The Sixth and Mission death corridor: assaults, brain trauma and homicide

This is part eight of a series of articles examining the relationship between housing loss and death in San Francisco.

Part One: Looking for death on the streets. And finding it.

Part Two: Gunpowder on the street

Part Three: Will losing your home kill you?

Part Four: Hidden in plain sight: dying and homelessness

Part Five: Be selfish, give a gift to a homeless person

Part Six: Living and dying in the Tenderloin: substance abuse and Nate

Part Seven: Starving in the Financial District: Ken and food insecurity

Part Nine: Steve, Tori and the Western Addition: Raising children without a stable bed

Part Ten: Mary, Melodie and the Mission district: Women brutalized on our sidewalks

If you are sent to live on the streets, it is for most people the same as being sent, without a mouth guard or helmet, into a boxing ring. A ring where the gong never sounds and there's no rope to mark the place where someone could take a swing and blow out your eye socket.

Doesn't matter if you're 75, or 14, girlishly femme or profoundly disabled. In fact, studies show, those traits will make you even more of a target. And being mentally ill will also make you more of a target - for both physical AND sexual assault.

Just think about that for a moment. Night is falling. You have one bag of stuff that you're hoping doesn't look too appealing, or someone will rob and/or beat you up for it. If your coat is really warm, or your sleeping bag too nice, someone may beat you up for those, since, unlike a bag, they're harder to take without a confrontation. A puffy new coat that seemed like a blessing only hours ago is suddenly making you very nervous. As the night picks up steam, fights are breaking out around you, people shouting and shoving as cars roll past. You see a head slammed against a bin, a fist connect with a jaw, blood dripping over a split lip. Will you stay under a bush, or wedge yourself behind a dumpster? How dark will you want your clothes to be? How carefully will you keep your eyes averted? How well will you sleep - tonight or any other night?

Rampant, frequent assault, and the constant, unremitting fear of it, comes with a health cost - and one that may not be apparent immediately. Besides the obvious high-cost injuries that require emergency care with lingering disfigurement, disability, and years of chronic pain, research has shown there are also less visible effects that can profoundly affect functioning and mortality decades later. No one knows yet the exact toll of chronic, unremitting stress on the immune system, but never-ending lack of sleep and adrenal excess has been shown, even among those warmly housed and healthily fed, to be associated with higher rates of diabetes, high blood pressure, depression, and depressed immune function. Add to those the devastating health hits of intermittent starvation, chronic substance abuse, and poor/no access to timely health care, much less preventative care and markedly higher mortality rates among the homeless for treatable medical conditions start to make sense.

And, among the types of assaults, repeated head trauma is shockingly common, and often severe, among those without a home. Brain injury can be severe enough to impair obvious function - but that often still does not change the fact that you're going back onto the street. Even when less severe, and with no obvious, crude effects, brain injury can have insidious effects, as we're discovering with football players. Brain injury is documented to cause both short- and long-term loss of impulse control, problems with rage, clinical depression, and loss of executive functioning, like the ability to stick with a goal, or defer rewards. It has even been associated with both higher rates of substance abuse and decreases in social connections - even decades later.

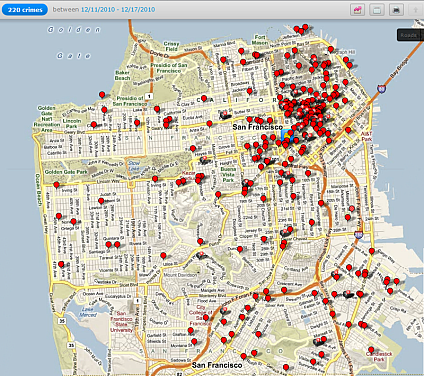

If you want an eye full of just how concentrated assaults are in our high-density homeless areas, check out the SFPD crime mapping site. Keep in mind when you look at that blood red cross positioned exactly over 6th and Market, that these numbers are only the very tiniest tip of the iceberg of what happened in that one week. The vast majority of assaults among those without a home go unreported. The taboo among the homeless against calling police is deeply ingrained, and for very good reasons.

If you're homeless, probably the most important reason to not call for help (assuming you've got the luxury of a cell phone) is that, when you're homeless, you can never get away from your assailant. He might go to jail, or he might just disappear into the metalwork. After a call - whether arrested or not - even if you are able, and lucky enough, to move to another area, you're likely to find him standing in line behind you at one of the two major warm food sites, or in the same shelter, or going to the same clinic. Or, even if he is jailed, his friends are all still in your area. You have no door you can lock. Even if you can move into a single room hotel (the temporary digs of many struggling in and out of homelessness), the culture and the violence and the same people are often still there.

The second major reason people on the street may not call for police help may be related to police attitudes, which can vary widely. Which is not to imply that policing among the homeless is ever easy. Done well, it takes a phenomenal amount of judgment, skill and insight, under extraordinary high-stakes situations, with people whose culture and norms may be dramatically different.

Check out this video, below, for a wonderful story from Melody, who suffers from OCD, ADHD, and has a history of significant brain trauma that has affected her short-term memory (among other functions). Melody was sleeping under a bush in 2008 when another homeless man offered to let her sleep in his car while he slept in a van. A car in the Bayview is where she is living now. Her story is about when she was arrested. It's a great example of how complicated and difficult things can get when homelessness and policing collide (even when everyone's trying to do the right thing). It's hard to tell who, in the end, was more traumatized by the experience - her or the officer:

If you are sent to live on the streets, it is for most people the same as being sent, without a mouth guard or helmet, into a boxing ring. A ring where the gong never sounds and there's no rope to mark the place where someone could take a swing and blow out your eye socket.

Doesn't matter if you're 75, or 14, girlishly femme or profoundly disabled. In fact, studies show, those traits will make you even more of a target. And being mentally ill will also make you more of a target - for both physical AND sexual assault.

Just think about that for a moment. Night is falling. You have one bag of stuff that you're hoping doesn't look too appealing, or someone will rob and/or beat you up for it. If your coat is really warm, or your sleeping bag too nice, someone may beat you up for those, since, unlike a bag, they're harder to take without a confrontation. A puffy new coat that seemed like a blessing only hours ago is suddenly making you very nervous. As the night picks up steam, fights are breaking out around you, people shouting and shoving as cars roll past. You see a head slammed against a bin, a fist connect with a jaw, blood dripping over a split lip. Will you stay under a bush, or wedge yourself behind a dumpster? How dark will you want your clothes to be? How carefully will you keep your eyes averted? How well will you sleep - tonight or any other night?

Rampant, frequent assault, and the constant, unremitting fear of it, comes with a health cost - and one that may not be apparent immediately. Besides the obvious high-cost injuries that require emergency care with lingering disfigurement, disability, and years of chronic pain, research has shown there are also less visible effects that can profoundly affect functioning and mortality decades later. No one knows yet the exact toll of chronic, unremitting stress on the immune system, but never-ending lack of sleep and adrenal excess has been shown, even among those warmly housed and healthily fed, to be associated with higher rates of diabetes, high blood pressure, depression, and depressed immune function. Add to those the devastating health hits of intermittent starvation, chronic substance abuse, and poor/no access to timely health care, much less preventative care and markedly higher mortality rates among the homeless for treatable medical conditions start to make sense.

And, among the types of assaults, repeated head trauma is shockingly common, and often severe, among those without a home. Brain injury can be severe enough to impair obvious function - but that often still does not change the fact that you're going back onto the street. Even when less severe, and with no obvious, crude effects, brain injury can have insidious effects, as we're discovering with football players. Brain injury is documented to cause both short- and long-term loss of impulse control, problems with rage, clinical depression, and loss of executive functioning, like the ability to stick with a goal, or defer rewards. It has even been associated with both higher rates of substance abuse and decreases in social connections - even decades later.

If you want an eye full of just how concentrated assaults are in our high-density homeless areas, check out the SFPD crime mapping site. Keep in mind when you look at that blood red cross positioned exactly over 6th and Market, that these numbers are only the very tiniest tip of the iceberg of what happened in that one week. The vast majority of assaults among those without a home go unreported. The taboo among the homeless against calling police is deeply ingrained, and for very good reasons.

If you're homeless, probably the most important reason to not call for help (assuming you've got the luxury of a cell phone) is that, when you're homeless, you can never get away from your assailant. He might go to jail, or he might just disappear into the metalwork. After a call - whether arrested or not - even if you are able, and lucky enough, to move to another area, you're likely to find him standing in line behind you at one of the two major warm food sites, or in the same shelter, or going to the same clinic. Or, even if he is jailed, his friends are all still in your area. You have no door you can lock. Even if you can move into a single room hotel (the temporary digs of many struggling in and out of homelessness), the culture and the violence and the same people are often still there.

The second major reason people on the street may not call for police help may be related to police attitudes, which can vary widely. Which is not to imply that policing among the homeless is ever easy. Done well, it takes a phenomenal amount of judgment, skill and insight, under extraordinary high-stakes situations, with people whose culture and norms may be dramatically different.

Check out this video, below, for a wonderful story from Melody, who suffers from OCD, ADHD, and has a history of significant brain trauma that has affected her short-term memory (among other functions). Melody was sleeping under a bush in 2008 when another homeless man offered to let her sleep in his car while he slept in a van. A car in the Bayview is where she is living now. Her story is about when she was arrested. It's a great example of how complicated and difficult things can get when homelessness and policing collide (even when everyone's trying to do the right thing). It's hard to tell who, in the end, was more traumatized by the experience - her or the officer:

But here are two recent, particularly egregious examples in the news: here and here. Officially, when contacted for this story, SFPD stated that, despite the unique vulnerability of homeless victims, SFPD does not keep statistics on assault victims who are homeless.

In fact, when asked for the numbers of homicides, their tally didn't even include the horrifying 5/18/2010 homicide of Pearla Ann Louis. Here's exactly what was reported by SFPD - "Year-to-date 2010 data through Dec. 9 was reviewed. Of the total of 47 homicides, one, possibly two victims were homeless: 1) On 7/27/2010, a homeless victim was killed by a homeless suspect. 2) On 8/28/2010, a victim was found near an unattended shopping cart; narrative does not specifically say victim was homeless. Percentage: If one victim of the total of 47 homicides was homeless, this gives a Citywide percentage of 2.1%; if two victims were homeless, this would be 4.3% of the total." Adding the obvious homicide death of Pearla Louis, the most likely percentage of homicide deaths among the homeless here is 6.4%. Given that San Franciscans without a home make up, at most, an even 1% of the population, that puts the homicide death at 6 times the proportion of the resident population, and an eye-popping 7 times the homicide rate for the housed. While these numbers are small, they are remarkably consistent with what has been found in studies in numerous cities across the globe. When it comes to being painfully vulnerable on the streets, a victim actually is not just like any other victim.