RI landlords are required to ensure their units are safe from lead paint. But who checks?

The story was originally published in The Public's Radio with support from our 2023 National Fellowship.

Edson Pereira and Suany Ortiz walk into their new home. While living in a previous apartment, a test showed their daughter had been lead poisoned.

Jodi Hilton for The Public's Radio

Shortly before their daughter’s first birthday, Edson Pereira and his fiancée Suany Ortiz moved into the third floor of a triple-decker in downtown Newport. It was the first apartment the family had to themselves. At the time, Pereira said he worked down the street, and their in-laws lived nearby.

When their daughter Harper was 19 months old, in May 2021, the couple took her in for a routine procedure in Rhode Island: a lead screening test. To Pereira and Ortiz’ surprise, the results showed she had lead in her blood.

Six months later, another test showed the level had increased.

And a year after the first test, Harper’s lead level had more than doubled.

“It shouldn’t be in her system,” Pereira said. “There’s nothing that says you should not worry about it.”

Harper is one of the roughly 500 children a year who are lead poisoned in Rhode Island. Most cases result from exposure to toxic lead paint, according to the state health department.

“There’s a lot of children going through that right now,” Pereira said. “And, I feel like there’s nothing being done about it.”

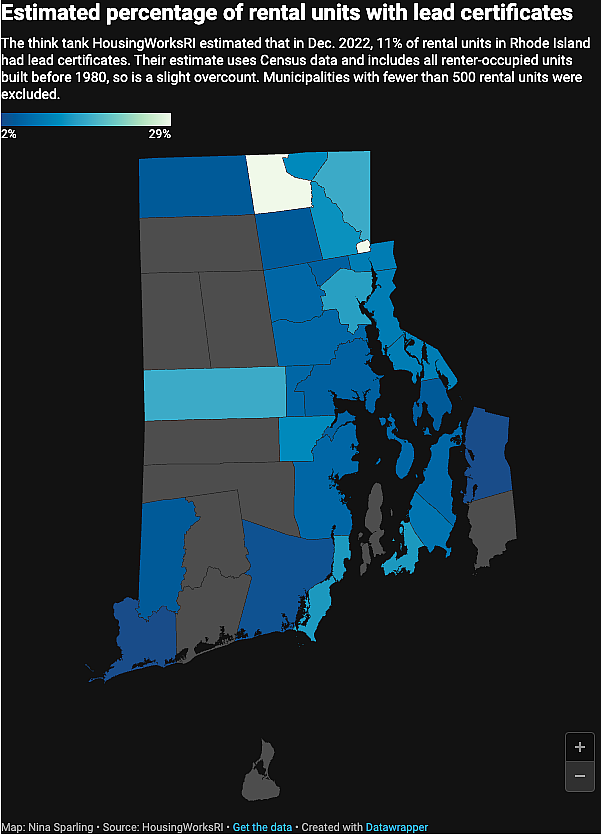

For most rental housing, Rhode Island law requires landlords to regularly inspect units and obtain “lead certificates” showing they’re safe from immediate lead hazards, like peeling or pulverized paint. But according to records obtained by The Public’s Radio and interviews with dozens of experts, landlords rarely face consequences for failing to obtain the certificates, leaving tenants in the dark about the potential hazards in their homes.

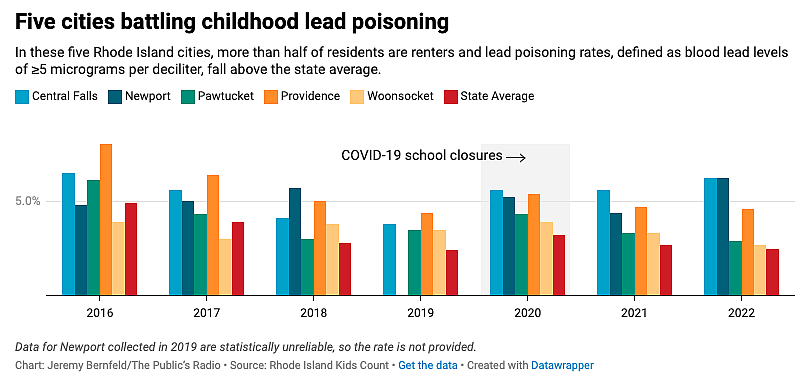

Estimates from the think tank HousingWorksRI show the vast majority of rental housing units lack the legally required lead certificates. The Public’s Radio focused reporting on Central Falls, Newport, Pawtucket, Providence, and Woonsocket, the five Rhode Island cities where more than half of residents are renters and where the lead poisoning rates fall above the state average.

“There is kind of a lack of understanding and cohesion throughout the state that it is the city’s responsibility to enforce the requirement to have a lead certificate,” said DeeAnn Guo, a community organizer with the Childhood Lead Action Project, an advocacy group focused on eliminating lead poisoning in Rhode Island. “That’s something that is failing tenants.”

The Childhood Lead Action Project canvasses neighborhoods to alert tenants and homeowners about their rights and responsibilities.

Jodi Hilton for The Public's Radio

A known toxin

The house Pereira and Ortiz moved into was built in 1890, when industry still added lead to paint to help it dry faster, last longer, and resist moisture more easily. The federal government banned lead paint in 1978, but that did little to rectify the gallons and gallons already coating the walls of people’s homes across the country.

Most of Rhode Island’s rental housing stock was built before 1978, an indication it likely contains some amount of lead-based paint. That poses the most acute risk to children under six. The paint can fall off window sills into chips that children might eat, attracted to the pigment’s tell-tale sweetness. It turns to dust against the friction of doors and windows coated in lead paint. The dust clings to the sticky fingers of toddlers who use their mouths as much as their hands to explore their surroundings.

Ingested in high quantities, lead can cause seizures, thrust children into comas, even death. At the lower levels more common today, research shows the toxic heavy metal can lead to lower IQ scores, reduced academic performance, and behavioral conditions like ADHD. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there is no safe level of lead in the body.

“We’re talking about irreversible damage,” said Dr. Chandan Lakhiani, who runs the lead clinic at Hasbro Children’s Hospital. “We’re talking about neurologic and neurocognitive and behavioral issues that can persist for a lifetime.”

Exposure to lead has dramatically fallen since the 1970s as federal and state regulators have taken steps to protect children — widely considered a great public health success. But nationwide, half a million kids still experience lead poisoning every year, and disparities persist. Children in families with low-incomes experience lead poisoning at disproportionate rates. Black and Hispanic children are more likely than white children to experience lead poisoning, too.

Getting rid of lead paint altogether is expensive. Instead, Rhode Island has focused on reducing exposure by requiring property owners to obtain so-called “lead certificates.” The Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH) issues these when landlords can show a unit passed an in-person evaluation by a certified lead inspector. But the certificates are temporary, often issued for two years, and show only that a given home at the time of inspection doesn’t present immediate hazards like peeling or chipping paint — not that a unit is lead-free.

“It's really a way to prevent childhood lead poisoning,” said Cindy Singleton, an administrator with the health department team that works to prevent childhood lead poisoning. “Certificates are a way to act as an enforcement for landlords to have their house inspected.”

Cities and towns are in charge of enforcing property maintenance codes, which include the requirement that landlords obtain lead certificates. But instead of working proactively to identify problems and ensure tenants are safe from lead poisoning, municipal code enforcement offices often rely on complaints to identify violations. For years, many of the cities from which The Public’s Radio reviewed records enforced the lead certificate laws sparingly — despite evidence that increased enforcement can help reduce lead poisonings.

“It’s such a preventable disease,” Dr. Lakhiani said. “It’s something we can deal with if we’re proactive about it.”

Suany Ortiz helps her daughter Harper find a snack. While they were living in a previous apartment, a test showed Harper had elevated levels of lead in her blood.

‘Do you want children to be lead poisoned?’

Once Pereira and Ortiz learned about Harper’s elevated blood lead levels, the family said they started hearing from other Latino families in Newport that their children had been lead poisoned, too.

“A lot of the kids that we know are suffering from the same thing,” he said.

At four years old, Harper still doesn’t speak, and Pereira said doctors suspect she has autism. Studies show children with autism may be at higher risk of lead exposure, but research does not show that lead exposure causes autism.

Even so, knowing their daughter ingested a toxic substance as a toddler troubles Pereira and Ortiz as they watch her grow up. The effects of lead poisoning can take years to manifest.

“It's like being in the dark sometimes,” Pereira said, “not knowing what the future's going to be like.”

Pereira is not the only parent in Newport concerned with lead poisoning. Twenty children in Newport were lead poisoned in 2022, equivalent to 6.2% of children tested, more than double the state average.

That year, the Newport city council passed a resolution stating that, in an effort to better protect children, the city would “bring all non-exempt units into compliance” with the lead certificate laws. As far back as 2017, organizers from the Childhood Lead Action Project scheduled meetings with the building department in Newport about city-level enforcement of the lead certificate laws, according to emails reviewed by The Public’s Radio.

Yet the city has no record of ever issuing a citation to a landlord for a missing lead certificate.

“It's unconscionable,” said Beth Nitkin, who runs the Women, Infants, and Children program at the East Bay Community Action Partnership, a social service organization with offices in Newport. Nitkin said she is currently working with nine children in the city with elevated levels of lead in their blood.

“They're not addressing a real issue,” she said, referring to Newport city officials. “I mean, do you want children to be poisoned?”

Newport City Hall on January 12, 2024.

Jodi Hilton for The Public's Radio

City Councilor Lynn Ceglie introduced the resolution. The city, she said, has made progress through campaigns educating landlords about their responsibilities, but increasing enforcement should play a critical role in preventing lead exposure, too.

“It's like getting a speeding ticket,” she said. “People start talking about it and then they realize ‘Oh, there’s police out there.’”

Ceglie is working with William Moore, the city’s building official, on ramping up enforcement of the certificate laws in the coming months. Still, Moore said tackling the issue will be challenging for the department to take on. Newport has just one housing inspector covering the whole city.

“We'd love to do it and we're going to try and do it,” Moore said. “But I wouldn't want to put a schedule on that until I see how the beginning of 2024 goes.”

Absent additional resources, Moore said that until a family has experienced a problem with lead paint, the other demands on his time, like managing building permits and ensuring construction sites are safe, have taken priority.

“Until we know there's a problem, it's not as important as where the problems are,” Moore said.

The city does make sure contractors applying for permits to work on buildings built before 1978 have the proper training to work with lead hazards, Moore said. And if his office learned of a lead poisoning case where the landlord wasn’t fixing hazardous conditions, Moore said he would address it immediately and work to bring the property owner into compliance with the lead laws.

But he said in the year and a half he’s worked for the city, he hasn’t been notified about children getting sick.

“I'm not aware that the city of Newport has a problem with kids testing high levels of lead,” he said. “I would like to know.”

Of the five cities from which The Public’s Radio reviewed records related to enforcement of the lead certificate laws, Newport stands alone in its lack of enforcement. Housing inspectors in Providence, Pawtucket, and Woonsocket all check if a property has a lead certificate in a public database when a complaint comes in about any building standards issue, like a lack of heat or faulty electricity. Building officials in those cities also cited a lack of resources as a barrier to ensuring more widespread compliance.

In Providence, this process has identified a few hundred violations of the certificate law every year for the past decade, according to city records. Data The Public’s Radio obtained from the state health department shows that in December 2021 there were at least 6,700 uncertified units in the city. The data does not account for certain types of multi-unit buildings, so the actual count is likely many thousands more.

Last year, the complaint-driven process turned up 23 properties without certificates in Pawtucket, according to the city. In 2022, 51 children, or 2.9% of children tested, were lead poisoned in the city.

“It's frustrating, it absolutely is,” said Carl Johnson, who oversees code enforcement in Pawtucket. “Just knowing that children are living in some of these conditions.”

Central Falls is unique in that the city proactively searches for properties without lead certificates independent of a complaint or a lead poisoning, work it funds through a grant from Rhode Island Housing.

Attorney General Peter Neronha speaks to students in Central Falls about the risks of lead paint on October 24, 2023.

Jodi Hilton for The Public's Radio

‘There’s absolutely no time to do that’

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha decided his office needed to deepen its focus on the hazard lead paint poses to children in the state a few years ago.

The attorney general’s office has long played a role in enforcing the lead laws in the state — though usually only after a child has been poisoned at high levels. If property owners don’t comply with orders from the state health department to make repairs to their units and obtain lead certificates, the agency notifies the attorney general’s office, which can then take them to court. But for years, Neronha said, landlords got away with not coming into compliance.

“Orders are useless if there's no ability or will to use an enforcement tool,” Neronha said. “You have to do it.”

When Assistant Attorney General Keith Hoffman proposed the office reinvigorate its focus on lead poisonings, his team found landlords who had been issued notices of violation by the health department a decade ago yet never faced repercussions, according to Neronha.

“That's unacceptable,” Neronha said. “That's a decade of children rotating through those apartments that are getting lead poisoned or potentially lead poisoned.”

Since 2021, Hoffman and his team have sued 22 landlords for violations of the lead poisoning prevention laws in Rhode Island. But Hoffman noticed another layer: the law gives municipalities the authority to penalize landlords for failing to obtain the required lead certificates, whether or not a child was lead poisoned. Few cities or towns, he learned and The Public’s Radio investigation confirmed, were using this proactive authority.

In 2022, the attorney general and the health department issued a memo to Rhode Island’s cities and towns clarifying their power, and responsibility, to enforce the lead certificate laws. They issued further clarification last year, and again, earlier this year.

“Cities and towns, alongside the Rhode Island Attorney General’s Office and the Rhode Island Department of Health (‘RIDOH’), have a key role to play and the tools necessary to protect children from the devastating and permanent injuries that can be caused by lead,” Neronha’s office wrote.

Local code enforcement offices have been adjusting. J. Aaron Broccoli, who leads the code enforcement division in Woonsocket, and his team started regularly citing property owners for not having lead certificates in 2020, after the city received a grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development that offers homeowners forgivable loans to cover the costs of lead abatement.

“There hasn't been strict enforcement,” Broccoli said. “You're required to do this, but there was no penalty for not doing it really, unless there was a [lead] poisoning.”

Like Providence, Woonsocket largely relies on complaints about other issues to identify properties. In the past four years, the city has issued about 500 citations for uncertificated units. According to records obtained by The Public’s Radio, as of June 2022, nearly 6,400 units in Woonsocket were out of compliance with the lead certificate law. The city says attempting to bring those units into compliance proactively is beyond the scope of the code enforcement division.

“ We're not just going to properties and looking if they have a lead certificate violation,” said Michael Debroisse, the city planning director, who oversees code enforcement. “There's absolutely no time to do that.”

‘We don’t know who these people are’

Part of the problem cities and towns face in proactive enforcement of the lead certificate laws is figuring out which rental homes should have lead certificates in the first place. Currently, the state lacks a comprehensive list of rental properties, and cities often don’t keep these lists either.

“I have scratched my head ever since I found out we didn't know who the landlords were,” said Cindy Singleton, of the state health department. “I wanted to contact them, and that's when it hit me: we don't know who these people are.”

The health department has received funding from the CDC to start rectifying that problem. The department hired a data analytics firm to create lists of the rental units in cities with high rates of lead poisoning that should have certificates but don’t. So far, such lists exist for Central Falls, Providence, and Woonsocket, and the health department says the contractor is in the process of creating lists for Pawtucket and Newport.

Using those lists, in April 2022, the department sent postcards to the owners of those properties, alerting them they needed to obtain lead certificates, but didn’t track the impact of that action. This spring, Singleton and her team plan to mail out another round of postcards to landlords without lead certificates to notify them of their obligations, and of available funding to help cover the costs of repairs.

Last year, the attorney general’s office pushed for legislation to further ease the burden on cities to enforce the lead certificate law. The General Assembly passed a law that would create a registry of all rental properties in Rhode Island, contingent on available funding. To register, landlords have to submit a valid lead certificate.

The registry bill also prohibits landlords from evicting tenants for nonpayment of rent if the unit lacks a lead certificate, and allows tenants to pay rent into an escrow account if their unit has not been certified.

In Gov. Dan McKee’s proposed 2025 budget legislation, he proposed allocating $1.3 million to create the registry, but the proposal would significantly narrow its scope and delay its launch for a year — a move some landlord groups support.

“What's another year when this has been going on for, I don't know, 50 years?” said Keith Fernandes, president emeritus of the Providence Apartment Association. Fernandes said he has some apartments where he needs to renew the lead certificates, but is finding many lead inspectors are booked up as more and more landlords are rushing to get units certified.

The Providence City Council is also considering legislation to build a local rental registry, and create a proactive home inspections program in the city.

Last year also brought the end to a long-standing exemption from the lead certificate requirement for owner-occupied multi-family properties, meaning thousands more units will now have to get lead certificates.

Edson Pereira and Suany Ortiz play with their daughters on a Friday afternoon. Their eldest was lead poisoned while they were living in a previous apartment.

Jodi Hilton for The Public's Radio

‘I didn’t want another child to be born in that kind of environment’

The apartment Edson Pereira and Suany Ortiz moved into didn’t have a current lead-safe certificate when they moved in, according to the health department. At the time, the couple didn’t know to ask about lead certificates or lead paint hazards.

“I didn't think in this day and age we would still see that kind of stuff affecting kids,” Pereira said.

He said the WIC office in Newport, which provides benefits and nutrition guidance to low-income families, educated the family about ways to reduce Harper’s lead levels through dietary interventions, like eating more leafy greens and taking multivitamins. And Pereira said the WIC office also explained he could request the state health department send a lead inspector out to the apartment. Ortiz was pregnant at the time.

In July 2022, an inspector visited the property, according to documents obtained by The Public’s Radio. The apartment failed the inspection. The results show the inspector identified lead paint hazards in a bedroom, the bathroom, and the stairway the family walked up when they came home.

Pereira said a conflict with the landlord pushed the family to move out a few months later. Plus, they no longer felt safe raising a family there.

“I didn't want another child to be born in that kind of environment,” Pereira said.

Ortiz asked The Public’s Radio not to name the landlord or the property because it could impact her business, an independent house cleaning company in Newport. According to the state health department, the landlord addressed the lead hazards soon after receiving the inspection results.

“A lot of families go through this,” Ortiz said in Spanish. “And that’s why they don’t speak up.”

The Public’s Radio reviewed the Pereira-Ortiz family timeline and lead test results with three experts, who said their daughter’s elevated lead level was likely linked to the hazards in the apartment, though could not definitively rule out other potential sources of exposure. And after the family moved, their daughter’s lead level dropped.

Today, Pereira and Ortiz live in a small rental house in Middletown. Harper attends a preschool for children with special needs a five-minute drive away, and their in-laws live in a house down the street. Their new home received a lead certificate on January 2.

And their one-year-old is due for her first lead test soon.