A Refugee Story: Trauma haunted a woman who saw too much

Claudine Mukankindi never recovered from the multiple traumas she endured.

On a Sunday morning in December, nearly a hundred people gathered in a West End church to dedicate their prayers to Claudine Mukankindi, a 36-year-old woman who came to the United States as a Congolese refugee.

Last year, she died of a heart attack.

In a pew near the front was Adeline Kihonia. Dancing and chanting in worship, she had tears in her eyes as she spoke of her deceased friend.

"She was like a part of my family," Kihonia said. "When she passed away, it was like I lost a sister, a good sister."

When Mukankindi arrived in Pittsburgh in 2001, it was after surviving the Rwandan genocide, enduring countless acts of violence and loss of family. She had fled to the Congo and then to Kenya, then Cameroon before being resettled in Pittsburgh by Catholic Charities.

With the exception of the young daughter she brought with her, she didn’t have family, but she quickly became close to Adeline Kihonia. With Kihonia, with whom she shared Congolese roots, she also shared much of what she experienced before arriving in the U.S.

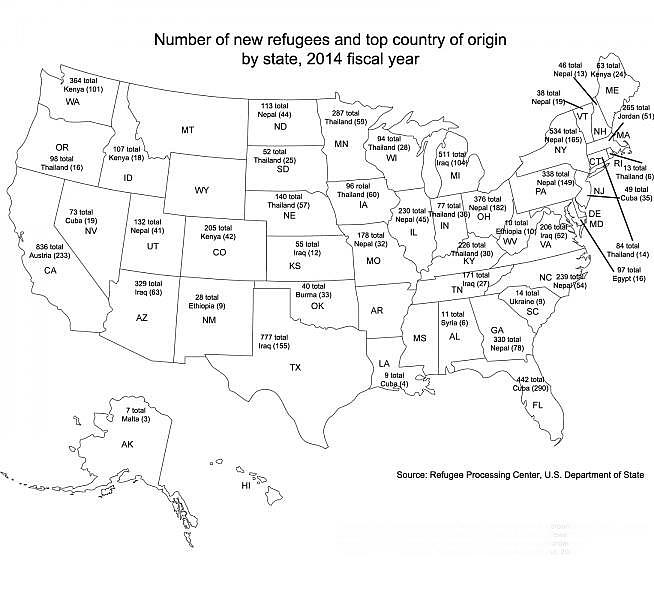

Over the next five years, 50,000 Congolese will be resettled in the United States by the U.S. State Department. According to area resettlement agencies, roughly 2,000 of them will be moving to Pittsburgh.

Many of them will come without any English language skills and with trauma, depression and other scars of war. They’ll be in need of mental health services — services that many providers and the Pittsburgh Congolese community fear aren’t going to be there.

Exporting Attitudes About Mental Health

In Mukankindi's time in the U.S., she was diagnosed and treated for a slew of mental illnesses, among them post-traumatic stress disorder. Her last years were marked by hospital stays and court visits.

"Claudine saw a lot of stuff, I don’t know if I can say some of them, but they were raping women and Claudine saw all of that and they did that to her and they killed even her uncle in her eyes," Kihonia said. "She saw a lot."

"But you know, sometimes when you already have a lot of shocks in your life, it's very difficult to go back, you know, to be really, really normal. And we try. We try, we try everything. And even (Claudine Mukankindi's) daughter. The daughter tried everything … but … we lost her."

Trauma is pervasive in the Congo and other conflicted and post-conflict countries. Lynn Lawry from Harvard Medical School has studied mental health issues there. A 2010 study she conducted in the Congo found that half of all adults exhibited symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder.In contrast, that number is between 5 to 10 percent of the U.S. population.

Despite those high numbers, Lawry said there are little-to-no mental health services in the Congo.

"In most of the countries that I go to that are countries of conflict or post-conflict, there may be one psychiatrist or two psychiatrists, which was the case for Democratic Republic of Congo," she said.

Lawry said different cultural norms in the Congo may not allow people to realize that what they are experiencing is a form of mental illness. When people emigrate, those attitudes are exported.

Jean Elomba, a Congolese man who was resettled in Pittsburgh around the same time as Claudine Mukankindi, agreed.

"Back home, people don’t know all the diagnoses of mental health, other than just being crazy in general," he said.

He too had experienced traumatic events. One has left an enduring physical scar — a gunshot wound followed by days of hiding in fear without medical attention resulted in him losing his right arm.

For the first eight months refugees are in the U.S. they receive federally subsidized medical assistance that covers their medical needs. When Elomba arrived, he was fitted for a prosthetic arm. But he said he was never offered mental health care, even though in retrospect, he might have benefited from it.

"It was very difficult, because you don’t go to sleep, because you keep dreaming about all the things and you feel like someone’s going to come to get you," Elomba said. "You have all those bad dreams. You keep dreaming the same thing over and over."

Even though he struggled in the Congo and in the U.S., if mental health services had been offered to him, Elomba doesn’t know if he would have partaken.

"You don’t want to just talk about anything because what will they think about me when I say those things," he said. "So you try to withhold some information and think, well, maybe I’ll overcome this and maybe someday I’ll feel better."

Elomba said religion helped him with his struggles, but he knows that some people like Mukankindi may have greater needs.

Not everyone who experiences trauma develops post traumatic stress disorder. It's not known why some people develop PTSD and others don’t.

Elomba ended up working as a caseworker for several years with Catholic Charities, the same group that resettled him. He would often try to direct new refugees toward the proper channels, especially people that were coming from war-torn areas.

"Again, there is this stigma that is attached to mental health," he said, "because back home if you start talking of things like that, people see you like you are crazy, and you don’t want to be seen as crazy."

Because he lacked knowledge of the mental health system, and he wasn’t sure what providers were available with the necessary language skills, he would often just refer people to primary care providers. He said he often thinks about his friend Claudine Mukankindi — if her life would have been different if she had received mental health services immediately upon her arrival to the U.S.

"I think there was a big missed opportunity when she came to try to stabilize her," Elomba said. "She should have gotten mental health care and entered into a treatment program."

Trauma Upon Arrival

In Mukankindi’s first few years in the U.S., she learned English and made friends within the Congolese community. There were also hospital visits and loss of mental stability. Along the way, she lost custody of her daughter, which friends say devastated her.

In 2006, she ended up at Bethlehem Haven, a homeless shelter.

She spent the last few years of her life at Bethlehem Haven’s long-term, supported homeless shelter for women with severe mental illness.

"When we looked at the story and we think to ourselves, if I was in the middle of a civil war, if I saw people die in front of me, if I had to live in a tent, if I was taken from my family for whatever reason, and had to live in refugee camps and then applied for a lottery system that says if I am one of the people drawn from the lottery, I’ll get a ticket to America with my daughter..." said Lois Mufuka Martin, the shelter’s executive director.

She said that in some cases, supports refugees get upon arrival — housing, food and health care for the first few months — aren’t enough. She has seen other refugee women show up at the shelters.

"People fall into homelessness after initial supports have dwindled..." Martin said, "housing, a stipend, someone to talk with all the time. After the supports have dwindled, we find them at our doorstep."

Of course, for others, it is enough.

"I think the gap is not understanding for different people, the transition can take longer without those continuous supports. And those supports are outside of the mental health supports," Martin said. "When she came, she (Mukankindi) had the regular refugee supports. Perhaps had the refugee supports been included, she could figure out her level of trauma coming from a war-torn country, maybe her initial stay here would have been different."

In the years Claudine Mukankindi was at Bethlehem Haven, her daughter was adopted by her friend Adeline Kihonia. Mukankindi's mental health was stabilized. She got a job, and in 2010, she became a U.S. citizen. But last December she died unexpectedly.

Martin said trauma doesn’t just affect the mind, it affects the body.

"In our world of homelessness, we’ve been known to say that for every year a person is homeless it ages them up to 10 years," she said.

Finding Grassroots Support

Although the World Health Organization and the State Department recognize that many refugees are coming with trauma upon arrival, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has guidelines for mental health screenings, those that work in the resettlement agencies and those who have gone through the screen say the screen is weak.

And the screenings done before refugees come to the U.S. are for communicable diseases like tuberculosis or AIDS.

And some, like Martin, say the act of resettling itself can be traumatizing. There may be some time between when refugees arrive and when mental health symptoms flare up.

"We’ve always wondered about the level of trauma, and if in any way being here re-traumatized her, if any of the situations in this country unintentionally re-traumatized her," Martin said. "And we’ll never know that answer."

Martin said many of the problems Mukankindi faced are pervasive within the refugee community: poor English skills, little-to-no medical literacy, not knowing how to self-advocate and a lack of a safety net. With a growing refugee population in Pittsburgh, she said there has been talk within the mental health community that while Pittsburgh may have housing and employment for them, there may not be supportive services in place.

"Mental health is grossly underfunded as it is," Martin said. "Homeless shelters, permanent supportive housing with 24-hour support is grossly underfunded, so what I am hearing in a general conversation is how do we absorb additional populations, be it indigenous or not. How do we absorb them into systems?"

One way may be grassroots.

Rebecca Cech spent her childhood in the Congo and frequently returns. She is on the Congolese resettlement committee Allegheny County has set up to address some of the issues they may face. She said many of the refugees they are expecting are single mothers, women who may have some of the same vulnerabilities as Mukankindi.

Cech said while the initial supports refugees get are invaluable, it's not necessarily enough.

"Everything they do works on the assumption that people are of sound mind and sound body to a degree," she said.

Cech is working with others in the established Congolese community to set up homegrown support systems and connect new refugees to mental health services. Similar efforts are also underway in the Bhutanese and Somalian refugee communities in Pittsburgh.

"You can help them in all kinds of ways, but unless there is a support system for them in that way, there are still really serious issues, and you're talking about people who have been victimized," Cech said, "so trust comes really slowly. And it's really difficult to talk about some of the things that have happened to them, and there is not a culture in Congo of that kind of support outside of family and friends networks."

This story was produced as a project for The National Health Journalism Fellowship, a program of USC's Annenberg School of Journalism.