Starving in the Financial District: Ken and food insecurity

This is part seven of a series of articles examining the relationship between housing loss and death in San Francisco.

Part One: Looking for death on the streets. And finding it.

Part Two: Gunpowder on the street

Part Three: Will losing your home kill you?

Part Four: Hidden in plain sight: dying and homelessness

Part Five: Be selfish, give a gift to a homeless person

Part Six: Living and dying in the Tenderloin: substance abuse and Nate

Part Eight: The Sixth and Mission death corridor: assaults, brain trauma and homicide

Part Nine: Steve, Tori and the Western Addition: Raising children without a stable bed

Part Ten: Mary, Melodie and the Mission district: Women brutalized on our sidewalks

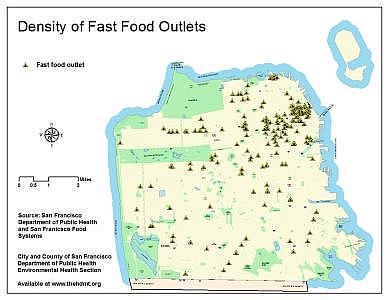

Ken sleeps under a sheltered overhang in the Financial District, an area full of sun-glinting towers and chic lunchtime hot-spots. Our own map of the Top 100 restaurants shows a hefty number clustered there, including such luminaries as Yank Sing, Aqua, and Boulevard.

I personally know these restaurants are fabulous, because I’ve been in a lot of them. But for Ken, this entire area is a complete food desert. In fact, with no money, a right leg amputated at the knee (due to an infection), no prosthesis, and living completely dependent on a wheelchair that has, at times, been stolen, and a brother to push him over our city’s hills and curbs, it’s quite a trek for Ken to make it to a location where’s there’s a food possibility at all. Especially considering the fact that many establishments, even of the more affordable sort, might not let him in the door. Corner markets and drug stores – the homes of potato chips, processed meats and, often, cheap alcohol – are many times the most welcoming.

And Ken has no option, ever, of preparing his own meals. Random fresh fruits and vegetables may be a possibility for others, but like most people who’ve been homeless for a prolonged period of time, Ken has no teeth, and no hope of dentures, which severely limits those choices. Without a home or a sink, he has, in fact, no option of merely washing anything (hands or food) before he eats. Like street-living people across America, he is utterly dependent on the cheapest of prepared food options.

Even if he can find a cheap prepared-food option in the Financial District, those options are all likely to be of the most unhealthy variety. In a best case scenario, Ken’s life might be seen as a real-life re-creation of the movie, SuperSize Me. Only this time, with bouts of starvation scattered between the liver-affecting faster-food meal choices.

But choosing based on health may not be the mindset of someone who has, repeatedly, starved. Studies have documented, over and over, the influence of food insecurity. Among the housed, food insecurity can drive people to make poor-quality food choices. Faced with an uncertain supply of food, people tend to choose the larger-quantity, lower-quality food option, even when aware of the health risks. That is how deeply ingrained into our make-up is the fear of doing without.

On the street, when it comes to food, like all other areas of health, the pressures are even more extreme. People do, in fact, experience frank starvation, with no access to food of any kind for one to several days. If you are faced with not just food insecurity, but, instead, calorie insecurity, people tend to pick the highest-calorie option available. Over and over. As Nate, hollow-chestedly thin, said in the previous article of this series, “I try to eat some ice cream every day.”

The problem is not just food, either. Without a sink, drinks must be bought, so the ones chosen are typically never plain water, but are, instead, shakes, chocolate milks, slushy coffee drinks, and other calorie-dense options such as hot chocolate. And mingled in between calorie-dense drinks are often alcoholic drinks, which are known to impair immunity and raise blood pressure. No one homeless, absolutely no one, seems to drink water. Ever. Even soda drinks do not often make the cut – being too thin and relatively calorie-poor.

And the total volume of liquid drunk (except among severe alcoholics) is shockingly small. No matter what your stand on homeless people’s access to toilets, no homeless person wants to have to pee more than a couple times a day if he or she can help it, if for no other reason than that you are incredibly vulnerable while either actually peeing, or desperately searching for a place to pee. And God help you if/when you ever wet yourself. Even for people who have become severely impaired, wetting yourself is a crushing loss of basic human dignity, besides the fact that you may, in the winter’s bone-shaking cold, have soaked your only set of clothes and/or blankets. Wetting yourself means ruining these irreplaceable items forever, since laundry facilities you can access/afford are almost non-existent. These (even distant) threats of being vulnerable while peeing, or wetting yourself on the street, is enough, at least subconsciously, to deter most people from drinking any more than they can get away with.

So in addition to low-level starvation, mingled with doses of only the worst of junk food, there is also chronic, low-level dehydration. It’s a situation that undoubtedly affects kidney function, healing, blood pressure regulation, and, as all of us recognize from our own dull headaches from not drinking enough, general well-being.

You are what you eat and drink. And you become more so as time passes. Imagine viewing this pattern day in and out over months and years as a real-time health experiment: putting a person through extended periods of 1-3 days of frank low-level starvation, overlaid with intermittent doses of only the absolute worst the American food industry has to offer.

The closest similar situation I personally have recently seen is that of Haiti, where, say, a cast for a fracture would be taken off after the indicated period of time (6-8 weeks after the earthquake), but even in a young, not-visibly-malnourished person, the bones would still not be healed. Over and over this was seen – even if the person had been well-nourished and middle-class prior to becoming a refugee of the sheet cities. That 6-8 weeks is how soon such severe stress, sleep deprivation and food/water insecurity can make a measurable impact on healing.

All of this, among the homeless here, is against a backdrop of increased metabolic demands from continual low level trauma, infections, pressure-cooker stress, and sleep deprivation. It would be hard to say what kind of health-hit such a scenario creates, but it’s no wonder homeless people tend to heal more poorly and die more quickly of almost every known health problem.

For the homeless, compared to those with more “normal” sustenance, the time frame from a first symptom, to death, may be telescoped from weeks to days, from days to hours, and from hours to minutes, all while the person is often unable to access care. And this rapid progression of disease can occur after, as Ed describes it, “the street teaches you not to feel.”

When the cumulative impact is seen all together, suddenly the shocking mortality rates among the homeless, for what are essentially treatable medical problems, begin to look more understandable – even without taking into account all the other ways homelessness brutalizes a person.

The good news

There are many groups and agencies trying to address the problem of hunger in America. But many of them are being hit hard by the economic downturn – both in terms of increased need, and decreased donations. A recent CNN report shows that hunger is at its highest level since the government starting tracking the issue 15 years ago, with one in 7 households having difficulty. We here in San Francisco are blessed not only with many people working in this area, but with twin pillar organizations that shoulder a tremendous proportion of feeding those desperately in need of a warm meal. Both Glide and St. Anthony’s EACH feed approximately 2,400 people A DAY. Let that number just sink in for a moment. It’s actually mind-boggling. Glide tends to feed around 800 at each of three meals, while St. Anthony’s feeds the entire whopping number (an average of 2,600 meals a day, nearing 3,000 on many days, or about a million meals a year) all at one mid-day meal a day. And, in areas hit hard by homelessness and the lack of fresh food options, two initiatives have made serious inroads. The Civic Center Farmers’ Market provides a breathtakingly beautiful counterpoint to the urban “food swamp” of the Tenderloin area, where fresh food options are severely limited for residents who have few choices and are often living on the edge of homelessness. And two men have made it their own private enterprise to create a gorgeous garden, complete with fruits and vegetables, out of what was a trash-strewn corner lot. All with their own money and sweat equity, while opening it up to seniors and schoolchildren in this neighborhood.