Private Physicians Drive Up Antibiotic Resistance, Helped Along By Patients

Physicians who see patients outside of hospital systems, such as those working in private offices, contribute disproportionately to the spread of antibiotic resistance because they are more likely to prescribe drugs unnecessarily, a first-of-it-kind nationwide study that looked at patterns of antibiotic use and drug-resistant infections has found.

Physicians who see patients outside of hospital systems, such as those working in private offices, contribute disproportionately to the spread of antibiotic resistance because they are more likely to prescribe drugs unnecessarily, a first-of-its-kind nationwide study that looked at patterns of antibiotic use and drug-resistant infections has found.

A number of factors influenced the tendency to overprescribe, including mostly patient demand, but also time pressure to end patient visits sooner, fear of malpractice lawsuits if a prescription is denied, the use by some health plans of “patient satisfaction” surveys in contracting with physicians, and the way doctors are compensated for their services.

“The average patient suffering from a cold or an ear infection wants immediate relief and sees a prescription for antibiotics as the ticket for recovery, and the physician may be only too happy to oblige if writing it benefits her practice,” says the report, published online in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases.

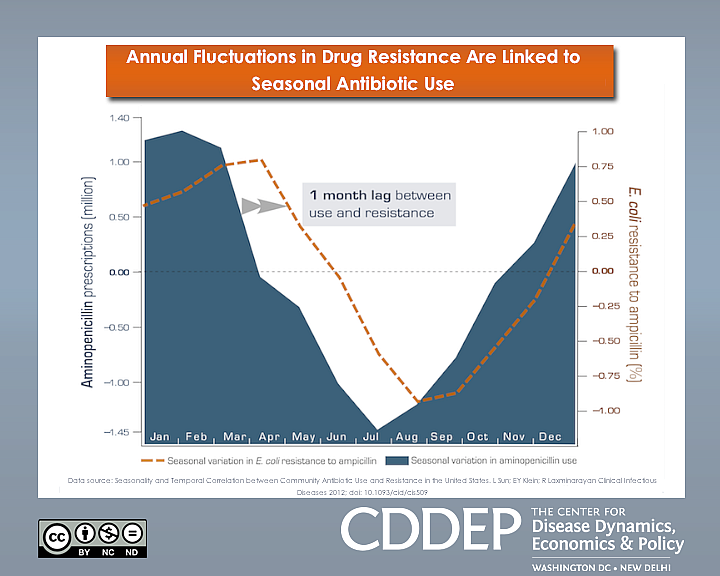

The study found that the occurrence of difficult-to-treat infections in U.S. hospitals mirrored the rate of antibiotic prescribing in communities served by those hospitals, generally rising during flu season and subsiding in the spring and summer months. To illustrate the link, the researchers mapped the results of a 10-year analysis of the data showing an average lag of one month between antibiotic use and parallel surges and declines in ampicillin-resistant Escherichia coli.

Ampicillin is widely used to treat pneumonia, bronchitis, ear and skin infections, as well as E.coli and Salmonella from food poisoning. It is not effective against viral infections such as the flu and the common cold, but along with other antibiotics doctors frequently prescribe it to treat such complaints — often because of patient expectations.

“People should be aware that when they demand antibiotics when they don’t need them, it has an effect on other people who actually do need them,” said study author Eili Klein, a mathematical biologist at Princeton University. “So if you were to have a major procedure in a hospital during the winter, the chance that you would get an infection that’s hard to treat with antibiotics is greater.”

Among the report’s most startling statistics is the fact that in 1987 only 2 percent of patients infected with Staphylococcus aureus, a common pathogen, failed to respond to methicillin, but by 2004 more than 50 percent did. In recent years, methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), which causes a variety of diseases from skin infection to septic shock, has also become resistant to vancomycin, a potent drug considered the antibiotic of “last resort.”

Earlier this year, the American Society for Microbiology published the genome of vancomycin-resistant S. aureus (VRSA) in an effort to understand and thwart the mechanisms that enable the bacteria to develop total resistance.

“One of the key points that comes out of this is that patterns of [antibiotic] prescribing have real adverse effects on the hospital system. Doctors prescribing antibiotics often do so without thinking how that affects the community,” said Klein.

He noted that hospitals have made a great effort to reduce the rate at which prescriptions are given, but that most of that work “is not filtering down to the community.” As a result, frequent use of antibiotics during the winter increases the likelihood of hard-to-treat infections, and even though resistance eventually subsides when prescriptions taper, it does not go down to the same level.

Consumers can get infected with MRSA during a hospital stay, from skin-to-skin contact, and by handling or eating meat contaminated with the bacteria. Such meat is usually sourced to animals fed an excessive amount of antibiotics for growth promotion, and some companies and consumers are calling for federal restrictions on agricultural use of the drugs.

The researchers associated increases in multidrug-resistant MRSA in the hospital with excessive use of two specific classes of antibiotics often prescribed to treat pneumonia (fluoroquinolones) and offered as a substitute for patients allergic to penicillin (macrolides).

“Patients and doctors should work together to reduce the number of unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions by not taking or prescribing antibiotics to treat viral illness, such as colds and flus,” said in a statement Ramanan Laxminarayan, the lead author of the study. He noted previous research showing that up to one million antibiotic prescriptions each year are given out when not needed.

Laxminarayan emphasized the importance of seasonal flu vaccines as a preventive measure against both illness and unnecessary prescribing and consumption of antibiotics.

Community-acquired antibiotic resistance becomes a problem when patients who use antibiotics frequently for mild illnesses require therapy for more serious conditions, such as infections that develop as a result of surgery or cancer-related complications. It affects the general population by introducing into the environment evolved germs such as MRSA and VRSA, also known as “superbugs.”

“The cost of [antibiotic] consumption, aside from the price of the drug itself, is borne by future generations, who because of resistance will have fewer options for treating infectious diseases,” the study states.

In the U.S., more than 63,000 patients die every year from hospital-acquired infections that are resistant to at least one antibiotic. The economic costs are staggering: in 2004, the Pennsylvania Health Care Cost Containment Commission estimated that Medicare was billed at least $20 billion for the treatment of hospital-acquired infections.

The study found that even in moderate cases, patients have to be given a higher dose of drugs in order for the treatment to be effective. For example, as of 2002 the annual national cost for treating ear infections had risen by an estimated 20 percent, or $216 million.

But the spread of antibiotic resistance is not only the fault of demanding patients and obliging or irresponsible physicians. They can share the blame with insurance companies that price their individual policies out of reach for most uninsured Americans, but continue to reimburse patients for antibiotic treatment regardless of whether it is warranted. Klein says pharmaceutical firms that benefit from antibiotic sales and thus have few incentives to manage the problem also contribute.

“Who’s ultimately responsible is very difficult to determine in our health care system, but that allows for a great role for health policy makers to play.”

The report is part of a project by the non-profit Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy to evaluate the growing problem of antibiotic resistance in the U.S and propose public policy responses. It is the result of contributions by researchers at Resources for the Future, the University of Chicago, the National Institutes of Health, and Emory University, and was funded in part by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

(This article was published first on Forbes.com on July 9, 2012.)