Suicide Rates Spike for Black Youth Even as Systemic Barriers Thwart Mental Health Care

The story was co-published with the Sacramento Observer as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

Students from three high schools came together for Student Voices, an event organized by Impact Sac on Feb. 12 to connect with leaders and give them an opportunity to be heard.

Roberta Alvarado, OBSERVER

Like many Black teens across the country, Duchess-Angelica Wright struggles to maintain her mental health. As a young Black woman, a member of the LGBTQ community, and a former foster youth, she faces multiple layers of challenges.

She says academic pressure and financial difficulties create constant stress. But the real turning point came in 2022 when she came out to her foster mother, triggering suicidal thoughts and self-harm.

“I’ve thought to kill myself time and time again,” Wright, 17, tells The OBSERVER. “I’ve been fighting a never-ending battle ever since I came into the system.”

After coming out, Wright was hospitalized three times between October and December 2022 for attempted suicide. Each time, she was held for 72 hours and then released. Instead of receiving support from her foster mother, Wright was kicked out of the house in April 2023, just before the end of her sophomore year of high school.

Feeling unloved and unwanted, she frequently contemplated suicide. She says the intersectionality of being Black, LGBTQ, and in the child welfare system has been a constant burden.

“As minority teens, we always have to fit society’s needs, act a certain way, speak a certain way, or code-switch, and that in itself is a big stressor,” Wright says.

Duchess-Angelica Wright, 17, attempted suicide in 2022. Though now in a much better head space, she still struggles with her mental health.

Roberta Alvarado, OBSERVER

Fortunately, Wright was able to reconnect with her older brother, who took her in nearly two years ago. However, Wright is under the impression that she cannot access mental health care because of a legal conflict with her adoptive mother, who remains her legal guardian. However, in California, students 12 years of age or older can consent to outpatient mental health treatment or counseling without parental consent, if the mental health professional deems them mature enough to participate, according to the California School-Based Health Alliance.

Wright says she doesn’t want to become another statistic in a larger crisis, one reflected by her struggles.

Suicide among Black youth is rising at an alarming rate. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, youth ages 10-24 account for 15% of all suicides. Between 2018 and 2021, suicide rates among Black youth increased by 19%.

In 2022, suicide was the second leading cause of death for U.S. youth ages 10-14 and the third leading cause of death for youth and young adults aged 15-19. Black youth ages 10-24 have experienced a nearly 37% increase in suicide from 2018 through 2021, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

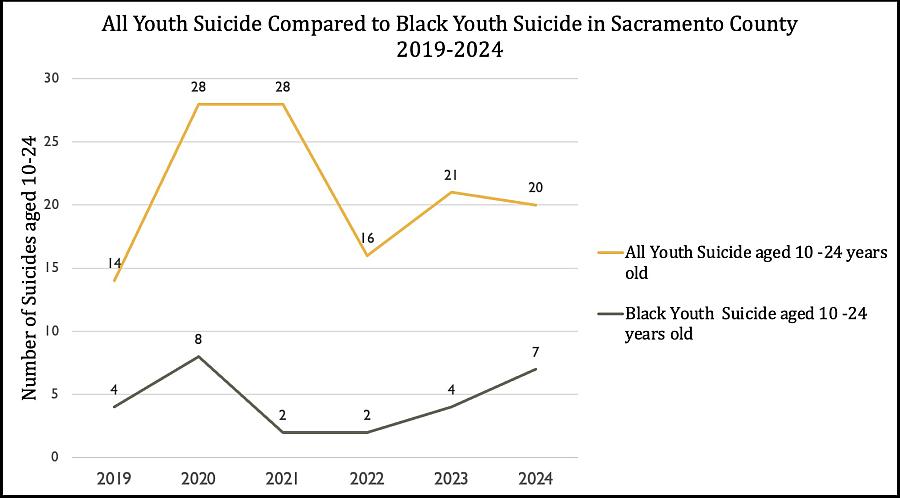

In Sacramento County, suicide was the third leading cause of death among youth ages 10-24 from 2010 to 2022. The OBSERVER analyzed county data and found that Black youth comprised roughly 21% of all suicides in that age group from 2019 through 2024. While overall suicide rates are declining, they are increasing among Black youth, particularly among young Black men, who die by suicide at more than four times the rate of Black women.

Suicide attempts are also more frequent among youth. According to Sacramento County Public Health data for November 2024 though January, 60 youth were admitted to an emergency room for attempted suicide and more than 600 visited the emergency room because of suicidal thoughts.

Sacramento County youth suicides and Black youth suicides in from 2019 through 2024. Black youth made up 21% of suicides in that period while Black people make up roughly 11% of Sacramento’s population.

Robert J. Hansen, OBSERVER

Black youth face unique mental health stressors due to discrimination, poverty, and systemic inequities. Higher suspension rates and increased interaction with the juvenile justice system disproportionately affect Black Students.

The mental health of Black youth is also negatively affected by mass incarceration. Despite Black youth making up roughly 14% of the population, Black youth comprise 42% of the total population of incarcerated youth and are almost five times as likely as their White peers to be detained in juvenile facilities at some point in their lives.

A 2024 survey on the mental health of LGBTQ+ young people showed that 41% considered suicide, and 14% attempted suicide in the past 12 months.

Youth with a history of child protective services interaction are three times as likely to die by suicide than children without such history. A study conducted by Kidsave and Gallup in 2021 showed that Black children are about 14% of the U.S. child population, yet made up 22% of the foster care system.

Community-Based Solutions

To address these challenges, local organizations are stepping into the breach to support Black youth mental health.

The Center at Sierra Health Foundation is the leading organization in Sacramento when it comes to addressing the Black youth mental health crisis and is partnered with many nonprofit organizations and throughout Northern California.

The Foundation receives funding toward its youth suicide prevention from local, state and federal agencies.

In 2021, Sacramento County Behavioral Health Services partnered with and funded The Foundation to develop the Community Responsive Wellness Program, which provides outreach, engagement and prevention services for Sacramento’s Black communities. The program has supported Black youth ages 25 and younger who need mental health support and might otherwise be victims or perpetrators of violence. The killing of Stephon Clark by local police is a consistent reminder that a community-based, trauma-informed approach is needed to ensure the safety and well-being of Black people in Sacramento.

“There was a recognition by the community regarding gaps in culturally responsive services that took into account mental health and barriers to accessing mental health services for community members who historically didn’t see therapy as something that was available to them,” says Amaya Noguera, program officer with the Community Responsive Wellness Program.

The program also addresses basic needs such as housing and food, recognizing that mental health support extends beyond traditional therapy.

“With our unique approach … we would get to know that individual to understand the holistic landscape of what that individual is dealing with,” Noguera says.

Noguera told The OBSERVER that over the past year and half, the program developed another component by providing up to 12 free therapy sessions for those who are economically disadvantaged and without insurance.

With suicide rates among young Black men rising, advocates say more safe spaces are needed.

“Young Black men have told me they don’t feel safe expressing their emotions out of fear of judgment or misunderstanding,” Noguera says. “There has to be more spaces where they can take off the mask or armor they carry throughout their day.”

Since 2014, My Brother’s Keeper Sacramento, managed by the Sierra Health Foundation, has worked to improve health, education, workforce, and juvenile justice outcomes for young men of color. Program officer Ray Green notes that many young Black men internalize negative stereotypes, which impacts their self-worth and mental well-being.

“Sacramento was one of the first sites to respond to the call for My Brother’s Keeper to be launched,” Green says.

Young Black men in Sacramento have told Green that a lack of resources in impoverished communities, being exposed to violence and not seeing schools as centers of wellness for them.

Green says his team’s research found that because of pervasive hypermasculinity within their social circles, young Black men struggle with discussing the challenges they face.

“What often happens is they lash out behaviorally because they don’t know any trusted adults in school spaces to speak to about their issues, so it results in negative behavior,” Green says.

He adds that Black men too often are characterized as being violent and don’t see many Black role models within the schools. The biases of some teachers may have led to higher suspension rates, which contributes to the school-to-prison pipeline, Green says.

Green’s work fights back on those narratives and brings young men together. That gives them the opportunity to discover commonality of feeling and helps them realize that they are not alone and not the problem.

“It’s poor policies, practices and systems that are in place producing these poor outcomes,” Green says.

Green says Sacramento’s data resembles the national trend of increased young Black suicide. He thinks that increased isolation during the pandemic and the racial reckoning following George Floyd’s murder have a major impact on the mental well-being of young Black men.

Building Community Support Networks

The Race and Gender Equity Project, or RAGE, which began in 2016 by working on youth research and healing projects, expanded during the pandemic because of the need to be able to support people remotely as they suffered in isolation.

The RAGE Project is a grantee of the Sierra Health Foundation’s Youth Suicide Prevention Media and Outreach campaign, Never a Bother, a statewide campaign designed to reduce suicide, suicide attempts and self-harm for disproportionately impacted youth.

Dr. Stacey Ault, founder and CEO of RAGE, says the project was born out of a collective anger at systemic inequities and injustice with a mission of advancing the well-being of Black women and youth through healing, education, advocacy and research.

“We’re interested in dismantling those systems that harm and reimagining spaces where Black youth can be free and actively working to build those spaces,” Dr. Ault tells The OBSERVER. “We see ourselves as an infrastructure of support for youth and community members that want to create change in whichever space they’re in.”

RAGE has a youth-led coworking healing space on Florin Road that gives young people space to be themselves.

“With all the community centers closing down and after-school programs becoming limited, Black youth really need spaces where they can be non-policed, where they can be supported and can build relationships with each other,” Ault says.

Dr. Ault is disheartened and enraged about the increase in youth suicide. She feels for Wright. She’s afraid there will be even fewer resources for mental wellness under the Trump administration. Dr. Ault wants Wright and others like her to know the problem is the environment that was created before they were born; she encourages those in need to use their anger to demand the help they need.

“There are people that will help. When the system doesn’t work, the community always works,” Ault says. “Find your people, they got you.”

For Wright, life has improved since moving in with her brother. She hasn’t self-harmed since December 2022 and has been free of suicidal thoughts for about a year. However, academic pressure still triggers anxiety.

Her school principal has provided unwavering support, helping her gain acceptance into three CSUs and a college in St. Louis.

“Without her, I would not be graduating this year,” Wright says.

She has found solace in weightlifting, saying it has significantly improved her mental well-being. “Lifting weights took the weight off my shoulders.”

If you would like to be connected with and possibly receive 12 free culturally competent therapy sessions, visit https://communityresponsivewellness.org to be connected to the Community Responsive Wellness Program. For any additional inquiries Program Officer Amaya Noguera at aabhp@sierrahealth.org. Those interested in learning more about or becoming involved with My Brother’s Keeper Sacramento can email mbksacramento@shfcenter.org. More information about the RAGE project can be found at https://www.rageproject.org.

This article is part of The OBSERVER’s special series, “Crisis Call: Addressing The Mental Health Challenges Of Black Teens.” The project is being reported with the support of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California, a yearlong venture with print, digital, podcast and broadcast outlets across California.