They weren’t faking: 12 young detainees who died while under Florida’s care

This article and others in this series were produced as part of a project for the University of Southern California Center for Health Journalism’s National Fellowship, in conjunction with the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

Other stories in the series include:

Powerful lawmaker calls for juvenile justice review in wake of Herald series

Juvenile justice chief defends agency, calling abuses ‘isolated events’

An officer used a broom to beat juveniles into submission. They called it ‘Broomie.’

NAACP demands reform as lawmakers plan tour of lockup where youth was fatally beaten

Criminal record? Horrible work history? Florida juvenile justice would still hire you

At this juvenile justice program, staffers set up fights — and then bet on them

Dark secrets of Florida juvenile justice: ‘honey-bun hits,’ illicit sex, cover-ups

Lightning blasted his shoes off — and illuminated a pattern of abuse by staff

How small rebellions by Florida delinquents snowball into bigger beatings by staff

FIGHTCLUB: A Miami Herald investigation into Florida’s juvenile justice system

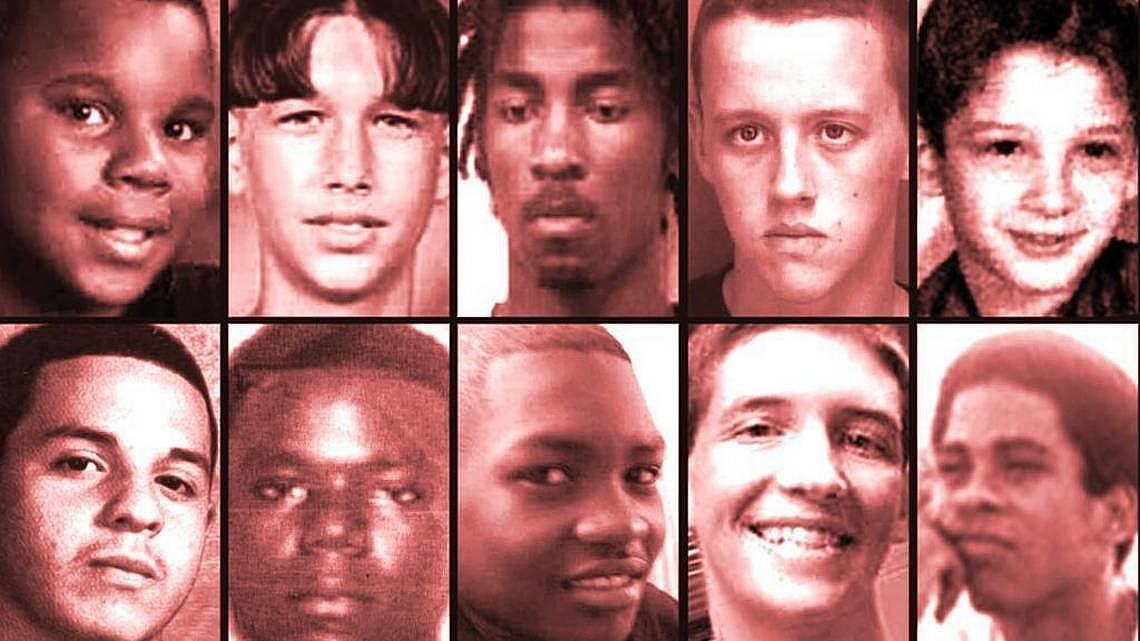

Top row, from left: Andre Sheffield, Anthony Dumas, Martin Lee Anderson, Daniel Matthews, Michael Wiltsie; bottom row: Daniel Huerta, Omar Paisley, Elord Revolte, Shawn Smith, Eric Perez. Not pictured: Willie Durden and Dillon Tyler Peak

Whether because of bad policies, bad decision-making, bad healthcare or abusive staff, Florida’s juvenile justice system has experienced sporadic deaths. Here is a timeline.

Feb. 5, 2000: Michael Wiltsie, 12

Michael Wiltsie

What Michael needed most was mental health treatment. What he got was the full weight of a 300-pound man on top of him, making it impossible to breathe.

In a lawsuit, Michael’s mother, Linda Ibarra, said that staff at Camp E-Kel-Etu in Marion County insisted Michael be removed “cold turkey” from his psychiatric medication, and that he was given no therapeutic services to cope with his bipolar disorder and behavioral problems.

Investigations concluded Michael, a willowy boy at only 66 pounds, died of asphyxia after being held in a “full-body restraint” by a counselor. Michael “kept yelling that he could not breathe,” a death review said. The counselor said he remained on top of the boy anyway, “because he believed the child was ‘playing possum.’ ”

Ibarra learned of the incident from hospital staff, as the program “did not make any attempts to notify her” that Michael had been gravely hurt, the Department of Children & Families death review said. Prosecutors said they could not find evidence that the counselor “acted with utter disregard for Michael’s safety,” and so declined to file charges. Ibarra never recovered from the boy’s death. Six years later, she took her own life — and that of her other son, 7-year-old Lorenzo.

“She was so broken. It just broke my heart. I felt horrible for Lorenzo. He needed his mom, and she wasn’t there for him. She couldn’t be.” — Linda Ibarra’s lawyer, Guy Rubin, to the Miami Herald

Oct. 14, 2000: Anthony Dumas, 15

Anthony Dumas

Anthony hanged himself with a leather belt from his bunk bed at a Broward County juvenile justice shelter. A caregiver might have saved his life by cutting him down. Instead, she snapped pictures to document events as he suffocated.

Police reports said three staff members were on duty that night at the Lippman Youth Shelter — which had operated unlicensed for four years — and all failed to cut him down.

Anthony, still alive, was not released from his noose until police arrived, and officers were shocked to see him still tethered to his belt. Anthony died after four months in a coma. Three youth counselors were ordered fired by the Department of Juvenile Justice, and the counselor with the Polaroid camera was convicted of child neglect. She was under house arrest for a year.

At the counselor’s sentencing, Anthony’s father said it would be hard for him to forgive the workers who failed to give aid to his dying son. “The only time we get to see Anthony now is at the grave site,” said Walter Dumas. A prosecutor suggested the counselor perform community service at the cemetery — an idea that a Broward judge rejected.

“He wasn’t supposed to die. He was supposed to come home.” — Shirley Finley, Anthony’s mother, to the Herald three days after her son succumbed to his coma

Oct. 30, 2001: Shawn Smith, 13

Shawn Smith

Shawn was supposed to be under “close watch” as a suicide risk, but he was able to take his life anyway. He was found in his cell at the Volusia Regional Detention Center with a sheet tied to his neck and to the door of his cell. Under DJJ protocols, lockup officers were required to observe him every five minutes.

When the agency’s inspector general’s office looked into Shawn’s death, investigators learned that the surveillance tapes were gone — making it difficult to determine whether the boy had been properly supervised. The investigation concluded that nine lockup officers failed to abide by suicide-prevention policies; three were suspended, and a fourth was fired.

May 31, 2003: Daniel ‘Danny’ Matthews, 17

Danny and another youth had traded insults all day from cells at the Pinellas County Regional Juvenile Detention Center. When a guard mistakenly opened the two detainees’ doors, the two squared off in a hallway.

Daniel Matthews

Danny struck first, according to the boy who hit him. After the two exchanged punches, Danny collapsed on the floor. He died of blunt head trauma, either from a blow to his temple or the fall that resulted. A senior detention officer was fired and an assistant superintendent was suspended.

Danny’s mother later said she had agreed to have her son arrested when he pushed her at home. He was abusing drugs and had become volatile.

“I finally had my son arrested so he could get help ... and now he’s dead. ... I don’t care what the kid did. There’s no reason for this.” — Diana Matthews, to the St. Petersburg Times, on June 2, 2003

June 9, 2003: Omar Paisley, 17

It took authorities at the Miami Regional Juvenile Detention Center three days to treat Omar’s worsening appendicitis. It was one day too many.

Omar had complained to nurses and guards that he was sick and in excruciating abdominal pain. He wept and retched and moaned, curled in a fetal position.

“Man, someone needs to get down here, because this kid is sick,” an officer implored over the telephone. But two nurses — and a platoon of officers — waited days before summoning help as their supervisors said they lacked the authority to call for an ambulance. Some of the officers and nurses thought Omar was faking.

Omar’s death came to symbolize what lawmakers at a series of hearings called “a culture of neglect” within DJJ. Twenty-five DJJ employees, including Secretary William “Bill” Bankhead and the lockup’s superintendent, either resigned or were fired, and the two nurses were charged with third-degree murder. One pleaded guilty to culpable negligence and was sentenced to a year’s probation. Prosecutors dropped charges against the second nurse.

Nearly 15 years later, grand jury forewoman Constance Portela, a Miami businesswoman, still recoils: “Animals are treated better,” she told the Herald.

“This is not something that will go away. This is a scar. The wound may heal, but the scar is there to remind you.” — Cherry Williams, Omar’s mother, to the Herald in November 2004

Oct. 13, 2005: Willie Durden, 17

Willie was described as a “model inmate” who aspired to be a youth counselor. The counselor who was supposed to be his role model instead watched him die.

Just after 4 a.m., a youth worker at Cypress Creek Juvenile Offender Correctional Center heard a “gurgling” sound coming from Willie’s room. The guard and his supervisor waited 20 minutes before summoning help or beginning CPR, all the while “yelling at the kid to wake up,” the supervisor told investigators.

The worker explained his inaction this way: “Some of these kids will play pranks.”

An autopsy concluded that Willie died of ventricular arrhythmia, due to an enlarged and diseased heart.

“How do you hire for common sense? Would you wait 20 minutes if this were your child?” Nancy Hamilton, then president of the state Juvenile Justice Association, asked the Herald on Aug. 21, 2006, when a report on the boy’s death was released.

A youth in the room next to Willie’s told DJJ that the teen had been making the best of his stay at the program, and had encouraged other boys to turn their lives around, as well.

“I think my purpose in life is dealing with children [to] let them know where I’ve been and how I turned my life around by fulfilling my purpose on Earth.” — Willie Durden, in a book report days before he died, as reported in the Herald

Jan. 6, 2006: Martin Lee Anderson, 14

Martin was sent to the Bay County Boot Camp for joyriding in his grandmother’s Jeep. He left the same day, in an ambulance.

The teen had been ordered by “drill instructors” to run laps around a track. He said he couldn’t run anymore. The officers accused him of malingering, and they punished him with a violent takedown.

Almost a half-hour after the guards began the restraint — which included punches to his arms and knee jabs — Martin stopped breathing.

An autopsy by a Tampa medical examiner — appointed by a special prosecutor — later determined that the boy was suffocated when guards held his mouth shut and repeatedly shoved ammonia tabs up his nose. Throughout the takedown, a nurse stood by and watched.

The grainy videotape of the restraint — released following a suit by the Herald — shocked the state. “This could be anybody’s son,” a Miami lawmaker said.

Seven guards and the nurse were charged with manslaughter but later acquitted. Then-Gov. Charlie Crist signed the “Martin Lee Anderson Act,” which closed all military-style boot camps that used physical violence and pain to force compliance with rules.

“[Martin] was just trying to do what he was told to do. But he passed out and they still beat him. They tortured him.” — Robert Anderson, Martin’s father, to the Herald in March 2007, when Gov. Crist offered the family $5 million in compensation

June 17, 2006: Dillon Tyler Peak, 14

Dillon was hospitalized twice in four days during his stay at the Peace River Outward Bound Wilderness Camp in DeSoto County. He developed a high fever, about 104 degrees, and was hospitalized with strep throat, then released back to the program.

His caregivers were told to treat him with over-the-counter medication. A few days later, he woke up “groggy and disoriented,” a statement said, and he was returned to the hospital having seizures. He apparently died of a severe case of encephalitis. His mother sued Outward Bound, claiming he was not given proper medical care. The suit was settled out of court.

“This is quite sad. The student was at our facility for about six months, had completed almost all of his goals. He was due for release in a couple of weeks.” — Statement from the program to a state lawmaker

July 10, 2011: Eric Perez, 18

Perez marked his 18th birthday at the Palm Beach Juvenile Detention Center. He’d been sent there after officers spotted a broken light on his bike and arrested him for a small amount of marijuana.

The night before he died, a guard dropped him on his skull during what investigators described as “horseplay.” In the hours that followed, he retched, hallucinated and complained of monstrous head pain.

Staff sought “guidance” from a nurse, but she didn’t return calls. Video footage, never released, depicted Perez’s limp body being dragged on a mat from his room to a common area of the lockup and then back again — a sign that officers thought he was ill and were worried he might infect other detainees.

Records indicate lockup supervisors and the superintendent instructed subordinates not to call 911. By the time paramedics were summoned, Perez showed only a “flat line” on a heart monitor. He died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Then-DJJ Secretary Wansley Walters fired six lockup employees, saying: “We will not tolerate employees who violate policies and procedures that are in place to protect the health and welfare of our youth.”

“They killed him in there. ... Just because he made mistakes doesn’t mean they have the right to take his life away.” — Maritza Perez, Eric’s mother, to the Herald, in the days after Eric died

Dec. 8, 2011: Daniel Huerta, 17

Daniel Huerta

Daniel was loaded into a Ford Expedition for a trip back to his wilderness camp from a sporting event. He never arrived. His driver, Johnson Atilard, swerved off a roadway while making a turn in Collier County. The SUV crashed into a traffic sign before plunging into a canal.

Daniel drowned, as did Atilard, who had been ordered away from the steering wheel of any AMIkids company vehicle. Police and troopers had ticketed him 18 times in the five years before the crash, including infractions for speeding, driving an “unsafe” car, making an improper turn and running a red light.

He’d also been charged with giving alcohol to a minor. Atilard was driving with a suspended license that night. The Florida Highway Patrol said he was speeding and talking on his cellphone.

“Big Cypress insurance will not cover you. Failure to abide by these restrictions places AMIkids Big Cypress in a position of great liability.” — Feb. 1, 2011, memo from Big Cypress’ director to Johnson Atilard, months before the crash

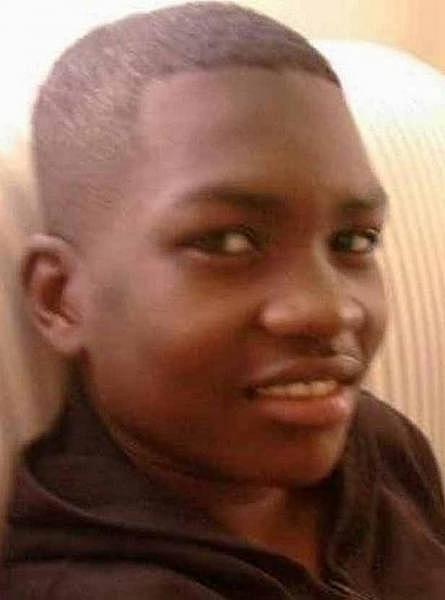

Feb. 19, 2015: Andre Sheffield, 14

Andre complained for days of a headache and stomach pain, soiled himself, limped, lost his balance and fell down. A nurse gave him Tylenol. He died of bacterial meningitis.

A DJJ report on the boy’s death said the Brevard Juvenile Detention Center violated agency rules regarding the treatment of sick detainees, though details of Andre’s final hours remain sketchy. Detainees said Andre had complained repeatedly of leg, stomach, head and neck pain. The youths said he was trembling and limping around the module. Officers insisted Andre exhibited no signs of distress until shortly before he died.

The 50-page report also faulted the lockup’s top officer for failing to ensure that officers under her command were properly trained in agency sick-call procedures. She was suspended for five days.

A nurse who was faulted for failing to follow a medical protocol for diagnosing abdominal pain was fired when she refused to cooperate with an investigation.

“Andre was a fine, loving kid. He smiled all the time. ... He was anxious to get home, and play with [the family’s new] puppies.” — Berlena Sheffield — Andre’s grandmother, who raised him — to the Herald when DJJ released its report on his death.

Aug. 31, 2015: Elord Revolte, 17

Elord Revolte

When Elord died, his possessions were being stored in a black garbage bag on the back patio of a Miami Beach foster home. His short-lived foster mom asked a caseworker to retrieve them.

In one of the bags was a notepad with penciled verses: “Son of god. I’m just a brother,” one of them ended.

In his last months, Elord caromed from the home of a cousin to an aunt to a lockup to foster care and into the streets of South Beach. Back at the Miami detention center on armed robbery charges, Elord was beaten to death by at least a dozen teens.

Cause of death: blunt force injury of head, neck and chest.

Video of the assault shows a huddle of teens in khaki pants punching and kicking Elord. One officer pulled the initial aggressor off him while another called for help on a radio. But more than a minute elapsed before officers were able to rescue Elord, and by then the damage was done. A vein beneath his left collarbone slowly seeped blood until he collapsed.

Two youths told prosecutors the attack was a setup, and that a staffer ordered that Elord be punished for not following orders during dinner. In part because surveillance video was of poor quality, no one was charged in Elord’s killing.

“They took him alive and now they are giving me a corpse.” — Enoch Revolte, Elord’s father, to the Herald, on Sept. 4, 2015

[This story was originally published by the Miami Herald.]