14 violent incidents in its annual performance report to the state. Another three incidents each involved weapons, vandalism and substance use. Twenty-two students received out-of-school suspensions. Five were in fifth grade, and 13 were in sixth grade.

The school investigated one bullying complaint that school year. Schools self-report bullying complaints to the state, a system that experts say creates an incentive for under-reporting.

When Emily reported the bruising on her son’s neck, School 6 officials did not tell her she had a right to file a complaint, she said.

“Some kids do need discipline; they need the structure,” said Mattiex. “But what happens to the kid who just wants to learn? They get stuck, or they hate the environment they're in.”

In June, 38 faculty members addressed a petition to Newell, the district superintendent, and sent it to school board members, asking for a change in school leadership.

Public School 6 in the 4th Ward, Paterson, N.J., July 18, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

Teachers, aides and other staffers did not mention Principal Althea Melanie Brown by name, but they requested that Newell replace her with a popular vice principal, Kathia Nieves, for the 2025-26 school year.

Nieves instead was transferred to another school, according to a June 25 agenda item presented to the board. Brown, who is paid about $145,000 annually, has been employed by the district since 1999.

The district did not address the petition to replace Brown at a June board meeting or acknowledge its receipt to NorthJersey.com when contacted with a request for comment. Teague, the school board member, said Newell did not respond to his email about it.

Teague said School 6 was orderly enough when he toured it in the fall. But toward the end of the school year, he heard from employees about Brown’s management style.

Brown allegedly talks down to staff members and students, is defensive and unapproachable, and doles out discipline arbitrarily and unprofessionally, said former gym teacher Gina Desino. Desino resigned on June 25 and is joining another district, she told NorthJersey.com, after 19 years teaching in Paterson.

Public School 6 in the 4th Ward, Paterson, N.J., July 18, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

The district said it takes personnel matters seriously, but would not comment on the criticism of Brown. "We remain focused on fostering a supportive school environment for all students and staff," it said.

Poor culture and teacher morale have long come at the expense of the 4th Ward’s children, Desino said. Teachers who fall out of favor are often transferred to School 6 as “punishment,” she said, a claim supported by others with links to the district and interviewed by NorthJersey.com.

“It's clear from the ground and also from the data — the numbers don’t lie — and the experiences from the community," Teague said. "You put all that together and it shows that this is a very bad situation.”

“A lot of the kids that are staying home from School 6 are kids who are actually very smart,” said Mattiex, the lunch aide. “They don't want to be there. It's too much chaos for them. They don't like it.”

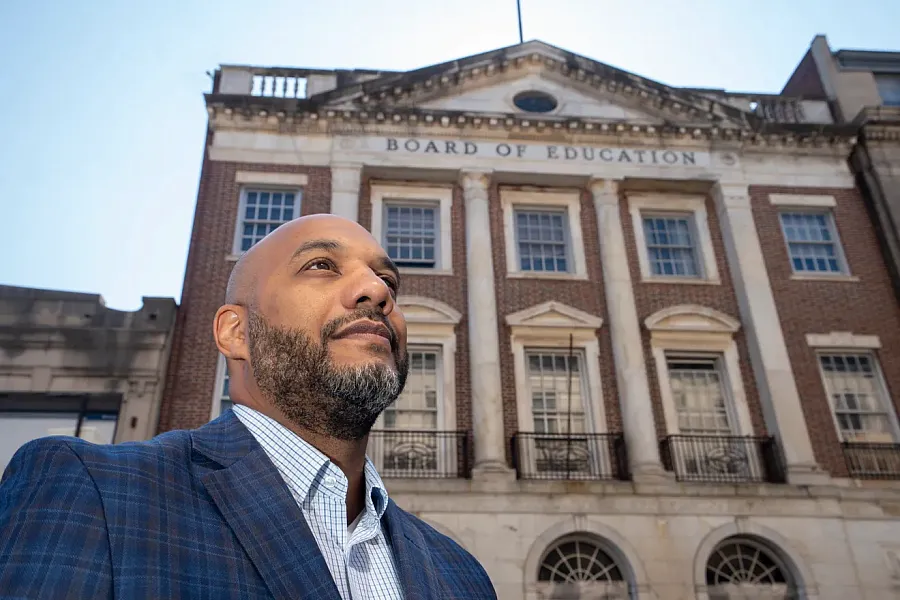

Corey Teague, Board of Education commissioner, stands outside Public School No. 6, also known as Senator Frank Lautenberg School, on Carroll Street in Paterson on Monday, July 28, 2025.

Julian Leshay Guadalupe/NorthJersey.com

The school’s full-service community grant partner, New Destiny Family Success Center, is a Paterson nonprofit with services in the building, Desino said. “So there are options for the school to come up with ways to give these kids incentives to come to school, to wear uniforms, and to behave. The problem is that the administration — other than the transferred vice principal, Dr. Nieves — does not hold these kids or their parents accountable.”

“Vice Principal Nieves told the middle schoolers that if they didn’t wear uniforms they would not get recess,” Desino said. “And they started wearing them.”

Paterson Public Schools declined a request by NorthJersey.com to tour School 6, saying it needed to maintain “a structured learning environment” for younger students. It also declined interview requests with district officials who have overseen attendance and absenteeism since before the pandemic.

Poverty drives absenteeism

Poverty is a key factor driving absenteeism in Paterson’s schools, said T.J. Best, a former Paterson school district director of culture, climate and non-traditional programs. Best was also a state-appointed monitor who oversaw the district’s transition from state to local control in 2020.

The result of that poverty is chronically ill children living in unsanitary conditions, Best said, children who act as caregivers to their siblings, children from families that do not connect with school, immigrant families picking up during the school year and flying home when airfares are cheap, and even “menstrual poverty,” when young girls miss school because they cannot afford pads or tampons.

The other side of that coin is a school’s climate and culture, Best said — good attendance signals trust between a school and its parents.

Best, who attended School 6 growing up, supervised hiring 17 chronic absenteeism specialists in 2018 under Newell’s predecessor, Eileen Shafer, a move to shelve an older system of badge-wearing truancy officers.

T.J. Best, a former Passaic County commissioner, stands outside the former Paterson Board of Education building on Church Street on Monday, July 28, 2025. Best is currently a senior adviser for the New Jersey Public Charter Schools Association.

Julian Leshay Guadalupe/NorthJersey.com

Shafer’s program “tried to make a dent in the problem,” Best said, with a task force targeting absenteeism that produced results within a few months.

Paterson is a Title I district, a federal classification that awards additional funds to impoverished areas where at least 40% of students come from low-income families. The total Title I budget for 2024-25 was $29.8 million, said the board’s latest proposal, but with that funding come legal obligations that the state tracks and districts must follow.

Parent-school compacts

School 6, despite its elevated problems, and despite a framework created by the government to foster parental buy-in, is not in full compliance with state and federal law about how it interacts with parents to create engagement, NorthJersey.com found.

Title I schools serving low-income children are legally bound to draft “parent-school compacts” that outline how parents, staffers and students “will share the responsibility for improved student academic achievement,” according to state guidelines.

That compact is missing for School 6 as a document and as an ideal. Attempts to craft one with support from all parents fizzled out in 2023 due to disinterest among parents, school administrators said in annual planning documents reviewed by NorthJersey.com. “We did complete the parent compact with as many parents as decided to participate. Parents felt the document was too lengthy and opted out,” a school official said in a 2022-23 plan.

Annual parent meetings, contacting parents with letters

The federal government has created a framework for parental buy-in for districts such as Paterson. Title I schools must hold annual parent meetings, regularly contact parents with letters, and inform them of changes to curriculum and staffing. The district refused to let NorthJersey.com observe parent workshops mentioned in School 6’s annual plan for June and October this year.

The district could not identify any parent engagement letters or documentation about efforts to reduce absenteeism in School 6 in response to a public records request by NorthJersey.com.

“Federal law requires schools to engage parents in two-way communication that is meaningful and pertains to learning and other school activities,” said Peg Kinsell, policy director at SPAN Parent Advocacy Network, a Newark-based parent watchdog organization.

Story continues below chart.

“My question is, if you have no parent engagement letters, how are you meeting the requirement?” Kinsell said. “Are you mind reading? Osmosis? Maybe it’s through your school portal, electronically.”

“Where’s the accountability?” she said. “If you don’t know to ask those questions, things don’t change.”

Corrective action plans

State law requires any school with chronic absenteeism above 10% to create corrective action plans, or CAPs, based on parent surveys.

School 6, and neighboring Paterson schools 10 and 13 and Eastside High, have not created a CAP since the 2021-22 school year, according to the results of a public records request by NorthJersey.com.

No CAPs were identified, but some annual school plans “include attendance-related goals,” the district said. School 6 listed reducing absenteeism as a goal in its 2024-25 plan, the records showed.

The state Education Department did not say whether it was aware that School 6 had not created these plans. The state works with schools that are identified as needing help through their annual plans, but CAPs are a local issue, said spokesperson Laura Fredrick.

“Corrective action plans involving chronic absenteeism are a local process, and local school districts must comply with the requirements in state statute and regulation,” she said.

That response bothered Kinsell, of SPAN. “If the law is such that no one will enforce it and there’s no accountability, that’s also a huge problem,” she said.

Poor enforcement of Title I laws designed to engage parents is a common problem. The U.S. Government Accountability Office found “little difference in the ways that parents from Title I and non-Title I schools participate in and receive information from their schools and their overall satisfaction with those schools,” it said in a 2023 study.

Parent coordinator role vacant

School 6's leaders have repeatedly asked the district to hire a parent coordinator to directly engage with students and families, according to its annual plans for the 2021-22 and 2022-23 school years.

That role is still unfilled. The district said it engages current staff members to contact parents instead.

But teachers are already stretched. Adding them to committees or assigning new tasks beyond their duties makes little sense, said Mattiex.

When they are already managing classrooms and bringing students up to speed academically, it is unfair to expect teachers to create parent engagement without a clear plan or extra pay, he said.

Asked for minutes from meetings where attendance was reviewed, the district had none to share.

"Although School 6 holds regularly scheduled meetings of its Attendance Review Committee, no formal minutes are generated as a result of those meetings," the district said.

A change in culture

It is unfair to put the burden entirely on the district, Mattiex said. Parents no longer see teachers as allies in their kids’ education, he said, based on his many years of involvement at the school.

“Teachers can feel like no one has their back,” he said. “So, if you're a teacher — don't tell my kids to take the hood off. Don't tell my kid to sit down. Don't tell my kid to put their phone away.”

Children can have “big chips on their shoulders” from living in a tough neighborhood, Best said, which also leads to disciplinary situations.

"When you're dealing with disciplinary issues, it's normally because of something that happened outside of the school, in their home or neighborhood, that they're bringing into the building," Best said. "As an educator you have to literally spend time to remove those external negative barriers before getting to a point where you're even able to educate the child."

Public School 6 in the 4th Ward, Paterson, N.J., July 18, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

“If I have three 6-year-old boys, you would believe they would all be in the same class on the same level. But they're not,” Mattiex said. “You have to teach them separately on different levels. That's kind of hard when they're in the same classroom, because we only have 45 minutes per period.

"Then you have your disciplinary situations," he said. "Then you must backtrack for kids who are absent. That’s just a lot on a teacher.”

Mattiex’s relationships with neighborhood families has helped him handle disruptive children. One single mother used to call him to come to her home and wake up her son to get him to school, he said.

But the school’s climate and culture put some of the youngest children at a disadvantage, said parent Destiny Williams, 26, who attended School 6 as a child and sends her son to kindergarten there.

“I do as much as I can with my son at home. I read with him, help him with letters,” she said. “But the moment he gets to school, they say he can’t do it, he can’t read,” she said.

“One day he told me they weren’t really helping him,” Williams said. “So, I’m like, what’s going on? I’m doing my part at home, but his teachers keep saying he’s not learning."

Less than 10% of School 6 students met expectations in state tests of math and English in 2023-24, state data showed. A rapport with families was critical to the success of Paterson's better-performing charter schools, said Best, who now heads the Paterson Charter Round Table, a collective of local charters.

“At least five out of the seven charter schools have half days every day of the week where they have professional development or are contacting parents,” Best said. “And that is huge. If I’m a homeroom teacher, once a week, contacting all the parents in my class is part of my job.” The charters have a longer school year to accommodate those half days.

School 6's radius of concentrated poverty

But charters serve more stable populations, Best said, from different neighborhoods and different income levels, unlike a public school that is limited to a single ZIP code — in School 6’s case, an impoverished ZIP code.

Poverty is the biggest driver of chronic absenteeism, said a 2018 study by the nonprofit Attendance Works. It is “magnified and compounded” in the 4th Ward section that is served by School 6, said Newell, the superintendent, further weakening family engagement.

The median per capita income of adults living close to the school is $18,000, according to U.S. census tract data. Almost all homes are rented, and the population is transient.

For all its problems, the four-block perimeter around the school is “really not that bad of a neighborhood,” said Desino, the gym teacher who resigned from the district. “I used to walk around every lunch going to the local stores and say hi to the community. If you show them respect, they’re going to respect you.”

Still, there is far less confidence in the district’s schools now, compared with when they were growing up, said many parents NorthJersey.com interviewed throughout the 4th Ward. Most preferred charter schools to public schools for their children.

Hamilton Avenue near Public School 6 in the 4th Ward, Paterson, N.J., July 18, 2025.

Anne-Marie Caruso/NorthJersey.com

The 4th Ward’s Black families are “multigenerational,” Best said.

Mothers and grandmothers used to have an eye on all the kids when he was growing up, Mattiex said. Those bonds among the 4th Ward’s Black residents have diluted, he said.

Parents look for solutions

A crowd of cheerful children tumbled onto the Carroll Street sidewalk at dismissal on a Friday in April as School 6’s tall gray doors opened beneath a stately but worn 1921 façade.

There were no staff members present when a tall boy grinned playfully and swore as he pushed a much younger girl down to the ground. The child looked up at him gamely, and tried to stand, but was pushed again.

Children circled around for a few minutes until a school aide with a walkie-talkie showed up and dispersed the students. “They’re play-fighting,” he told a reporter who observed the incident. A little later, Brown, the school principal, appeared outside the school, directing foot traffic.

“This school is rough,” said Williams, the mother who was walking her kindergartner home. “First grade, I don’t want him to be there," she said.

Williams wasn’t sure how she would find a better local school, but she knows the area well. It is her home.

It was more of a hurdle for Emily, the Ecuadoran mother, and her husband, Ronny. “I don’t have the money to move to another town,” Ronny said.

Still, school staff members had been more communicative with her after NorthJersey.com asked about her son’s bruise.

“In addition to letting me know when things happen to my child, they have been a little more attentive,” she said.

The family transferred their son to a different elementary school in May. “My son is fine for now,” Emily said.

A school employee privately told Emily that their neighborhood is unsafe in the summers because of an uptick in shootings. “There are drug dealers working near where we rent along 12th Avenue,” Ronny said.

“I’m afraid for my son,” Emily said. “I don’t want him to witness more violence.”