The Radioactive Killer

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Sara Israelsen-Hartley, a participant in the 2019 National Fellowship.

Other stories in this series include:

How looking at an invisible gas could bring change into your home

Inside the newsroom: Ignore radon testing at your own peril

Dustin Wallis, a 39-year-old nonsmoker, receives an infusion to treat stage 4 lung cancer at Utah Cancer Specialists in South Salt Lake on Monday, Dec. 2, 2019.

Kristin Murphy, Deseret News

Editor’s note: This investigative report was produced with support from the University of Southern California Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship.

SALT LAKE CITY — It’s a warm November afternoon in Cottonwood Heights, a suburb of Salt Lake City, and the leaves are piling up in Dustin and Emily Wallis’ backyard, but Dustin isn’t raking.

There’s no time for that, or energy.

Dustin is in his living room, thinking about the tumors in his brain.

Just a little over a month ago, Dustin went to the neurologist for an MRI and hopefully some answers as to why he’d been experiencing debilitating migraines and shoulder pain for months.

He didn’t come home that night.

Instead, the 39-year-old father of two was sent to the hospital and prepped for brain surgery.

There were two tumors in his brain, a large one and a smaller one, a tumor in his shoulder and a tumor on his lung.

Doctors were cautious to not use the word “cancer” until they had more information, but Dustin and Emily knew it was coming before they actually heard the diagnosis: Stage 4 non-small cell squamous cell carcinoma — terminal lung cancer.

The horribleness of cancer is that while so many people get it, doctors don’t always know why.

Factors include everything from genetics to obesity.

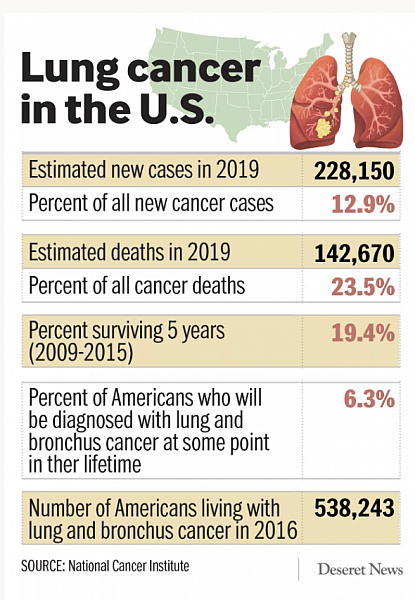

Yet lung cancer isn’t so mysterious.

Most of the time — between 80% and 90% — it’s caused by smoking.

For the remaining 10% to 20% of cases, the culprit is more complicated.

Secondhand smoke, air pollution, asbestos and exposure to chemicals are all factors.

But the second-leading cause of lung cancer, according to the EPA, is something called radon — an odorless, invisible gas. It’s the largest single exposure to natural radiation any of us will face.

In Utah alone, 1 in 3 homes, or nearly 320,000 households, have dangerous levels of radon.

Dustin never smoked, or lived in a home with smokers.

He will probably never know exactly what caused his cancer, but today he wonders if his diagnosis is somehow related to radon.

He grew up in Vernal, Utah, in one of the state’s seven high-risk counties for potentially elevated indoor radon levels.

Radon may be one of the deadliest killers in Utah, and one of the most ignored.

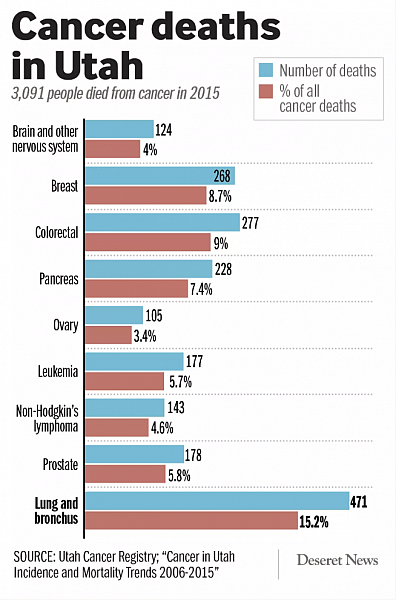

It might also be the answer to a question that has long puzzled doctors and patients: why is lung cancer the leading cause of cancer deaths in a state where 90% of people don’t smoke?

Understanding the enemy

Radon is a quiet hazard.

Unlike asbestos or diesel, it’s natural, produced as uranium decays in the soil, meaning there’s no company to blame.

There’s no smell to drive quick action, like what accompanies a natural gas leak.

And unlike carbon monoxide, it will take 20 years to kill you.

It’s “a classic case of a hazard where there’s very, very little outrage factor,” says Daniel Tranter, supervisor of the indoor air unit at the Minnesota Department of Health. “It has all the hallmarks of a risk that’s going to be perceived as low, compared to other things.”

Yet, therein lies the danger.

As radon gas bubbles up from uranium in the soil, it dissipates to near harmless levels in the outdoor environment. But when radon finds its way through cracks in foundations and settles in basements and buildings with less air circulation, it begins to accumulate. Radon can also be found in water, most often in private wells.

Radon is measured in picocuries per liter in the US, and in 1992, the EPA set an indoor action level of 4 pCi/L, based on “technology and cost.”

However, because there is “no known safe level of exposure to radon,” the EPA recommends that families consider fixing their homes if levels are between 2 and 4.

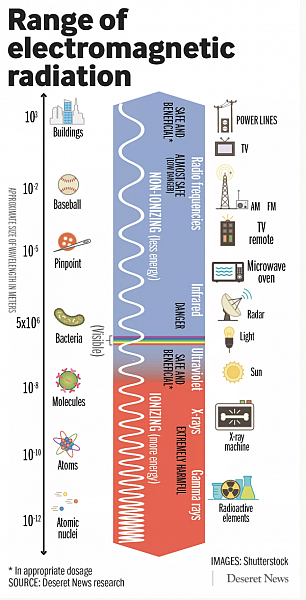

When inhaled, radon continues its own decay process in the lungs, sending off alpha particles with enough energy to damage lung cells by knocking electrons out of atoms and ionizing them.

Once ionized, some cells may die, while the body may start repairing others.

Yet if too much damage happens at once, or for an extended period of time, the cells may not be repaired correctly, leading to broken cells — the most basic definition of cancer, says Dr. Wallace Akerley, a medical oncologist at the University of Utah’s School of Medicine and director of the Lung Cancer Center at Huntsman Cancer Institute.

“It’s really important to understand that radon is really radiation,” says Akerley. “Everyone has a great fear of radiation and they’re really worried about it, but they’re missing the point about radon.”

We’re exposed to radiation every day in small amounts, through radio waves or microwaves or cellphone signals, but these sources are non-ionizing, meaning they don’t damage our cells.

Stronger forms of radiation, such as X-rays, CT scans, or radon gas, are ionizing radiation — meaning any exposure causes cell damage.

Unlike lab rats — which scientists can show get lung cancer when exposed to radon and its radioactive daughters — we don’t live in a lab, meaning it’s nearly impossible to blame radon as the sole cause of non-smoking lung cancer.

While doctors do know that small-cell lung cancer is caused by smoking, anything non-small cell is likely a mash-up of several factors that may work together to increase the risk.

That also explains why radon is so dangerous for smokers, because tobacco and radon work synergistically to dramatically increase the risk of lung cancer.

However, this damage still takes decades to manifest, making researchers especially concerned about children’s exposure to radiation.

“Kids are fundamentally sensitive to this,” and young growing cells in the lab exposed to radiation are “way worse off” than nongrowing cells, says Dr. Aaron Goodarzi, a professor and radiation biologist at the University of Calgary who studies DNA damage after radiation exposure, as well as the founder of Evict Radon, a nonprofit initiative to understand and solve Canada’s worsening radon gas problem.

Not only is the risk for DNA replication error much higher in rapidly dividing cells, but exposure at a young age could mean cancer in the prime of life, not the end.

Despite that worrisome potential, few, if any, middle-age Utahns will get checked for lung cancer, as there are no screenings for nonsmokers.

That means if a cancer does develop, someone may not discover it until stage 4, when it has metastasized to other parts of their body and by then, the odds of survival plummet.

More than half of people with lung cancer will die within one year of their diagnosis, and the five-year survival rate for lung cancer is 18.6% — far lower than the nearly 90% survival rate for breast cancer, according to the American Lung Association.

“Radon is the most important naturally occurring, preventable cause of cancer,” says Akerley, who works at the Lung Cancer Center at Huntsman Cancer Institute, where one-third of lung cancer patients are nonsmokers.

He says many of his patients not only feel shame and embarrassment with a nonsmoking lung cancer diagnosis, but also a sense of betrayal.

“I’ve had people horrified, saying ‘what kind of a government do we have here if they’re not letting us know?’” Akerley says. “They assume these houses are protected and if there was radiation in the house that the government would have protected them, and it just doesn’t.”

Lack of action

Utah has no laws or regulations for radon testing.

Instead, the state has passed one watered-down resolution that established January as radon awareness month, yet asked landlords, builders, bankers, community groups, colleges, doctors and media outlets to educate the public, while urging Utahns to take steps to protect themselves.

There’s one line about radon in the building code, and legislators have approved a few bills that funded radon awareness campaigns but generally maintain a hands-off approach in favor of personal responsibility — despite overwhelming public ignorance about the topic.

Nearly half the state doesn’t know that lung cancer is a consequence of radon exposure, and 80% of Utahns haven’t tested their home for radon, according to a 2013 Health Department survey. When asked why not, 35% of people said they’d never thought about it.

“The balance in Utah is challenging,” said Aaron Osmond, a former Utah state senator who sponsored a 2014 bill that got $25,000 for radon education and awareness. (He asked for $100,000.) “We are very conservative ... but there are times when government does need to step in and provide clear protections. That is the purpose and role of government — to protect the citizens.”

Though radon is listed in our state’s cancer plan, aside from the work of the state radon project coordinator, Eleanor Divver, (whose radon position is part-time) and a handful of citizen advocates, cancer experts and county health departments, little is being done.

“We’ve tried to take steps that we feel have been helpful,” said Rep. Keven Stratton, who has been a co-sponsor on the few radon-related bills. “Now having said that, if you take the first step and that doesn’t get it done, then you try to take another step.”

In the meantime, Utah remains virtually lawless as it relates to a known carcinogen.

That means radon tests aren’t required when buying or selling a home here.

It means no one is checking your child’s day care or school classroom for the cancerous gas.

And while thousands of new homes springing up along the Wasatch Front could be built in ways to reduce the exposure risk, it’s optional and unchecked.

Why all this matters

The days following Dustin’s diagnosis are a blur.

Before October, Dustin and Emily had devoted all their time and emotional energy into managing changes at Dustin’s work and planning to grow their family.

Today, everything is cancer.

There will be no more babies.

Whether the family of four gets two more years together or 20, it will “never be enough,” says Emily.

The Wallises will likely never know exactly what caused Dustin’s cancer, but they wish they had known about radon before now. Before cancer.

When they bought their home 10 years ago, the realtor mentioned they probably didn’t need to test for radon since their home didn’t have a basement.

They wish they had.

After testing recently, their levels came back at 2.9.

But there’s no time for wishing.

Their schedule is full of immunotherapy and radiation treatments for Dustin, fitting a radon mitigation system into their budget and keeping everyday life as normal as possible for their young children.

During my visit, we talk in the living room over the chirps of 2-year-old Annabelle and 5-year-old James who are reading books on their mom’s lap and at her feet.

Both Emily and Dustin are calm, but their smiles are heavy with worry.

At one point in the conversation, James pipes up, “Is Dad going to die?”

“Everybody dies,” Emily responds gently.

“But is Daddy going to die?” James insists with the curiosity of a preschooler who has been forced to confront the idea of death too early.

Emily pauses only slightly, “We don’t think so,” she says simply.