'Punched in the gut': Uncovering the horrors of boarding schools

Mary Annette Pember wrote this article, originally published by Indian Country Today Media Network, as a 2014 National Health Journalism Fellow, with support from The Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism. Other stories in her project series can be found here:

Truth and Reconciliation: The road to healing is lond and arduous

'Cultural genocide,' Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls residential schools

6,000 kids died in residential schools: Canada Truth and Reconciliation Commission

When will U.S. apologize for boarding school genocide?

Trauma may be woven into DNA of Native Americans

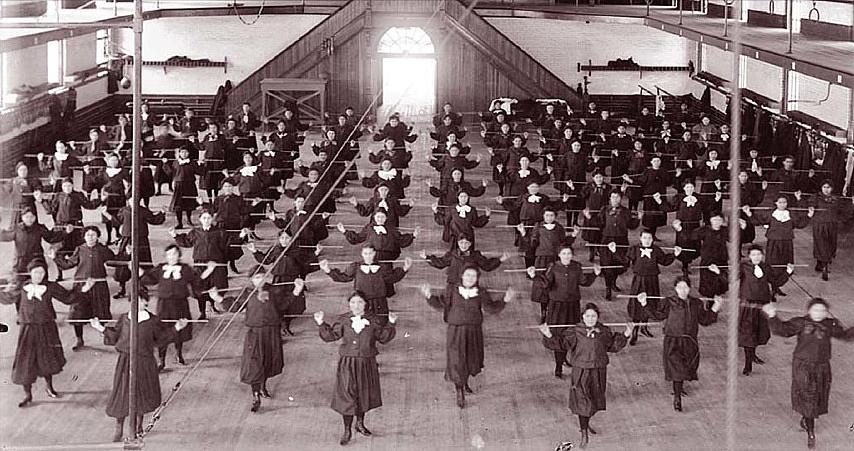

NAA INV 06828200. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution American Indian girls in school uniforms exercising inside gymnasium in 1879 at Carlisle Indian Industrial School.

“No one has ever asked me before,” the elder explained.

“She was answering my question about why she had never told anyone about the abuse she suffered at Indian boarding school,” recalls Denise Lajimodiere, professor of Education at North Dakota State University in Fargo.

Lajimodiere, who also serves as president of the Boarding School Healing Coalition, found that the other survivors she interviewed told her the same thing. “Most of them had never even told their families,’ she says of interviewees who often whispered when sharing details of the sexual abuse they experienced at the schools.

Lajimodiere, a member of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa tribe, is working on a book containing ten of the most powerful survivor stories she’s collected over the past few years. “I don’t want the book to be academic; I want it to be their voices telling their stories.”

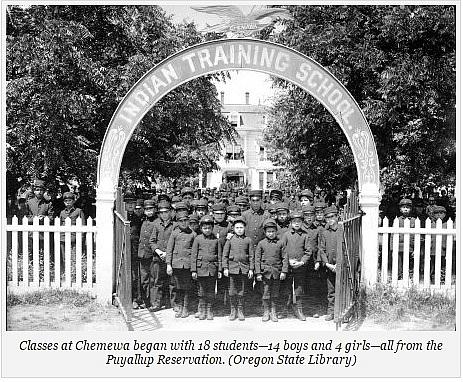

Her journey into the world of boarding schools and the unresolved trauma associated with them began as a means to reconcile with her father, who attended Chemawa boarding school in Oregon. “I wanted to figure out my Dad’s violence and find a way to forgive him,” she says.

After seeing an advertisement that the Boarding School Healing Project, an organization that predated the Coalition, wanted researchers, she applied and began interviewing survivors in North Dakota. “I went all over the state, conducting the interviews in keeping with traditional ways as much as I could. Afterwards, I’d go outside and sit in my car and cry.”

Lajimodiere says her research about responses to unresolved trauma and hearing the stories of survivors helped her understand her parents, their harshness and lack of affection. (Her mother attended boarding school in Wahpeton.) “They weren’t parented, they were just beaten.

“When I read that unresolved grieving is mourning that has not been completed, with the ensuing depressions being absorbed by children from birth onward, I felt like I had been punched in the gut. Years ago I had come across the term ‘adult child of an alcoholic,’ and was shocked to realize that it defined me. Once again, upon hearing the terms and seeing the definitions of generational trauma and unresolved grieving, I thought, “My god that is me; it is my family, my brother, my sister, aunts, uncles, grandparents,” she wrote in the essay “A Healing Journey,” published in the Wicazo Sa Review.

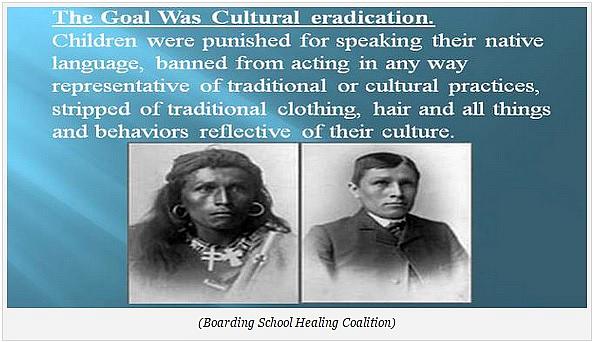

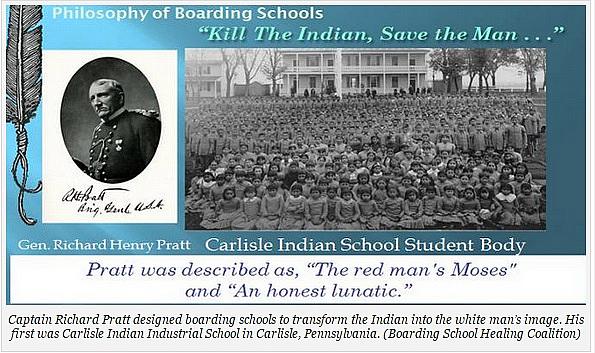

Lajimodiere recalls an incident with her father after she began researching the boarding school experience. “One day, about a year before he died, I brought the documentaryIn the White Man’s Imagefor my father to watch. The video spoke of the government’s attempt to stamp out American Indian culture, language, tradition, stories, and ceremonies. It reviewed the background of Captain Richard Pratt and detailed his educational experiment designed to transform the Indian into the white man’s image. Pratt’s first school, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, was profiled, and the second school, in Chemawa, near Salem, Oregon, where my father was sent, was mentioned. The video documented the use of whistles, bells, bugles, and military-style punishment and daily regiment, the building of guard houses on school campuses, kids dying of homesickness, disease, and poor nutrition. The narrator said that boarding schools left a legacy of confused and lonely children.

She learned that her father nearly died from a beating at Chemawa and that her mother was routinely locked in a closet during her boarding school days.

Learning about her parents experiences and hearing their stories has helped her and her family. “I had to forgive my parents after I understood what happened to them.”

She hopes her work will lead others to understanding, forgiveness and ultimately healing. “Before reconciling with the U.S government, we need to reconcile among ourselves first,” she says, adding that Native peoples need to create their own means to address internalized racism and the impact of historical trauma. “No one can do it for us; we have to do it for ourselves.”

She argues that the government has a legal and moral obligation to support those efforts. “My hope is to see monies flood in from the U.S. government in support of healing that is specific to historical trauma especially relating to boarding schools. We need counselors who are trained in the history of boarding schools, the losses or heritage, land and family.”

She hopes to see a time when survivors and their families can have access to a safe place in which to tell their stories. “Documenting survivors stories helps create connective tissue between what happened to them and what is happening in Indian country today. Allowing them to tell their stories also provides a platform to demonstrate the courage and resilience of Native peoples.”

Lajimodiere continues her work with the Coalition, which includes documenting survivor stories, but often finds it emotionally exhausting. “I have to take mini-breaks and care for my own psyche,” she says.

For instance, she recently received her mother’s records from Wahpeton but has not yet been able to open the envelope. “I know I will when I am ready,” she says.