Public housing authorities fail to test all rentals for radon, leaving tenants at risk

The article was originally published in The Columbus Dispatch with support from our 2025 National Fellowship and Dennis A. Hunt Fund.

Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority headquarters is located at 880 E. 11th Ave., in Columbus' Linden neighborhood.

Danae King/Columbus Dispatch

Hundreds of thousands of Ohioans rely on public housing to keep them from becoming homeless — yet as Marlene Carey discovered, the agencies meant to provide refuge don't always share the full story with their tenants.

Carey felt relieved when she moved into a renovated Northeast Side townhome owned by the Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority in late 2018. She and her two children, Mar'Saunah and Selvion, had few other options.

But, Carey didn't know a little more than year earlier her safe haven was remediated for radon: an invisible, radioactive gas that creeps into homes usually unnoticed. And CMHA didn't perform a follow up radon test to make sure it had successfully mitigated the gas until Carey and her kids had lived there for more than two years, she said.

“They don’t care,” Carey, 35, told The Dispatch. "Why would they think that’s OK?"

While Ohio has required home sellers to notify potential buyers of previous radon testing since 1993, the state fails to mandate landlords tell tenants like Carey if tests have ever found dangerous levels of the gas in their rental, a Dispatch investigation has found.

At the same time, housing authorities across Ohio — including CMHA — fail to test every unit they own for radon, leaving tenants vulnerable to an invisible killer that's been found at dangerous levels in each of the state's 88 counties.

Known as the leading cause of lung cancer among nonsmokers, radon kills an estimated 21,000 Americans a year and has been linked to other serious health issues, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Radon failures have left renters at risk of the gas' deadly consequences and they likely don't even know it, said Jane Malone, national policy director for the nonprofit Indoor Environments Association.

“Tenants are at an incredible disadvantage because they don't own the building,” Malone said. “A tenant is so much more vulnerable and helpless because they don’t even have the means to protect themselves.”

In total, more than 400,000 people in Ohio rely on federal rental assistance to afford housing, according to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a Washington, DC-based nonpartisan research institute. Most federal rental assistance is routed through public housing agencies, such as CMHA.

CMHA officials told The Dispatch they typically only test units during renovations and do not test new properties the agency acquires. Public records obtained by The Dispatch show radon testing was performed in fewer than 2,000 of the more than 6,000 units CMHA has owned since 1995.

Likewise, records obtained from housing authorities around the state show inconsistent testing.

The Lucas Metropolitan Housing Authority in Toledo, for example, manages 2,633 units but had no records of radon testing on file dating back to at least 1995. The only records on file with the Akron Metropolitan Housing Authority showed just nine of the agency's more than 4,000 units were tested for radon in the last 30 years.

The Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority has tested 12 properties since 2016, including four that were each retested, public records obtained by The Dispatch show. The agency owns and manages more than 5,300 units and administers Section 8 Housing Choice Vouchers to more than 11,600 households.

Ohio law requires landlords to maintain their properties in "fit and habitable" and "safe and sanitary" conditions, said Marcus Roth, spokesman for the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio (COHHIO). That law, he said, should apply as much to radon as it does to mold, bedbugs and more.

Although no level of radon is considered safe, the Environmental Protection Agency's recommended remediation level is 4 picocuries per liter.

Public records obtained by The Dispatch show CMHA tested Carey's unit at Ohio Townhouses on June 5, 2017, and found a level of 5.2 picocuries per liter.

Ohio Townhouse located on Brentnell Avenue on Columbus' Northeast Side, owned by the Columbus Metropolitan Housing Authority. In 2017, one unit there tested at 5.2 picocuries per liter for radon, above the EPA's recommended action level of 4.

Samantha Madar/Columbus Dispatch

While CMHA told The Dispatch it installed a mitigation system, records show the agency didn't conduct a follow up test to ensure it was working until nearly four years later on March 29, 2021. Carey had been living there since late 2018.

The follow-up test in Carey's home returned results of 0.3 picocuries per liter. It's recommended a radon test be conducted immediately after a system is installed to check that it's working and then every two years after that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The tests in 2017 and 2021 were conducted as part of a renovation process, said Mike Wagner, vice president of construction at the housing agency. Though most renovations are typically finished in 18 months, the townhouses were part of a larger project that took almost four years to fully complete.

A Dispatch review of records found 18 units at the CMHA-owned Ohio Townhouses, Glenview Estates and Eastmoor Square that had a gap of three years and nine months between initial radon testing and post-mitigation testing.

When asked about records showing CMHA didn't retest Carey’s unit and others right away to make sure mitigation systems were working, Wagner called the lag time unusual and concerning and suggested it might be an anomaly or a "typo." A CMHA spokesperson said he believed the units were empty until they were retested for radon in 2021 but also later said via email that tenants may have lived there during some of that time.

“Our clients are the number one concern,” Wagner said. “We’re concerned about their health, their safety. It is a priority for us.”

'Silently dying': How radon is invading Section 8 housing

Tamika Blue never knew she might be living with a killer.

Blue, 47, of Franklinton, is a Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher holder. The program, managed locally by CMHA and funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, helps more than 13,000 central Ohioans pay for a place to live.

Tamika Blue had her Franklinton home tested for radon as part of The Dispatch's grant-funded testing program that checked nearly 70 homes across the region. Her home tested at 3.8 picocuries per liter for radon, meaning for every liter of air in her unit there were 3.8 radioactive particles floating around.

Samantha Madar/Columbus Dispatch

While the program is a critical lifeline to many, properties that accept vouchers are not required to test for radon.

Blue was part of The Dispatch's grant-funded testing program that checked nearly 70 homes across the region. Her home tested at 3.8 picocuries per liter for radon, meaning for every liter of air in her unit there were 3.8 radioactive particles floating around.

The results were just shy of the EPA's action level, though radon professionals typically recommend retesting when a home tests that close to the threshold.

“You could be sitting there silently dying... and not even know it," Blue said. "That’s scary. You don’t know there’s danger."

When asked about whether landlords who accept vouchers need to test for radon, CMHA officials told The Dispatch that testing for the gas is outside the parameters of its duties in managing the Section 8 program locally.

Since 1993, Ohio has mandated home sellers to notify potential buyers of known radon levels due to previous tests. Landlords, however, are not required to make similar disclosures to renters.

Some local governments have taken their own action. But Malone said it isn't on the radar for most, especially because many housing and zoning codes were written decades ago and are rarely updated. Columbus is in the midst of its own zoning overhaul as the city prepares for an expected influx in new residents in the coming years.

Both Iowa City, Iowa, and Montgomery County, Maryland, require rental properties be tested for radon by a state-licensed inspector and must be mitigated if above the EPA action level. Iowa City also requires units to be retested every four to eight years to ensure systems are working.

"The tenant advocacy world is just overwhelmed with a lot of other... more fundamental and immediate problems like dangerous conditions in buildings and the whole business of the cost of rent," Malone said.

While Blue is worried about being kicked out, she said she planned to ask her landlord to retest and possibly mitigate her home for what she described as the "predator" of radon. Six states offer funding to help remediate homes for radon, but Ohio is not one of them.

If Blue's landlord refuses to mitigate, she said she might move. In the meantime, Blue may be forced to keep living with the invisible killer as Ohio offers no specific protections for renters who want to break a lease due to radon, as Colorado and Illinois both do.

"It’s important to know how these things are affecting your health,” Blue said. “I want to know that I have my children somewhere safe.”

Why isn't more public housing money going toward radon?

A lack of funding has long served as an excuse for HUD and housing authorities to avoid testing for radon, Malone told The Dispatch.

There's a perception that housing agencies already don't have the money for repairs, Malone said. Adding required radon testing, Malone said, would be seen as just another financial burden.

In Columbus, CMHA was estimated to bring in $966 million in 2025 and spend $963.8 million, according to a draft of its 2026 budget. The agency, which is funded through a series of HUD grants, municipal bonds, rental income and other partnerships, estimates its revenue will climb to more than $1 billion in 2026.

Although the Trump administration has proposed sizable funding cuts, HUD had a budget of more than $72 billion in 2025. The federal agency's budget included $417 million to remove health hazards from homes for vulnerable families.

The latest policy on radon, released in 2024 under then-HUD Secretary Marcia Fudge, didn't mandate testing but stated radon must be considered during a housing project's environmental review. Experts told The Dispatch both federal policy and state law would protect more Ohioans if they reflected rules for other known toxins, such as lead-based paint.

For lead paint, HUD requires prospective tenants be given informational pamphlets, a history of lead-based paint and abatement records or reports regarding lead based paint in a rental unit. None of that is required when it comes to radon and renting.

“Across the country, there is a pressing need for stronger policy approaches to reducing radon risks for people who live in rental housing,” said Amy Reed, senior attorney at the Environmental Law Institute. “In many states, radon regulation does not fall squarely within the purview of any one agency, so it can fall through the cracks."

HUD does sometimes give out grants to help housing authorities test and mitigate for radon. In 2024, HUD awarded more than $3 million to agencies across the country, including $600,000 to the Columbiana Metropolitan Housing Authority in Ohio, according to a press release.

Although CMHA typically tests for radon when it's renovating a complex or building new apartments, it cannot afford to test or mitigate every facility it buys. Doing so would "price us out of the market," Wagner said.

That means communities purchased by CMHA last year, such as the Residences at Eden Park on the Northeast Side and the Orchards in Lockbourne, may have never been tested for radon.

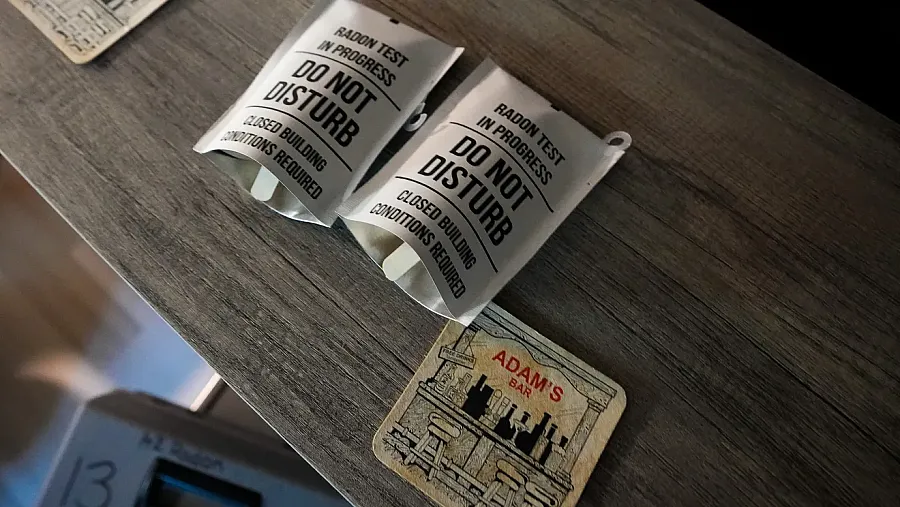

What does radon testing look like? See Ohio residents' experience. An A-Z Solutions technician tests for radon in Columbus area homes, searching for the invisible gas tied to health risks.

VIEW GALLERY

"If nobody else is doing it (and) our competitors aren't doing it that are going after the same properties then it makes it hard for us to do it," Wagner said.

But, officials at the taxpayer funded agency told The Dispatch they actually spend more per radon mitigation system than is necessary.

A standard mitigation system runs anywhere from $1,000 to $2,500 per home and typically includes a pipe and a fan affixed to the outside wall of a home or apartment. The fan sucks radon out from beneath the home and ventilates it outside.

Wagner said CMHA doesn't like how those systems look though, so it usually spends closer to $5,000 or $6,000 to hide the system through a unit's interior walls. CMHA declined to answer questions about how many mitigation systems it has installed in all of its buildings as of this year.

“We hate that look... We don’t want to do it that way,” Wagner said. “To me, (we're) doing it the right way."

What grade does CMHA get on radon?

When it comes to protecting tenants from radon, CMHA's Wagner said the agency does an "A+ job." But other housing agencies have taken more of a leading role when it comes to radon.

Portland, Oregon’s public housing authority, for example, has required radon testing and mitigation in all of its 100 properties since 2017. CMHA has no such policy.

CMHA did not answer The Dispatch's questions about how often it retests units to make sure mitigation systems are working. Documents obtained through a public records request did not show testing every two years as recommended by the CDC.

Testing should simply be mandatory for all rental properties, said Patricia Kidd, executive director of the Fair Housing Resource Center, a Painesville, Ohio-based nonprofit that promotes equal housing opportunities.

“Anything to make an environment safer for families to live in,” Kidd said. “There is so little information out there and so little public awareness of it.”

When it comes to informing tenants about radon in their rentals, Malone said there's a lot of room to do more.

Tenants should have a right to a home safe from environmental hazards and they should be informed if any were ever found in their rental so they can make an informed decision about where they live, experts told The Dispatch. But, Malone described tenants rights as an evolving issue that is "poorly understood" by renters and landlords alike.

Unless local or state lawmakers act, Malone said tenants such as Carey may never get all the details about the homes they're renting. Illinois, Colorado and Maine already each require landlords disclose radon test results to tenants, according to the Environmental Law Institute.

Although Carey no longer lives in CMHA housing, she wishes the agency had been more transparent and upfront from the start.

More than two years after she moved into a townhouse, a test confirmed the radon mitigation system was working. But Carey said that if she had known CMHA hadn’t checked the system before her move-in, she would have asked the agency to do so and may have tried to find another place to stay temporarily.

After all, Carey said, if the mitigation system hadn’t been working the whole time, the impact wouldn’t have been limited to her health — it would have affected her 5-year-old and 6-year-old kids as well.

"CMHA should’ve handled that before tenants moved in," she said. "It can cause health effects down the line. I've got to be dealing with that at the end of the day.”