Racial Disparities in Toxic Cleanup Times Especially Pronounced in SF, Data Shows

The story was originally published by San Francisco Public Press with support from our 2024 Data Fellowship.

A toxic site in the Mission District, polluted with gasoline that leaked from storage tanks, is undergoing cleanup. Such remediations take longer in communities of color than majority-white communities.

Laura Wenus/San Francisco Public Press

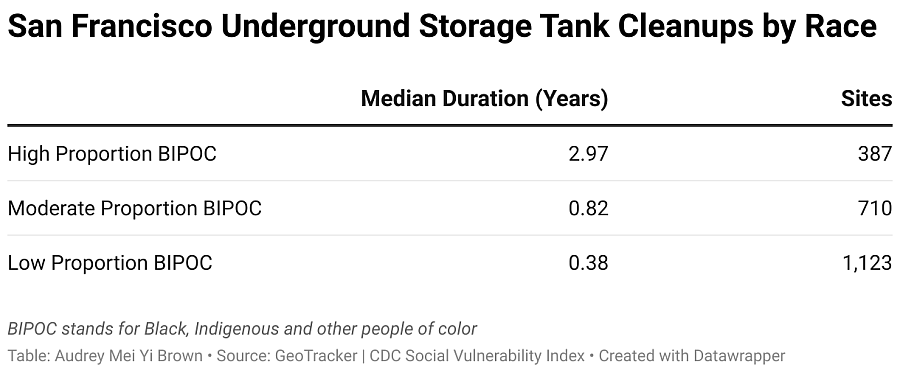

Toxic site cleanups take longer in parts of San Francisco where fewer residents are white, a new data analysis from the San Francisco Public Press shows. The analysis also shows that a higher proportion of residents who are Black, Indigenous and other people of color in an area correlates directly with longer cleanup durations.

Across all sites in San Francisco, cleanups took more than four years longer in areas with high proportions of BIPOC residents than in majority white areas. The size, complexity and nature of toxic sites varies and could account for some differences but further analysis shows that these disparities hold when comparing sites of similar complexity and size.

Strictly among comparable sites, the median cleanups in areas where two-thirds or more of residents were BIPOC took more than two and a half years longer than cleanup times in areas with a low proportion of BIPOC residents. Cleanup times across all sites showed deeper disparities based on race than on social vulnerability, a measurement that includes factors such as poverty level and household crowding. However, low-social-vulnerability areas still saw swifter median cleanups than areas of moderate and high vulnerability, by 617 days and 128 days respectively.

Cleanups happened faster overall in San Francisco than in other major Bay Area cities but the racial disparities within San Francisco were starker than those in cities such as San Jose and Oakland.

“There are many reasons why these disparities could be, but the fact that they exist means regulatory agencies should take social vulnerability and race into account when prioritizing which sites to clean up first,” said Lindsey Dillon, associate professor of sociology at UC Santa Cruz, who is part of a research group that advises the agencies.

In a written statement, a state Water Board spokesperson said the agency considers environmental justice when it prioritizes sites for cleanup, as well as other factors such as the exposure risk and a community’s history of experiencing historical racism.

The state Department of Toxic Substances Control, another agency that oversees cleanups in San Francisco, not did not provide a comment or an interview in time for publication.

Slow cleanups concern scientists, who worry about the health impacts of extended toxic exposure for nearby residents.

Local advocates and researchers found the disparities alarming in light of the Trump administration’s recent elimination of federal Environmental Protection Agency environmental justice offices and funding. Experts worry the cuts will severely curtail the agency’s ability to enforce environmental protections. That could leave marginalized communities in San Francisco even more vulnerable.

Pushed to polluted areas

Many of those communities are clustered in the city’s southeast region, which has a high concentration of industrial and former military uses that have polluted the area. Because of redlining, the region was until 1968 one of just a few places where Black and brown San Franciscans were legally permitted to live until 1968.

“Black folks weren’t able to rent anywhere else other than Bayview-Hunters Point and the Fillmore,” said Shirletha Holmes-Boxx, a community organizer and policy advocate at the watchdog organization Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice. That constraint led her family to settle in Bayview-Hunters Point, she said.

The racial disparities in cleanup times are a predictable outcome of that history to Holmes-Boxx.

“For anyone who looks like me, none of this surprises us,” said Holmes-Boxx, who is Black and a lifelong San Francisco resident. “It’s just racism, period.”

A variety of factors exacerbated that segregation, said Dillon, who has studied the Bay Area’s history of environmental contamination. Openly racist housing associations barred people of color from white areas on the north side of the city, which has borne relatively little of the city’s industry. Economic status limited where people could settle and pushed them toward the city’s southeast. Newcomers also sought community and tended to join existing enclaves.

All of these factors concentrated people of color in the city’s industrial zones. Industrial operators continue to locate facilities in those neighborhoods, where land is often relatively cheap and residents might lack clout to refuse them.

Though most San Franciscans are people of color, comparison of disparities specific to each racial group within the city was hampered by the low number of Black residents. African Americans compose 5% of the city’s population, according to census data. Too few census tracts contained moderate (one to two-thirds) or high (two-thirds or more) proportions of African American or Hispanic residents to allow for analysis.

Pollution saturation worsens disparities

Neighborhoods in San Francisco’s southeast like Hunters Point bear an overwhelming share of the city’s industry. It’s a common burden for marginalized communities across the country. As early as 1987, the report “Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States” showed communities of color bore an outsized burden of hazardous sites. In San Francisco, this pollution saturation has likely exacerbated racial disparities both in overall cleanup durations and in durations for less complex, comparable cleanups.

When a community contains many sites including a highly toxic one, advocacy organizations have to deprioritize relatively minor sites, said Bradley Angel, executive director of the environmental justice group Greenaction. One such type of site houses underground gasoline and diesel storage tanks, which can leak the fuels into soil and groundwater. The toxins can then penetrate pipes leading into buildings and rise as gases, exposing people in their homes, schools and workplaces.

The leaking underground tanks have proliferated throughout the Bay Area and were used as the comparable site dataset in our analysis because the hazards they present tend to be similar and cleanup protocols tend not to vary much in complexity.

Remediations of these sites are less complex than those for large former industrial or radioactive sites. But because of the prioritization of advocacy that marginalized communities must do, those smaller cleanups can languish.

“If you’re in Bayview-Hunters Point, are you going to focus on a leaking underground storage tank or the shipyard?” Angel said, referring to the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, which has more than 100 contaminants, some radioactive.

Richard Drury, an environmental attorney and partner at the firm Lozeau Drury LLP, agreed. Drury, who served as the legal director for the environmental justice organization Communities for a Better Environment, said that during that time he focused on major pollution sources like oil refineries.

“We wouldn’t have prioritized a little underground storage tank cleanup,” Drury said.

As a result, even in communities that have mobilized around toxic cleanups, minor sites can fall through the cracks, which means overburdened neighborhoods stay that way.

Loudest advocates get fastest cleanups

Regulatory agencies have limited staff and resources — the Department of Toxic Substances Control’s budget is less than $400 million — but advocacy can push them to prioritize a given cleanup, said Ian Wren, the lead scientist at San Francisco Baykeeper, an environmental protection nonprofit. Baykeeper’s main strategies include filing lawsuits and calling agency officials directly, he said.

“The loudest advocates typically get the fastest cleanups,” Wren said. “If people don’t comment, they largely fly under the radar.”

But hiring a private lawyer or seeking out regulatory officials requires money and time — scarce resources in San Francisco’s working class communities of color. That could contribute to cleanups happening more slowly in the city’s southeast than in its wealthier, whiter neighborhoods, Wren said.

Since moving to private practice, Drury has witnessed firsthand how affluent and privileged San Franciscans can more easily effect swift and full cleanups. Such residents have hired him. In many cases, his clients learned about planned redevelopment on polluted sites near them from posted notices. They then had the time and bandwidth to detect through further investigation that the proposed redevelopment’s cleanup plan might be insufficient to completely address the pollution on the site. These residents also have resources to pay his legal fees, which regularly exceed $50,000.

Once he’s on a case, Drury checks for contamination unaddressed by cleanup plans. If he finds it, he alerts regulators and city or county officials. He said that in more than a dozen cases, his firm spurred further cleanup and enforcement from officials at agencies like the regional Water Board and the Department of Toxic Substances Control.

But people in working-class communities of color are often too busy making ends meet to take on advocacy work, said Julio Garcia, the executive director of the South San Francisco community organization Rise South City.

“People don’t have time to go to meetings. They have work schedules where they can’t attend,” he said. And that’s if they were even aware of the contamination in the first place — which is not a given, he said. Many toxic sites are visually unremarkable and pollute their surroundings quietly.

“If nobody in the community knows about it, nobody in the community will take action,” Garcia said.

Arieann Harrison, founder and CEO of the Bayview-Hunters Point-based Marie Harrison Community Foundation, echoed Garcia.

“People are just trying to survive,” said Harrison, whose organization carries her late mother’s name because of her tireless environmental activism. That advocacy is vital for communities like hers, the younger Harrison said.

“If the community is not in uproar about it, it’ll never get resolved,” she said.

Correcting disparities may require funding

Agencies should try to correct the cleanup time disparities, UC Santa Cruz’s Dillon emphasized. Some regulators agree but advocates acknowledge that agencies’ power to do so is limited by tight budgets.

Annalisa Kihara, the state Water Resources Control Board’s assistant deputy director in the Division of Water Quality, said the agency considers equity and referred to the agency’s racial equity action plan.

Eddie Ahn, the executive director of the environmental justice organization Brightline Defense, said agencies will need money to make plans like that a reality. The Department of Toxic Substances Control’s budget of less than $400 million can be rivaled by the cost of a single cleanup, though the agency typically does not cover the full price. Remediation of severely polluted sites can cost far more.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency typically contributes relatively modest seed grants to support cleanup for toxic brownfields with planned redevelopment.

“Our funding might get you a quarter of the way,” said Michael Olokode, assistant director of the EPA’s Land Chemical and Redevelopment Division. If the landowner can’t cover the rest of the cost, a cleanup can stall, he said.

“We need to leverage new sources of funding to pay for cleanups,” Ahn said.

In the wake of the Trump administration slashing federal EPA environmental justice offices and funding, state and municipal agencies are critical to protecting the welfare of marginalized communities, say local advocates and researchers. But President Trump has taken aim at state environmental protections, too. On April 8, he signed an executive order, which legal scholars describe as unconstitutional, restricting state laws that address pollution from the oil and gas industry.

Story editing by Laura Wenus. Data editing by John Harden, a USC senior fellow and metro data reporter for The Washington Post.