How a federal foster care law is failing its promise to keep families together

This article was originally published in AfroLA as with support from our 2025 California Health Equity Fellowship.

Edwina Thomas is the program manager for Young Visionaries, which teaches a culturally-specific parenting course for Black families. Despite being rubber stamped by the federal government as an effective tool, these programs have struggled to get federal funding.

(William Jenkins/AfroLA)

Edwina Thomas loves helping parents talk about raising their kids.

One evening this summer, she led a discussion with half a dozen parents about what to do when kids drink and do drugs at home, part of a 7-week class that meets twice a week.

“When I was in high school, I had friends whose parents preferred that their kids did whatever they were doing in their house,” said the lone father in attendance, one of seven parents gathered in a conference room at Young Visionaries, a youth development center in San Bernardino. “Their mindset was, ‘At least I can see them. I know how much drinking they’re doing.’”

One mom agreed. “I would rather them do it at home, because I would be scared for them to do it elsewhere,” she said.

After some more back and forth, Thomas chimed in.

“Family rules, they are like a coin. There’s a ‘do’ side and a ‘don’t’ side,” she said, adding that it’s up to parents to define which behaviors are which and make sure their children learn to respect them.

The Effective Black Parenting handbook is a guide for Black parents.

(Elizabeth Moss/AfroLA)

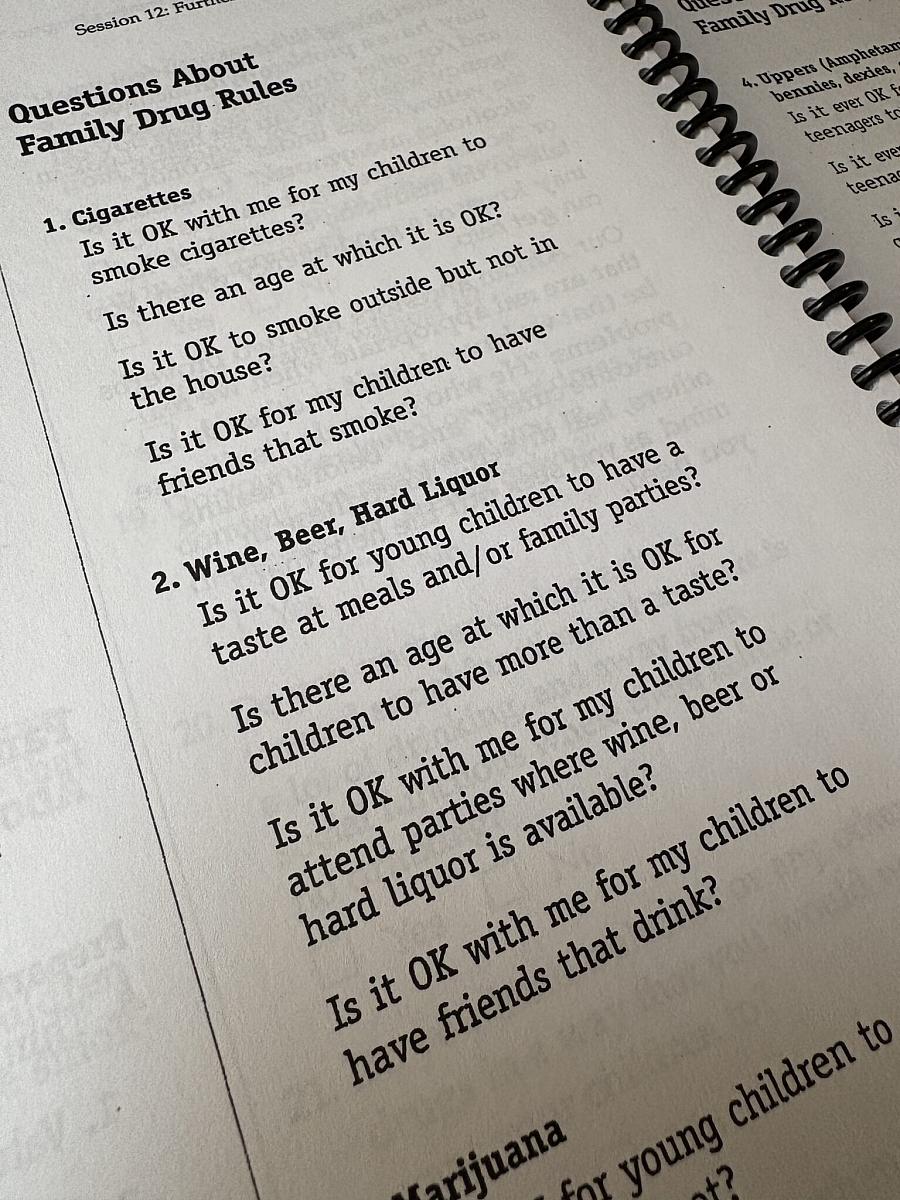

As part of the Effective Black Parenting program, parents are asked questions that help them establish family rules around drug use.

(Elizabeth Moss/AfroLA)

Conversations like this are the bedrock of Thomas’s parenting class. The class is called “Healthy Perspectives,” but it’s guided by a curriculum created 40 years ago called “Effective Black Parenting.” The class is designed as a parenting framework for Black families. Instead of spanking their kids when they don’t follow the rules, parents are taught to help kids understand why the rules exist in the first place, for instance. Thomas teaches parents to engage with their kids outside of discipline, such as offering praise, or making time for idle chitchat.

“Parenting isn’t the same across the board,” Thomas said. “In our community, we want to relearn how to discipline our kids, and that is a really serious, important topic of conversation.”

The program was developed in Los Angeles, and is used by organizations across California. The state has doled out grants to implement it in schools and at community-based organizations. At one point, it was acknowledged by the Clinton Administration.

Effective Black Parenting has also been rubber stamped by the federal government. The U.S. Administration for Children and Families (ACF), which funds and manages the country’s foster care programs, has bestowed its approval on the program, unlocking special federal dollars in the process. This money could cover half the cost of administering the program for organizations like the one Thomas works at, in perpetuity.

But instead of money raining down on these organizations, a labyrinth of administrative obstacles created by the state and federal government has made the money tough to get.

As neutral as this class sounds, it’s a program not without controversy – some critics say that insinuating there is a “right” way to be a Black parent is misguided. But proponents like Thomas, who works in a youth correctional facility once a week, believe it can transform families and save kids from getting in trouble with the law.

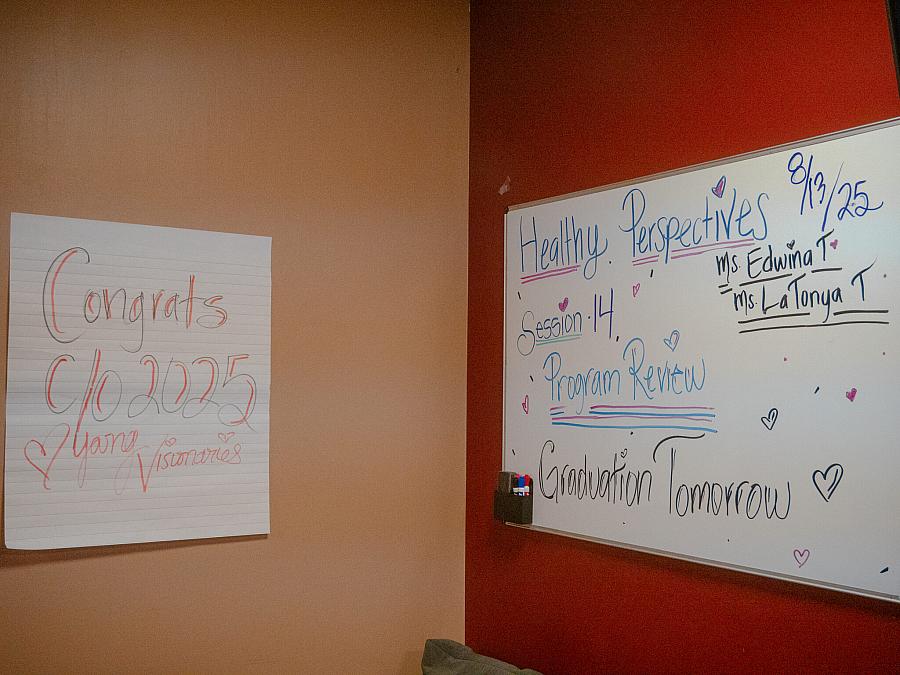

Inside the Young Visionaries office in San Bernardino, a dry erase board details the name and instructors for a parenting course and celebrates an impending graduation.

(William Jenkins/AfroLA)

Federal dollars aim to prevent foster care

Approval from the ACF isn’t just for show – the agency gives ratings to programs it believes can prevent behaviors that result in children being removed from their homes, such as child abuse. An official rating from ACF can make or break a program’s ability to receive funding from the federal government and private donors. In particular, programs that are rated by the agency are eligible to receive a constant flow of money from a federal program signed into law in 2018, the Family First Prevention Services Act.

It took years to pass, but the Family First law transformed child welfare by giving hundreds of millions of dollars to states to invest in programs that prevent children from being removed from their families.

But after seven years, few programs have been approved by the agency, and even fewer ones tailored to Black families. Out of 95 approved programs, Effective Black Parenting is one of a handful designed specifically for parents of color.

“The programs that are culturally specific are being excluded,” said Sean Hughes, a consultant who is helping California counties implement the law.

This summer, after the Young Visionaries parenting class in San Bernardino is finished, the group of parents play a round of ‘R&B Bingo’.

(William Jenkins/AfroLA)

ACF employs strict standards and guidelines for programs that are seeking approval. Program administrators must provide proof of their effectiveness through in-depth studies that can take decades — and lots of money — to complete.

“It’s been a struggle for tribal programming, for historically African American programming,” Hughes said, noting that it’s difficult for these programs to raise money to conduct proper evaluations.

Kelly Morehouse-Smith is a director who oversees programs like Effective Black Parenting at the Child Care Resource Center, a community hub that offers family services across Los Angeles. She said historically, people of color haven’t been treated fairly by the system.

“They tend to be overrepresented in child welfare, and with that comes a level of distrust of formalized services,” she said. “It’s really important to be able to have either people with lived experience who understand the community, or somebody who is ethnically or culturally similar to the population that they’re working with.”

Thomas has been teaching her class to Black parents and other parents of color for almost a year. The parents who sign up do so voluntarily, Thomas said, because they want to be around “like-minded people.”

The course, she added, is a powerful tool that can prevent families from becoming involved with the child welfare system.

“We need products and services specific to us,” she said.

The connection between poverty and neglect

There are roughly 43,000 foster kids in California, making up 12% of the nation’s foster population, according to the U.S. Administration for Children and Families. Black and Indigenous children enter foster care at rates more than quadruple their white counterparts, according to the California Child Welfare Indicators Project.

County Child Protective Services agencies usually remove children from their families and place them in foster care when they suspect a child is being abused or, more frequently, neglected at home.

In 2023, 82% of children entering foster care in California were removed for “neglect,” a broad term that can mean a range of things, from not wearing clean clothes to going to school unbathed. But the term is often linked to poverty, not true neglect, said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection, a progressive advocacy group.

“These horror stories almost always happen because overloaded caseworkers are deluged with false allegations, trivial cases and cases in which family poverty is confused with neglect,” Wexler said.

We’ve reached a point in this country where more than one-third of all children, and more than half of Black children, will at some point be subjected to a child abuse investigation.

Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection

While the raw number of Black children entering foster care in California is smaller than children of most other races, they are overrepresented. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Black kids made up 16% of children entering foster care in the state in 2023, yet Black residents comprise 6% of the state’s population.

The trend is national. Across the country, Black children made up 22% of the kids entering foster care in 2023, despite making up 14% of the population.

“We’ve reached a point in this country where more than one-third of all children, and more than half of Black children, will at some point be subjected to a child abuse investigation,” Wexler said. “They’re not all going to be placed in foster care, but they’re all going to be subjected to that, and that is one hell of a traumatic experience.”

A ‘potentially amazing resource’ without support

The federal Family First Prevention Services Act puts forward critical dollars for states like California to help curb this racial disproportionality in the child welfare system.

Under the law, programs seeking funding must undergo a thorough evaluation by a clearinghouse run by the federal government’s Administration of Children and Families.

The rating bestowed by the Title IV-E Prevention Services Clearinghouse determines whether the program qualifies for federal money. Three ratings make a program eligible: “promising,” “supported” and “well-supported.”

Many agree that the law has the potential to turn disproportionality in the child welfare system on its head. But some think the high barrier to entry – for example, the clearinghouse requirements – hinder rather than help the cause.

“It’s an underutilized, potentially amazing resource,” said Angelique Day, a professor of social work at the University of Washington. “One of the consequences we’re seeing is that there’s a tiny list of programs … because of the evidentiary requirements.”

Day has studied the clearinghouse requirements closely. She worked as a fellow on the congressional committee that developed the Family First law. She currently works with states to help implement and make sense of the clearinghouse guidelines.

But even she has misinterpreted what seemed like straightforward rules. Day developed a model in Washington state that made it into the clearinghouse as a “supported” practice. Given the work that went into it – seven years and around $700,000 – Day and her team were hoping to achieve the top “well-supported” rating, but lost out on a technicality.

“We assumed that children and caregivers were two independent populations that don’t cross over,” but the clearinghouse said the family counts as one unit. Clearinghouse officials admitted that the stipulation is not in the handbook, she said.

The bumpy road to federal approval

For programs designed to support families of color, such as Effective Black Parenting, the process to get a “well-supported” rating in the federal clearinghouse has been confusing and unclear.

Kinaya Sokoya is executive director of the DC Children’s Trust Fund for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect, which administers the Effective Black Parenting curriculum. She said the clearinghouse didn’t explain why it gave Effective Black Parenting the lowest rating, “promising,” in 2022. In a letter sent to the clearinghouse the following year, Sokoya explained that the clearinghouse conducted its review during a period of transition for the organization and requested a re-evaluation.

“I asked them to go back and review their methodology and their criteria,” she said. “They said they weren’t going to do it. That’s just not fair”

Victoria Casey, a clinical psychologist on the group’s board, told Sokoya it may be because there was no study comparing Effective Black Parenting to a similar parenting class.

Sokoya said a comparison study is unrealistic because there isn’t a similar program to compare it to.

The Administration for Children and Families did not respond to multiple requests for comment from AfroLA for more than a month.

To get the highest rating of “well-supported,” Sokoya said the Trust Fund would need to spend about $100,000 for a researcher to travel across the country to conduct evaluations for about a year, Sokoya said.

Acquiring funding to test programs tailored for families of color is one of the biggest challenges to getting a program off the ground, said Emilie P. Smith, a professor of human development and family studies at Michigan State University.

Smith, who has implemented parenting programs across multiple states, said programs that address the cultural needs of Black families are few and far between.

“We know that scholars of color already, even before this time, were less likely to get funded with these kinds of ideas. And now they’re literally prohibited,” Smith said, referring to mandates from the Trump Administration that prohibit funding for Diversity, Equity and Inclusion initiatives.

For example, the federal government this year removed a program designed for LGBTQ+ youth from being considered by the clearinghouse due to Trump’s executive order to terminate all DEI projects.

After reviewing research submitted to the clearinghouse for Effective Black Parenting, Smith noted a few drawbacks over email. First, the model was based on “coercive” parenting, which is characterized by controlling tendencies that are linked to negative development outcomes for children. Culture is “bigger than just this,” she wrote.

And the study was a “quasi” experiment, meaning that pre-existing differences in the families could be driving the parenting changes noted in the study.

Where Effective Black Parenting comes from

Effective Black Parenting was developed in the late 1970s when its founder, Los Angeles-based psychologist Kerby Alvy, saw Black children removed from their families at higher rates than other races. He began interviewing families in L.A. to develop a framework that would address parenting problems stemming from slavery and systemic disadvantages.

The program has grown since then and was lauded by former President Bill Clinton when he signed a proclamation establishing National Parents’ Day.

We don’t have white effective parenting. This is strange to me.

LaWanda Wesley, director of government relations at Child Care Resource Center in Los Angeles

Over the years, there has been criticism that the program highlights the most negative aspects of Black culture.

“There’s a lot of onus being put on Black families that our parenting isn’t effective without there being ownership” of the harm chattel slavery inflicted on Black families, said LaWanda Wesley, director of government relations at Child Care Resource Center in Los Angeles.

“We don’t have white effective parenting. This is strange to me,” she said.

At MarSell Consulting in San Bernardino County, which provides counseling and foster care services to unaccompanied minors who have crossed the U.S. border, staff recently began offering Effective Black Parenting classes. Owner Marty Sellers hired an outside consultant to revise the original curriculum and remove culturally insensitive sections.

“I think the content in there needs to be modified,” said Quintin Barfield, a former behavioral specialist who worked with youth on probation and in foster care. However, as a class facilitator and counselor at MarSell, Barfield believes the curriculum is helpful. After all, he said, it’s taught him a lot about being a parent.

Dearth of culturally-specific programs

One goal of the Family First law was to create a log of the best models across the country for states to choose from, Hughes said.

In order to qualify for the federal money, states must choose from this list of programs. At least half of the programs selected by states must be “well-supported,” the most rigorous standard.

The reason the requirements are so strict is because Republicans wanted to ensure that federal dollars were going to vetted programs, according to Hughes and Day.

To ensure programs can be applicable to families of color, the clearinghouse allows programs to be adapted in small ways to meet the needs of specific cultures. These changes include delivering the program in a different language without changing its content, or altering examples to match the culture of the families in the program.

But Casey Family Programs, an organization that provides research and guidance on foster care policy, warned that making too many changes could render a program “new,” and require it to be re-evaluated in the clearinghouse.

Basically, we have a clearinghouse deciding whether or not children and families in America are allowed to have a service.

Angelique Day, a professor of social work at the University of Washington

It’s preferable to create a program with a culture in mind from the beginning because it takes more effort to reconfigure it to fit the needs of a specific culture, said David Simmons, government affairs director at the National Indian Child Welfare Association.

“‘Culturally-adapted’ means you’ve got to take something that wasn’t really developed for your community,” he said.

In addition, Day said many of the programs in the clearinghouse were not tested on child welfare involved populations.

“I don’t think we have enough evidence as of yet to understand whether or not that is going to turn out to be a positive or negative thing,” she said.

In seven years, the clearinghouse has reviewed 210 programs and approved 95 of them. There are more than 800 waiting to be rated. So far, only 20 programs have been designated “well-supported.” Only one of those, Strong African American Families, is tailored to Black families.

So far, 25 states and the District of Columbia have received money for programs. In 2023, those states billed the federal government more than $340 million for programs, about half of which the federal government reimbursed.

California’s state-plan was approved in 2023. In it, state officials decided to include 10 programs that meet the “well-supported” designation. Despite California’s goals to address racial disparities in foster care, the chosen programs do not include culturally-relevant services.

Hughes said the federal law was “extremely restrictive and prescriptive” about program standards, resulting in a clearinghouse made of “traditional Western models” that benefited from having more money to achieve the “well-supported” rating. These westernized programs are typically well-funded and have been around long enough to have already conducted the research needed to obtain a high clearinghouse rating. He said the federal government could have done more to make dollars available for the kinds of studies needed to meet clearinghouse approval.

Had the federal government not created such strict stipulations, California would have added more culturally relevant programs, said Kathryn Icenhower, co-chair of the state’s Prevention and Early Intervention committee, which provides guidance on the state’s foster care prevention efforts.

A number of counties in California have asked the state to consider including Effective Black Parenting on its list, including Los Angeles and San Bernardino counties.

Jason Montiel, a spokesperson for the California Department of Social Services, said in an emailed statement that the state will eventually expand its list of 10 programs, but that doing so would require additional funding. If the state includes programs rated “promising” or “supported,” such as Effective Black Parenting, it must pay to evaluate the programs itself, per federal requirements.

“For that to occur, funding will need to be identified,” he said. However, adding more programs is “likely a few years away.”

“Prioritization will include those services that are culturally responsive to Black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) youth and their families,” Montiel said.

“Basically,” Day said, “we have a clearinghouse deciding whether or not children and families in America are allowed to have a service.”

‘Nobody to call’

California is also part of the problem.

Persistent delays in the implementation of a critical statewide data collection system mean the state can’t receive funding, said Diana Boyer, president of the County Welfare Directors Association of California, which represents the state’s child welfare department leaders.

The cost of the project has jumped by $1.3 billion since it was approved by state officials in 2013, according to a report from the Legislative Analyst’s Office, taking longer and costing more than any other project in its current portfolio.

The earliest California is estimated to be able to access the federal money is October 2026, after this data system is implemented, according to Boyer and Icenhower.

If we did not have these programs, Black kids would be getting overlooked all day.

Edwina Thomas, program manager for Young Visionaries

The only money the state has received so far from the law is the one-time grant to pilot programs, including culturally relevant ones, which was dispersed in 2023.

In addition, turbulence at the federal level makes it hard to know what will happen next.

Earlier this year, the Trump administration shuttered regional offices of the Administration for Children and Families across the state, and it cut the national workforce by 40%. “There’s such chaos with ACF. There’s nobody to call,” Icenhower said.

For Thomas, who works at a juvenile detention center as a counselor every Friday, any additional funding for her weekly class would be a blessing.

She said that she sees firsthand the children affected by corporal punishment. Almost all of the children she works with are Black, and many of them say they got into trouble because of how they were disciplined by their parents.

In her view, programs that allow Black parents to connect with one another are vital to children’s success.

“If we did not have these programs,” Thomas said, “Black kids would be getting overlooked all day.”